Bamboo Music: Pangkat Kawayan Orchestra, Banda Kawayan Pilipinas and PNU Himig Kawayan | Bamboo Musical Instruments [Video & History]

The “Pangkat Kawayan” (literally ‘Bamboo Band’) otherwise known as the “Singing Bamboo of the Philippines ” is a unique orchestra that draws music from unconventional bamboo instruments. This orchestra is composed of musically – talented students. The group’s musical instruments, numbering more than a hundred, are made of six genera of the versatile bamboo in various sizes, shapes and designs. Included are the bamboo tube or “bumbong,” the bamboo marimba or” “talungating,” the bamboo piano or “tipangklung,” the bamboo flute or “tulali,” the bamboo knockers or “kalatok,” and the bamboo musical rattles, the Philippine “angklung”. Completing the bamboo assortments are the drums, cymbals gong and triangle. The forte of this bamboo band is native Philippine songs, mostly folksongs from different regions of the country. However, the group’s repertoire also includes folk melodies from other countries, modern and popular music and some light classics.

The "Pangkat Kawayan" otherwise known as the "Singing Bamboos" of the Philippines is the first and only tuned-up "Musikong Bumbong" in the Philippines today. One can but proudly clam that this bamboo orchestra is most indigenous to our country and people. These instruments consists of the musical tubes or Bumbong, the native marimba or "Talunggating", the bamboo piano or "Tipangklung", the Moslem inspired native xylophone or "Gabang", the bamboo flute or "Tulali", the bamboo clapper or "Bungkaka", the bamboo knockers or "Kalatok". Completing the ensemble and adding flavor and rhythm to the music of Pangkat Kawayan are the non-bamboo instruments like the cymbals, bass and snare drums, gong,triangle and the Kulintang.

The Talunggating of four octaves and the Tipangklung of two and a half octaves produce the melody or the contrapuntal parts. The Bumbong which are chromatically scaled to two octaves and which produce standard tones compose the sustaining powers of the orchestra. These instruments are basically used to provide the harmony but may at times play the melody.

The forte of the orchestra is native Philippine airs mostly folk songs from the different regions of the country.

ABOUT THE VIDEO

Musika ng Kawayan: Yaman ng Bayan, A Virtual Concert

The "Musika ng Kawayan, Yaman ng Bayan" virtual concert is a showcase of Filipino talents, highlighting the use of local bamboo musical instruments (BMIs).

The event aims to promote the versatility of bamboo as an excellent and sustainable material for musical instruments, and feature the various BMIs used across the country.

The concert is organized under the "Bamboo Musical Instruments Innovation R&D Program" of the DOST-FPRDI, in partnership with UP Diliman, PNU, and DOST-PCIERRD.

Featured Bamboo Musical Instruments:

Among many others, the musical instruments which was featured in this concert include the bungkaka which creates a buzzing sound, the guitar-like kollitong, the nose flute tongali, the koratong bamboo tubes, percussion instruments such as tambi, patatag, marimba, and tongatong, as well as banduria, ukelele, and an organ all made of bamboo.

#PantugtogKawayan

#BambooMusicalInstruments

Bamboo Music, Wealth of the Town ′′ virtual concert - held November 27, 9-11 AM. Performed Online on DOST-FPRDI Facebook page.

Performances: Joey Ayala, Mr. Armando Salarza featuring Las Pinas Bamboo Organ, Bamboo Team, Dulag Karatong Festival Performers, Benicio Sokkong, Huni Ukulele, Dipolog Community Rondalla, and PNU Himig Bamboo. This is part of National Science and Technology Week celebration.

Pangkat Kawayan History

Pangkat Kawayan, also known as Singing Bamboos, was founded on 6 September 1966 at the Aurora A. Quezon Elementary School in Quezon City by Victor Toledo. It is a youth orchestra playing music on bamboo instruments. The original group, the first Pangkat Kawayan Company composed of 50 elementary school children, lasted for 13 years. In 1973, the second Pangkat Kawayan Company was organized, followed by the third in 1978, and the fourth in 1983. Each formation was retired as soon as 50 percent of the members reached the age of 24. At present, the group is composed of students in elementary, secondary, and college levels from Quezon City and Manila.

|

| Pangkat Kawayan at Aurora A. Quezon Elementary School, circa 1966 (Photo from Bambooman.com) |

