The Bugkalot Tribe of the Philippines: History, Culture & Art, Language, Customs and Tradition [Philippine Indigenous People | Ethnic Group]

The Bugkalot appear in most ethnographic studies as “Ilongot,” and thus are generally called such by outsiders. However, Bugkalot, also spelled Bugkalut, is what they call themselves. The etymology of the term is unknown, but Irungot, which is another self-designation, means “from the forest.” “Ilongot” or “Ilungot” comes from the prefix i, denoting “people,” and gongot or longot, “forest”; thus, the word means “people of the forest.” Ngot or ngut also suggests fierceness. A Spanish version is “Egongot.” “Ilongot” has come to connote such negative images as “savage,” “treacherous,” and “ferocious,” largely as a result of Spanish and American colonialist bias. However, at least two people’s organizations in Quirino carry the name “Ilongot.”

Lowland converts, particularly the Isinay, refer to the Bugkalot as Ibilao or Ivilao. Other terms refer to Ilongot subgroups: “Abaka” refers to the Conwap river settlers, “Italon,” to the northern waters of Cagayan river settlers, and “Igongut,” to the Tabayon river settlers.

Although there is a large concentration of villages at the source of the Cagayan River, Bugkalot communities are generally scattered in the southern Sierra Madre and Caraballo mountains. Numerous rivers and dense tropical rainforests define Bugkalot territory, covering the provinces of Aurora (particularly the municipality of Maria Aurora), Nueva Vizcaya (Kasibu, Dupax del Norte, Dupax del Sur, and Alfonso Castañeda municipalities), Quirino (Nagtipunan municipality), and parts of Nueva Ecija. The Bugkalot population during the Spanish colonial period was estimated at 5,000. The 1903 census during the American occupation reported 3,601. This number had at least doubled 30 years later, when a 1939 census reported 7,042 Bugkalot living in Nueva Vizcaya and southern Isabela. War and disease in the 1940s caused the population to decrease to 5,282 by 1946.

In 1993, the Bugkalot population was reported to be at around 18,000, although the number may have been bloated in order to prevent Bugkalot displacement mainly due to government infrastructure projects in their territory. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), in consultation with a Bugkalot chief, reported an estimate of 16,000. In the 2000 government census, the combined population of the Bugkalot and Ilongot in the provinces of Nueva Vizcaya and Quirino was 6,668, broken down as follows: 1,180 or 0.3% of the total population of Nueva Vizcaya; and 5,488, or 16.46% of that of Quirino province. The same census did not provide the Bugkalot population in Aurora and Nueva Ecija.

The Bugkalot language, also known as Ilongot, Bugkalut, Bukalot, and Lingotes, is spoken by more than 50,000 people, mostly in Quirino province, eastern Nueva Vizcaya province, south Isabela province, and around the northern part of the Cagayan River. The language (Bugkalot Dialect) can vary in words, grammar, intonation, and speed of delivery. For example, in the Bua River area, the plural is achieved by prefixing the numerals or the word adulang (many); the possessive by suffixing -co (first person), -mo (second person), and -da (third person) to the noun; and the gender by adding -a becog (female) or -a gaki (male) to the noun.

The Bugkalot numeral system has been described as “quinary” instead of the more common decimal. Cardinal numbers are siyet (one), dua (two), tego (three), apat (four), and tambiang (five). Succeeding numbers are each represented by tambiang and the respective additional number, thus: tambiang no siyet for six, tambiang no dua for seven, and so on. The number 10, which is tampoo, is a combination of tambiang and pulo, the latter being a common Philippine marker for 10.

History of the Bugkalot Tribe in the Philippines

Spanish colonization barely penetrated the Bugkalot domain. Instead some natives were lured to the lowland missions. These converts, like the Bugkalot of Baler, were exempted from tribute. Protected by mountains and forests, most Bugkalot were able to repel foreign intrusions. In 1591 and 1592, a number of Spaniards were killed by the Bugkalot in the expeditions led by Don Luis Perez Dasmariñas. Hence, Spanish policy on the Bugkalot became belligerent; nonetheless, all their subsequent punitive expeditions failed. At times different ethnolinguistic groups united against the common foreign enemy. The Isinay town of Burubur in southern Nueva Vizcaya was liberated by the combined Isinay-Gaddang-Bugkalot forces soon after it was occupied by the Spaniards in the early 1700s. The same cannot be said about the Gaddang and Isinay who were residing in the plains of Magat River Valley. Eventually, the Gaddang of Bayombong and the Isinay of Buhay, the present-day Aritao, capitulated to the Spaniards, submitted to conversion, and were used as soldiers or transporters of supplies in Spanish expeditions against the Bugkalot.

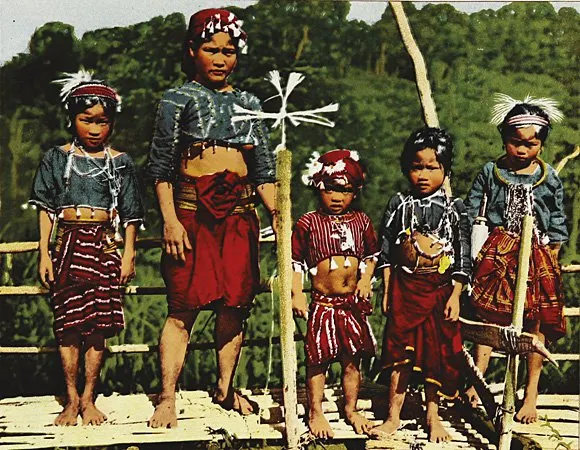

|

| Bugkalot woman and girls, 1913 (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Several Dominican missions in Bugkalot domains were undertaken by the Spaniards in the 1740s and 1750s. Protected by soldiers from the Ajanas fort in Aritao and Christianized peoples in Nueva Vizcaya, the missions were led by Father Juan Cruz in 1746, Father Francisco Pallas in 1748, and a Father Bordallo in 1754. These missions, which were accompanied by military raids, were repelled by fierce counteroffensives mounted by the Bugkalot with help from the Igorot who were protecting their domain west of Nueva Vizcaya. These non-Christians raided the missions and attempted to dissuade their brothers from assimilation; hence, the settlement of Guinayongongan was abandoned in 1747. Such raids would provoke Spanish counterexpeditions.

With more troops and arms, Spanish expeditions in the 1780s became more brutal. The Bugkalot living in the mountains of Binatangan, now Munguia near Dupax, and Epayupay, now Payopay, were forced to surrender and reside in the Spanish-controlled center of Binatangan in 1887. In the same year, the Bugkalot living in the mountains of Casegnan, also Casecnan, particularly villages Casegnan, Bonabue, Dengue or Dangue, Yeguip, Pareguian, Caquiaoguen or Kakidugen, Yeguidmay, Canavuan, Payopay, Egat, and Biatan were forced to descend to an area that would later be known as the Franciscan Nantanaan mission not far from Binatangan. When the Franciscans left the mission, most Bugkalot simply returned to the mountains, prompting other missions to launch several other expeditions until the end of the 1800s. These expeditions resulted in the destruction of many villages that the Bugkalot had preemptively deserted to avoid capture or conversion. There were, however, some cases when peace pacts prevailed. In Camarag, now Echague in Isabela, Don Mariano Oscariz, military governor of Nueva Vizcaya, was successful in brokering a pact with the Bugkalot in 1847. In April 1891, Binatangan was converted into one of several politico-military territories and remained so until the end of Spanish rule in the Philippines. Like the comandancias politico-militar in Apayao, Kabugaoan, Itaves, Bontoc, Kiangan, Lepanto, Tiagan, Amburayan, Benguet, and Kayapa, the Comandancia Politico-Militar de Binatangan served as a Spanish political, military, and religious subcenter in North Luzon. Toward the close of the Spanish colonial era, Christian communities established along the Magat significantly curtailed Bugkalot contact with other non-Christian tribes.

As soon as they had established a civil government in Benguet, the Americans turned their attention on neighboring provinces. All the tribes in this vast territory were subsumed under the American-sponsored Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes that was established in 1901. By 1908, Secretary of Interior Dean Worcester had placed all the Bugkalot in Luzon under the jurisdiction of Nueva Vizcaya. At that time, other Bugkalot were living in Isabela, Nueva Ecija, Pangasinan, and Tayabas, which was later divided into Aurora and Quezon. In addition to using superior weapons against the local population, the Americans pitted various Bugkalot groups against each other as part of their imperialist divide-and-rule strategy.

