Microfossils: A Closer Look at the Archaeological Relevance of Plant Remains [Paleoethnobotany | Archaeobotany]

Artifacts and associated features immediately come to mind when we think of an archaeological site. However, in archaeological excavations, organic and environmental materials like animal and plant remains, are almost always recovered. We have previously introduced the relevance of studying animal remains from archaeological sites (known as zooarchaeology) by featuring micromammals.

Paleoethnobotany or archaeobotany is the study of plant remains found in archaeological contexts. Plants give a wealth of information on the palaeoenvironments (past environments) and past human activities. Some of the plant materials studied from archaeological contexts are microbotanicals like pollen, spores and phytoliths.

These remains are not visible to the naked eye; thus, their analysis involve a set of procedures that include recovery and microscopic examination. They provide data on past environments and climate reconstructions, plant utilization and domestication, and subsistence strategies. When recovered from stone tools and teeth, these microbotanical remains can be direct evidence of plant use and diet, respectively.

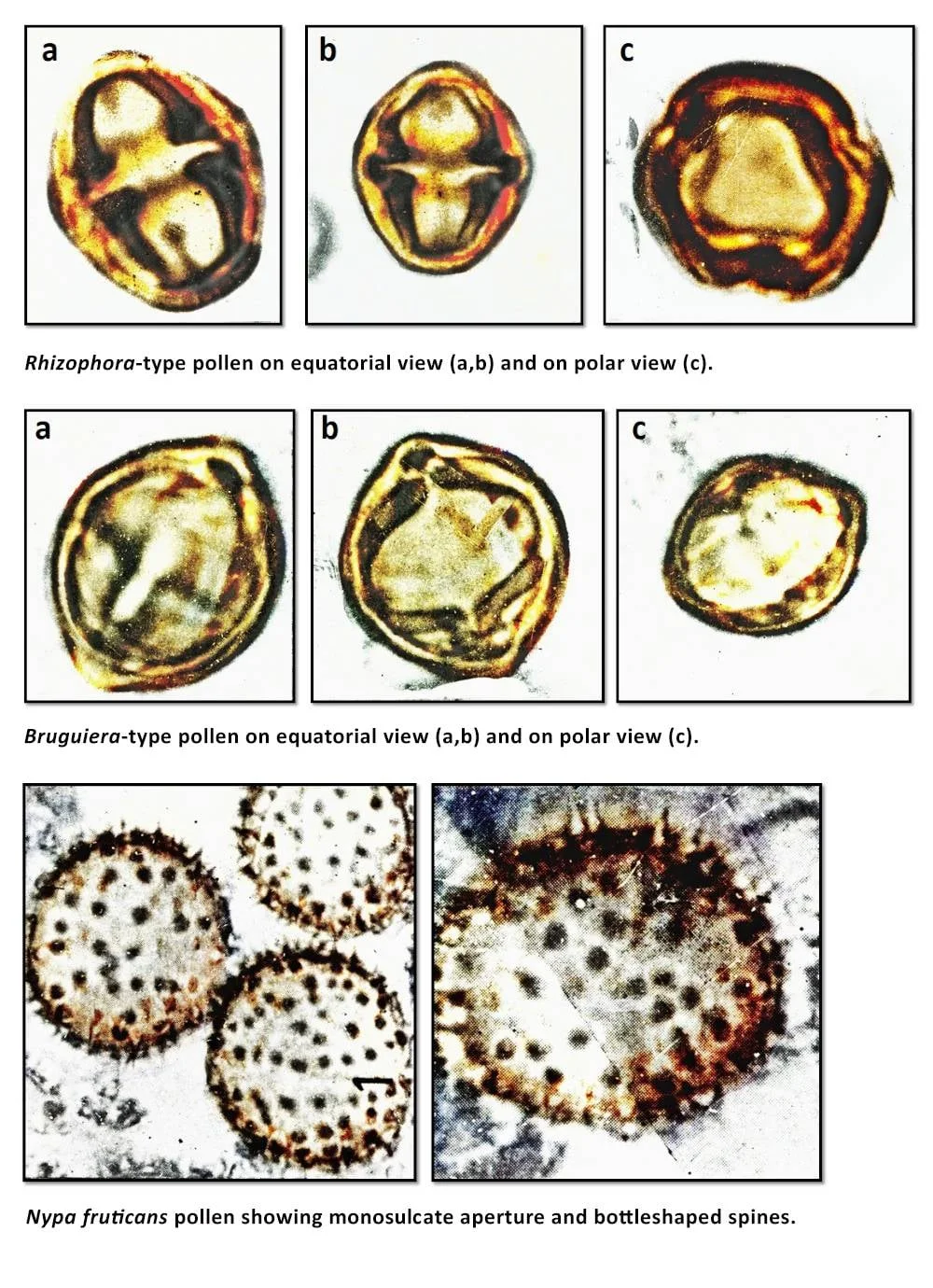

Palynology involves the study of pollens and spores (palynomorphs). Pollens appear as powdery substance in flowers of angiosperms (flowering plants) and cones of gymnosperms (cone-bearing plants). Spores, on the other hand, are produced by lower plants (collectively called cryptogams) such as ferns, mosses and liverworts. Both pollens and spores are necessary in plant reproduction. These organic materials have relatively good preservation in sediments due to their tough outer layer called exine.

In the 1980s, Dr. Lolita Bulalacao, Scientist II and former researcher at the National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) analyzed pollens from sediment cores sampled in the area surrounding the Tabon Cave complex to reconstruct the palaeoenvironment contemporaneous with the famous Tabon skull cap. Her findings indicate that the previous local vegetation around the Tabon Caves was an “extensive mangrove belt”, preventing its prehistoric inhabitants to fish in the open sea waters. She concluded that they were food gatherers rather than fisher folks. Dr. Bulalacao was the first Filipino palynologist to study pollens from archaeological sediments, and established the palynology section of the NMP Botany and National Herbarium Division (BNHD).