The first musical pieces of Pangkat Kawayan consisted of Filipino folk melodies. It has developed a repertoire of traditional music, light classics, modern pieces, and popular music both Filipino and foreign. The group’s more than 100 instruments consist of various types of bamboo: the bumbong, a musical bamboo tube; talungating or bamboo marimba; tipangklung, a set of angklung (bamboo shakers) arranged as a horizontal keyboard, also known as “bamboo piano”; bamboo flute tulali; a bamboo clapper bungkaka; a bamboo knocker kalatok; xylophones gabbang; rattles alugtug; pipe diwdiwas; and Philippine angklung. Completing the orchestra are supplementary instruments such as drums, cymbals, gongs, triangles, and tambourines. Toledo designed the instruments, and he continues to manufacture new ones from bamboo and other materials.

Pangkat Kawayan has performed in many musical programs and entertained at national and international conferences. Its first performance abroad was at the World Expo '70 in Osaka, Japan. This was followed by performances in other world expositions and in international festivals. It played for “Balikbayan” performance tours in Hawaii and the West Coast in 1973, and in the United States mainland and Canada in 1974. In 1975, it was sent on official missions to Australia and Spain, and in 1978 to the People’s Republic of China. It also performed in the United States in 1982 and 1983.

The ensemble is led by Laura Gorospe, executive director; Elena Carlos, managing director; and Victor Toledo, musical director and conductor. It received the 2014 Manuel L. Quezon Gawad Parangal for the group’s vigorous promotion of bamboo music.

Banda Kawayan Pilipinas

Banda Kawayan Pilipinas (BKP, formerly called PUP Banda Kawayan) is a bamboo music ensemble based in the Polytechnic University of the Philippines (PUP) in Santa Mesa, Manila until 2013 after which it was registered in the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). The group had its first performance on 19 December 1973 in the Christmas party of the Philippine College of Commerce (PCC), which later became PUP. This was organized by the then principal of the school, Gloria R. Talastas, and by then professor of the same institution, Siegfredo B. Calabig, who has been its composer, arranger, trainer, and instrument maker. Instruments of the BKP are made of indigenous materials, mainly bamboo and narra. The ensemble consists of marimba, lira gabbang, bumbong, panpipes, and angklung. Other instruments, also made by Calabig, are the kalagong, kalatok, and kalavien, so named to carry the first two syllables of the instrument maker’s surname, “kala.” The group is now under the artistic direction of Rossini Calabig, the eldest son of Siegfred. Rossini has also assisted his father in the construction of instruments. Rossini’s cousin, Jaime Calabig, acts as the deputy musical director.

In 2014, in its desire to expand membership and pursue its mission and vision, the group was registered as a private, nonstock, nonprofit cultural organization with the SEC under the name Banda Kawayan Pilipinas. The group, no longer part of PUP, has 50 active members, comprising of high school and college students and young professionals. Senior members have assisted in the training of new members, some of whom join the group as early as at the age of 11. Junior members are taught the rudiments of playing the bamboo instruments, fundamental musical pieces, and basic choreography during their first year. They are gradually integrated through the years into the senior group. BKP’s repertoire is wide and consists of all-time local and international favorites that cater to all music enthusiasts. Their musical performance is spiced up with creative and lively choreography.

In its more than four decades of existence, the group has performed for state functions at Malacañan Palace, events organized by Department of Tourism (DOT), program of the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP), and in other public and private performances all over the country and abroad. The group’s first international performance was in 1988 at the World Exposition ‘88 and Australian Centennial held in Brisbane, Australia. The group was chosen to represent the country in the International Bamboo Festival in Oita and Beppu, Japan in 1998. They were also selected as the Best Performing Group in Busan International Trade Fair in South Korea in 2006 and in Kyonggi, South Korea International Travel Exposition. In the 14th Busan International Travel Fair, South Korea in 2011, they were given the recognition of the Best Folkloric Performance. BKP’s musical instruments and style have also brought them on concert tours in Europe, North America, Australia, Middle East and other Asian countries, to promote tourism and serve as the country’s ambassador of goodwill.