The Bugkalot’s head takings were also used as reason for going after and conquering them. Worcester, who considered them “very troublesome,” cited Bugkalot head-taking incidents along the trail from Baler, Tayabas, to Bongabon, Nueva Ecija, as reason to reinforce troops and build roads in Baler in 1909. In addition to military forays into Bugkalot territories, the Americans introduced education and pacification as tools of civilization in Nueva Vizcaya. By 1909, at least two schools had been built in Macabenga and Campote. School superintendent RJ Murphy was tasked with establishing a community-based school in Macabenga. Murphy hired a teacher from Bambang who could speak Bugkalot and instructed him to convince the Bugkalot people to help build a school and shelter for teachers, and then build their own houses to form a neighborhood near the school. A Bugkalot or two were employed to teach language, calculation, and weaving. The Campote school followed the successful strategy at Macabenga; it was later closed down, but another one was built at Kasibu in 1910. The American government sent a Constabulary unit to this area and another unit to Nantaanan to secure the Bugkalot students and their families living near the school.

In 1918 to 1920, Lope K. Santos served as provincial governor of Nueva Vizcaya under the American colonial regime. To implement the American strategy of divide-and-rule, he classified the Bugkalot into two types: the “loyal” groups, who lived in government-controlled territory; and the “rebel” groups, who lived in the more inaccessible hinterlands. Thus, the Payupay and Benabe groups were deemed loyal and the Tamsi and Rumyad groups, rebellious. Governor Lope K. Santos recommended that loyal Bugkalot be used to full advantage to subdue the Bugkalot rebels, whose refusal to surrender to state control he called “traitorous resistance.” The loyal Bugkalot were hired as constabulary soldiers or guides. Thus armed with superior weapons, they engaged in revenge raids against the groups with whom they had a long history of mutual beheadings. This resulted in a bloody internecine war that lasted from 1919 to 1928.

The execution of colonial policies became less threatening in the 1930s when the Great Depression in the United States reduced government funding. Schools were closed down and constabulary soldiers were recalled, giving the subjugated Bugkalot the opportunity to escape to the mountains. A few younger Bugkalot were enticed to study under the government scholarship program as pensionados, established during the Commonwealth era by the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes. Meanwhile, the Ilocano were pushing into Bugkalot territory.

World War II forced the Bugkalot farther into the hinterlands; they were thus left virtually untouched by the Japanese except in the last days of the war. In June 1945, Japanese defensive positions in the Dalton Pass over the Caraballo Mountains, as well as in the towns of Aritao, Bayombong, and Bagabag, were taken by the Americans. The Japanese escaped into Bugkalot territory, hence triggering the Bugkalot’s massive evacuation, which one survivor likened to “cockroaches, numerous beyond count, crawling along the rattan strips of his floor” (Rosaldo, R. 1980, 130). The Japanese retreat into the mountain forests wiped out a third of the Bugkalot population, as they killed every Bugkalot on sight and seized all the food and property they chanced upon, consequently killing the Bugkalot with hunger and sickness. Some Bugkalot retaliated by beheading a number of Japanese, including one along the Abeka River, 10 in the village of Buwa, and two along the Reayan River.

Rosaldo (1980) notes that Bugkalot history during peacetime was marked by shifts in population movement—between concentration and dispersal—and in the practice of head taking. Some Bugkalot who had gotten used to lowland life before the war chose to return home from the mountains. However, increases in head taking were instigated not only by intertribal feuds but by lowland upheavals, such as the revolution in the 1890s and early 1900s and the Huk insurgency in the 1950s. When members of the Huk retreated to the Sierra Madre mountains after the government capture of their top officers, some fell victim to Bugkalot raids. Between 1956 and 1964, a total of 135 lowland Christians were killed by the Bugkalot.

By the 1960s, the Bugkalot were surrounded by the Ibaloy and Ifugao uplanders, who had been displaced by public works projects such as the Ambuklao, Binga, and Pantabangan dams. Neither could they escape the growing presence of the New Tribes Mission group, composed of Protestants who arrived at Taang, now Pelaway, in 1954. First to arrive was American Lee German, followed soon after by Marvin Graves, and then Tagalog Florentino Santos. With Taang as their base, the missionaries converted some 120 Bugkalot in the first two years of their mission. In 1959, Santos married a Bugkalot and moved to Gingin, at that time a benggi (center) of Bugkalot territory; here, he would continue his mission. By 1964, four airstrips at Puncan, Nueva Ecija had been constructed for more missionaries to enter. More airstrips built at Guingin, Siguem, San Pugo, Sinabbagan (now Landingan), Kawayan, Keat, Buayo, and Kakiduguen brought in a stream of missionaries, their families, and mission trainees. Their evangelical work, the spread of literacy, and the provision of social services dealt a significant blow to Bugkalot culture. The Summer Institute of Linguisics set about documenting the linguistic features of the indigenous population and collecting social and cultural data. By 1970, primers had been widely circulated and nine books of the New Testament translated into Bugkalot.

The logging boom in the 1960s, as well as road and infrastructure projects that accompanied it, added to the displacement of other Bugkalot populations and the influx of outsider population. By the early 1990s, seven large corporations were operating in Quirino, Nueva Vizcaya, Aurora, and other provinces.

Martial law in the 1970s further eroded traditional Bugkalot society. The ideology of the Marcos regime’s New Society entered the curriculum of a newly built elementary school; it established the Pan-Ilongot Federation, with the backing of the New Tribes Mission, and was integrated into the New Order; and head taking ceased as a result of unbridled militarization.

The Ilocano presently dominate the Cagayan Valley area. Wave upon wave of migrant groups have displaced the Bugkalot from their ancestral domain, which used to stretch over the sites of the Isabela towns of Echague, Jones, and San Agustin, to the Quirino towns of Cabarroguis, Aglipay, Maddela, and Nagtipunan. Most Bugkalot in Aurora have been pushed to the fringes of the province, particularly Maria Aurora and Nueva Vizcaya villages along the Abaca and Casecnan Rivers. The Bugkalot people are now confined to Sierra Madre barangays on the boundaries of Nueva Vizcaya, Quirino, Aurora, and Nueva Ecija. In sum, logging companies, churches, and new settlers invading their territory have ushered in the modernization of the Bugkalot.

Way of Life of the Bugkalot People

Swidden agriculture is traditionally the Bugkalot’s primary means of food production. Plants are cut down, left to dry, then burned during the penguma (preparation of the kaingin) from January to March. Unlike many groups engaging in swidden cultivation, the Ilongot do not cut down large trees. Instead, they practiced tengder (pollarding), a process in which branches of large trees are cut off to let sunshine into the newly created field. This is done from March to mid-April. The men transfer from tree to tree on rattan cables suspended 80 to 100 feet from the ground and fastened securely between trees. While “tearing down the dress” of the forest, they might sing and boast of their head taking experiences as loud as they can.

|

| Bugkalot mother in her garden (R. Rosaldo 1980) |

Felled branches are sun-dried, then burned. The clearing of the field’s debris is done by the men, as undergrowth must be uprooted and branches carried away. Planting is done by the women when the rainy season begins. The Bugkalot plant sugarcane, coconuts, rice, sweet potatoes, cucumbers, squash, and other vegetables. They gather shellfish from the streams and roots, and palms, fruits, honey, and beeswax from the forests. Food is prepared by boiling, roasting, or smoking, and preserved by smoking, salting, and sunning, such as with the pindang (sun-dried meat).

The Bugkalot today employ various methods of farming. Besides kaingin, also common are irrigated farming, permanent dry farming, and backyard farming. Primary crops are page or pagey (upland rice), bukam (aromatic rice variety), mait (corn), abitsuelas (kidney bean), balatung (mung bean), and kape (coffee)—the last three produced mostly for sale and not for subsistence. Secondary crops include gepang (ginger), gisantes (green peas), utong (beans), pitsay (pechay), mustasa (mustard), kamatis (tomato), mani (peanut), samal (cassava), kadriw (sweet potato), and tabaku (tobacco).

|

| Bugkalot man after spearfishing (R. Rosaldo 1980) |

Fishing and hunting are current economic activities as important as farming. They fish in the river with nets and traps, using poisonous berries as bait, for instance; they use bow and arrow when they dive to shoot larger fish. Their catch includes kadezap (cockroach of the river), kanit (worm of the river), iget (eel), beyek (goby fish; Tagalog - biya), alaken (frogs), tak-kang (crabs), nuto (snails), guddong (carp), tilapia, and kulanip (shrimps).

Atu (dogs) are used to track and hunt boar and deer. Every household keeps 8 to 15 service dogs, which are fed cooked food. Nevertheless, the Bugkalot do not consider dogs as pets. The closest Bugkalot term for “pet” is bilek but is used only to refer to piglets, house plants, and baby’s toys. Hunting, a predominantly male activity, is done either with net traps woven from strands of tree bark or with bow and arrow. Guns would later replace bows for hunting, especially after World War II. Hunting, which can be done either auduk (alone) or la’ub (as a group), peaks toward the end of the rainy season, which is at the beginning of every year, when abundant food sources have fattened up the animals.

