Pasko sa Pilipinas: Symbols of Christmas and Traditions Unique in the Philippines + Interesting Trivia

The Christmas Season is the most awaited, celebrated, and longest event in the Philippines as it unofficially starts at the beginning of Ber-months or September 1st and ends during the Feast of the Holy Family in January the following year. Families start preparing and decorating for it is also a time for the yearly family reunions and gatherings.

Let's feature here the different symbols of Christmas and unique holiday traditions in the Philippines.

Parol or Philippine Christmas lantern

|

| Traditional Parol - Text and Poster by the Ethnology Division ©The National Museum of the Philippines |

The traditional Christmas lantern or parol (said to be derived from the Spanish word farol, meaning lantern) is the basic décor in every Filipino home during the holiday season. It has been around the country as early as 1800s and depicts symbolism of the Christian faith—the north star or Star of Bethlehem that guided the Three Kings who brought gifts to the newborn Jesus Christ.

During the Spanish colonization of the Philippines, Filipino farmers and fisherfolks were allowed to attend the nine-day pre-Christmas novena mass at dawn before going to the fields or the seas praying for a bountiful harvest and catch. Parol was originally intended to light the path of the attendees of the simbang gabi or Dawn Mass as there was no electricity then. Nowadays, parol symbolizes the Filipino Christmas spirit and can be found in homes of Filipinos (both in the Philippines and abroad), schools, workplaces, and other public places in the country and its presence signifies the beginning of a festive season.

The Filipino Christmas lantern is a traditional five-point star parol made of bamboo sticks and papel de japon or cellophane (a variation of which is a five-point star enclosed in a circle with two tails). The process of making one is not very complicated that it has been among grade schoolers’ Christmas project in schools.

The first step in making the parol is the assembling of the star’s frame using ten long bamboo sticks and five short sticks with length depending on the size and thickness of the parol one wishes to make (approximately 35 to 60 centimeters long and 12 centimeters thick), pakong bakya or nails often used in making wooden clogs, and strings or wires. The longer sticks are divided into two sets since the goal is to make the two faces of the parol with each star-shaped façade made of five long bamboo sticks assembled in an overlapping manner and tying the ends with string or wire. The two star-shaped façades of the parol are then tied together with the five shorter bamboo sticks propped and secured using pakong bakya along the five corners of the pentagon-shaped core. The shorter bamboo sticks provide support at the core of the structure, giving room for candle or light that can be placed inside the frame. A sufficient length of wire is twisted into a loop and attached to the topmost edge of the parol for hanging.

The next step is wrapping the star frame using papel de japon (tissue paper) or cellophane (plastic film). The preferred material is cut into specific shapes: five narrow diamonds to cover the sides and ten triangles to cover the five arms of the parol, leaving the pentagon-shaped center uncovered for the placement of a small candle or light (another variation is fully-covered parol with an electric bulb inside). The traditional adhesive used in securing the cutout pieces of papel de japon or cellophane is a paste made of cooked and thickened starch but other types of glues or adhesives may be used as well. The final step is the cutting and attaching of the tails. The lantern’s tails are also made of papel de japon that were folded into a narrow triangle and alternately cut halfway along the two long sides.

The Philippine parol has evolved continuously in terms of material, form, and design, as contemporary fashion and trends have warranted it. Besides bamboo sticks and Japanese paper, shells, electric lights, indigenous materials such as abaca, jute or rattan, and recyclable materials are now used in making modern-day parol. At present, the Philippine parol has become an inspiration for festivities or celebrations such as the Lantern Festival of Pampanga (the province being the lantern capital of the country) and the Lantern Parade of the University of the Philippines featuring huge lit lanterns and floats.

The parol, whether traditional or having a state-of-the-art design, became the most iconic symbol of Philippine Christmas.

Karoling or Pangangaroling

|

| Karoling or Pangangaroling local instrument made of bottle caps or tansan - Text and Photo by Ethnology Division © National Museum of the Philippines |

Pangangaroling is a traditional practice during the holidays wherein a group of children, family members, schoolmates, or an organization sings Christmas carols from house to house accompanied by or even without musical instruments. The said seasonal activity is one of the influences of Spain through the Roman Catholic Church considering the religious theme of classic Christmas songs, focusing on the birth of Jesus Christ in Bethlehem. In the Philippines, the home owner listens to the songs and greetings then gives something in return either in the form of money, candies, or other treats. This is one way of sharing your blessings during the season of giving.

Filipino children usually do the activity in the early evening beginning Misa de Gallo by singing a shortened version of “Namamasko (Sa May Bahay ang Aming Bati)” in tune with their hand-crafted percussion instruments such as the tansan tambourine, tambol, or marakas. These improvised musical instruments are made of upcycled materials that are available at home.

The tansan tambourine is made of metal bottle caps, flattened using a hammer or rounded stone and put together in a wire loop through drilled holes at the center of each flattened cap. This is accompanied by the tambol or drum, which may be made of a bamboo node, an empty milk can, or plastic gallon of condiments. To produce its sound, hands or with wooden sticks wrapped with rubber on one end are used.

The marakas are made of empty tin can as an improvised version of the coconut shell maracas and making one may require more work. Two small holes along the margins on one end of the can are made, along with a bigger hole at its center added for the wooden handles. Dried mongo seeds (mung beans) or pebbles inside are inserted before the handle is secured.