Some former members of BKP have become solo artists. These are Ely Aguilar, a freelance drummer and recording artist in Australia; Johann Calabig, a freelance drummer and recording artist in the United Kingdom; and Arnulfo Escobedo Jr., a vocalist and pianist of Milk and Money. In addition, BKP members have also organized and trained similar bamboo ensembles, namely, Banda Kawayan PUP in Lopez, Quezon and in Mariveles, Bataan; FEU Bamboo Band under Norberto Cads and Jemellette Tambot; Don Bosco School Laguna, Pampanga, and Cebu under Haydn Calabig, Frances Calabig, and Vernadette Pareno; Bamboo Ensemble, Filipino Community in Alberta, Canada under Herald and Heddy Casana; Bamboo Band in Honolulu, Hawaii under Rossini and Jaime Calabig; PUP Banda Kawayan, Calauan, Laguna under Benjie Andres; and the Bamboo Ensemble of South Cotabato under Bruce Espinas and Gian Gonzales.

Philippine Normal University Himig Kawayan

Philippine Normal University Himig Kawayan, also known as PNU Himig Kawayan, was organized in the 1990s by music education professor Pacita Narzo. The group was originally a rondalla class that is a requirement for majors in the bachelor of secondary education in music program at PNU. In 2001, the PNU Rondalla was formally recognized as an independent performing group in the said university. Shortly thereafter, it ventured into angklung ensemble playing. For a time, the same performers play for both the rondalla and angklung ensembles in PNU. Thus, the group was called the PNU Rondalla, Angklung and Ethnic Ensemble. A grant from the Japanese Cultural Center through Grant Assistance for Cultural Grassroots Project in 2007 made possible the separate organization of the PNU Angklung Ensemble. Consequently, the PNU Angklung Ensemble was renamed PNU Himig Kawayan in 2008.

An earlier grant from the UNESCO National Cultural Committee in 2003 and from Local Government Units bank rolled the group in organizing, training and monitoring of bamboo instrument ensembles in different localities in the Archipelago. The Philippine Society for Music Education (PSME) was also involved in the promotion of music by PNU Himig Kawayan to both local and foreign audiences.

Many opportunities paved the way for the transformations of the group. The grant from the Japan Foundation, the close ties with the PSME, and funding from the National Commission for Culture and the Arts defined the directions the group had taken. Funding gave the Himig Kawayan the capacity to build its collection of instruments. Institutional connections with the PSME and the NCCA gave it fora to perform in public and private spaces, and to give lectures on Philippine music.

Notable performances of the rondalla group included participation in the First (2004), Second (2007), and Third (2011) International Rondalla Festivals held in the Bicol region, and in the cities of Dumaguete and Tagum, respectively.

Aside from the many engagements to perform in various education-related activities, government functions and corporate events, the group regularly prepares for annual concerts. Previous concerts were titled Himig ng Lahi (Song of the Race), 2002; Kayamanan ng Lahi (Gems of the Race), 2003; Kabataan, Musika at Kinabukasan (Youth, Music, and the Future), 2006; Musika ng Lahing Pilipino (Music of the Filipino Race), 2009; Cuerdas sa Pagkakaisa (Strings of Unity), 2011; Kay Ganda ng Ating Musika (How Beautiful is Our Music), 2012; and Ngayon at Kailanman (Now and Forever), 2014.

Bamboo Music

The abundant year-round supply of the different species of bamboo and its inexpensiveness are reasons why Filipinos have found a variety of ways of using bamboo for construction, cooking, medicine, textile, paper, and music. As many as the number of different linguistic groups in the Philippines is the diversity of music instruments that the Filipinos have made out of the plant, and these instruments differ in terms of timbre (tone quality), name, manner by which sounds are generated from them, and significance in the lives of Filipinos.

Las Piñas Bamboo Organ - Musika ng Kawayan - Suite Cortesana - Pipe Organ Music

Indigenous Philippine bamboo instruments existed long before the Spaniards came to the Philippines. Bamboo music was heard during rituals, feasts, courtship scenes, work, and recreation. Bamboo music instruments can be classified into aerophones, idiophones, and chordophones.

