The Cebuano People of the Philippines [Mga Bisaya] - History, Culture and Traditions [Cebu Province - Kultura ng Kabisayaan]

“Cebuano” comes from the root word Cebu, the Spanish version of the original name Sugbo, which comes from the verb sugbo, meaning “to walk in the water.” In the old days, the shores of the Cebu port were shallow, so travelers coming from the sea had to wade in the water to get to dry land. The term is suffixed with hanon to refer to the language, culture, and inhabitants of Cebu; thus, Sugbuhanon or Sugbuanon. Sugbuhanon was later modified by the Spaniards to Cebuano and by the early Americans to Cebuan. Today “Cebuano” may also refer to the speaker of the language no matter where he comes from.

The Cebuano are also called Bisaya, although this is a generic term applying not only to the Cebuano but to other ethnic language groups in the Visayas. The etymology of “Bisaya” is uncertain although it is probably linked either to the word meaning “slaves,” for the region was either a target or staging area for slave-raiding forays in precolonial and early colonial times; or it could mean “beautiful,” which was what a Bornean sultan declared upon seeing the islands, according to a popular tale.

Cebuano is the first language of about a quarter of the Philippine population or around 15.8 million Filipinos today. It is dominant in Cebu, Bohol, Negros Oriental, Siquijor, Camiguin, sections of Leyte and Masbate, and is spoken by the majority of Visayan settlers in Mindanao, particularly in the Davao provinces, General Santos, Bukidnon, Iligan, Cagayan de Oro, Surigao, Butuan, and Agusan. It belongs to the Austronesian family of languages, which, in the Philippines, has split up into many language groups or subgroups.

The Cebuano language chiefly defines the Philippine ethnic group also referred to as Cebuano. The core area of this group is the province of Cebu, an elongated mountainous island with some 150 scattered islets. Encompassing a total land area of 5,000 square kilometers, Cebu province is bounded in the north by the Visayan Sea, in the east and northeast by Bohol and Leyte, and in the west and southwest by Negros across Tafton Strait. Cebu is located in the geographical center of the archipelago. This region—with four provinces, 16 cities, 116 municipalities, and almost 3,003 barangays or villages—has a combined population of 6.8 million. Cebu City is the second largest metropolis in the nation.

The cultural reach of the Cebuano extends beyond Central Visayas. The dense population and a lack of arable land have made Cebu and Central Visayas an important source area for population emigration. It is for this reason that the Cebuano constitute a significant part of the populations in other parts of the Visayas and Mindanao. Moreover, the role of Metro Cebu, the country’s second largest urban concentration, as southern center of education, media, and transportation, enables Cebu to exercise cultural influence beyond provincial or regional boundaries.

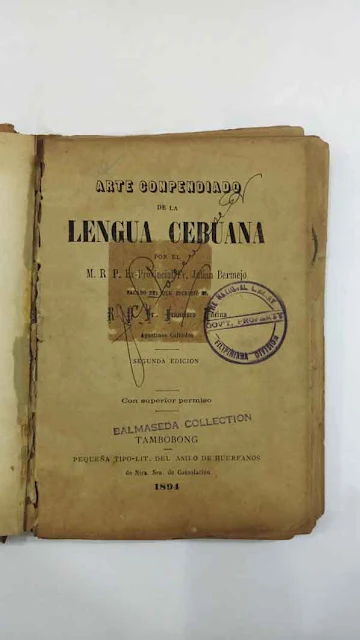

The Visayan that is spoken in Cebu, Bohol, and Davao belong to the same language, with some phonetic and syntactical peculiarities. During the Spanish period, the Catholic Church translated the Bible into a variant of Cebuano spoken in southeastern Cebu. Known as the Sialo vernacular, this translation became the standard for written Cebuano. Sialo refers to the precolonial territory that included the towns of Carcar and Santander in southern Cebu.

Over the years, Cebuano speakers outside of Cebu have asserted the distinctions of their vernaculars. This was evident in the 2000 Census, which created the separate language categories Bisaya, Boholano, and Cebuano. According to the 2000 Census, 8% of the population identified the language they spoke as Bisaya or Binisaya. In everyday speech, many Cebuano speakers use the term Bisaya to refer to the language, even though there are other languages in the Visayas.

