Storage Jars & Musket Balls & Other Treasures Found in the San Diego Shipwreck Near Fortune Island in Batangas, Philippines [Amazing Archeology]

San Diego was a Manila galleon engaged in inter-island trade, hastily converted into a warship along with two other vessels to engage a Dutch naval fleet that entered Philippine waters. The vessel sank on 14 December 1600 near Fortune Island in Batangas, after defeat by the Dutch ship Mauritius.

Also check out previous posts that narrate the story of the San Diego Shipwreck and some of its archaeological assemblage (Japanese Sword Found in the San Diego Shipwreck)

Recovered from the shipwreck are more than 800 earthenware and stoneware storage jars from China, Thailand, Myanmar, and the Iberian Peninsula in Europe, highlighting the thriving maritime networks between Asia and the Americas during the late 16th century CE. It also reflects the disorganized loading system as new jars that may have catered to the passengers of high status were added to the large, utilitarian jars that were used for trade. Interestingly, some of the jars have alphanumerical marks possibly denoting ownership.

The Chinese jars were of at least four types: Tradescant jars, dragon jars, luted jars, and plain and undecorated jars. The Tradescant jar takes after John Tradescant, a botanist who died in 1638 and whose ceramic collection is at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, England. These jars have distinct green and yellow glazes with relief floral decorations. The dragon jars are generally large, glazed stoneware jars with impressed dragon decorations. Majority of the dragon jars come from the kilns in Guangdong and Fujian Province.

The luted jars are large, generally black-glazed plain jars with a concave base and four horizontal ears. A distinct process creates the jars, as this involve the joining of two separate parts, one part from the rim to the upper neck while the other part from the upper neck to the base. There was also a number of plain, unglazed jars with four ears and wide shoulders that tapers to a small base.

The Martaban jars are large jars that have dark red stoneware bodies covered by a generally black glaze. The decoration is made of light-colored clay in low relief, either of stripes or rows of buttons resembling rivet heads. This type of jar is a specific name designating exclusively a class of ceramic jars produced in Lower Myanmar (formerly Burma), dispelling the previously known term Martaban jars that connote large Asian storage jars.

The Thai jars are large ovoid jars with wide, short necks with round everted rim, narrow short necks with a round lip, high necks and trumpet-like mouth rims or having long necks with large everted rims. The Mae Nam Noi kilns at Bang Rachan district, Singburi province in central Thailand produce these types of jars.

The jars from the Iberian Peninsula are generally termed Spanish olive jars and may have been loaded from Mexico. These jars have oval, amphora-like shapes that have round bottoms and are mostly arranged in layers, laid side-by-side on a bed of straw or hemp fiber and separated by pieces of wood. The absence of an ear and a neck and the thick edge of the opening gives the impression of an unsophisticated appearance.

Spanish Olive Jars

More than 34,000 archaeological objects have been recovered from the shipwreck, including at least 16 Spanish olive jars. These are earthenware characterized by coarse, unglazed fabric in oval, amphora-like shapes with thick, narrow rims and rounded bottoms.

The term “olive jar” derives from its early purpose as containers for olives and olive oil, but has then evolved to contain many other substances such as water, wine, food items, and even construction materials. Seville and Cadiz in Spain produced the jars from the 16th to the 18th centuries Common Era or CE. These were considered a continuation of the Mediterranean amphora tradition that began in the early centuries CE.

Galleons from Spain to Acapulco, Mexico via the Atlantic Ocean may have carried the San Diego olive jars. From Acapulco, the jars were transported across the Pacific Ocean to the Philippines in a Manila galleon, not the San Diego, as the vessel reportedly only plied the inter-island route. Its presence in the vessel may be attributed to the Spanish merchants and passengers, who were on board when it sank. These jars represent the only examples found in Philippine archaeological context, and are thus significant material evidence of the maritime connection between the Philippines and Spain.