The Bugkalot during the pre-Spanish times regularly traded goods with the neighboring Gaddang and Isinay within the Magat River Valley. Surplus meat, beeswax, and honey were bartered for metal weapons, salt, pots, clothes, and other necessities. However, the Bugkalot craft many of their goods, such as the ilayao, a multipurpose tool, and arms like the gayang (barbed spear), sinamongan (a larger and blunter ilayao), and eyaga (bolo), sheathed in kaaben (wooden scabbard) (Aquino 2004, 135). Sun-cured fawn skins are made into waterproof bags. Baskets and nets are woven from tubeng. A local yeast is used to concoct basi (sugarcane wine).

When the Spaniards came, the Bugkalot withdrew from the lowlands, cutting ties with their former trading partners who capitulated to Christianity. However, the need for certain essential goods required them to engage in trade, at times to their disadvantage, with shrewd Christians demanding more in the exchange. In one account, wealthy Bugkalot men procured several pairs of pants, shirt, and salakot (hat) for “many thousand leaves of tobacco.” In the 18th century, when the tobacco monopoly was imposed by the Spanish government on the lowland growers, the tobacco grown by the Bugkalot and other mountain groups was bought from the Bugkalot at a cheap price and then sold to lowlanders at bloated prices.

In more recent times, the Bugkalot’s main trade product is uwey (rattan), harvested from the forests of the Sierra Madre. To protect themselves from shrewd lowland dealers, some Bugkalot have formed cooperatives, whose representatives accompany the middleman’s truck that transports the rattan to the lowland buyers.

Video: The Bugkalot of Nueva Vizcaya - Not many Filipinos know of the Bugkalot of Nueva Vizcaya, of their history as nomadic farmers, as fisherman, as warriors and headhunters. The Bugkalot may have renounced the violent of their Ilongot ancestors. But in many ways, much of the archaic culture knowledge systems remains with them. These are traditions that they themselves have sifted through as they altered their identity. These are the practices that make the Bugkalot proud of who they have become.

In 1993, the national government drew up a plan to use a watershed from the Casecnan River for the irrigation systems of Nueva Ecija and for hydroelectric power. This would, however, displace several hundreds of households in Dupax del Norte, Dupax del Sur, and Alfonso Castañeda in Nueva Vizcaya. The Bugkalot strongly opposed the project at public hearings. Among the objections were the “dubious and spurious” nature of the consultation process, and the violation of the constitutional ban on non-Filipino entities engaging in extractive industries. Nonetheless, two years later, the Ramos administration, through the National Economic Development Authority, approved a Build-Operate-Transfer contract between the National Irrigation Administration and American-owned California Energy Casecnan Water and Energy Co. In 2001, the succeeding president, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, ceremonially switched on the valves diverting water from Casecnan and Taan Rivers to the Pantabangan reservoir. The following year, congressional hearings were held over anomalous provisions in the contract. Moreover, the American company had reneged on its many promises to the Bugkalot, including education scholarships to children up to college, employment opportunities, medical services, and construction equipment. In September 2013, some 500 Bugkalot from Nueva Vizcaya, Aurora, and Quirino staged a three-day rally at Pelaway in Castañeda, demanding a portion of the company revenues. The rallyists were violently dispersed by local police and the military. In 2015, concerns were raised over the Casecnan River drying up, which a Bugkalot tribal leader reported as severely affecting those whose livelihood was fishing.

The Bugkalot Tribal Community

An alipian, a community of several families, is headed by a kapanawan, who is assisted by a macotay. A kapanawan was chosen as the chief for his head taking prowess and his wealth, measured in terms of property. In 1929, a 30-year-old who had taken 42 heads was the most famous kapanawan among the Bugkalot. Today, leadership is based on ability and age, and at the highest level remains absolute and valid until death. When the chief dies, he is replaced by his assistant, and a new assistant is selected.

|

| Group of Bugkalot hunters, 2013 (Bugkalot Coffee Company) |

The ceremonial powers of the nigudu (shaman) can sometimes extend to sociopolitical matters. The beganganat or begenget (community elders) settle conflicts that may arise between the beganganat and the nigudu. Bugkalot common law prohibits murder, adultery, deceit, theft, work on each fifth day, wives’ disobedience of their husbands, and nonpayment of debts. Crimes are usually punished by fines and beatings. The families of offenders are partly accountable for the offenses; thus, they are involved in the settlement of both civil and criminal cases.

Territorial boundaries of Bugkalot communities are strictly observed. Crossing these is permitted only during intercommunity weddings, illness, or feudal revenge. Peace pacts between communities are negotiated by prominent representatives of the feuding parties, formalized by human sacrifice and a blood compact, and marked by lining trails with bloodstained arrows.

In 1919, Nueva Vizcaya governor Lope K. Santos, under the American colonial regime, proposed that the Bugkalot population be administered by a local civil government to be headed by chiefs loyal to the regime. Road building in Bugkalot territory was begun by Governor Lope K. Santos “to hasten the establishment of this organization,” as he put it, hence, primarily to solidify the US regime’s control over the Bugkalot people. In 1925, Governor Domingo Maddela, Santos’s successor, implemented his proposal by dividing the Bugkalot people into three distinct groups: the first, composed of the subgroups Kinalo, Kongkong, and Kasibu; the second, composed of Bua and Cannadem; and the third, composed of Oyao, Taguep, Belance, and Managgoc. Each group was headed by a “loyal” presidente (municipal mayor), who had a chief of police and four policemen, all of whom received government wages.

Bugkalot communities are presently administered by their provincial governments down to the local barangay units. The Bugkalot are organized by provincial organizations—one each for Nueva Vizcaya, Quirino, and Aurora—that operate under the umbrella organization called the Bugkalot Federation. With officials elected by the Bugkalot themselves, the Bugkalot Federation has been serving as “facilitator and conduit” of government programs and projects.

By virtue of the Indigenous People’s Rights Act of 1997, the Bugkalot received their Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title (CADT) by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples on 24 February 2006. A celebration was held in the municipality of Nagtipunan in Quirino, whose mayor, Rosario K. Comma, was then the Overall Chief of the Bugkalot Confederation. The CADT covers 139,691 hectares of land spanning parts of Quirino, Aurora, and Nueva Vizcaya provinces. It was smaller than what they had applied for and, according to the federation, erroneously excludes the Nueva Vizcaya towns of Dupax del Sur and Alfonso Castañeda. They have applied for a new CADT to cover those areas. These issues reveal a continuing political struggle between the Bugkalot and the settlers.

Video: Kultura at ipinagmamalaking putahe ng katutubong Bugkalot. Sa bayan ng Nagtipunan, Quirino Province, naninirahan ang katutubong Bugkalot na mga dating mamumugot-ulo o headhunters, Bagamat naglaho na ang kanilang kultura bilang headhunters, napanatili nilang nagbabaga ang kanilang mga tradisyunal na putahe. Ano-ano kayang Bugkalot dish ang kanilang ibibida sa atin?

Bugkalot Tribe's Culture, Social Organization and Practices

The Bugkalot belong to social groups of expanding size and scope—from families, households, and local clusters, to their largest social unit, the bertan. The bertan is a kinship system defined by the members’ descent from a common ancestor whose place of residence is recognized by members to be their common origin, such as “downstream, in the lowlands, on an island, near a mountain” (Rosaldo, M. 1980, 9-10).

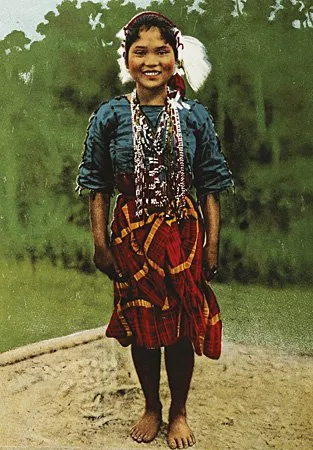

|

| Bugkalot woman (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Going by their origin stories, one bertan sees itself as unrelated to another if they have no common ancestor. On the other hand, the bertan is more a social feature that promotes unity through common concerns instead of disconnectedness. Thus, members of a bertan, though living separately in various settlements, can reasonably expect loyalty or assistance from one another. The Bugkalot population consists of 13 bertan: the Belansi (and the Butag), Benabe, Payupay, Rumyad, Abeka, Taang, Aymuyu, Dekran, Tamsi, Pugu, Kabinengan, Sinebran, and Be’nad. The Americans during their military campaign in north Luzon pitted the bertan against one another as part of the divide-and-rule strategy.

|

| Bugkalot family (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

While the more complex Bugkalot communities are socially stratified into the affluent, the middle class, and the slaves, the Bugkalot believe in inherent social equality. Thus, important activities such as raiding, celebrating, negotiating, and hunting are accomplished in groups. Feuds reinforce affinities. These feuds usually progress in four stages though not necessarily in succession: first, the recognition of an insult or a wrong such as when one’s manhood is taunted or when a suitor feels he is being unfairly overtaken in courtship; second, the beheading, during which raiding parties of four to forty men, both kith and kin, wreak their vengeance upon any member of the offender’s bertan; third, the covenant, which is settled a considerable period thereafter, when amends are ready to be made and manifested in social celebration; and fourth, the intermarriage or truce, or the resumption of the feud, during which the alliance is affirmed or severed, respectively. By far the most celebrated of such feuds was that between the Rumyad and Butag, which began in the 1940s for various reasons, mainly treachery, erupted in open battle in 1952, and only concluded by a covenant in 1969.