In the Cebuano variant spoken in Cebu City, the “l” is dropped and replaced with “w” in certain words. In Bohol towns facing Southern Leyte, the “y” in certain words is spoken as a hard “j,” while there are also words exclusive to Bohol. Cebuano-Davao has two varieties: The first one is a combination of the vernaculars spoken in southeastern Cebu and Cebu City; the second is a hybrid of Visayan and Luzon languages, containing some syntactical features of Tagalog and lexical borrowings from Hiligaynon and other languages.

For written Cebuano, the Sialo vernacular continues to be the standard. The house style of Manila Bulletin’s Bisaya Magasin, which also adopts the Sialo variety, is influential among literary writers.

As for spoken Cebuano, there is yet to be a standard. The varieties of Cebuano spoken in Visayan towns outside Cebu and parts of Mindanao that are considered economic centers have gained prominence due to the influence of writers groups, mass media, and academic institutions.

History of the Cebuano People

As early as the 13th century, Chinese traders noted the prosperity of the Cebuano, with whom they traded various porcelain plates and jars from the late Tang to the Ming, which were used by the natives for everyday life or buried in the graves. The traders also remarked how the Visayan, when not engaged in trade, raided Fukien’s coastal villages, using Formosa as their base. Reportedly, the Visayan rode on foldable bamboo rafts and, when attacking, were armed with lances to which were attached very long ropes so that they could be retrieved to preserve the precious iron tips.

|

| Depiction of Visayan man and woman, circa 1590 (Boxer Codex, The Lilly Library Digital Collections) |

In the early 16th century, the natives of Cebu under Rajah Humabon engaged in an active barter trade of woven cloth, embroidery, cast bronze utensils, and ornaments. The settlement also had small foundries producing mortars, pestles, wine bowls, gongs, inlaid boxes for betel, and rice measures. Humabon himself was finely clad in a loincloth, silk turban, and pearl and gold jewelry, and was supposed to have demanded tribute from East Indian, Siamese, and Chinese traders. At that time, densely populated villages lined the eastern coast of the island, while the highland villages hugged the streams and lakes. The coasts were linked to the hinterlands either by rivers or trading trails. Communities were composed of bamboo and palm leaf-thatched houses raised from the ground by four posts and made accessible by a ladder, with the area underneath reserved for domestic animals. Humabon’s large house resembled the common dwellings, towering like a big haystack over smaller ones.

|

| Mural on the ceiling of the kiosk of Magellan’s Cross (Cebu, Pride of Place by E. Billy Mondoñedo. Arts Council of Cebu Foundation, Inc., 2007.) |

On his way to the Moluccas, Ferdinand Magellan landed in Cebu on 7 April 1521 and planted the seeds of Spanish colonization. Rajah Humabon and his wife, baptized Juana, were Christianized following a blood compact between conquistador and native king. However, Lapulapu, chieftain of Mactan, refused to accept Spanish sovereignty. Outnumbering the foreigners by 1,000, his men killed Magellan, eight Spanish soldiers, and four of Humabon’s warriors. Duarte Barbosa and Juan Serrano, who took command after Magellan’s death, were also killed along with their soldiers during a goodwill banquet hosted by Humabon. The remnants of Magellan’s expedition under Sebastian del Cano sailed homeward defeated, but proving for the first time that the earth is round.

|

| Lapulapu statue, Cebu (wikimediacommons/Alpapito) |

The second Spanish expedition to the Philippines, headed by Miguel Lopez de Legaspi and Andres de Urdaneta, reached Cebu on 27 April 1565. As in the earlier experience, the native reception of Legaspi was initially amiable, with a blood compact with Sikatuna, chieftain of Bohol, even taking place. Later, Tupas, son and successor of Humabon, battled with the Spaniards, who easily killed some 2,000 warriors equipped merely with wood corselets and rope armor, lances, shields, small cutlasses, arrows, and decorative headgear. Their native boats, “built for speed and maneuverability, not for artillery duels,” were no match for Spain’s three powerful warships.

