Pandanan Shipwreck - Amazing Archeological Finds [Pandanan Island Coast of Southern Palawan]

Porcelain Blue and White Bowl

In 1993, the Pandanan shipwreck was accidentally discovered by a pearl farm diver while looking for a missing basket containing pearls near Pandanan Island, southern Palawan. Two years later, the site was archaeologically excavated and yielded remains of a wooden ship that contained over 4,000 various objects from different countries.

The shipwreck is a merchant vessel of possibly Southeast Asian origins based on its cargo. Vietnamese ceramics from the north and central region of Vietnam comprised more than 70% of the ceramic cargo along with lesser quantities of Chinese and Thai ceramics as well as undetermined earthenware pots and stove. The non-ceramic items comprised glass beads, iron cauldrons, bronze gongs, small guns, a bronze weighing scale as well as other natural and manufactured products. A Chinese coin dated to the reign of Chinese emperor Yongle (1402–1424) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) that provided the basis of the relative dating of the site.

The porcelain blue and white big bowl is very remarkable in that it has been manufactured in the 14th century during the short reign of the Mongolian-led Yuan Dynasty period (1279 – 1368), almost 100 years before the Pandanan vessel sailed in the middle of the 15th century. This period also saw the earliest mass production of porcelain blue and white ceramics, specifically during the years 1328 – 1352, making Yuan dynasty ceramics very rare due to its very narrow production and export period.

The bowl has also a very remarkable decorations. The central design depicts two fabled beasts, the qilin (tɕʰǐ. lǐn or kî-lîn in Hokkien) and the phoenix, both very important motifs in Chinese mythology. The qilin, also known as a unicorn or a dragon horse, is perceived as the noblest of hairy animals and symbolized perfection. It is also a portent of benevolent government. The phoenix on the other hand, is a sacred bird and believed to be the king of all birds that symbolizes good fortune, the sun, fertility, abundant harvest, good luck and longevity.

Why was a 14th century bowl found in a 15th century ship? Archaeologists and scholars speculate that the bowl may have been a merchant’s heirloom piece and used as a trading commodity in exchange for Southeast Asian luxury goods. Another theory is that the bowl, along with other unique ceramics, were used as a tribute to a king or a ruler in order to ask permission to carry out trade activities. The blue and white bowl and the rest of the archaeological assemblage of the Pandanan shipwreck proves that the Philippines has been an active participant in international trade during the 15th century.

______________

Text poster by Bobby Orillaneda, Poster by Nero Austero/NMP MUCHD

©National Museum of the Philippines (2020)

Champa Ceramics

|

| Another Champa kiln site |

Indo-Pacific Beads

In 1993, the site was accidentally discovered by a pearl farm diver looking for a missing basket of pearls near Pandanan Island in southern Palawan. Two years later, archaeological excavations by the #NationalMuseumPH in collaboration with the Ecofarm Systems, Inc. led to the recovery of glass beads along with 15th century CE (Common Era) Vietnamese, Thai, and Chinese ceramics. The glass beads were found encrusted with corals inside many Vietnamese stoneware jars.

|

| Indo-Pacific beads from various sources. (Image from the 2002 publication by Peter Francis “Asia's maritime bead trade: 300 BC to the present”) |

Indo-Pacific beads were the most common and widely traded beads in precolonial maritime Southeast Asia. The term “Indo-Pacific beads” was coined by Peter Francis to define the beads’ color, material, geographic distribution, and manufacturing technique. Usually less than 6 mm, these glass beads comes in colors of monochrome opaque red, black, white, green, yellow, as well as translucent blue, green, and violet. They are undecorated and usually in cylindrical or oblate shapes. These glass beads are made by drawing out a thin tube from a hollow globe of molten glass then cooled. The glass tube is then broken into smaller individual beads.

|

| Excavation on the Pandanan shipwreck site with one of NMP underwater archaeologist. Photo by Gilbert Fournier, 1995. |

The glass beads from the Pandanan shipwreck consist of only two colors – opaque red and black. In 2006, Jun Cayron from the University of the Philippines-Archaeological Studies Program conducted a research entitled “Stringing the Past: An Archaeological Understanding of Early Southeast Asian Glass Bead Trade”, where he sourced the Indo-Pacific beads from Pandanan shipwreck to Sungai Mas site in Malaysia. This provided significant data on the bead trade pattern and distribution in Southeast Asia. Local products such as cotton, yellow wax, pearls, tortoise shells, and medicinal betel nuts were most likely used to trade for these beads.