Instruments that produce sounds when blown are called aerophones. Bamboo aerophones include various types of flutes, panpipes, and reed pipes, the most numerous found throughout the country being the paldong or palendag (vertical end-blown flute). The tongali (nose flute) is widespread in northern Philippines, but few are found in southern Philippines. It is played mostly by men and is used for serenading and courting, for quiet moments of relaxation, or for funerals. Flutes of Northern Luzon are tuned in pentatonic scales with or without semitones. The saggeypo, a type of stopped pipes, are aerophones found in the northern Kalinga. Used for entertainment by youth and adults, the saggeypo is also played while walking along mountain trails and may be played individually or as an ensemble. Meanwhile, the diwdiw-as (set of panpipes) found in Northern Philippines consists of open pipes that are tied together.

Idiophones produce sound when struck with an implement or with the hand. The source of vibration is the instrument itself. Bamboo idiophones in the Philippines are the xylophone, quill-shaped tubes, stamping tubes, scrapers, buzzers, clappers, and mouth harps. Bamboo tubes can be struck against each other, struck by sticks or mallets, stamped against hard objects, or shaken. The half-cut bamboo tongues in mouth harps (also called jew’s harps) are plucked. The mouth harp is found all over the Philippines and called by various names such as kulibao, ulibao, aribao, and kubing. The bunkaka (buzzers), tongatong (stamping tubes), and patang-ug (quill-shaped tubes) are prevalent among the Cordillera highlanders who use them for rites, celebrations, and entertainment. The patatag, a set of xylophone blades or staves, is used by the Kalinga children to learn the rhythmic patterns of the gangsa (gongs). The bamboo xylophone found in southern Philippines is called gabbang and kwintangan. The bamboo tubes with notches etched on the tube, which can only be found in southern Philippines, are called tagutok and kagul.

Chordophones are instruments that generate sound through the vibration of strings, either by plucking, striking, or bowing. A zither is an instrument with strings that run parallel to the length of its body. The body serves as a sound box or resonator. The zither has no neck, and the number of its strings varies. Zithers are found in northern Luzon, Mindanao, and Palawan. A common type is a bamboo tube whose strips are detached from its body but remain attached at both ends, with small bridges being inserted between the strips and the body. They are of two types: polychordal zithers with several strings that run around the tube and parallel-stringed zithers that usually have two strings on one side of the tube. Polychordal zithers are found in the Cordilleras, Mindanao, and Palawan, and are commonly called kudlung or kolitong. These are used for expressing human sentiments, for self-entertainment, for courtship, and for festive occasions as dance accompaniment.

The parallel-stringed tube zither has two to four strings that are plucked with the fingers or struck with small bamboo sticks. Boys and men play them for entertainment, with rhythms patterned after those played on the gongs. The bamboo half-tube zither among the Ifugao is called ayudding, and the paired string zither with slight variations found in northern and southern Philippines are called pasing, banban, tambi, kudlong, or takumbo.

Aside from its use in indigenous cultures, bamboo is also used to play Western music, as in the bamboo organ in Las Piñas, the musikong bumbong (bamboo wind instruments), the angklung (Indonesian bamboo ensemble), and other diatonically tuned instruments.

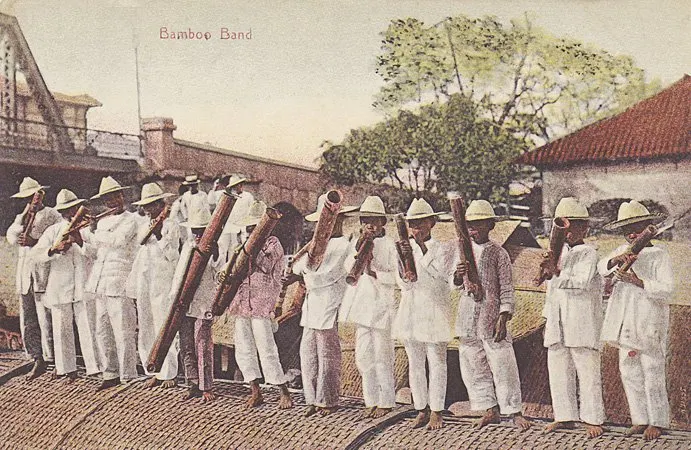

|

| Musikong bumbong, circa 1910 (Photo from Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The bamboo organ at Saint Joseph Parish Church in Las Piñas is considered a National Cultural Treasure. The instrument is the oldest bamboo pipe organ in the world. Fray Diego Cera de la Virgen del Carmen (1762-1834), a Spanish missionary, started to build the bamboo organ in 1816 with the help of the people of Las Piñas. Cera allegedly buried the bamboos that he used as organ pipes under the sand by the seashore for a year in order to wash out traces of sugar and starch in the wood and thus create tough, mature pipes. The organ was first heard in 1821 but without the horizontal trumpets. Cera completed the work in 1824 after deciding to use metal for the horizontal trumpets whose character of sound he could not get with bamboo resonators. For the general structure, native Philippine wood species, such as narra, molave, and kamagong, were used.