|

| Bugkalot family, 2013 (Bugkalot Coffee Company) |

Bugkalot social etiquette dictates moderate and cautious behavior to show respect and good intent. This code applies to casual greetings, covenants, and courtship. Abrupt actions indicate anger and hostility. Courtship transpires in stages gradually developing in social purview: initially, a private understanding between man and woman, expressed through an exchange of bunga (betel) and founded on the notion of tugde, meaning “to grow fond of” or “to become accustomed to”; next, the suitor’s formal revelation to the woman’s family, in which the woman defers to her suitor, and he in turn undergoes several tests, including working for her family; and finally, a public acknowledgement of the engagement, after which the woman can be courted by no other. The man’s family pays its respects to the woman’s family; in extreme cases, as in marriages of convenience (to end a feud, for instance), bride wealth payment is offered; otherwise, gifts of cloth, food, and drink will suffice. The man remains in the woman’s house on the first night, and so does his father, to ease the pain of parting. The wedding often takes place only after a child has been born from the union. During the wedding festivities, basi is served in large quantities to heighten the merriment. The guests eat with their fingers out of anahaw leaves, which they throw out the window after the meal. The remaining food is taken home after the feast.

The man provides wood, meat, and a new house if needed; he builds the fences and starts the kaingin. The wife performs the bulk of the household work. When transferring settlements, the women carry the heavier load while the men protect the family.

Once married, the man lives with or near his wife’s parents, whom he is forbidden to call by their personal names. When his wife’s parents grow old, they live with a younger married couple, customarily their youngest daughter and her husband. A Bugkalot male is at his prime between the ages of 35 and 44. He starts to master his culture and immerses himself in activities like singing, crafting, instrument playing, and orating. The Bugkalot man of advanced years is addressed as apu (grandfather), except by his children. However much he is venerated for his recollections and his position in the family, the aging Bugkalot is relegated to the margins of society.

In olden times, the mother-to-be delivered her child by herself in the forest. The next day she washed both herself and the child, returned home, and resumed her chores. She nursed the child for a week, after which she fed it by masticating the food and then spooning the mush into her child’s mouth. At present a woman about to give birth is assisted by the enpapaanak (birth attendant) and the tezab (the woman who presses on the mother’s abdomen to help move the baby out). After delivery, the enpapaanak wipes the newborn’s head and, after the inabong (placenta) has been expelled, cuts the umbilical cord. She uses the adomi plant to tie the stump of the cord attached to the infant’s navel and washes the woman’s genitals with water boiled with gepang and bayabat (guava) leaves. The infant is washed with water boiled with pakoy (red onion; Tagalog - lasona; sibuyas-na-pula) and kamoletlet leaves so that its skin will not darken. The mother is given gepang tea to drink. She may bathe as soon as she wishes, but her first bath is with water that has been boiled with inamo (Blumea camphor; Tagalog - sambong; Latin - Blumea balsamifera) and pakoy leaves. She resumes her regular domestic and farm chores after three days. If her infant is colicky, she feeds it a few drops of the leaf juice of apalya (bitter melon; Tagalog - ampalaya) before breastfeeding it. The baby receives its first solid food on the day it begins crawling.

The mother carries her child on her back while working. When the child is a little older, she may keep her child on a leash from the house’s central post, thus giving both herself and her child freedom of movement. At the onset of puberty, the boy undergoes laksyento (circumcision), which is done by the begenget.

Bugkalot marriages are generally monogamous and enduring. Divorce is brought about by crucial financial problems, the commission of a crime, or broader divisions between groups. For instance, relatively more divorces were recorded during the period of altering political alliances between 1952 and 1954, when the Rumyad-Butag feud weakened the ties between the Kakadugen and Benate bertan. Divorce is arranged by the parents of the estranged couple. The couple’s children are divided: the daughters with the father, the sons with the mother. If the woman commits the offense, she returns the wedding presents to the man’s parents.

The stages of the male life cycle are characterized by the cultivation of certain skills: As a youth, the male learns how to work, and as an adult, how to speak. From the beginning, the boy, with bow and arrow in hand, is initiated into gender-specific activities like hunting and foraging. Upon reaching puberty, he selects a name, usually derived from an object of nature, which he retains until he moves residence or when an evil spirit causing illness and misfortune needs to be exorcised. Manhood is attained through various ordeals, most importantly teeth filing, head taking, and marriage. Teeth are shortened for increased strength and sanitation. The excruciating pain experienced during the ritual is remedied by the application of a warmed guava twig or a batac stem. The art of kayaw (head taking) elevates a male youth from the station of a novice to that of a full-fledged adult. The goal is not to collect heads but to take at least one head, for the ritualistic “throwing away” of a body part to symbolize purgation or an unburdening of life’s load, such as grief over the death of a relative, grievance from an insult, or frustration over remaining a siap (novice hunter) when others of the same bertan have moved on to a higher status.

Video: Tribo ng mga Ilongot, dating tradisyon ang 'Pagpopotog' o Headhunting

The Bugkalot’s reasons for head taking include protecting one’s territory from intruders, as in the cases of intertribal wars; defying foreign rule, as in the cases of Spanish, American, and Japanese invasion; and appeasing spirits and deities. Their head-taking practice is an expression of their philosophical notions of liget and beya. Liget is the convergence of such strong emotions as rage, envy, creativity, and passion, mainly associated with younger men. It is more complex than the simple English word “anger.” Beya is the “mature display of cultural knowledge.” Both are viewed by the Bugkalot as integral parts of their life cycle that promote their society’s survival and advancement. Strong energies related to the liget dwindle with the accumulation of knowledge through age and experience manifested by the beya. A “perfect balance” transpires during the symbolic casting away of the head. The Bugkalot believe that this is also when a head taker receives the amet (heart or life force) of the slain, for which he now has the right to wear the beteng (earrings). American anthropologist Albert Jenks (1905, 174) erroneously reported that the Ibilao, also known as Bugkalot, practiced head taking at the end of every harvest season as a requirement for marriage as well as a form of requital for “debt of life.” Although a status symbol, head taking is not a prerequisite to marriage. However, during the head-taking era, Bugkalot women had a low regard for a man who had not taken a head.

Head taking can be either during a ngayu or ngayao (raid) in distant areas or ka’abung (in the household) for unsuspecting victims. A foray requires the chief’s consent, initiated by feasting, with the participation of a ngayu, a party of an even number of male relatives. The warriors ambush their victims in various ways, such as by encircling a person on a trail or by burning a house and killing its fleeing occupants. The warriors cut the body parts believed to contain the essence of the person’s strength: the head and some toes and fingers. (The head is sacred, and rubbing another person’s head is considered derogatory.) The severed parts are cured then stored for ingestion during illness or at a consecration. Another feast concludes the ritual, after which the prized head is buried. The skull is later exhumed and hung from the rafters of the victor’s house.

The Bugkalot ceased the practice of head taking in the early 1970s. This was due to various factors: rumors of persecution and punishment by firing squad during martial law; evangelization mainly by the New Tribes Mission; an intertribal peace pact earlier initiated by religious, government, and private groups; and, the increased displacement of the Bugkalot following the incursion of other ethnic groups into their territory. Between 1967 and 1969, only one head taking celebration, demonstrating exuberant gong playing, boastful storytelling in song, and group singing, was recorded. In 1974, the same Bugkalot group listened to the recording and were so pained at the reminder of their core value now obliterated that they could not sit through the recording. As their spokesman explained: “When I hear the song, my heart aches as it does when I must look upon unfinished bachelors whom I know I will never lead to take a head.”

A barangay sufficiently remote from the poblacion (town) would have a number of resident enpapagak (healer priests) and enpapaanak. This is exemplified by Brgy Talbec in Dupax del Sur, Nueva Vizcaya, where six enpapagak and enpapaanak serve a population of 63 households of 296 members, 85% of whom are Bugkalot. The enpapagak are bearers of an ancient knowledge of the medicinal properties of plants and trees surrounding them, as well as knowledge of the rituals for exorcising the malevolent spirits causing illness in a person. Because these plants and trees are endemic to their locale, the Bugkalot names for them have no known English or Tagalog translation.

Tuge’t (wounds) are healed by a poultice made from the juice of plant leaves, such as those from the dug-ga (heartleaf hempvine; Tagalog - bikas; Latin - Mikania cordata), bulinangan, gine’segeten, aymbongabon, butalangan, kalabangan, and but’ngog, as well as juice from the shavings of the roots of the olangkeyo (cassava; Tagalog - kamoteng kahoy; Latin - Manihot esculenta). The kale’ge’mge’m plant is for katno ole’g (snake bites), and the bark of the adewe or adeve’y (ironweed; Ilokano - agas-moro; Tagalog - tagulinay; Latin -Vernonia vidalii Merr) is for a tuge’t ng baril (gunshot wound). The juice extracted from shavings of the bark of the ungkop is applied on gusing (a sprain).