_______________

Text and poster by the NMP Maritime and Underwater Cultural Heritage Division

© National Museum of the Philippines (2021)

Stone Ballasts

Ballasts are additional weights that ships must carry to compensate for the increased buoyancy and provide trim and balance. They influence vessel stability during unpredictable weather conditions and increase survivability at sea. Research shows that 10% of the ship’s tonnage is equivalent to the required weight of ballasting materials needed.

|

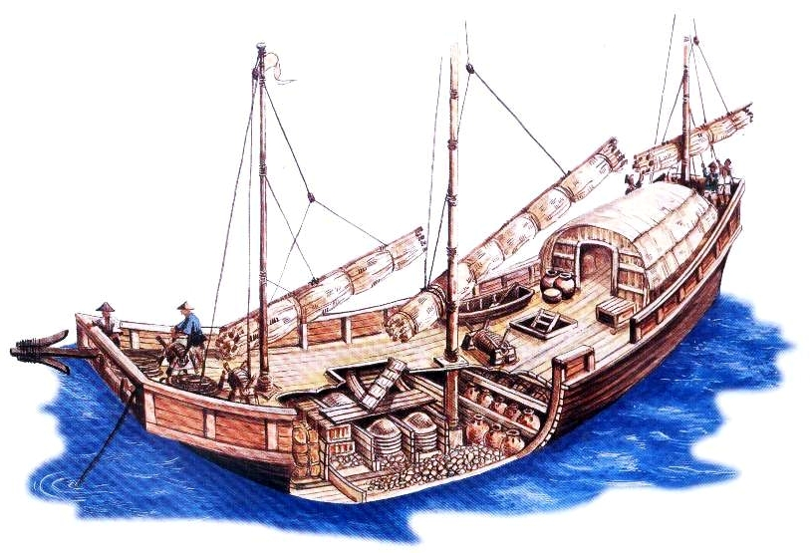

| A cross section of a merchant ship and the relative location of stone ballasts. |

The stone ballast has probably been used since the beginning of seafaring. Before the late 19th Century CE, ships used solid ballast materials such as rocks and sand. Metals, dirt, corals, and water were also used as ballasts and can be found mixed with stone ballasts or used on their own. More often, rounded or stream-worn stones were preferred as ballasting materials to avoid abrading the ship’s hull. Stones can be added or removed as warranted by sea conditions. In ports, stone ballasts were usually dumped in the water in exchange for trade materials. On the other hand, ships are loaded with ballasting materials when their cargo holds are empty. Over the years, archaeological excavations exposed these stones in ancient harbors and shipwreck sites. Studies have also revealed that ballast stones were later used as building and paving materials and even as grave markers.

|

| A diver holding an artifact on siting on top of stone ballasts mound at the San Diego shipwreck site. |

Stone ballasts are often regarded as “with no commercial value” and not looted, thereby providing ample materials for archaeological investigations. The National Museum of the Philippines (NMP) maritime archaeologists have recorded stone ballasts in more than 20 shipwreck sites during archaeological explorations from 1981 to 2019. Currently, the NMP has collected 20 stone ballasts from different shipwreck sites in the country. Six rounded stone ballasts were recovered from the Pandanan shipwreck in southern Palawan. The stones were of volcanic and sedimentary rock materials that may suggest different sources and ports of origin. Thirteen basalt rocks (previously reported as granite stones) of various shapes and sizes were also recovered from Thitu Reef, in the Kalayaan Group of Islands in the West Philippine Sea during exploration and excavation in 1996. The stones had different size and shapes and its weight ranged from 3,225 grams to 9,850 grams. These were believed to have been traded as building materials for Hindu temples based on other associated materials such as stone pillars with architectural designs and grave markers. A volcanic rock (possibly andesite) was also recovered recently from San Jose galleon shipwreck in Lubang Island, Occidental Mindoro during an archaeological survey and exploration in 2019 and 2020.