The bamboo organ measures 5.17 meters tall, 4.11 meters wide, and 1.45 meters deep. Hans Gerd Klais, who restored the organ in the mid-1970s, noted that the instrument contains a total of 1,031 pipes, of which 902 are of bamboo and 129 pipes are of metal. The pitch of each pipe is determined by its length. The organ has two unpitched accessory stops: the pajaritos and the tanbor, which produce the coloristic sounds of birds and the rumble of kettledrums, respectively. The Las Piñas Bamboo Organ is based on a typical Spanish baroque model, following the organ construction style of the era in which Cera lived. In 1978, the Bamboo Organ Foundation, a nonstock and nonprofit organization, was founded for the purpose of preserving the instrument. Since the bamboo organ’s return to the Philippines after its restoration in Germany in 1973-1975, annual concerts have been held at the Parish of Saint Joseph. The Diego Cera Organ Builders Inc, the first Filipino pipe organ building company, is specifically responsible for the maintenance and preservation of the bamboo organ.

|

| Las Piñas bamboo pipe organ, circa 1910 (Photo from Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The musikong bumbong is an ensemble of bamboo instruments that are reproductions of European band instruments. It flourished in the villages during the Philippine revolutionary period in the last quarter of the 19th century. The sound of each instrument, like the trumpet, trombone, horn, oboe, clarinet, saxophone, and sousaphone, is different from its original model because the instruments rely on the voice of the performers to produce the sounds. An instrument is open at both ends and has a hole on the side covered with a membrane, which produces a buzzing sound when the player hums rather than blows into the mouthpiece. Because it is not the instrument that produces the sound per se but the voice of the player, the band of such instruments is called banda de voca, which is literally “band of the mouth.” The air pressure produced by the hum makes the membrane vibrate, and the resulting sound varies in pitch and loudness with the player’s humming. The shape of the instrument helps amplify and project the sound.

The musikong bumbong proliferated in the villages, some organized by the Katipunero (Filipino revolutionaries) who fought against Spain in 1896-1898. These Katipunero used their musical talents to entertain their comrades, enlivening their unit’s activities by playing patriotic songs. Gathering as musicians and playing music also served to mask their secret meetings, according to accounts of their descendants who are at present members of musikong bumbong. Organized along the lines of the marching band, these all-bamboo ensembles were attempts by 19th-century Filipino nationalists and revolutionaries to create a uniquely Filipino sound. Through the years, the instrumentation of the musikong bumbong has evolved from the banda de voca to the inclusion of sound-producing bamboo instruments like the bamboo flute, bumbong (bamboo tube which at first looked like a sousaphone, but whose shape later on returned to straight bamboo tubes), clarinet, saxophone, trumpet, and trompas (French horn that sounded like the bumbong). This was the case with Malabon Musikong Bumbong. For the Obando Musikong Bumbong or Banda Santa Clara Musikong Bumbong, instrumentation has not changed much since its establishment. The group simply added sound-producing instruments like the harmonica, bamban (alto saxophone), cymbals, snare, and bass drums.