Ceramic finds of the wreck

San Diego was a Spanish trading ship converted into a warship that sunk in December 14, 1600 after a naval battle with the Dutch vessel Mauritius off the waters of Fortune Island, Batangas at a depth of more than 50 meters below sea level. In 1992 and 1993, the shipwreck was excavated by World Wide First (WWF) led by French underwater archaeologist Franck Goddio in collaboration with archaeologists of the #NationalMuseumPH. The recoveries yielded more than 34,000 archaeological materials. One of the notable finds in the cargo are the earthenware with porcelain inlaid designs.

Earthenware vessels played an important role in the preparation, transport, and preservation of foods and drinks in Southeast Asia. The pieces found in San Diego have unusual decorations. Some of the jars and oil lamps were decorated with small fragments of porcelains around the body. These small earthenware pieces were likely manufactured in the Philippines as they reportedly share similarities with the pieces found at the Santa Ana archaeological site in Manila. Along with the inlaid porcelains, the two-eared jars were have engraved lines and grooves as decorations.

The oil lamps are remarkable pieces with a basket-shaped appearance and having four arms joined at the top where they were suspended. From the accounts, these oil lamps were reserved for the ship’s common interior spaces. Moreover, the use of lamps on board were strictly monitored and controlled to prevent the risk of fire on board. The unique designs found on the vessels are evidence of innovation from the work of local craftsmen by introducing new elements with the traditional decorations. In fact, most of the earthenware pieces on San Diego were copies or imitations of European vessel shapes made of glass, tin, or silver.

These earthenware jars and oil lamps are currently displayed on the San Diego Gallery at the National Museum of Anthropology. As we wait for our #NationalMuseumPH to open again, we encourage you to #StaySafeAtHome and enjoy our #MuseumFromHome programs.

Round bullets or musket balls from San Diego Shipwreck

San Diego is a Manila galleon converted into a warship that sank in 14 December 1600 near Fortune Island, Batangas, after a naval battle with the Dutch ship Mauritius.

Musket balls or round lead projectiles were used in most muzzle-loading rifles, and nearly all-black powder pistols and cap and ball revolvers from the 13th to 19th centuries Common Era (CE).

These bullets became essential during Europe’s incessant territorial and trade wars in the 16th and 17th centuries. Their usage continued even after the conical hollowed-out bottom bullets became famous in the early 19th century. Small musket balls were once made by cutting the lead sheet into cubes and then rounding off the corners, either by rubbing with a wooden board or tumbling in a barrel. However, spherical lead balls were best produced with molders brought by soldiers in the battlefield. The residues from the burning gunpowder normally foul up the barrel, making loading difficult; thus, it is important to cast the bullets slightly smaller in diameter than the bore of the gun to avoid this problem.

Thousands of pieces of musket balls were among the significant finds during the archaeological excavations of the San Diego shipwreck by the World Wide First (WWF) and the #NationalMuseumPH in 1992 and 1993. The projectiles, mostly casted from lead materials except maybe for a few corroded pieces, are of various sizes ranging from approximately 0.46 to 0.94 inches (1.17 to 2.39 cm) in diameter. Most of these shots were fired from .69in to .75in caliber Spanish service muskets, and .71in caliber Spanish cavalry pistols. The smaller bullets may fit as projectiles for harquebusiers while the larger ones were used as projectiles for higher caliber firearms.

Interestingly, these small round lead projectiles are currently not considered as deadly bullets. However, archaeological evidence revealed that musket balls were capable of lethal impacts. In his catalogs, British army surgeon Dr. Charles Bell, documented the effects of musket balls shot on the human body during the Battle of Waterloo in 1815. Burial and skeletal remains of soldiers, who died and/or were injured during the battle, were seen with tremendous damage caused by musket balls.

Copper Morións or Helmets

The morións from San Diego shipwreck measures approximately 21 cm high and 27 cm in diameter, and weighs about 2–3 kg. The copper helmets’ shape is similar to an inverted basket, with high peaks and edges, leaving the face uncovered. Morións developed in Spain during the 15th century Common Era (CE), and later spread throughout the Spanish colonies in the mid-16th century CE, worn by foot soldiers, pike bearers, and arquebusiers. In France, the honor guards, light cavalry, mounted arquebusiers, and “pistoliers” use similar morións.