The juice extract from the roots and leaves of the inamo is rubbed on the whole body of a person stricken with mepe’pe’gengan (fever). But the roots of the same plant may be brewed and drunk by someone suffering from kinapatan (stomachache) or ampepenage’totan (urinary tract infection). Chewing the roots and leaves of the getagete plant relieves a me-eebot (toothache). Rubbing a mixture of lime powder and the leaf juice of the biaw (a kind of grass; Ilokano - runo; Cagayan - Aeta birao) on the forehead relieves e’n-agte’ng (headache).

Eye drops to remove a napsit (eye irritant) are made from the leaf juice of the anayop, nag-gi, or the adewe. For benmoseng (a punctured eye), a few drops of breast milk mixed into the leaf juice add greater relief. Gadot (scabies) is treated by washing oneself with the brew. The juice extract of bongog-bongog leaves is applied on ugot (boils), and that of kad-dew leaves on gu-lad (ringworm). The sap of the nadiya (narra) is rubbed on dilat (mouth sores). One who is prone to mamamayongbong (nose bleeds) is advised to drink a concentrated brew of the tak-deng plant three times a day.

A poultice of coconut oil mixed with the heated leaves of bayatbat (guava; Tagalog - bayabas; Latin - Psidium guajava), or bogiew, also bagiw (moss or lichen), is placed on the abdomen to relieve constipation or urinary tract infection. Unlo-yot (diarrhea) is cured by frequent drinking of the brew from the roots of the pok-kot plant. Taday (lemongrass, Tagalog - salay) may be brewed and drunk by one afflicted with pantat (kidney stones). A person afflicted with betok madsisduzan, which is also caused by kidney stones, chews and swallows the juice of the stem of the te-gang plant. Drinking the brew from the roots of the kalupe’pet (bashful mimosa; Tagalog - makahiya; Latin - Mimosa pudica Linn.) cures urinary tract infection and relieves avan di me’degong (menstrual pain); however, this is forbidden to pregnant women.

A poultice made from the shavings of the roots of the adiew (pine tree) relieves madedepe’zow (joint pains). Massaging one’s neck with a mixture of coconut oil and the heated leaves of the ageteve’n relieves ok-ok (cough). A person with mapopogangan (malaria) is steamed with boiling talipangpang leaves; another cure is a vine of dempugan leaves tied around the patient’s waist.

Matetak-dot (falling hair) may be arrested by rubbing one’s scalp with the juice extract from taday (lemongrass, Tagalog - salay). Sinambongolan (swollen penis) is treated with a poultice of the extracted juice of pinagototan leaves. The graver condition of bengkel-bengkel nagoteg-goteg (swelling in all parts of the body) is treated with the steam from lepong leaves that are placed on a heated stone. A terminal illness, also called matetak-dot (possibly cancer), is first manifested in the swelling of one part of the body, and gradually spreading to the rest of the body. A cure is possible with the steam from the bozoy plant that is placed on a heated stone.

The Bugkalot mourn their dead for a week. During mourning, work ceases, and eating salt is taboo; only rice is allowed. A wake is held while the blanket-shrouded corpse lies in a house. It is left to decay on a bamboo table in the house, which is later set on fire; the neighbors abandon the near surroundings thereafter marked with a fire tree. Some corpses are buried in a sitting position. Personal weapons, utensils, and ornaments are laid beside the corpse. The funeral rites end with a village celebration, where only fish and rice are served. The nearest kin of the deceased, such as a parent or a spouse, makes solemn vow as abstaining from a certain food, abandoning a piece of land, or refraining from fishing in a designated area. Otherwise, village life returns to normal. A man’s eldest son inherits his property. A woman leaves no material legacy.

The Bugkalot Tribe Religious Beliefs, Rituals and Practices

Spanish chroniclers observed that the Bugkalot believed in one supreme being and that they considered Christians idolatrous for praying to gods manufactured from wood. However, over centuries of acculturation, Bugkalot religion has become syncretic, as evidenced by the names of their mytho-religious characters. The traditional Bugkalot believe that Kain and Abel are benevolent gods and creators of the universe who live in heavenly bodies. Because they are invisible, they are believed to be moving when keat (lightning) and kidu (thunder) occur. The stronger Abel created the lowlands; Kain, a headhunter, created the mountains, the Bugkalot people, and culture. Together with their emissaries Binangunan or Kabuligian, both are worshipped during feasts. Food and wine are set on a small bamboo table covered with red cloth. The priest shouts the invitation to them that they may be pleased to bless the people with good health and harvest.

Some Bugkalot pay homage to nature, as personified by Oden (rain), Elag (sun), and Delan (moon). Delan has several phases because Elag covers her with a baga-o (basket) when they quarrel. Fire also occupies a significant place in the Bugkalot belief system. Before a hunt, the dogs and weapons are passed through the smoke of a fire. The leader of the pack is the last dog to be passed. It is rubbed with its owner’s saliva while prayers are sent to Gemang, the guardian of wild beasts. Deadly reptiles are also shown respect; thus, a piece of chicken may be left by the river for crocodiles to eat.

The spirit world is inhabited by good and bad anito (spirits). The ayeg oversee the larger scheme of things, righteously giving rewards and punishments. Sickness is associated with the saiden (malevolent spirit), also called agimongor agimang, and ceremonies involving the use of herbs are led by the enpapagak as he asks the spirit to depart from the sick. These spirits reside in the gongot (forest), particularly in trees, pinget (river), and eoma (farm). An illness that is believed to be caused by the agimang is betong sepanon, manifested by the stricken person’s memory loss and hallucinations. A cure is the steam from boiling bulakot leaves.

Headhunters believe that when a man is killed, he leaves behind his heart or life force that can either be a beteng or an amet. The beteng generally afflicts the living, whereas the amet attaches itself to the beheader and thereafter can no longer cause problems to the community. The achievement of the amet is the spiritual aspect of head taking.

The palasekan (dwarfs) play a part in individual lives. Willful and whimsical, they must not be displeased lest sickness befall the offender. One should always carry a light to avoid encroaching on these creatures of the dark. However, they can be very helpful in bridging the known and the unknown, such as in conveying messages from the dead and advising priests on the treatment of the sick. They are well-informed about human affairs, enjoy worldly pleasures like drinking basi, and play favorites among earthlings. The use of charms, amulets, and magic acknowledge the spirits. Balete trees, where they are said to lie, stand undisturbed. Caves are likewise revered, for they house the agimong and betang, the spirits of ancestors.

Omens guide daily life, especially in important activities. Animals are key figures: A bird on a dead tree indicates misfortune; bathing a cat brings rain; a snake in a traveler’s path portends his murder; and a hunt is discontinued when the howl of a dukpaw (owl) is heard.

The magnigput (priest) supervises religious education, advises the community on related matters, and sanctifies feasts and social occasions from birth to death. His position is hereditary, being carried down to the eldest son or nearest male relative. Among the Bugkalot feasts are the burni, for births and sickness; dumiti, for postharvest thanksgiving; langaya, for headhunting; aimet, for game hunting; and baleleong, for the ritual of anointing young children. In the langaya and aimet, the aymuyu (ritual leader) slaughters a chicken and examines its liver for signs on whether to proceed with the hunt. The ritual also seeks guidance from the agimeng (forest spirit).

The baleleong is an extravagant affair hosted by affluent families. Wreaths of leaves, each with a dish for every child, are hung on the beams. The priest carries the male child, who wears the wreath on his head. After praying to Abel, the priest makes a cross on the boy’s forehead with pig’s blood. Both the boy’s ears are pierced. Separate rituals are held secretly for boys and girls. Boiled spring water instead of blood is used by an elderly woman to anoint the girls. The girls’s meal immediately after the ritual is restricted to rice and fish. It is believed that an error in the execution of the ritual will shorten the child’s life.

|

| Bugkalot men and women performing a ritual prior to hunting, 2013 (Bugkalot Coffee Company) |

Bugkalot spells and ritual prayers are classified into the sambal, aimet, and tugutug. Sambal are spells that involve the use of herbs and plants to treat illnesses. These spells cite temporal images of “purification and safety,” such as thorns that protect plants from scavengers, metals that are immune to scratches, and trees that are protected from forest fire. The nawnaw is a very elaborate speech characterized by “hyperbolic metaphors, redundant rhythms, and stereotyped lines” (Rosaldo, M. 1973, 197). An English translation of a Bugkalot spell follows (Rosaldo, M. 1972, 85):

Hey, all you spirits, come listen now!

Here are your thighs, spirit;

May your thighs be twisted, spirit,

if you do not make this child well.