Legaspi, accompanied by four Augustinians, built the fort of San Miguel on 8 May 1565. This was the first permanent Spanish settlement in the archipelago. Cebu was the capital of the Spanish colony for six years before its transfer to Panay and then to Manila. Many Cebu warriors were recruited by Legaspi, Goiti, and Salcedo to conquer the rest of the country.

Tupas signed a treaty tantamount to submission on 3 July 1565, for which he was given a 13-meter brown damask. On 21 May 1568, shortly before his death, Tupas was baptized by Father Diego de Herrera—an event which propagandized Spanish rule. On 1 January 1571, the settlement was renamed Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus (City of the Most Holy Name of Jesus) in honor of the image of the Child Jesus that had been found in a house left unscathed in the wake of the Spanish invasion of 1565—the site of the present Augustinian Church. It was believed to be a relic of Magellan’s expedition, the same one given to “Queen Juana” upon her baptism.

In the 1600s, Cebu had been one of the more populous Spanish settlements in the country, usually with about 50 to 100 Spanish settlers residing there, not including the religious. However, this dwindled sharply after 1604, when Cebu’s participation in the galleon trade was suspended. Cebu had annually outfitted and dispatched a galleon to New Spain. Profits were minimal because of restrictions imposed on the items that could be loaded, at the instigation of Spanish officials who wished to maintain the Manila-Acapulco trade, which was the more profitable venture. Moreover, one galleon from Cebu sank in 1597.

The nonparticipation of Cebu in the galleon trade greatly diminished its importance, and by the late 1730s, there were only one or two Spaniards who lived in Cebu City who were not government officials, soldiers, or priests. Few Spaniards owned land in the countryside, a situation further buttressed by a decree that forbade the Spaniards from living among the Filipinos until 1768.

Italian traveler Gemelli Careri in the late 17th century and French scientist Le Gentil in the 18th both noted Cebu’s commercial poverty. The island had become a mere outpost. Interisland trade was further restricted by two factors: the threat of so-called Moro raids from Mindanao and Moro pirates on the seas, which continued way into the late 1790s; and the attempts of the alcaldes-mayores (provincial governors) to monopolize domestic trade for their own personal economic advantage. These alcalde-mayores were allowed to purchase the special license to trade to make up for the fact that the Spanish central administration perennially lacked funds to give as salaries to its local officials and bureaucrats.

As Spanish officials recovered from the short-lived British occupation of Manila from 1760 to 1762, they began to institute reforms that eventually made the atmosphere more conducive to trade. Cebu’s trade slowly became rejuvenated.

The opening of the Philippines to world trade in 1834—and subsequently of Cebu in 1860—stimulated economic activity in Cebu. Sugar and hemp became important cash crops for Cebu’s economy. Sugar had already been previously grown in Cebu even before Magellan arrived. Identified as one of the four varieties of sugar to be found in the Philippines during the Spanish period was a strain called Cebu purple. The vastly increasing demand for cash crops meant, as in most other areas of the Philippines, a big change in land ownership patterns. Land was increasingly concentrated in the ownership of a few hands, usually through the method of pacto de retroventa, whereby land was mortgaged by its original owners to new cash-rich landowners on the condition that it could be bought back at the same price on a certain date. This system, which favored the creditors, created a new class of wealthy landlords and a mass of landless agricultural wage laborers, both of which grew agitated against the Spanish administration and the power of the religious. This pattern was familiar to the rest of the country.

The Cebu revolutionary uprising was led by Leon Kilat, Florencio Gonzales, Luis Flores, Candido Padilla, and Andres Abellana. On 3 April 1898, they rose against the Spanish authorities in Cebu. Furious fighting took place on Valeriano Weyler Street, now Tres de Abril, and other parts of the city. The revolutionaries drove the Spaniards across the Pahina River and finally to Fort San Pedro. They besieged the fort for three days but withdrew when the Spaniards sent reinforcements from Iloilo and bombarded the city.

Spanish rule in Cebu ended on 24 December 1898, in the wake of the Treaty of Paris signed on 10 December. The Spaniards, under Cebu politico-military governor Adolfo Montero, withdrew from the city and turned over the government to a caretaker committee of Cebuano citizens. The Philippine Government was formally established in Cebu City on 29 December 1898, and revolutionary head Luis Flores became the first Filipino provincial governor of Cebu.