Adults also get involved with pangangaroling and are usually members of the church choir, barangay council, women’s club, or parent-teacher association. Unlike that of the children’s karoling that’s more random and for fun, the older ones give notice beforehand to specific households by distributing an envelope with a letter stating the schedule. To ensure support, the carolers mention the intended activities and outreach programs for which they are raising funds.

Pangangaroling is an essential part of Filipino Christmas and a reflection of Filipino values—sharing or giving despite the difficulties faced by many. Moreover, creativity is expressed through improvised musical instruments adding sounds to Filipino Christmas music that is enjoyed by many generations, bringing cheer despite the challenges of the outgoing year.

Related Article: Paskong Pandemic 2020 - Kahit Magkakalayo Sama Sama Ang Ating Puso - Pasko Sa Pilipinas

Did you know: Bohol's Daygon tradition

|

| The "Daygon sa Pagkatawo" (Praise for the birth), a community theater carol tradition, has almost disappeared in the island province of Bohol |

There is a cultural tradition inherited from the Spanish colonial era believed to have played a quiet role in fostering social unity, that has remained elusive in many parts of the country.

The "Daygon sa Pagkatawo" (Praise for the birth), a community theater carol tradition, has almost disappeared in the island province of Bohol, but apparently barely survives in Maribojoc, Antequera and Baclayon towns. It remains an endangered intangible cultural heritage.

Part of a series of devotional, quasi-religious activities leading up to Christmas, the intangible cultural heritage features dancing 'pastores' (shepherds), singing angels, haughty homeowners, and the Holy Couple being driven away and refused a space in several houses before finding a stable where the Christ child is born.

Handed down through a handwritten script, "Igue-igue: Daygon sa Pagkatawo" (Driven away: praise for the birth), it is a folk version of various events before and shortly after the birth of Jesus Christ based mainly on biblical accounts and some on oral tradition.

The origin of the Daygon tradition could be traced to the "posadas" (inn or shelter), an important Mexican Christmas tradition, features of which were undoubtedly brought to Philippine shores during the early 19th century Acapulco Manila China Galleon trade.

The Daygon or carol incorporates dance movements of shepherds, sore homeowners' antics, and lively tunes that make the otherwise drab singing of biblical stories and Catholic Church doctrines theatrical, attention-getting and entertaining.

"While these songs were (delivered) amid the dominant backdrop of Western colonization, there was no wholesale importation of tradition here," Bohol cultural historian Marianito Luspo said in an article. "Coming from the native peasantry, the daygons reflect an insistence at localizing or contextualizing the faith they received from a foreign source," he added. In his view, that makes the daygon "a valid expression of Filipino culture."

Daygon starts December 16 to 24, up to January 7. It is staged on the ground entrance of a patron or prominent leader's house-- complete with some basic moveable theater props. The participants, usually 20 to 30, wear costumes approximating the period of the Roman Empire.

After several "refusals" by the homeowners, the Holy Couple and the whole cast are invited to go up the house, and are served snacks.

The Daygon lyrics bring the Christian message of salvation:

"Ang pulong sa anghel sabton ta kay ang dakong kalipay midangat na, kay natawo tungod kanimo ang manluluwas nga Ginoo." (Listen to the angels' message that brings great joy since the Savior is born for you).

A study in 2018 observed that while the original Daygon worked as a devotional, cultural expression of faith, it also brought the villagers and their patron-leaders together in a spirit of giving. It served as a mechanism for togetherness or social cohesion in some parts of Bohol.

Bohol's Daygon tradition could be considered part of a distinct intangible cultural expression of the coastal ecological zone of central Visayas.

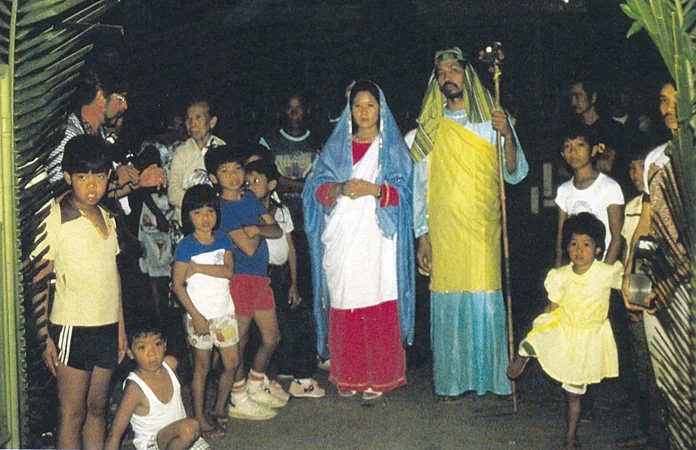

Panunuluyan

|

| A couple dressed as Mary and Joseph searching for an inn in the panunuluyan, Hagonoy, Bulacan, circa 1981 (Nicanor G. Tiongson) |

The panunuluyan —literally, “requesting to come in” in Tagalog—is a Christmas procession that dramatizes the search for an inn by Mary and Joseph on Christmas Eve in Bethlehem. It is also known as panawagan or “calling out” in Tagalog; kagharong or panharong-harong or “going from house to house” in Bikol; or maytinis, from Latin matines, or early morning prayers, in Cavite Tagalog.