|

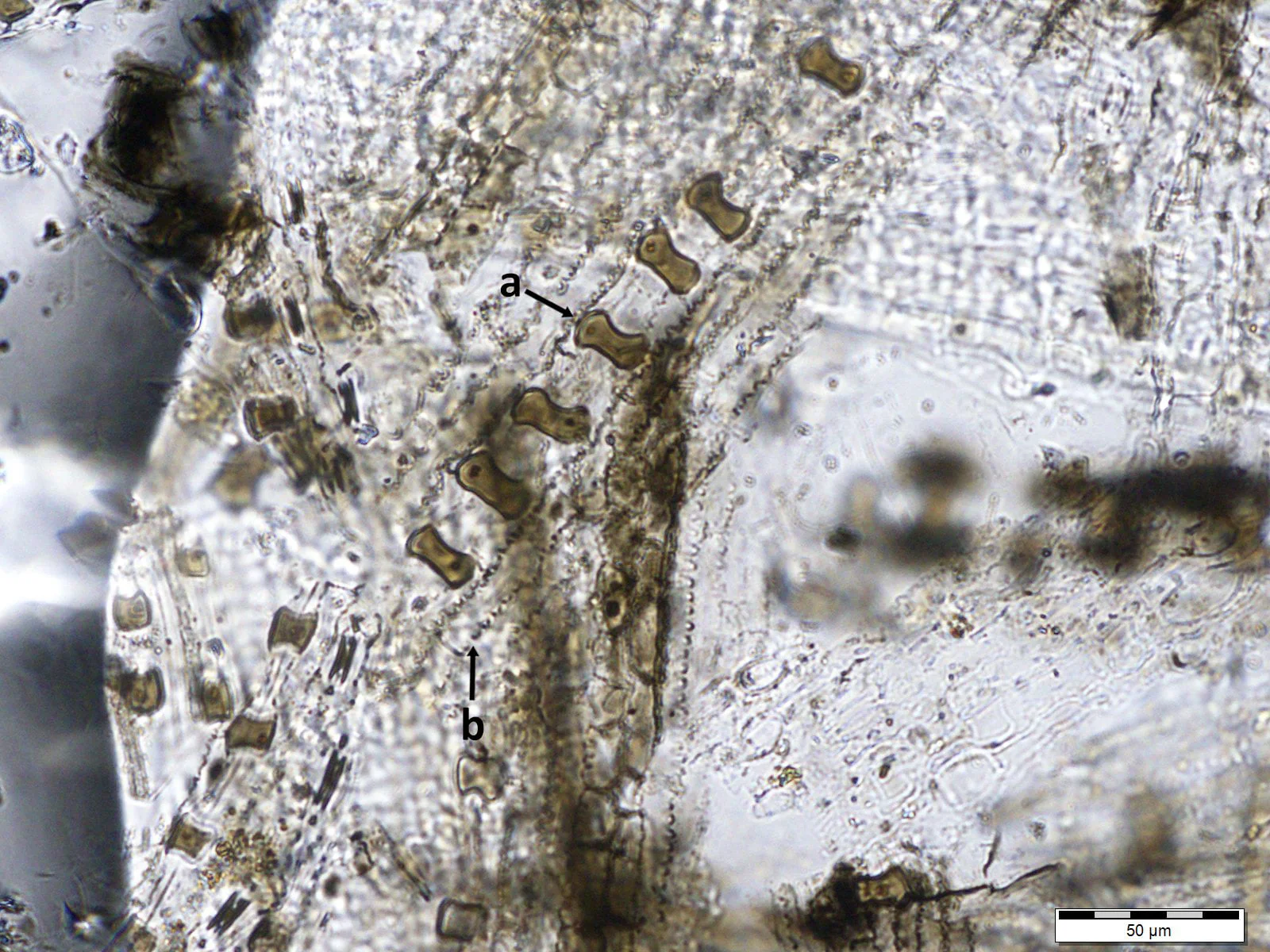

| Phytoliths from bamboo (Phyllostachis nigra)leaf showing two general morphotypes: (a) dumbbell type and (b) elongate type. |