|

| Stone ballasts mound in in a shipreck site in Catanauan, Quezon Province. |

While it is undeniable that porcelain and stoneware ceramics, potteries, jewelry, as well as gold and silver wares have commercial value and of great interest to the general public, stone ballasts are also useful archaeological data in uncovering shared maritime stories about the past. They can also provide direct evidences of international mobility and exchange as can be seen in shipwrecks, ports, and harbors.

Vietnamese Blue and White Ceramics

We also highlights the Vietnamese blue and white ceramics recovered from the Pandanan shipwreck in Pandanan Island, Balabac Municipality, southern Palawan Province.

|

| Photomosaic of the Pandanan vessel. |

Pandanan shipwreck contained predominantly stoneware Vietnamese ceramics along with a limited number of porcelain and stoneware ceramics from China and Thailand, as well as metal, glass, wood, and organic materials.

|

| Finding a Vietnamese blue and white bowl during the Pandanan excavation. |

A hundred pieces of Vietnamese blue and white ceramics in the form of bottles, jars, jarlets, dishes, and bowls were retrieved. These were produced by the Chu Dau kilns in Hai Hung Province, northern Vietnam. The Chu Dau kilns were the only producers of underglaze blue wares besides China during the 14th to 16th centuries. The stylistic motifs such as plants, landscape, animals, and scrolls of the Chu Dau pieces bear great similarity with the Chinese styles. The Vietnamese potters were greatly influenced by Chinese potters over long periods of their history, especially after the Chinese occupation in the early 15th century CE.

|

| Stoneware jars and bowls from Vietnam where discovered at the Pandanan wrecksite. |

Despite this, Vietnamese potters incorporated their own distinct styles that make it quite different from the Chinese pieces. A peculiar technique for the Chu Dau ceramics is the iron wash painted on the base of the vessels, popularly known as ‘chocolate bottom’. This treatment varies in color from reddish- to dark-brown and gives a distinct and diagnostic look to the pieces.

Bronze cannon

Two years later, the site was archaeologically excavated and yielded remains of a wooden ship that contained over 4,000 artifacts from different countries. A Chinese coin dated to the reign of Chinese emperor Yongle (1402–1424) of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644) provided the basis of the relative dating of the site but the overall analysis of the archaeological assemblage points to the middle to late 15th century as the sinking date. Among the significant finds are the two small bronze cannons of unknown origin.

|

| The bronze cannon in situ, found along the keel of the wrecksite. Photo by Gilbert Fournier. |

The cannon photographed in this post measures about 27 cm long and was highly eroded that many features are difficult to recognize. The absence of cylindrical projection for mounting or pivoting point called trunnions suggests the manner in which the cannon was handled. The socketed cascabel feature indicate that the cannon may be stock mounted.

|

| The Pandanan shipwreck site plan. Illustration by Ed Bersamira, layout enhanced by E. Reyes (NMP EEMPSD). |

The oversized hemispherical muzzle is indicative of a blunder-buss function, designed to obstruct a personnel not behind armor. When the cannon is fired, the muzzle widening serves to contain its flare. Metallurgical analyses have yet to be done on the cannon to provide more details on its origin, type, and function.

In the Philippines, a common term for a small culverin or brass cannon normally with a forked swivel mount is “lantaka”. This is known among Maranaos, Maguindanaos, Tausugs, Cebuanos, Warays, and Tagalogs. The word lantaka and the rich metal-working expressions demonstrate an early metallurgical tradition in the country prior to colonization.

_________

Text and Poster by Nero M. Austero/MUCHD

Photo © Franck Goddio and World Wide First Inc.

© Poster Background Photo by Mike Barrow

©National Museum of the Philippines (2020)

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?