The panunuluyan may have descended from the Mexican posadas but differs from the latter in that the posadas are usually performed for nine consecutive nights, while the panunuluyan is done only on Christmas Eve. The custom was probably introduced into the Tagalog and Bicol towns by Mexican or formerly Mexico-based priests or sailors who came to the Philippines on the galleons and settled in towns near shipyards or dockyards.

This procession usually features two karo or floats, bearing the images of San Jose and the Virgin, accompanied by one male and one female singer and a brass band. At about eight on Christmas Eve, the procession leaves the church and goes to about three or more houses located in different parts of the barrio or town. At each house, the procession stops. The male and female singers, representing the Holy Couple, sing, to the accompaniment of the band, a mournful plea to the may bahay (houseowners), begging them for a room for the night for Mary who is about to give birth.

There are many variations of the panunuluyan. In some towns, the singers are themselves dressed in costumes like those of the images in the karo; in others, the singers are in everyday clothes; in others, there are no images, only costumed singers. Sometimes, and this is probably the older tradition, the verses are not sung but partly or wholly declaimed. The accompaniment too may vary, from a single guitar to a 10-piece band/orchestra.

By far the most elaborate of all panunuluyan is the maytinis of Kawit, Cavite, where a young couple costumed as the Virgin and San Jose ride a huge float, which in turn is accompanied by about 13 other floats depicting characters and scenes from the Old Testament, like Adam and Eve, Moses, King David, Queen Esther, Judith and Holofernes, Samson and Delilah; the New Testament, like the Annunciation, the Immaculate Conception, and the Visitation; and Kawit’s past (Mother Country and Independence). Before midnight, the Holy Couple come down from their float, walk to the church, and ascend the stairs to an elaborate Bethlehem scene on the altar, where they are welcomed by “angels” in white costumes and led into a “cave” where they disappear behind the curtains. At the “Gloria,” the curtains of the “cave” are drawn, revealing the Nativity scene, with the images of Mary and Joseph wearing the costumes of their live counterparts. Wooden angels descend from the “heavens” and several angelita (girls dressed as angels) adore the Christ Child as the drums and orchestra play the jubilant “Gloria.”

Because of its popularity, the form of the panunuluyan has been used by different groups to reinterpret the search for an inn by Mary and Joseph according to sectoral realities. A play inspired by the panunuluyan is the Philippine Educational Theater Association’s Ang Panunuluyan ng Birhen Maria at San Jose sa Cubao, Ayala, Plaza Miranda, Atbp. Lugar sa Loob at Labas ng Metro Manila (Virgin Mary and Saint Joseph’s Search for an Inn in Cubao, Ayala, Plaza Miranda, and Other Places Inside and Outside Metro Manila),1979. Here the images of Mary and Joseph come to life, and down from their float and are led by a young boy, Jesus, to different parts of Metro Manila to see for themselves the conditions of Philippine society. They go to Carriedo, Quiapo, where the vendors eke out a living; to the Manila Hotel where the rich are enjoying themselves, oblivious of the poor; to Navotas, Rizal, where the batilyo or fish stevedores are overworked and underpaid; to a farm where peasants are deprived of their rightful share of the harvest by the landlord; and to California Clark Philippines where workers are forming a union to fight for better wages. In the end Mary and Joseph realize that their plight as working people is no different from that of the sectors they visited.

During the incumbency of Lou Veloso as Manila City councilor, from 1995 to 2012, Tanghalang Santa Ana presented the panunuluyan. The group performed the panunuluyan for nine evenings, starting December 16. The group coordinated with the barangay officials to identify the most impoverished family in each of the nine barangays of Santa Ana. The residence of each of these families became the performance site of the panunuluyan. The dramatization culminated on the eve of Christmas inside the Santa Ana Church.

Other panunuluyan have been organized by cause-oriented groups, like those of the urban poor, the workers, the teachers, and the students, using images or puppets to represent the Holy Couple who go to several destinations in Metro Manila, in a procession that is a convoy of jeepneys and trucks. An example was that organized by Buklod in December 1991 in the quadrangle of the Claret Church in Quezon City.

Pastores

|

| Women and men dressed as pastores or shepherds singing and dancing to villancico music, Camalig, Albay, 1989 (CCP Collections) |

The pastores, from Spanish pastores meaning “shepherds,” is a dramatization of the shepherds’s adoration of the Infant Jesus in Bethlehem, usually presented in the days just before Christmas or on Christmas Eve; it can also refer to a band of singers dressed as shepherds who perform Christmas songs and dances from house to house during the Christmas season.

Far north in Cagayan, there is the infantes, which is the locality’s equivalent for the pastores.The girls dress like baby dolls and click bamboo castanets, while the boys beat on bamboo tubes called tubtubong. The Three Kings are represented as simulated higante (giants), while accompanying angels are teased by a comic who represents the devil.

In Bicol, the pastores are 12 adults or children, mostly female, led by a capitana (female captain). The number probably alludes to the apostles with the capitanarepresenting Christ. The “shepherdesses” wear full skirts, round-necked blouses with puffed sleeves, and wide-brimmed hats, while the “shepherds” sport long-sleeved shirts, breast and waistbands, and decorated hats. Groups dress in a uniform color—red, blue, or green. At every house, they sing, to the accompaniment of a small orchestra (guitar, violin, bass, drum), a series of Spanish villancicos or carols (including “Pastores a Belen,” which is attributed to Jose Rizal), as well as Bikol carols, while executing dance movements and patterns, using handkerchiefs and rattan arko or arches gaily trimmed with colorful paper as props. They are gifted with money or food by the owners of houses at which they sing. To encourage the barrio people to continue with the tradition, pastores contests are held on stage in Legazpi, Albay, during the Christmas season.