A possible offshoot of the musikong bumbong are the various bamboo ensembles that were organized during the late 1950s, which employed bamboo instruments tuned diatonically like the bumbong, talungating (bamboo marimba), tulali (bamboo flute), tipangklung (bamboo piano), and angklung. An idiophone, the angklung is an indigenous bamboo instrument popular in Java, Indonesia. It was copied in the Philippines also in the late 1950s when replicas were made by bamboo instrument maker Victor Toledo, who included it, among other bamboo instruments that he made, in the ensemble he founded called the Pangkat Kawayan or the “singing bamboos” of the Philippines. Other manufacturers followed suit. Also called alugtug or tugtug na paalog (played by shaking), angklung is played in groups, with each person playing an instrument traditionally in an interlocking or staccato manner. The angklung and the other diatonically tuned instruments, like the marimba, bumbong, talungating, tulali, tipangklung, angklung, mini tipangklung, lira gabbang, panpipes, chordal angklung, kalagong, kalatok, and kalavien, have been used in a variety of combinations by various bamboo ensembles all over the Philippines and in other countries as well, with repertoire varying from folk song, spiritual, modern to classical music for diverse occasions. Other manufacturers of bamboo instruments are Gilbert M. Ramos of Malabon Musikong Bumbong (now called Musikawayan) and Siegfredo B. Calabig of PUP Banda Kawayan (now called Banda Kawayan Pilipinas). The angklung is used in schools, universities, and the communities because the material is abundant and cheap. It is easily played by all ages and can be performed in any setting because of its interesting and beautiful sound. It may also be included in bamboo ensembles and other ensembles, like the rondalla (stringed instrument ensemble) and the orchestra. All these are factors for angklung’s wide acceptance and popularity in the Philippines.

Sources:

- Almario, Ani Rosa S., and Virgilio S. Almario. 2007. One Hundred One Filipino Icons. Manila: Adarna House and Bench.

- Almario, Virgilio S. 2002. Bulacan: Lalawigan ng Bayani at Bulaklak. Bulacan: Pamanang Bulacan Foundation.

- Anastacio, Rodrigo C. (bass drum player, trainer, instrument maker of Obando Musikong Bumbong). 2014. Interview by Pacita M. Narzo, 17 May.

- Bambooman [pseud]. 2014. “It’s All Bamboo.” Bamboo Music. Accessed 11 August. http://www.bambooman.com/bamboo_organ.php.

- British Broadcasting Corporation. 2014. “Origins and Development of Bamboo Music.” BBC. Accessed 4 August. http://www.bbc.co.uk/learningzone/clips/originsanddevelopment-of-bamboo-music/11926.html.

- Castro, Christi-Anne. 2011. Musical Renderings of the Philippine Nation. United Kingdom and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Center for Southeast Asian Studies. 2014. “Obando Fertility Rites.” Center for Southeast Asian Studies. Accessed 12 March. http://www.seasite.niu.edu/Tagalog/Cynthia/festivals/obando.htm.

- Corpuz, Onofre D. 2007. The Roots of the Filipino Nation, Vol 2. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Dioquino, Corazon C. 2014a. “Philippine Bamboo Instruments.” U.P. Diliman Journals Online. http://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/humanitiesdiliman/article/viewFile/1484/1439

- ———. 2014b. “Philippine Music Instruments.” National Commission for Culture and the Arts. Accessed 11 August. http://www.ncca.gov.ph/about-culture-andarts/articles-on-cn-a/article.php?i=155.

- Duldulao, Manuel D. 1987. The Filipinos: Portrait of a People. Quezon City: Oro Books.

- Filipino Biz. 2013a. “Philippine History, Interesting Trivia of Philippine History.” Filipino.biz.ph. http://filipino.biz.ph/culture/search.html

- ———. 2013b. “The Philippine Revolution: First Shots of the Revolution.” Filipino.biz.ph. http://filipino.biz.ph/history/trivia.html

- Guillermo, Artemio R. 2012. Historical Dictionary of the Philippines. Landham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press.

- Henares, Ivan. 2013. “Bulacan: Dancing at the Obando Fertility Rites.” Ivan About Town. http://www.ivanhenares.com/2007/05/obando-fertility-rites.html.

- Hila, Antonio C. 2014. “Indigenous Music.” Tuklas Sining: Essays on the Philippine Arts. Accessed 29 September. http://philippineculture.ph/filer/Indigenous-Music.pdf.

- Klais, Hans Gerd. 1977. The Bamboo Organ. Translated by Homer D. Blanchard. Ohio: The Praestant Press.

- Lakbay Pilipinas. 2008. “Sta. Clara Fertility Rites In Obando Bulacan Begins.” Lakbay Pilipinas. http://www.lakbaypilipinas.com/blog/2008/05/15/sta-clara-fertility-ritesin-obando-bulacan-begins/.

- ———. 2014. “Obando Fertility Rites: Fertility Dance, May 17-19/Obando, Bulacan.” Lakbay Pilipinas. http://www.lakbaypilipinas.com/festivals/obando_fertility_rites.html.