Open his heart, spirit; make him light, spirit.

May he spin like an eel away from sickness.

May he be as clean as glass.

Here are your fingers, spirit;

I steam your fingers, spirit.

They will be knotted, spirit.

Make him well now!

Aimet are spells related to Bugkalot agriculture and hunting. They invoke abundance in harvest and game but also discourage excessiveness. A farmer can ask to be dazzled by an abundant crop yield, whereas a hunter can implore to get indigestion if he eats meat that comes from excessive hunting. Tugutug are spells that disrupt ancestor spirits and shield hunters and farmers from any unnecessary activities. The tugutug are invoked at the gelibdib (edge) of the forest because the Bugkalot believe that it is where their departed ancestors cause them grief and unrest. On the other hand, the aimet are invoked at the bengri (center) of the field or forest where the home of the agimeng and madekit (maiden rice spirit) is found. The Bugkalot also refer to agimeng as irungut or “from the forest” and madekit as i’uma or “from the field” (Aquino 2004, 148-49).

The Bugkalot population that is the majority in barangays Landingan, Wasid, San Pugo, Matmad, Keat, and Guingin or New Gumiad in Quirino, and Abaca and Talbek in Nueva Vizcaya, is predominantly Protestant, an outcome of the New Tribes Mission that dates back to the 1950s. This Christian fundamentalist organization, of US origin, believes in the infallibility of the Bible and teaches the importance of salvation based on personal, spiritual growth. Other religions, such as Roman Catholicism and Union Espiritista, are practiced in other barangays populated by the Bugkalot: Nueva Vizcaya’s Bua, Alloy, Siguem, Pacquet, Muta, Kakiduguen, Pao, Binnuangan, Belance, Macabenga, Oyao, Ganao (Lingad), Kimbutan, Biruk, and Yabbe, and Quirino’s Mataddi and Giayan or Guiayan.

Bugkalot House and Community

A Bugkalot settlement, dense or dispersed, is composed of some 4 to 11 houses. In the past the Bugkalot built their abung (houses) on trees in this manner: Four trees growing near each other to form the corners of a square were cleared of their branches so that the house could be built atop it. Alternatively, houses were built on tukod (posts) raised two to three meters from the ground for protection.

The kamari, which is the boxlike domestic house, would have detag (floors) and platforms of bamboo or rattan-bound sapling stems held by wooden tiken (supports). The gubek (walls) were of tree bark, later of palm, rattan, or grass such as lasaw (wild cane; Tagalog - talahib), gawakan (serillo dulce; Latin - Schizachyrium brevifolium), or lumnuan (bamboo). The roof, thatched with either kanawan (cogon) or beyaw grass (spear grass; Tagalog - sibat-sibatan) inclines toward the apex, which is ornamented with an eteng, a wood fixture curved like horns or a hornbill—a Bugkalot trademark. The gaun is the smaller, temporary field house.

|

| Casibu Settlement Farm School in Nueva Vizcaya (The Philippine Craftsman, January 1915, American Historical Collection) |

Houses were fenced in by dead trees and foliage, and approached by way of a secret entrance barricaded with puas (bamboos stakes), the foot of each thrust into the earth. With the arrival of Spanish colonizers, the Bugkalot built their villages on mountain summits for defensive vantage positions that were protected by steep rocks or dense forests. Trails leading to villages were well hidden and strewn with various traps. Different pathways were used to allow time for vegetation to cover the trails.

|

| Rice granaries (R. Rosaldo 1980) |

The modern Bugkalot house is about 4 x 5 meters and elevated some five meters above the ground by wooden posts. The basic framework is of bamboo, rattan, anahaw leaves, and runo stalks. The house may shelter several families. Each family reserves a corner, which is slightly raised and has its own fireplace and storage area. All sleep on the unpartitioned sunken floor at the center of the room. Animal skulls are used to decorate the interior of the house. Dogs guard the single door, which serves as both an entrance and exit. A platform may be constructed outside and the bottom of the house used for domesticated animals.

The Bugkalot house traditionally contains the following items: a metal food container and frying pan; spoons, ladles, and drinking bowls fashioned out of coconut shells; a bamboo trunk serving as a water container; bamboo tubes to cook rice or corn in; and a clay stove.

Bugkalot Traditional Attire and Accessories

Video: Mga katutubong kagamitan at kasuotan ng mga bugkalot

Bugkalot men traditionally wear a be-e (loincloth) held around the waist by a cagit or kaget of either brass wire or woven rattan. Gabed (a piece of bark cloth) is wrapped around the legs and tied at the front and back with a string belt. The tabengel (red headband) is worn by men, the hair tied at the back either in ilde (snaillike) manner or simply held by a parigo (strap). A beaded necklace and waist ornaments are adorned with horsehair, preferably white, which is believed to be pleasing to the anito. A pair of batling, also batleng (earrings), is suspended from the upper ear lobes. Each batling is five inches long, carved off the bill of a kalaw (rufous hornbill). Part of the kalaw’s bill is bent to around 130 degrees, purportedly to represent “focused energy.” The kalaw, whose beak has the color of blood and whose cry is like a victim’s scream, is a symbol of headhunting. (There is also a striking resemblance between the words “kalaw” and “kayaw” or “head taking.”) The batling are adorned by tassels of several dilap (shells), and brass plates accentuate both ends of each bill piece. The batling symbolize manhood, especially if the wearer has taken an enemy’s head.

|

| Bugkalot man wearing a hornbill headdress called panglao, 2014 (John Caanawan) |

The men’s most elaborate headdress, called panglao, is worn during ceremonies to invoke the magical powers of the red hornbill. It consists of a rattan skullcap and the entire tukbaw (bill) of a kalaw. The beak and the skullcap are joined together by one or two pieces of wood or rattan. The headpiece is embellished by tassels and other designs made of copper, brass, and shell beads. Fancy headgear identifies a successful headhunter. An ear pendant represents a man’s first kill. Notches are added either on the bill or the earlobes to indicate subsequent successes.

|

| Bugkalot boar’s tusk armlet (Photo by Masato Yokohama in Maramba 1998) |

The men wear binintug (metal band) on their left arm and several rings on their fingers. A handy bag containing arrowheads, flint, crocodile teeth, betel nut, and other articles complete the male apparel. The boys are set apart from the men by a bosiet or bisiyet band around one of their leg calves.

|

| Bugkalot bolo (Robert John Pepoa, philippinetribalarts.com) |

The women’s agemet (traditional attire) consists of the agde and anseng. The agde is a wraparound skirt made of bark cloth and held in place at the waist by a kaget of rattan or wire. The ansengis ablouse or vest that exposes the midriff. Although the Bugkalot do not weave cloth, the women are skillful embroiderers and make cotton tassels, which they tie on their horsehair ornaments. Accessories are kalipan (earrings), brass armbands, and small bells.

Filed and blackened teeth are considered aesthetically pleasing, and long hair is preferred by both men and women. Children are unclothed until prepubescence. Nowadays, though, the Bugkalot attire and accessories have been replaced by the conventional, western-type clothes worn by lowlanders.

Bugkalot Literary Arts

The Bugkalot convene a pogong (oratorical discussion) from time to time to settle differences. Traditionally, participating men persuade others by means of the amba-an, which is more elaborate, witty, and creative than everyday speech. It is an allusive way of speaking characterized by “iambic stresses, phonological elaboration, metaphor, repetition, and puns” that are features of poetry and song. The pogong is still practiced today in the settling of land disputes, for instance, but the style is now nata-upu, prosaic and straightforward.

Although many Bugkalot dimolat (folktales) derive from practical jokes, some reveal fragments of Hindu epics. These tales represent the Bugkalot worldview and value system, such as the virtues of courage and strength as manifested in physical exploits. They also suggest that to the Bugkalot, cruelty is justifiable but kindness is always a virtue.

The dimolat have no fixed classifications. There are origin myths, legends, animal tales, märchen, and occupational tales. The dimolat can be told in two ways: briefly, during moments of respite from work or whenever an expert storyteller is unavailable; or comprehensively, when time permits or during idle evenings. A master storyteller, usually an old man or woman, chants in a generally monotonous tone. Lively tunes are rare. The narration follows the measure of the tune; for this purpose, various literary and rhetorical devices can be employed. For example, meaningless syllables are added or meaningful ones deleted to fit the musical meter. The plot being secondary, the pleasure of listening to a dimolat comes mainly from the storyteller’s manner of narration.

The origin myth “Na Nanggapuan Min Ilongot” (How We Became Ilongot) is a tale of Bugkalot ancestry. The god Kain created a man and a woman. They married and lived in a hut in the mountains. There the woman conceived and bore a son. Later she bore a daughter. When the two children grew, their parents asked them to marry. This process continued until the mountains were populated. The descendants have since pursued the economic activities of their forebears.