Most colorful in Bicol is pastores Talisay in Camarines Norte. Looking colorfully Mexican, it has women swirling their voluminous poblana skirts like cascading rainbows, while the men bear papier-mâché horses to signify that they are riding up and down hills. With kaleidoscopic movements, the women also carry arches of flowers. Another in Pilar, Sorsogon, is pastores Santo Niño, where boys dress in Middle Eastern shepherds’ garb (long white soutanes and head scarves with headband), the girls in white or pastel dresses, usually wearing hats with ribbons or flowers. They dance to “Vamos a Belen”played by a rondalla and a drum. Still another is pastores Tubog in Oas, Albay, where again shepherds dress in the Middle Eastern way, with children carrying lambs (made of bamboo and rice paper) as piñatas and floral arches. Six pairs of girls and boys are led by a capitana. Characteristically, they wear abaca slippers with simulated cloth leggings and sing in Spanish, Latin, and Bikol. This is done on the feast of the Three Kings. Pastores Bungiawon is also attributed to Oas in Albay. Here, the girls put ruffles of recycled plastic bags around their skirts and arches. In Mercedes, Eastern Samar, skirts are made of crepe paper, and blouses from commercial plastic sacks.

In her masteral thesis in the University of the Philippines, Jiye A. Margate describes the pastoras from Camarines Sur. In the pastora Baao and pastora Bombon, girls wear the usual pretty dresses and hats and sing to different musical accompaniments: in Baao, originally to the violin, double bass, and guitar, but now only to the saxophone; and in Bombon, originally to saxophone, violin, guitar, and flute, but now more often just to a guitar. Here girls train under their elders and danceas panata (vow) to the Virgin Mary.

In Cebu and Leyte, the pastores, played by a group of children wearing hats with bands, sing and dance at different houses, confront and drive away the devil, who dissuades them from visiting the Messiah, and then proceed on their journey to adore the child. Sometimes a couple playing Mary and Joseph presents them with the image of the Christ Child at some point in the journey.

Out in Cebu is pastores Kalawit in one of the Camotes Islands, where middle-aged women dance as their fellow fisherfolk watch them. In the nacio pastores of New Washington, Aklan, the ritualists dance with the image of the Niño dormido (asleep) and sing old villancicos. In Ibajay, Aklan, the bailo (from baile) de pastores features boys and girls dressed in white with red waistbands and hats with flowers and carrying tambourines while dancing. In Leyte, pastores Tolosa has singing in Waray, with a comic encounter between the devil and the shepherds. Also in Ormoc, Leyte, a little more complex scenario shows a half-man and half-monkey devil trying to mislead the shepherds until the latter are rescued by an angel.

Most of these pastores with place-names are from the field research of National Artist Ramon Arevalo Obusan. These names serve as index to the repertoire of the Ramon A. Obusan Folkloric Group. For several years, Obusan presented the program Vamos at Belen every December at the Cultural Center of the Philippines.

Simbang gabi

|

| Simbang Gabi - Text and poster by Ethnology Division © National Museum of the Philippines |

Simbang gabi or dawn mass is a nine-day devotional prayer prior to Christmas day starting from December 16 to December 24. It is also called novena mass, from Latin novem, or nine. Also referred to as Misa de Gallo or rooster’s mass, its reference come from the ritual being celebrated at dawn with the crowing of roosters at around four in the morning. In some places, Misa de Gallo specifically refers to the culminating night mass on December 24th or Christmas Eve. It is also known as Misa de Aguinaldo or “gift mass,” emphasizing the faithful’s sacrifice of waking up early morning to attend the mass as an expression of gratitude for the birth of the Savior—Jesus Christ.

Brought by the Spanish religious missionaries to the Philippines during the colonial period, simbang gabi was traditionally observed in honor of the Blessed Virgin Mary. According to Pope Sixtus V, it is also for the glorification of the Roman Catholic Church, spreading of the Catholic faith, and preservation of newly baptized locals. Today, it is celebrated for the perseverance of the Filipino faithful and the preservation of religious practice in the country.

Simbang gabi in the Philippines was customarily conducted at night instead of dawn. However, the clergymen noticed the struggle of locals attending the mass, having toiled during the day, particularly the farmers and fishers. Shifting to daybreak, priests directed church bells to ring at dawn in time for masses to be held, consequently bestowing blessings for the day’s good harvest or productive catch. At present, some churches also offer anticipated mass instead of the dawn mass.

Most Catholics believe that their fervent wishes would be granted upon completion of the novena mass. In some parishes, select families sponsor the simbang gabi as a form of their devotion or panata. This usually involve donation of funds to support a particular project or program of the parish. Before the start of the mass, members of the sponsoring family are asked to read a short prayer and light a lantern or sometimes place one figure or character in the nativity scene until completed on Christmas Eve.

During simbang gabi, it is common to see the area surrounding the church lined with food stalls of local delicacies. Topping the season’s menu are different types of kakanin (rice cakes) such as puto bumbong, bibingka, puto, and suman served with hot salabat (ginger tea) and hot tsokolate (cocoa).