Interestingly, the earliest form of armor was probably from animal hides, leather, and cotton. For instance, ancient Egyptians from the 3rd century CE wore crocodile skin-helmets, believing that they would take on the strength and the attributes of that fearsome creature. The earliest laminated iron helmets in China appeared during the Later Han Dynasty period (25–220 CE) while the Greek hoplites or armed men from the 7th century CE wore bronze helmets.

Terracotta Ceramics

Terracotta (or “baked earth” in Italian language and a type of earthenware) are ceramics fired to temperature of less than 900 OC and generally characterized as coarse, porous, and usually colored red. Some examples of terracotta found in Philippine archaeological sites include the Maitum secondary burial jars in Sarangani Province dated to the Philippine Metal Age (500 Before Common Era–370 Common Era, or CE) and the Manila Ware dated to the 16th– 19th centuries CE. They come in different shapes and sizes, and are used for a variety of purposes.

Out of more than 34,000 artefacts, only two are terracotta pieces from Mexico have been found in the San Diego: a pitcher and an ewer. The table pitcher has a spherical belly, bell mouth, handle on the spine, pouring spout, and decorated with flowers, leaves, vines, and stem in a spiral painted in a continuous pattern on the belly and neck. The ewer, on the other hand, has an anthropomorphic head, globular body bridge handle, and tubular spout. Both pieces were produced in Mexico but the shape and decoration may have been influenced by European ceramics. The pitcher bears similarity with the Majolica ware of Spain, while the ewer head and hairstyle resembles European features.

These pieces are significant as it shows the combination of European influence and Latin American craftsmanship on board a Manila Galleon based in the Philippines. This reveals the cultural impact of a conquering or dominant political power on the work of local craftsmen as seen by the subtle mixing of new elements with traditional shapes and decorations.

The Advent of Gunpowder

Gunpowder is a mechanical mixture of saltpeter, sulfur, and coal. The Chinese alchemists during the Song Dynasty period (960–1279) discovered gunpowder initially to transform metals and as an elixir for immortality. The mixing of the three elements produced mystical effects such as crackling sounds and mesmerizing light display. The invention eventually led to the emergence of pyrotechnics and the manufacture of fireworks believed to frighten evil spirits.

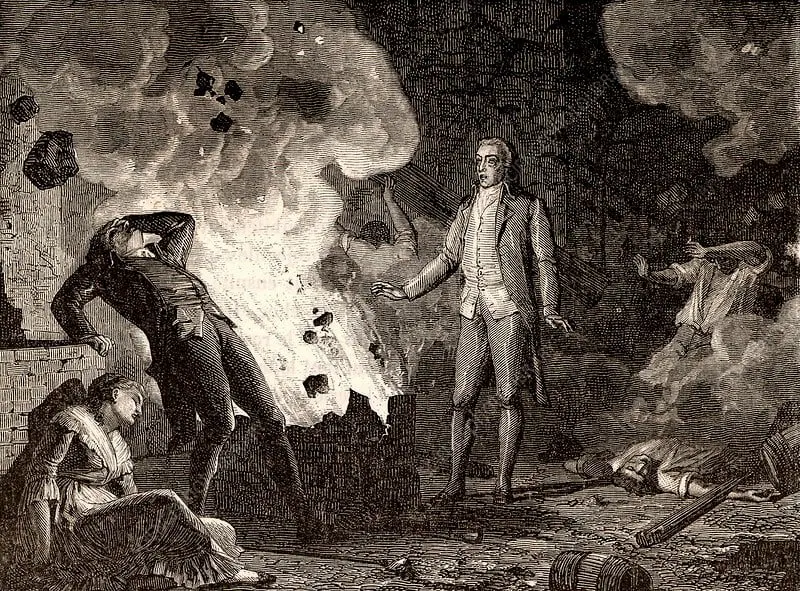

|

| An engraving from Les Merveilles de la Science by Louis Figuier (Paris, c.1870) of the infamous Berthollet’s gunpowder unfortunate experiment that had fatal results. Copyright © UNIVERSAL HISTORY ARCHIVE / UIG / SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY Image Source: https://rb.gy/nd6lki |