A folktale that affirms the high honor afforded head takers is that of a young archer named Pana, who loved Anang, a beautiful daughter of the chief of a neighboring community. One day Pana went on a head taking expedition. Upon chancing on a lone maiden, he killed her and cut off her head and fingers. Then he threw her body into a river and removed the brains and hair from her head. These he presented to Anang’s father as proof of his courage. The wedding followed, during which the head was used as a wine bowl. Finally the village folk took turns dancing around the head in joyous celebration.

Legends are the Bugkalot’s explanations for worldly phenomena. The tale “Nempangngon Ma Bantog Duag Ma Lemot To” (Why the Lizard Has Two Tongues) recounts a contest between a lizard and a crocodile who agree that whoever stays longer underwater would have the tongue of the other. The competition lasts several days, but the lizard cheats by coming up for air. Unaware that he has been cheated, the crocodile eventually surfaces and acknowledges defeat. So the lizard wins the crocodile’s tongue.

|

| “Why the Lizard Has Two Tongues” (Illustration by Harry Monzon) |

Some Bugkalot animal tales are also origin myths. In “Sayma Nang-gapuan Ma Bulangna” (The Origin of the Monkey), a rich but selfish man owns a large farm and much property. His laborers are always hungry, for they are barely fed. One day the master decides to start a kaingin. To make the clearing, the laborers cut the trees down then proceed to the forest to collect rattan to make tabigoc. By midday they have completed their tasks but are very hungry. They climb the trees and cut down branches and twigs. Weary and dazed, they place the rattan between their legs. These turn into tails, and the men themselves are transformed into monkeys. The master discovers his hungry laborers in this state.

One Bugkalot animal tale, “Kalabin tan Saima Kolugo” (The Bat and the Owl), which is in dialog form, reveals the Bugkalot’s clever wit at deliberately erasing distinctions among strict categories and reversing them to create surprising truths. Here is an English translation (Wilson 1967, 76-78):

Bat: Owl, you look like a cat.

Owl: And you, a dog.

Bat: You’re mistaken, I am a bird;

wings are my gifts, and trees, my home.

Owl: But feathers you have not.

Bat: I fly. But you look like a cat.

Owl: What do you eat?

Bat: Fruits and nothing else. And you?

Owl: I eat rats and little birds.

Bat: If I were a dog, I would be eating

flesh as you do.

Owl: I see your point. I suppose we are

half bird and half animal.

Dreams in Bugkalot tales are portents of the future. An occupation tale about a kind and industrious couple shows how dreams are used to predict the unknown. In the settlement of Tamsi lives an industrious couple, Tunggi and his wife Luddi. They hunt and plant camote (sweet potato). One day Luddi dreams of a famine. In that dream she is advised to plant many sweet potatoes and sugarcane. Luddi and Tunggi obey the dream. In a month the sugarcane grows. The couple digs up the potatoes and fills one corner of their house with the harvest. The famine strikes. The couple shares their bounty with those who come begging for food. After the famine, Tunggi is made chief of the settlement, and Luddi continues to be popular among the folk.

|

| Scene from a Bugkalot tale, where the character dreams of falling into a pit trap (Illustration by Harry Monzon) |

The dream device may function in a tale as an oracle, that is, a dream foretelling the future metaphorically. This is shown in the tale of a hunter who lives in the Ipango forest. One night, after an unsuccessful hunt, the hunter returns home to sleep. He dreams of falling into a pit trap so dark and deep that his breath almost escapes him. When he awakes in the morning, he puts thoughts of the dream aside and goes hunting. He sights a deer and trails after it until darkness covers him. He finds breathing difficult and recalls his father’s stories. He realizes, as if jolted by a premonition, that he has been swallowed by a snake. With his knife he cuts himself free from the snake’s stomach. He runs to the village and tells the others of the creature. They seize their weapons, return to the site, and kill the snake, the meat of which they share among each other.

Bugkalot Tribe Song, Dance and Rituals

Bugkalot rituals and feasts, marked by song and dance, are performed to solicit the blessings and protection of the gods. Moreover, daily livelihood tasks as well as the life cycle—consisting of courtship, marriage, parenthood, and death—present other venues for the Bugkalot performing arts.

Bugkalot musical instruments produce unusual sounds. Such instruments can be classified into two: those played only to provide rhythm for dances, and those for other purposes. The only recorded example of the first type is the ganza (brass gong ensemble). Examples of the second type include the bamboo or brass mouth harp; the kuliteng (bamboo guitar); the bamboo zither, which can be either plucked or tapped; the bamboo or bark-and-skin violin; and the nose flute.

Bugkalot vocal music is shouted or sung during ritual dances and celebratory rites. The buayat is a triumphant head taker’s song giving a vividly detailed, much embellished account of his kill. It is sung in “short, heavily rhythmic lines,” with lyrics extemporaneously composed: “I went to where the sun sets and fell upon a giant”; “I would not sing your lines, buayat, had I not tossed a Christian’s head far down a muddy path.” During a head-taking celebration, which lasts the night, all the men with a glorious history of head taking exchange buayat, each trying to outdo the other in recounting the greatness of their own exploits. As more iyab (sugarcane wine) is imbibed, the exchanges rise to a crescendo of good-natured barbs, taunts, and insults. The buayat is believed to “purify” and remove the “anger” from the household of the head taker while at the same time giving him more strength (Rosaldo, M. 1980, 54-55).

Songs of a personal nature and are thus performed solo are the baliwayway (lullabies), cradle songs, and love songs. Here is a mother’s baliwayway to her son (Wilson 1967, 108-10):

Ay os’song bukod nito ta uc’kit capa,

Taan ca pa no be’dac

Du bucud si’gudu no simican capo’

Sigudu agcapo andan’ge;

Do an’gen isipel con lagem

Ta alim’bawa we maduken bilay mo

Sicapo ma manalima di’ke.

I say ma ibigec dimo ay nongo capo,’

Ta inki’taac pud uma antala’baco,

Ta we pañga’gaan ta no biayta,

Ta camuem pon sumi’can

Atembawa sumican capo Ossong,

Sica ma mañgoma

Ancayab’ca mad kio

Tan de gan moy di.

Ta we poy paguean co,

Pañgagaan ta no canan’ta.

(My son, now that you are still young,

I compare you to a blooming flower;

But, when you grow to be a big man,

Maybe you will be a naughty youth;

But, though my suspicions are like that,

I just bear them all

Because, if you will grow, and

have a long life,

You shall take care of me when I grow old.

I am then urging you to sleep,

So that I can go out to the field and work,

To plant; so we may have something to reap,

to sustain our life:

So that you will grow easily.

And, if you will grow to be a man, my son,

You shall take my place on the farm.

You shall climb the tall trees in my stead;

Cut the branches and the trunk.

So that we shall have some place

to plant rice

To sustain us, while we are still alive.)

When the child has grown bigger, he or she may be put to sleep with a cradle song, such as this one (Wilson 1967, 107-108):

Otoyo nappalindo walaan canman

Tay asimpogong noy kinnolayab noy lambong.

Imepat a nakigeb. Noy saguet.

Ipipian nong-o

Mam’bintan ka ñgomka manibil

no umuwit inam

Gimat’amam nanganBekeg ma talabacon inam

Ta kagamakan de no unka muka sumikan’

Tano we kadedege ma Apo sin Diot,

Ta iya’dan na ka no madukem biay’mo

Ta bukod no sumikan ka

Sika po, manalima mad bugan’gat ta.

(A small boy who plays with flowers

With his small cloth he climbs

the yellow bell-flower.

It bends over and breaks. He falls.

So, you had better sleep soundly,

Then cry when mother comes.

Father went out to hunt deer for you,

In addition to mother’s work

With the purpose of making you grow.

And if our Sire grants his help to you,

And permits you to have a long life,

When you grow old,

It’s then your duty to support your parents.)

Love songs are sung among the youth who have reached adolescence. The following is the love song of a girl to her suitor (Wilson 1967, 110-11):

Talumpacdet, talumpacdet,

Papan ginsolaney.

Tumacla ginlamonyao,

Kadiapot otog bilao,

Bilao dipo alandeden.

Gapuca ñgo upad longot,

Aduan toy sulimpat;

Admo deken weningweng.

(Wait for me, wait for me,

There where you cut trees.

And let’s go and gather oranges.

We will eat them on the grass,

The grass where our houses are.

You have been in the forest,

And you didn’t get any bean-shooter;

You didn’t bring anything for me.)

Bugkalot dances are relatively free of foreign influences. Their head-taking dances are emotionally powerful, as these are reenactments of the head-taking deed itself. The movements are strenuous and betray internal stress. As in many head-taking societies, several heads were prized possessions and were presented as gifts during courtship. Actual heads are no longer used today.

|

| Bugkalot war dance, 2014 (John Caanawan) |

The tagem, or post-head-taking dance, is still executed according to custom. While the women play the kolesing (bamboo zithers), counterpointed by the sticks and the litlit (guitar with human hair strings), the men dance with their weapons, moving in a vigorous and trancelike manner. They may mock and tease the head that they have cut, even as they engage in a friendly battle to show their prowess in battle. The women later join the men and dance with equal intensity.