There’s also an option of having steaming hot porridge (lugaw and goto) and soup (sopas) instead of kakanin.

Also Read: 10 Crimes Against Christmas That Filipinos Tend to Commit

Noche Buena

|

| Tupig, bibingka at Puto Bumbong for Noche Buena - Text and poster by the NMP Ethnology Division © National Museum of the Philippines |

Christmas is indeed one of the most celebrated seasons in the Philippines as we spend a considerable amount of time and resources in decorating our homes and offices; in buying gifts for our family, friends and inaanak (godchildren); in sacrificing by attending the novena (nine-day) Mass simbang gabi; in visiting our relatives, neighbors and schoolmates through pangangaroling; and in planning for the Noche Buena.

|

| Paskong Pinoy: Karaniwang handa ng mga Pilipino sa Noche Buena |

The traditional Christmas Eve feast is referred to as “Noche Buena”,Spanish for “night of goodness.” After attending the Christmas midnight Mass, families gather together in one house and they would usually bring their signature dish, dessert or beverage to share in the feast. This is also considered as the annual family reunion revolving around food, music, and gift-giving. Young children line up for the customary pagmamano, an honoring gesture of bowing and then pressing the elders’ hand on the forehead before they are given gifts.

Back in the 16th century, Spanish friars required those who attended the midnight Mass of 24 December to fast until Christmas morning, 25 December. Since after midnight is technically considered the morning of the next day, the locals started to gather together after the Mass and partake of the prepared feast.

The special menu for Noche Buena is of Spanish influence such as lechon, hamon, embutido, morcon, chicken relleno and quezo de bola. The distinctly traditional Filipino food prepared and served are kakanin (rice cakes) such as bibingka, puto bumbong, tupig, and tinubong paired with hot cocoa drink, coffee, or salabat (ginger tea). These rice cakes are offered to the gods at the end of the year as thanksgiving and shared with relatives and neighbors as part of the season of sharing.

As we gather and partake of the feast during the Noche Buena, may we be reminded to celebrate safely with our families living in the same household, to wash our hands, wear masks and to prepare healthy food, contributing to our wellbeing and protection from #COVID19.

Kahit na Pandemic: Paskong Pinoy: Spectacular Giant Christmas Tree in Manila - Tuloy Na Tuloy Pa Rin Ang Pasko

Did You Know?

Christmas is just a couple of days away! Aside from Simbang Gabi and other traditional ways of marking the season, most Filipinos celebrate the holidays with the traditional Noche Buena Feast on Christmas Eve, consisting of food especially prepared or those we equate with luxury, such as queso de bola and ham.

Indeed, the Yuletide Season will not be the same without the fiesta fare. Even during this pandemic, Filipinos still look forward to enjoying their Christmas dinners and being reunited with their families and friends. Whether you will serve conventional food or imported delicacies this Christmas, beware of the dangers those may pose, besides being careful with getting infection with COVID-19.

Did you know that you can get parasites just by eating raw or undercooked food?

Let us reintroduce you to some of our favorite seafoods:

|

| Hipon |

|

| Kuhol |

|

| Talangka |

Food-borne parasitic diseases documented in the Philippines include echinostomosis, heterophyidiosis, chlonorchiosis, paragonimiasis and capillariosis, to name a few. Since consuming partially cooked or raw "kilawin" fish, crustaceans and snails are considered part of Filipino dishes, there are reports that those diseases continue to exist in the country.

In order to avoid catching these particular diseases, make sure to prepare and cook your Noche Buena food well!

Iba't-ibang Kakanin or Rice Cake

|

| Kakanin |

A known source of carbohydrates, kakanin - derived from the words “kain” (to eat) and “kanin” (rice) - is a common breakfast or snack in the Philippines made from ground or whole grain rice. It is also prepared during important occasions such as birthdays, weddings, town fiestas, funerals, and other ceremonial rituals. Oftentimes, kakanin is given as pasalubong or gift by someone arriving from a trip. In some rural areas, rice cake preparation for weddings and feasts traditionally involves collaborative work among family members, kin groups and neighbors.

Most rice cakes are made of whole grains of malagkit (glutinous rice) which are sometimes ground into fine powder to make galapong (rice flour) using a gilingan (grinder). Sometimes these are pounded using a mortar (lusong or luhung) and pestle (referred to invariably as halo, hulo, a’lo, lalu, lal-e or bokbokan). Before commercial rice milling technology became available, harvested rice grains are threshed manually using huge wooden mortar, baskets, animal hide and wooden pestle or feet to separate the grain from the stalk. Atcha (sieve) made of bamboo is used for straining grains from stalk by the Itawes of Cagayan and other agricultural communities in northeastern Luzon. The collected grains are sun-dried before pounding using mortar and pestle to remove the husks. The pounded grains are transferred to a bilao or nigo (winnowing tray) made of bamboo and rattan to further remove the chaff. Mortar and pestle also turn the grains into fine powder and the fine powder is mixed with coconut milk or cream and molasses or sugar on the bilao or other shallow baskets. Today, winnowing trays are also utilized as containers of rice cakes peddled on carts or of vegetables in the market. Among the groups in the Cordillera, pounding and winnowing of rice are usually done by women for everyday consumption, but for ceremonies or special gatherings, both men and women help in the preparations.