More ingredients were later added that produced bigger explosions, paving the way for the emergence of early artillery shells, bombs, and other different explosive mixtures. Elsewhere, the gunpowder development shaped up war tactics and military technology. The Europeans, for instance, were swift to adopt gunpowder technology and tested it in the battlefield.

|

| Repercussions of the discovery of gunpowder – War became explosively deadly. Image from the book cover of Tonio Andrade’s “The Gunpowder Age” (2016). |

|

| An example of similar gunpowder jar, reinforced with metals for storage and logistics purposes. Image Source: https://bit.ly/378Z4Ck |

Glazed stoneware jars, especially those manufactured in China remains the most efficient means of packaging for the transport of fragile or valuable merchandise. Jars also contained liquid materials such as water and oil as well as gum, rice, sulfur, and powder based on shipwreck evidence. Some glazed jars from San Diego were used to store gunpowder.

Chain shot artillery projectiles

Chain shots are projectiles generally used against enemy ships during war at sea. Along with crossbar shots, chain shots are specifically designed to spin in flight to destroy the enemy ships’ rigging (sails, masts, booms, yards, stays, and lines), and cause de-masting and demobilization of the ships.

|

| An example of a half-balls chain shot for cannons. Image Source: https://bit.ly/hbchainshots © Open Access Image under Creative Commons Zero (CC0) |

Chain shots comprised mainly of two or more iron or lead cannonballs, half-sphere, or hollowed cannonballs attached by a short-length metal chain. When fired, the inertia of the balls pulls them away from one another, creating a whirling bolas that tears through the enemy ship’s rigging. Chain shots are usually fired upward the enemy ship’s sails and scythe down enemy crews on the upper decks, creating opportunities for easy boarding.

|

| Speculative 3D assembly of chain shots from San Diego shipwreck. © NMP-MUCHD |

The archaeological excavation of San Diego shipwreck by the #NationalMuseumPH in collaboration with Franck Goddio’s World Wide First (WWF) in 1992 yielded 14 cannons and other smaller arms and artilleries, along with thousands of archaeological objects. Among these are cannonballs cast from iron and lead as well as those carved from stones, a lead bombshell and a bar shot, and chain shots.

Chain shots were half-balls cast from lead ranging approximately from 8.1–9.2 cm. Iron concretions on those were indicative of the corroded iron chains that used to connect the half-spheres. Only 2 of the 4 half-spheres are of the same diameter.

Interestingly, while chain shots were deemed effective against the galleys and galleons, as well as the bigger and faster clipper ships, the advent in the 19th century of steam-powered ships that do not require sails and masts has rendered chain shots obsolete.

____________

Archaeological study is very important in supporting accurate interpretation of past events, which helps in reconstructing our history. When a site is disturbed or pilfered, we lose information forever without the significant context to assist us in piecing together our story. This is much more valuable than the selfish individual’s monetary gain or enriching their personal collections.

Our heritage and recounting its narrative through material culture benefits future generations and our aspirations as a nation. If you see or have knowledge of sites being looted, report to your local government authorities immediately or contact the closest NMP office near you.

Your #NationalMuseumPH has opened to the public with tours still suspended. In the meantime, know more about our collections through our galleries and this series, and expect an upgraded exhibition on three centuries of maritime trade soon.

________________

Poster, text and photos by the Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division

Images © Frederic Osada, Gilbert Fournier, Franck Goddio/World Wide First (WWF)

© National Museum of the Philippines 2021

![San Diego Shipwreck Near Fortune Island in Batangas, Philippines [Amazing Archeology] San Diego Shipwreck Near Fortune Island in Batangas, Philippines [Amazing Archeology]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgxIaSuubYh4vEXyaK7qSH8w2hnsgus995m8W0J87lfuCd2ZcZDLC2X8nSmqXTN8SDFQrZtZUAP9dr7ZsxuUg5KUK1Ki_0p1HVtjwexBxne_m4d0W6tk5IezIDHNqakKr7dnyfd/s16000-rw/233590866_4544851548872461_3328020178313009623_n.jpg)

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?