Kulaman Limestone Burial Urns | “Kaban ng Lahi: Archaeological Treasures” and “Lumad Mindanao” Galleries at the National Museum of Anthropology Philippines

Featured Article: Kulaman Limestone Burial Urns, which were discovered in the caves and rockshelter sites of the Kulaman Plateau in South Cotabato, Mindanao.

The funerary practice of burying the dead in jars was a dominant custom in the Metal Age Period about 2,500 to 1,000 years ago in insular Southeast Asia.

Remains of jar burials are found throughout archaeological sites in Taiwan, Philippines, insular Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and central Vietnam. They vary across the region in terms of size, shape, and decoration but are typically earthenware, fashioned from fired clay. The burial jars from South Cotabato, however, are distinct because they are constituted of limestone carved into various sizes, shapes, and decorations, and used as secondary burial containers. A notable number of these limestone urns were discovered in the Caves of Kan-fenefe and Kan-nitong in the mountain range locally known as Menteng, located in the Kulaman Plateau, known to be inhabited by the Manobo and other ethnolinguistic groups.

Marcelino Maceda of the University of San Carlos (USC) in Cebu conducted the first formal research on the limestone burial jars in late 1962. Leading the team, they excavated two caves in a hamlet in Menteng, in the Municipality of Kalamansig in Sultan Kudarat (formerly part of South Cotabato). The second exploration in Kulaman Plateau was conducted in 1966 by Samuel Briones of Silliman University in Dumaguete, Negros Oriental. Briones discovered limestone jars and earthenware vessels in cave and rockshelter sites in Salangsang (still part of Kulaman Plateau but politically a village of the Municipality of Lebak). Soon after, Edward B. Kurjack of Miami University and Craig T. Sheldon of the University of Oregon did further research on the jars. They worked in cooperation with Silliman University and explored Salangsang in 1967 and 1968.

The jars are either round or squarish with vertical fluting or geometric patterns on the side. On average, the jars are about 60 cm tall and 25 cm wide. Jar lids vary in decoration from simple handles to elaborate gabled (roof-like) or conical forms, occasionally stylized with anthropomorphic (human form) or zoomorphic (animal form) elements.

According to Kurjack and Sheldon, the earliest urns are those with quadrilateral-shaped basal flanges and excised decorations, followed by urns with fluted decorations. The later urns are fluted quadrilateral in shape without basal flanges, followed by circular urns with fluted designs, then by urns with basal projections. The limestone jars were found along with pottery vessels, some stone adzes and flakes, and occasional ornaments made of shell, ivory, clay, iron, and stone. A collagen sample taken from the human bones directly associated with the limestone jars were carbon-dated to AD 585 +/- 85 years, or approximately 1,450 years Before Present (BP).

Scholars suggest that the tools ancient artisans used to carve the soft limestone include round- and flat-bladed chisels made of either stone or wood (bamboo). The technical skills and elaborate decorative repertoire observed in the limestone urns indicate superb craftsmanship and evident ingenuity among its makers during the mid-first millennium AD.

Jar burial customs have since been replaced by other mortuary practices towards the late first millennium AD, with funerary customs such as extended inhumations and coffin burials dominating the archaeological record in the late pre-colonial period from early to middle second millennium AD. Remarkably, the practice has been recorded as recently as the mid-twentieth century among the Sulod of Panay (also known as the Panay Bukidnon).

The limestone urns featured here are currently displayed at the “Kaban ng Lahi: Archaeological Treasures” and “Lumad Mindanao” galleries at the National Museum of Anthropology. Once the #NationalMuseumPH reopens its doors, we look forward to sharing with you these cultural treasures along with others that showcase the elaborate burial techniques and funerary customs practiced in different periods across the country. For now, however, #staysafe and #stayathome to help the country #BeatCOVID19.