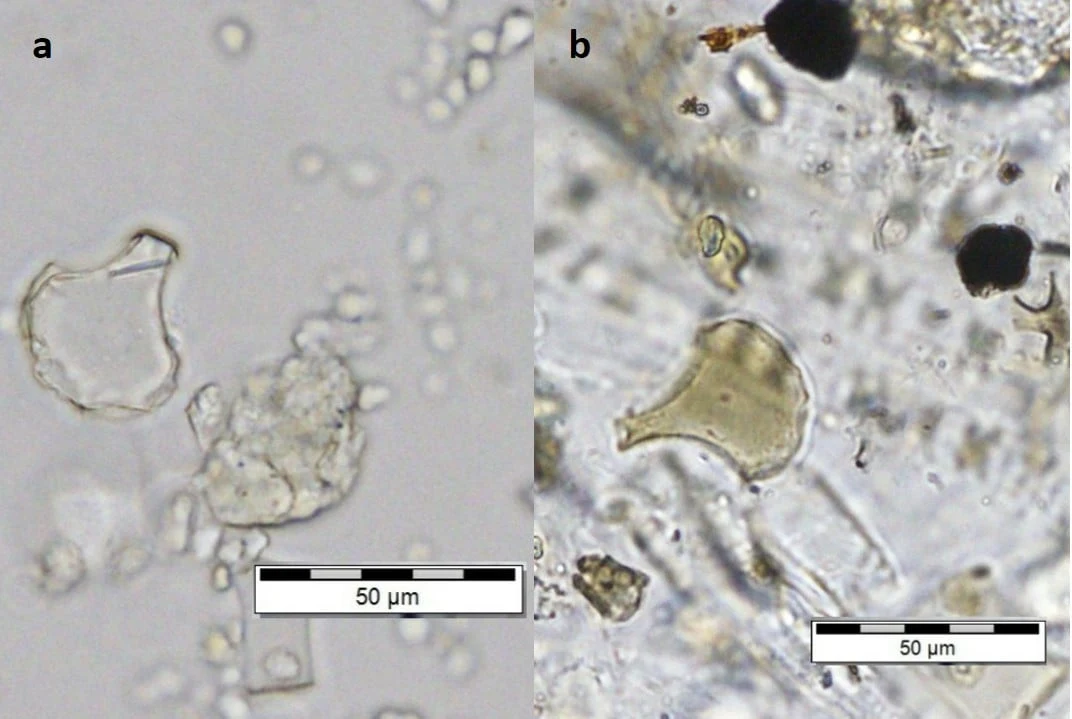

Phytoliths are plant cell casts made of silica. These plant materials are widely distributed in living plants, occurring in the stem, leaf, flower and fruit. Their exact function is still unknown, although it is believed that these rigid cells provide mechanical support for the plants and act as deterrent to predators.

Like pollens and spores, phytoliths are very resistant to decay and preserve well in sediments due to their inorganic silica composition. While pollen can be distributed widely via wind and water dispersal, phytolith requires the deposition of the actual plant or its parts in the immediate environment, thereby reflecting localized flora or vegetation—a characteristic that is very helpful in reconstructing the past environment specific to the site.

Analyses and interpretations of phytoliths tend to be tedious; different plant groups or taxa may produce similar-looking phytoliths, while a single plant may produce several phytolith forms, depending on the plant part deposited in the sediment. Phytolith analysis is still at its pioneering stage compared to palynology. Dr. Victor Paz, professor at the University of the Philippines-Archaeological Studies Program, who made major contributions in the archaeobotanical literature of the country, has listed six archaeological sites in northern Philippines that were analyzed for phytoliths. Some of the phytoliths recovered are from grasses, legumes and amaranth.

In a study in 2018 that is part of the Ifugao Archaeological Program, Drs. Mark Horrocks, Stephen Acabado and John Peterson investigated the possible past agricultural practices in the Old Kiyyangan Site in Ifugao by analyzing the microbotanical remains from the sediments within the site. Based on the rice phytoliths recovered, it was suggested that rice cultivation was practiced as early as 1275 CE (Common Era) and intensified around 1600 CE.