The American occupation ended the republican interregnum. After the occupation of Iloilo on 11 February 1899, the Americans started closing in on the Visayas. Days earlier, a group that included provincial officials of the newly established civil government gathered at the Casa Real to plan the war. Luis Flores, Miguel Logarta, Juan Climaco, Arcadio Maxilom, and Pablo Meija were among those in attendance. However, class tensions among these personalities led to factions. During a meeting on board the American vessel Petrel, the Cebuano civil officials debated whether or not to surrender or wage war. As a result, two factions emerged: the moderates who favored surrender, led by Julio Llorente and Pablo Mejia, and the younger officials who wanted to resist, led by Arcadio Maxilom and Juan Climaco. The moderates won the argument. Under threat of US naval bombardment, Cebu City was surrendered to the Americans on 22 February 1899. However, a province-wide war ensued under the leadership of Climaco and Maxilom.

The Cebuano army retreated to the highlands and broke into smaller guerilla troops, a strategy which Maxilom had adapted from that of Emilio Aguinaldo. These bands moved around the province sabotaging American communication lines and recruiting more insurgents and civilian allies. Meanwhile, the Americans, whose units were being attacked all over Cebu, began ransacking towns and torching houses in an effort to terrorize civilians into submission.

Class tensions and the lack of cohesion and a stable leadership hounded the resistance. The defection of the ilustrado (the educated) members of the civil government splintered a united front against the Americans. At the onset of war, the insistence on fighting from fixed positions instead of applying guerrilla tactics cost the resistance movement their artillery and soldiers. Meanwhile, collaborators and American sympathizers were growing in number. The Catholic leadership in Cebu looked after its own interests, and several businessmen wanted stability and order. The war killed around 1,000 Cebuano. The Americans had only 100 casualties.

Cebuano resistance to US rule was strong but had to submit to superior American arms with the surrender of the Cebuano generals in October 1901. Along with 78 men, Maxilom surrendered to Lieutenant John L. Bond of the 19th US Infantry in Tuburan on 27 October. Maxilom became instrumental in coaxing other leaders of the resistance in the Visayas to surrender. However, insurgent groups and bandits of mixed persuasions, all of whom were generally called the pulahanes, kept up the fight against the Americans until 1906.

The Americans introduced public education, promoted industry, and reorganized local government. In 1901, Julio Llorente was appointed civil governor of Cebu. All previous laws and ordinances observed were permitted to continue. Eventually, the municipal board positions were no longer filled by appointment but through popular elections. In 1902, an election was held in Cebu City for the governor of the province. Juan Climaco won with 249 votes against Llorente, who received 122 votes.

With the consolidation of American rule in Cebu and its nearby provinces, the local elites and intellectuals, including those who fought during the two phases of the Philippine Revolution, ventured into the civil administration by standing for election in the local government. One of these individuals was a young lawyer named Sergio Osmeña, Sr., who was known for writing nationalist articles for the Cebuano daily El Nuevo Dia. At age 25, Osmeña was appointed as the acting provincial governor of Cebu by Governor-General Luke Wright (Valencia 1977). The young Osmeña then climbed the political ladder starting as the provincial fiscal of Cebu and Negros Oriental in 1904 and later serving as governor of Cebu Province in 1906. Soon he was thrust into mainstream politics, forming the Partido Nacionalista with Manuel L. Quezon for the elections for the Philippine Assembly in 1907 and later becoming the Speaker of the Philippine Assembly (later the House of Representatives) until 1922, when he was elected senator (Cullinane 1989). With the inauguration of the Commonwealth in 1935, Quezon and Osmeña were elected President and Vice-President respectively and re-elected in 1941 (Mojares 1994). Vice-President Osmeña later assumed the presidency upon the demise of Manuel Quezon in August 1944 and soon after returned to the Philippines with General Douglas MacArthur. With the return of civilian administration in 1945, Osmeña restored the various functions of the branches of government and started the immediate economic rehabilitation of the country. After his defeat at the presidential elections of 1946, Osmeña retired from politics (Santos 1999). But his descendants continued to dominate Cebuano politics for decades after.