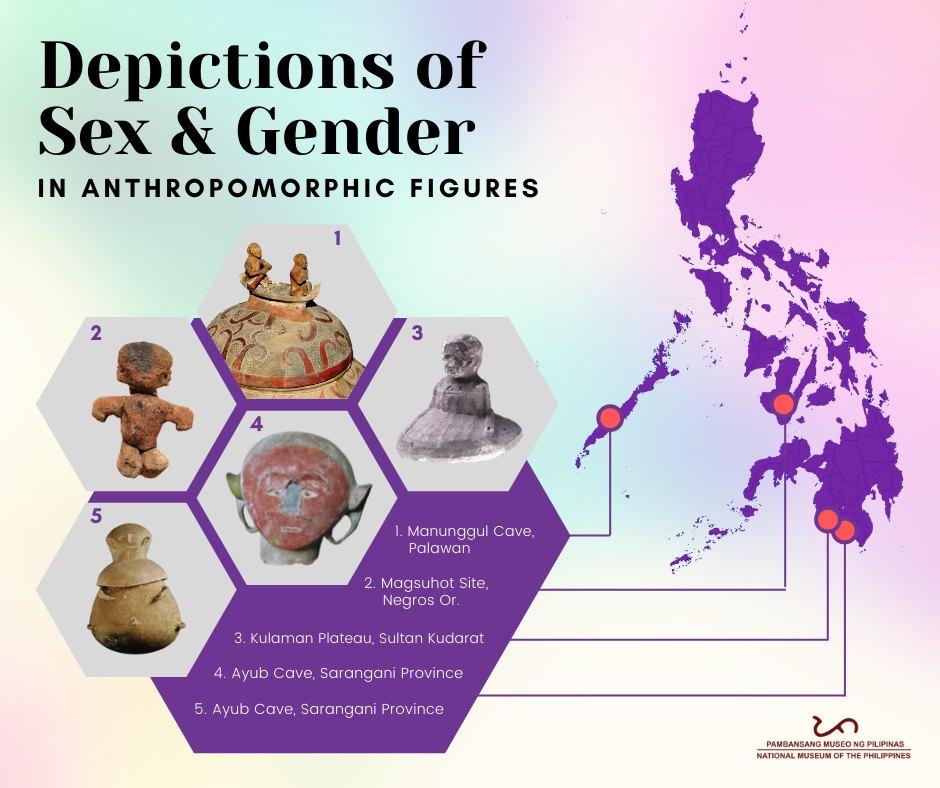

Gender in the context of Philippine Prehistory through featured Anthropomorphic Artifacts

Social scientists define gender as a socially constructed identity related to, but not determined by, biological aspects. While sex is defined as characteristics that are biologically determined.

Archaeological remains may be examined through various methods that seek to recognize how artifacts, structures, and burials may be associated with sex and gender distinctions and concepts of status, roles, and other similar aspects in the past.

|

| The Maitum Anthropomorphic Jar no. 21, which is a National Cultural Treasure, is depicted with male genitalia. |

In the Philippines, gender archaeology has yet to be fully explored and may be examined through materials from their mortuary context. One notable study of past identity construction focusing on artifacts was carried out by Museum Researcher Nida Cuevas in her investigation of sex and gender on the Maitum anthropomorphic burial jars. The human-like pottery from Maitum exhibits sex- and gender-specific traits in features such as genitalia, breasts, navels, and body ornamentation such as distending earlobes, bracelets, arm rings, and headbands. Her study classified the male and female breasts according to age (adolescent, young adult, and adult) in size and form. Furthermore, it also drew attention to depictions of gender portrayed by each age groups, notably indicating childhood, adulthood, and motherhood.

There are other anthropomorphic artifacts from Philippine archaeological sites that may, upon a closer study, potentially depict sex and gender but in general, evidence points to nonbinary distinctions. On the one hand, an earthenware pot from Magsuhot Site in Negros Oriental could symbolize two pregnant women with legs astride, interpreted as part of fertility rituals and the role of women in childrearing. Yet, the Manunggul Jar recovered in Manunggul Cave in Quezon, Palawan depicts two human-like figures on the lid sitting on a boat, representing a nongender-specific boat guide and the deceased, sailing into the afterlife. Moreover, this practice may be evident among limestone urns recovered at Seminoho Cave in Salaman-Lebak, Sultan Kudarat that also include carved lids depicting heads – sometimes whole upper body – that may be construed as portraits of individuals.

For further reading, please click here for a downloadable book on the Maitum artifacts: https://tinyurl.com/FacesFromMaitum

________________

Credits

Text and Images by Alexandra de Leon, Nida Cuevas and Sherina Aggarao, poster by NMP Archaeology Division

©️ National Museum of the Philippines (2021)

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?