Video: Bugkalot War Dance

Such a dance took place in 1917 on a cleared hilltop after a successful head-taking expedition. Severed heads and jars of rice wine were placed on a mat that had been centered on the clearing. The heads served as wine bowls after the scalp and the surrounding top portions had been cut off and the brains removed. Only the men danced around the mat while the rest moved, shouted, and sang to the beat of the brass gongs. The members of the expedition chanted their adventures and demonstrated how they made the kill. Another war dance has two warriors armed with bolo (knives have now been replaced by sticks) and shield, simulating a combat with agile steps and fluid arm and body movements and smooth steps.

The Bugkalot also perform dances unrelated to war. Most noted of these are the dallongtayo, the kullon, and the ditak, which are all economic dance rituals celebrated by the entire village.

A headhunting celebration consists of performative acts building up toward the buayat: The men inhale the scent of ginger to rouse themselves to anger; they dare the boys to behead a chicken that is tied to a stick for the occasion; they rub their wives and daughters with brass, which imbues strength. Finally, they gather around the women already seated in a circle and chant their buayat with great intensity. The women join them with equal intensity but always a beat behind, in “choral counterpoint.” The chanting, done at the top of their voices, lasts all night (Rosaldo, M. 1980, 54-55).

Documentaries, Films and Videos Featuring the Bugkalot

Nueva Vizcaya, 1973, is a feature film later dubbed in English for the American audience under the title The Headhunters. It ostensibly depicts the province’s search for peace amidst the terror sown by the “most feared minority group” in the region, the Tarican. It is a thinly veiled allusion to the Bugkalot, whose headhunting tradition the national government had long been attempting to end. Released during the first year of martial law, the film aims to legitimize military presence in Sierra Madre, which is also a stronghold of the Communist New People’s Army. The film begins with the character played by Vic Vargas taking the heads of two unsuspecting, lowland Christians. Head taking, according to the film, is required of a Tarican man to be able to marry. He and his raiding party take the two heads back to their tribe’s cave and offer them to the delighted chief and the woman he means to marry. A wedding soon follows while tribesmen and women dance around the heads placed at the tip of two spears. Such a portrayal of the indigenous people of Nueva Vizcaya perpetrates a false, simplistic notion begun by such American anthropologists as Albert Jenks (1905), stemming from an indifference to the complex social and religious premises of the head-taking practice. Notwithstanding its misleading assumptions, Nueva Vizcaya won the Filipino Academy of Movie Arts and Sciences (FAMAS) Award for best picture in 1974.

The 38-minute documentary film The Headhunter’s Shadow, 2000, produced by the Philippine Human Rights Informaton Center (PhilRights), shows the effects of the Casecnan Dam on the Bugkalot. This is the most recent episode in a long history of the Bugkalot’s displacement and acculturation, caused by Spanish and American colonization, the Japanese invasion, the indoctrination by Christian missionaries, and the in-migration of Christianized lowland groups, particularly the Ilocano and Tagalog. The mining and logging industries have destroyed the ecological systems in their territory, robbed them of their right to self-determination, and severely impaired their way of life.

Video: PCIJ documentary on Bugkalot tribe - An excerpt from the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism's documentary on various indigenous peoples of the Philippines. This excerpt deals with the Bugkalot, a former headhunting tribe, and their struggle to survive in the modern age - The documentary is called Katutubo: Memory of Dances.

Katutubo: Memory of Dances, 2001, directed by Antonio Jose Perez and produced by the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism, narrates the struggle of indigenous peoples to preserve a way of life that is being sacrificed for the sake of modern development. In the 1950s, the construction in Benguet of Ambuklao Dam displaced the Ibaloy and Ifugao from their ancestral land and drove them to Kasibu in Nueva Vizcaya, which was then Bugkalot territory. The three groups co-existed peacefully and their members eventually intermarried. Hence, when the national government unveiled plans to build a dam, the three groups, knowing it would destroy their sources of livelihood, united in protest. Their success did not, however, deter the government from later building a dam elsewhere, this time at the Casecnan watershed, which created another furor. The documentary ends with the groups facing another threat: large-scale mining. The film’s Bugkalot spokespersons stress that the land that provides boundless food is more important than the gold buried deep in the earth.

Nueva Vizcaya’s Tourism Office released in 2013 the province’s official promotional video Sama Sama sa Nueva Vizcaya, with music and lyrics by Marvin Babin Lim. The clip features some of the province’s food, festivities, and tourist spots, like the Capisaan Cave. Located at Malabing Valley at Kasibu, the cave is considered the country’s fifth longest cave system.

Sources:

Alarcon, Norma I. 1991. Philippine Architecture during the Pre-Spanish and Spanish Periods. Manila: University of Santo Tomas.

Alto-Paz, Milo, dir. 2000. The Headhunter’s Shadow. Written by Rosalie S. Matilac. Philippine Human Rights Information Center. VHS tape, 38 min.

Aquino, Dante M. 2003. “Community-based Forest Management for the Indigenous Peoples: Strengths and Pitfalls.” In The Sierra Madre Mountain Range: Global Relevance, Local Realities, edited by Jan van der Ploeg, Andres B. Masipiqueña, and Eileen C. Bernardo, 241-57. Cagayan Valley Program on Environment and Development (CVPED).

———. 2004. Resource Management in Ancestral Lands: The Bugkalots in Northeasern Luzon. Leiden: CML Institute of Environmental Sciences, Leiden University.

Barrows, David P. 1910. “The Ilongot or Ibilao of Luzon.”

The Popular Science Monthly 77 (36): 521-37.

Carlson, Sarah E. 2013. “From the Philippines to the Field Museum: A Study of Ilongot (Bugkalot) Personal Adornment.” Honors Projects Paper 45:1-59. http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/socanth honproj/45.

Cuasay, Pablo M. 1975. Kalinangan ng Ating mga Katutubo. Quezon City: Manlapaz Publishing Company.

De Asis, Jason. 2015. “Dam Operator California Energy Drying Up Casecnan River, Tribe Livelihood Affected—Bugkalot Leader.” Interaksyon, 15 February. http://www.interaksyon.com/article/105111/.

Department of Environment and Natural Resources. 2015. “The Capisaan Cave: A Geological and Spelunking Paradise in Nueva Vizcaya.” DENR.gov.ph. Accessed 21 August. http://www.denr.gov.ph/news-and-features/features/.

Diokno-Pascual, Maria Teresa, and Shalom MK Macli-ing (Freedom from Debt Coalition). 2002. “The Controversial Casecnan Project.”Export Credit Agencies (ECA) Watch. http://www.eca-watch.org/problems/asia_pacific/philippines/casecnan_fieldreport.pdf.

Domingo, Leander C. 2013. “Tribe Stakes Share in Local Power Project.” Manila Times, 7 September. http://www.manilatimes.net/.

Fox, James. 2006. “Austronesian Societies and Their Transformations.” In The Austronesians: Historical and Comparative Perspectives, edited by Peter Bellwood, James J. Fox, and Darrell Tryon, 229-43. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

Gatan, Fe Yolanda V. 1997. “Isang Durungawan sa Kasaysayang Lokal ng Nueva Vizcaya: Ang Nakaraan ng mga Isinay at Ilongot, 1591-1947.” MA thesis, University of the Philippines.

Gonzalez, Juan Carlos T. 2011. “Enumerating the Ethno-ornithological Importance of the Philippine Hornbills.” The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 24: 149-61.

Hendry, Robert S. 1959. Map. Manila: Philippine-Asean Publishers Inc.

Hoskins, Janet. 1996. “Introduction.” In Headhunting and the Social Imagination in Southeast Asia, edited by Janet Hoskins, 1-49. California: Stanford University Press.

IMDb. 2015. “FAMAS Awards for 1974.” IMDb.com, Inc. Accessed 10 June. http://www.imdb.com/event/ev0000232/1974.

Jenks, Albert Ernest. 1905. The Bontoc Igorot. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing.

Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2015. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 18th ed. Dallas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/18/.

Maramba, Roberto. 1998. Form and Splendor: Personal Adornment of Northern Luzon Ethnic Groups, Philippines. Makati City: The Bookmark, Inc.

National Geographic Magazine. 1912. (September).

Newson, Linda A. 2009. Conquest and Pestilence in the Early Spanish Philippines. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Notices of the Pagan Igorots in the Interior of the Island Manila. 1988. Translated by William H. Scott. Corporacion de PP. Dominicos de Filipinas Inc.

Orosa-Goquingco, Leonor. 1980. The Dances of the Emerald Isle. Quezon City: Ben-lor Publishers.

Perez, Antonio Jose, dir. 2001. Katutubo: Memory of Dances. Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism. DVD, 49 mins.