Palynological study of the organic-rich sediment containing minute charcoals revealed the abundance of grass pollen and fern spores, followed by moderate amount of sedge pollens. The presence of these palynomorphs in the assemblage suggests a wet or damp environment suitable for rice cultivation. The same organic-rich sediment was also sampled for dating and it was inferred that human-induced modification to the environment, such as forest clearing, likely occurred at the site as early as 1140 to 1275 CE.

Archaeobotany is still a developing field in the Philippines yet archaeological projects in some sites in Mindoro, Palawan and Lal-lo in Cagayan Valley, regularly incorporate plant remains extraction as part of fieldwork activities.

A pottery sherd embedded with visible plant remains recovered from Andarayan Site in Cagayan Valley is currently exhibited at the Rice, Biodiversity and Climate Change Gallery in the National Museum of Anthropology. The pottery inclusions, in the form of carbonized rice glume, husk and stem, were dated 1575–1325 Before Common Era (BCE)–the oldest evidence of rice in the country.

The #NationalMuseumPH has recently opened to the public and we look forward to welcoming you in our galleries to show you these and other artifacts recovered from archaeological excavations.

_________________

Text and photos by Maricar B. Belarmino, and poster by Timothy James Vitales / NMP Archaeology Division

Additional images by M. Belarmino and R. Episcope

©️ National Museum of the Philippines (2021)

![Microfossils: A Closer Look at the Archaeological Relevance of Plant Remains | [Paleoethnobotany | Archaeobotany] Microfossils: A Closer Look at the Archaeological Relevance of Plant Remains | [Paleoethnobotany | Archaeobotany]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEh6c-Rx7TnXV-LnRHmOg_Yn7bHmvZxer-K83qSi2dfcXeJDVRkuhvb7UL8oMi4GpeoqkbYUkACTUV24lGPf-odNxi21D-XlRBgdhSqaetWWZ0mPep_OSFoJNfsFPfDlnnfQ5nc1/w640-h522-rw/158451002_4088348987856055_2008877360060585939_o.jpg)

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?