Aside from rice, coconut meat and/or milk is one of the basic ingredient of kakanin. The coconut meat grater or shredder (referred to as kudkuran, kaguran or chikudkuran) is traditionally used for manually scraping the flesh of a mature coconut from its shell. The shredded coconut yields the kakang gata (first pressed cream) and gata (coconut milk) by adding lukewarm water and squeezing its juice. Fresh shredded coconut meat may also be added as toppings of puto, kutsinta and palitaw while latik (coconut curds, caramel or jam) and coconut oil are mixed and topped on suman and bibingka.

The popular suman (or ibus or budbud) is a type of steamed rice cake cooked in coconut milk, salt and sugar then wrapped in fresh banana, palm or pandan leaves in varying shapes, sizes, and weaving techniques across the country. In some parts of southern Luzon in the provinces of Batangas and Mindoro, suman and kalamay (made of galapong, gata and brown sugar) play an important role in traditional wedding ceremonies as dulot, which are gifts given by the bride and groom to their godparents before the wedding. During the wedding party, the newlyweds are given a plate of bite-sized kalamay as its sticky quality is believed to make them stick or stay with each other.

Another variety of rice cakes similar to suman is the morón in the Eastern Visayas. It is also prepared using glutinous rice, coconut milk and sugar then wrapped and cooked into a cylindrical form in banana leaves but with an additional ingredient of tablea or cocoa powder. In northwestern Luzon provinces, they have tupig, which is usually made from galapong, coconut milk, muscovado sugar, strips of young coconut meat or toasted sesame seeds, wrapped in banana leaves before roasting it over charcoal. A favorite dessert or snack from Surigao in northeastern Mindanao is the cone shaped, soft textured delicacy called sayongsong made of glutinous rice, sugar, calamansi juice, roasted peanut and coconut milk wrapped in banana leaf. Aside from fresh leaves, other Filipino rice cakes are cooked in bamboo tubes such as sinabalo (Cagayan), binungey (Pangasinan), tinubong (Ilocos), linutlot or lutlot (Palawan) and the popular Christmas season treat puto bumbong.

There are rice cakes especially prepared as part of ceremonial offerings to the deities such as the bakle in Kiangan, Ifugao during their post-harvest thanksgiving festival for bountiful harvest called Bakle Festival and the tinuom and ulupi in Panay Island during a post-farm clearing and chanting ritual of apology to the spirits called the sagda ceremony. In the Mayohan Festival in Tayabas, Quezon, locals and visitors anticipate the hagisan ng suman or tossing of rice cakes wrapped especially in coconut leaves as a form of thanksgiving to their patron saint San Isidro Labrador for the abundance of harvest and for the blessings they received. The Suman Festival is also celebrated in Baler, Aurora every February showcasing the sweet sticky rice cakes which decorate the streets and houses during the festivity.

Additional Trivia

How many times have you listened to a classic Christmas song lyric with the word “mistletoe” in it? #Mistletoe is an iconic plant of the festive season that can be found in a wide range of habitats from closed humid forests to arid woodlands.

|

| Actual photo of some of endemic mistletoes in the Philippines |

In fact, you can also kiss your loved ones under the mistletoe here in the Philippines!

Can you believe that we have 12 genera of mistletoe in the country? Here’s a list of our very own mistletoes https://www.philippineplants.org/Families/Loranthaceae.html

|

| Actual photo of some of endemic mistletoes in the Philippines |

Amyema is the most diverse genus of the Mistletoe family with 24 species and 19 of which are only found in the country. The genus name was derived from two Greek words “without” and “to construct”; because there was no information available on the plant prior to its discovery. Mistletoes are parasitic shrubs that draw part of its nourishment from the host tree they grow on. Its fruits are edible for birds specifically sunbirds and flowerpeckers which contribute to its seed dispersal and pollination.

|

| Actual photo of some of endemic mistletoes in the Philippines |

This previously unrecognized plant is now considered as one of the holiday-famous plants that are known to have bright flower colors well-suited in the observance of the holidays.

Tatlong Hari

|

| Tatlong hari in Gasan, Marinduque, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

Tatlong hari —literally, “Three Kings” in Tagalog—is a Christmastide custom centering on the Three Magi who, according to tradition, traveled from the East to adore the Infant Jesus in Bethlehem.

In towns like Floridablanca, Pampanga, three adult males in royal costumes attend the Epiphany mass and walk with the procession of the Virgin through the streets.

In Cavinti, Laguna, three boys in crowns and capes attend mass, then ride on horses followed by beautiful sagala (young ladies) carrying images of the Three Kings. The group heads for the town hall, goes up the stairs, and from the balcony showers the crowds below with candies and coins.

In Gasan, Marinduque, on the first Sunday of January, the play of the Three Kings begins after the morning mass with a parade featuring Herod, Herodias, Herod’s soldiers, a pair of angels, and a male and female higante (giant figures made of bamboo and cloth that are carried by persons underneath) and the Three Kings riding on their horses, following a man carrying a parol (star lantern) hoisted on a long pole. The parade ends in front of a stage with a set representing Herod’s palace. The play begins with the kings going up the stage to talk to Herod, who welcomes them but cannot tell them where the Messiah has been born. The Kings go down the stage, walk around the little square and end up adoring the image of the Infant Jesus, enthroned on an altar in one corner of the patio and guarded by angels and the higante couple. Tired of waiting, Herod sends his soldiers after the kings but the soldiers come back empty-handed. In anger, Herod orders the massacre of all baby boys below two years of age and ends the play with mad laughter.