- Lauterwald, Helen Samson. 2006. The Bamboo Organ of Las Piñas. Las Piñas: The Bamboo Organ Foundation.

- Lopez, Mellie Leandicho. 2006. A Handbook of Philippine Folklore. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Maceda, Jose. 1998. Gongs and Bamboo: A Panorama of Philippine Music Instruments. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Manila Bulletin. 1998. “Concert at the Park presents ‘Ang Banda Noon at Ngayon.’” Manila Bulletin. Life and Leisure section, D-7, 30 May.

- Mañalac, Sheila. 2014. “Bamboo Organ Fest recovers lost Philippine colonial music.” The Manila Times, 25 January. http://www.manilatimes.net/bamboo-organ-fest-recovers-lostphilippine-colonial-music/70576/

- Mercurio, Philip Dominguez. 2014. “Bamboo Musical Instruments in the Philippines.” Pnoy and the City. http://www.pnoyandthecity.blogspot.com/#5b, 2007.

- Miller, George A. 1912. Interesting Manila, revised ed. Manila: E. C. McCullough & Co.

- New Tang Dynasty TV (NTDTV). 2013. “Bamboo Musicians: Philippines, Asian Brief.” YouTube. Accessed 2 December. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=74pks6lbc4k.

- Puerto, Luige A. del. 2006. “Bamboo Band Music Lives On, even in PNP.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 21 (4), 17 January.

- Pulumbarit, Veronica. 2013. “The Sounds of Bronze and Bamboo: Our Musical Heritage, and Why It’s Important.” GMA News Online, 9 October. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/

- story/330091/lifestyle/artandculture/the-sounds-of-bronzeand-bamboo-our-musical-heritage-and-why-it-important.

- Quirino, Carlos. 1995. Who’s Who in Philippine History. Manila: Tahanan Books.

- Ramirez, A. “Traditional and Cultural Uses of Bamboo, Ang Kawayan,” from the proceedings of the First National Conference on Bamboo, CITC, Manila, Philippines, 1999. p. 7. http://www.pcaarrd.dost.gov.ph/home/momentum/bamboo/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=1296:philippine-bamboo-musicalinstruments&catid=118&Itemi.

- Ramos, Gilbert M. (conductor and musical director of Malabon Musikong Bumbong). 2014. Interview by Pacita M. Narzo, 28 March 29, April, 7 May, and 22 May.

- Reyes-Urtula, Lucrecia, and Prosperidad Arandez. 1992. Sayaw: An Essay on the Spanish Influence on Philippine Dance. Manila: Sentrong Pangkultura ng Pilipinas.

- Rivera Mirano, Elena. 1992a. “Musicians and Musical Group.” Musika: An Essay On The Spanish Influence On Philippine Music. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines.

- ———. 1992b. Musika: An Essay on the Spanish Influence on Philippine Music. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines.

- ———. 1992c. Musika III: A Documentary and Essay on the Spanish Influence on Philippine Music. Documentary directed by Lito Tiongson. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines.

- ———. 1994. “Philippine Music.” CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art, Vol 6. Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines.

- Roces, Alfredo R. 1977a. Filipino Heritage: The Metal Age in the Philippines. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc.

- ———. 1977b. “Tinggian Music is a Total Experience.” In Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, edited by Alfredo R. Roces, Vol 2. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc.

- Roxas-Wi, Corazon et al. 2006. Obando: Bayang Pinagpala. Bulacan: Obando Local Government.

- Santiago, Maximo C. (musician and former president of Obando Musikong Bumbong). 2014. Interview by Pacita M. Narzo, 28 March, 4 April, and 29 April.

- Siojo, Ron. 2014. “Philippines: The Bamboo Organ of Las Pinas and It’s Builder.” Knoji Consumer Knowledge. http://philippines.knoji.com/philippines-the-bamboo-organ-oflas-pinas-and-its-builder/.

- TxtMania. 2013. “Bulacan Province, The Land of Bulakeños or Bulakenyos.” TxTMania. http://www.txtmania.com/articles/bulacan.php.

- Watawat. 2013. “The Republic of Real De Kakarong De Sili.” Watawat. http://www.watawat.net/ _the_republic_of_real_de_kakarong_de_sili.html.

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?