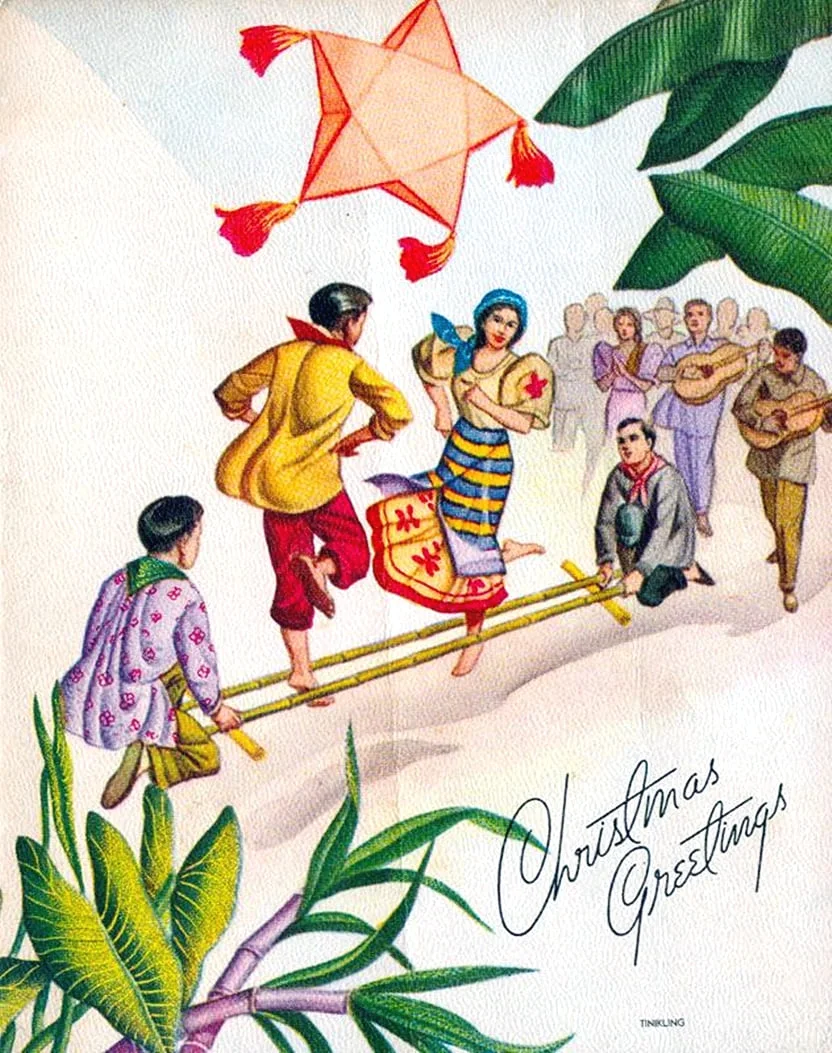

Villancico

In its original meaning, the villancico is a Spanish musico-poetic song form consisting of coplas (stanzas) linked by an estribillo (refrain). The term was taken from the word “villano” (rustic) and, though simple in music texture, it was cultivated into a complex secular polyphonic music during the late 15th century and the 16th century. Beginning the 17th century, texture became simple again or monophonic, and the use of devotional and religious themes gained importance. From its secular constitution, villancicos (also referred to as letra or tono) became a genre of monophonic sacred songs with popular elements that were sung in Spanish or in the vernacular. It was this style that was heard in church services in Spain and its colonies, particularly during liturgical feast days such as Christmas, Ascension, Epiphany, and Corpus Christi. There was a rapid decline in its popularity from the 18th to the 19th century, but it continued to be widely cultivated in Latin America and in the Philippines. Although religious in function, the villancico continued to exhibit predominant secular and popular elements. Due to its extensive utilization during Christmas, by the mid-19th century, the term villancico was used to refer to Christmas songs. Since then, this has been the generally accepted meaning of the term.

The earliest existing music source of villancicos in the Philippines probably dates from the second half of the 17th century. This source has been preserved in the Dominican church of San Juan del Monte, and one in the collection stands out because it is in the vernacular, titled “Letra en Tagalo[g]” (Lyrics in Tagalog). This source was followed by another set, probably composed in the 18th century, found in the five-volume anthology of sacred music Manual-Cantoral de Santa Clara published in the early 1870s. Included in volume four of a multivolume anthology was a set of four villancicos al santisimo (songs to the Most Holy) performed during the feast of the Corpus Christi, a villancico al santisimo for Holy Thursday, and a set of four villancicos for Christmas—namely, “El Rey de los Cielos” (The King of Heaven), “Ea Pastores” (Come, Shepherds), “O Grande Mysterio” (Grand Mystery), and “Venid Gentes Todas” (Come All Peoples).

|

| Pastores performers in Bicol, circa 1990 (Photo from CCP Collections) |

Villancicos became songs for Mass Proper (entrance, offertory, communion, and so on) in the Misa de Aguinaldo (nine-day dawn Masses), which starts on 16 December to honor the Virgin. It is also sung in the Misa de Gallo (midnight Mass) on Christmas Eve, together with the Mass Ordinary (Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, and so on)—that is, the Misa Pastorela. There are historical accounts that mention of Spanish friar musicians assigned in the Philippines who composed villancicos. Among them were Fray Lorenzo Castello (1686-1743), an Augustinian from Valencia, Spain, assigned to the San Agustin Church in Intramuros, Manila, who composed two volumes of villancicos as well as arias, and Juan Bolivar (1708-1754), an Augustinian friar renowned for his exquisite singing ability who was known to have composed polyphonic villancicos and settings of the Gloria and Credo in the 18th century.

Because of the genre’s widespread usage through the annual Christmas season for over three hundred years, traditional Spanish villancicos are quite popular across the islands. The “Pastores a Belen” (Shepherds at the Nativity) and “Nacio Nacio Pastores: Villancicos de Navidad” (Rise, Rise Shepherds: Songs of the Nativity) are popular among the populace, even until now. These compositions are included in the Department of Tourism publication titled Villancicos: Mga Awiting Pamasko (Villancicos: Christmas Hymns), 1971, compiled and edited by Rosalina Abejo, RVM, 1922-1991.

Aside from the villancico performed during the Christmas Masses, villancico was also practiced in related cultural devotional practices, such as the pastores, the panunuluyan in Tagalog-speaking areas, and the suroy in Bohol, which are all extra-liturgical folk Christmas traditions. The Bikol pastores is a musical reenactment of the nativity story where singers, wearing colorful costumes accompanied by musikeros (musicians), dance and sing to the villancico tune “Pastores a Belen.” The panunuluyan is a Philippine Christmas dramatization done through a song of Joseph and Mary’s search for lodging on the night of Jesus’s birth. This could have originated from the Mexican nine-day posadas, but the panunuluyan is done only for a day. Lastly, suroy in Bohol means “to go around.” It is a unique tradition of caroling in the town of Loboc held for a total of 40 days. It starts on 24 December and culminates on 2 February. This is participated in by cantores and cantoras (male and female singers, respectively), and band musicians, as well as children. They go to different barangays every day to give Christmas cheer through the singing of villancicos and other songs. Vernacular villancicos, such as the daygon (Visayan Christmas songs), are strong evidence that the villancico tradition has been significantly entrenched in the social life of the people.

|

| Cebuano elders performing the daygon, 1991 (Photo from CCP Collections) |

The villancico also paved the way for musicians in the islands to compose in the genre. Remigio Calahorra (1833-1990), a Spanish peninsular professor of the Colegio de Niños Tiples of the Manila Cathedral, wrote a villancico that has survived and is now part of the archive collection of the UST Benavides Library. Although rhythm and meter are not the distinguishing features of the genre as seen in the 17th and 18th century examples, composed villancicos in the Philippines beginning in the 19th century utilized rhythmic patterns that are a distinctive feature of Misa Pastorela music. Composed villancicos from this period also manifest the use of insistent dotted rhythmic patterns in 6/8 time, as evident in the Calahorra villancico. Other trained Filipino musicians followed suit. Marcelo Adonay (1848-1928), considered the most prominent Filipino church musician of the late 19th century, elaborately composed a villancico titled “A Belen Pastores,” complete with orchestral accompaniment.

By the turn of the 20th century, Filipino musicians trained in the conservatory composed in the genre. By this time, the genre was already codified with the following musical style characteristics: (1) a predilection in the use of 6/8 meter and occasional use of duple meter, (2) extensive use of the distinguishing dotted eighth notes and pastorela rhythm, (3) employment of tra la la la syllables, and (4) utilization of the two-part song form (copla and estribillo). Francisco Santiago (1889-1947) wrote “Philippine Christmas Carol,” a medley of Christmas songs that exhibits the said villancico characteristics. Another composition titled “Gloria de Dios (Villancico Filipino)” (Glory of God) by Antonio Molina (1894-1980), found in the Filipiniana collection of the University of the Philippines Music Library, demonstrates an attempt to recognize the villancico as an appropriated Filipino tradition. The music exhibits clear villancico stylistic features, with text adapted from Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s famous poem “Christmas Bells.” Tagalog, Spanish, and English lyrics were incorporated into the notated music. Another noted composer of the Filipino villancico is Felipe de Leon Sr (1912-1992), who wrote “Payapang Daigdig” (Peaceful World). This piece is unusual because it is a solemn and melancholic Christmas carol. It was the arrangement of Lucio San Pedro (who deliberately omitted the second part) that changed its tone—a closer scrutiny of the original composition, particularly of the second part, shows that de Leon did utilize the distinguishing Filipino villancico rhythm. De Leon also composed “Noche Buena” (Christmas Eve Feast) and “Pasko na Naman” (It’s Christmas Once Again). In the anthology of villancico she herself edited, Rosalina Abejo composed a piece titled “Villancico Filipino.” Lucio San Pedro’s most important contribution in this genre was making good choir arrangements of Filipino-composed villancicos. He arranged “Diwa ng Ating Pasko” (Our Christmas Spirit) by Ramon Tapales and did a Christmas medley titled “Mga Awiting Pasko” (Christmas Hymns), which culminates in the original Cebuano but has been translated to Tagalog and is more popularly known as “Ang Pasko ay Sumapit” (Christmas Has Come).

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?