By the 1930s, under the American Homestead Settlement Act, Visayan settlers were arriving by the thousands in Mindanao, mostly from Cebu and Iloilo. Most of the Cebuano settled along the Davao Gulf, which was then known for abaca and coconut plantations. The Americans encouraged this wave of migration from Luzon and the Visayas to defuse peasant uprisings in these areas and, in Mindanao, to counteract the resistance of Muslim and indigenous communities and the growing population of Japanese settlers. Most of the settlers who arrived in Mindanao were peasants who took the opportunity to be given land and employment; but there were also educators, entrepreneurs, and other professionals.

Today, the Cebuano-speaking population in Mindanao continues to influence the cultural and political landscape of the region. The largest Cebuano communities on the island are found in towns along the Davao Gulf, making Cebuano-Visayan one of the most widely used languages in Mindanao. Both Davao and Cagayan de Oro have a circulation of Cebuano-language radio, TV programs, and newspapers. Entrepreneurs in Cebu extend their businesses into urban areas in Cagayan de Oro, Davao, and General Santos. A number of political leaders in Mindanao are of Cebuano descent.

Cebu became a chartered city on 24 February 1937. Vicente Rama authored and secured the approval by Congress of the Cebu City Charter. The Charter changed the title of “presidente” to mayor. Alfredo V. Jacinto served as mayor by presidential appointment.

On 10 April 1942, the Japanese landed and seized Cebu. Over half the city was bombed. Cebu’s USAFFE (United States Armed Forces in the Far East), Constabulary forces, and some ROTC units and trainees staged a brief and unsuccessful offensive. A few surrendered to the Japanese, on orders of General Wainwright, supreme commander of the United States Forces in the Philippines. Many fled to the mountains and later reorganized into guerrilla bands, which harassed the Japanese throughout their occupation and facilitated the entry of the American forces into the province. As elsewhere in the country during wartime, suspected collaborators were tortured and killed.

Notorious for such summary executions of suspected collaborators in Cebu was the group led by Harry Fenton, who held sway in northern Cebu, while James Cushing controlled those operating in central and southern Cebu. For his many abuses against comrades and civilians, Fenton was executed by the guerrillas on 1 September 1943. James Cushing assumed command of Cebu’s anti-Japanese resistance movement, which was one of the most effective in the country. By the time MacArthur returned to the Philippines in October 1944, Cushing had about 25,000 men, half of whom were armed and trained.

Juan Zamora administered the city of Cebu during the war. Upon the return of the Americans in March 1945, Leandro A. Tojong was appointed military mayor of Cebu. Following the post-“liberation” general elections on 23 April 1946, Manuel Roxas was elected Philippine president. In 1946, he appointed Vicente S. del Rosario as mayor of Cebu, the first to serve the city at the dawn of the Third Republic. The Charter of the City of Cebu was amended in 1955 to make the post of mayor elective. Sergio Osmeña Jr. was overwhelmingly elected mayor.

In 1969, Osmeña ran for president under the Liberal Party against Ferdinand Marcos, who was running for a second term under the Nacionalista Party. Osmeña openly criticized Marcos’s corrupt administration, thereby establishing him as Marcos’s fierce political rival before martial law was declared. Marcos won the election, but Osmeña and the Liberal slate accused their opponents of election fraud. In 1971, Osmeña was wounded when two grenades exploded at a Liberal Party campaign at the Plaza Miranda in Manila. When Marcos declared martial law in 1972, Osmeña escaped to the United States. The Philippine government identified him as a key figure in an assassination plot against Marcos. Osmeña remained in the United States until his death in 1984 from respiratory failure.

Several members of the Osmeña clan became political prisoners, while others were exiled in the United States. Sergio R. Osmeña III, son of Sergio Osmeña Jr., was arrested and imprisoned in Fort Bonifacio until he escaped by digging a tunnel in 1977 with Eugenio Lopez Jr. He joined relatives in the United States, during which he served as the director of the Movement for a Free Philippines and the Justice for Aquino, Justice for All. Osmeña III returned to the Philippines after the EDSA Revolt and won a seat at the Senate in 1995.

Emilio Mario Osmeña was imprisoned for nine months in Fort Bonifacio and for four years was placed under house arrest. After the assassination of Benigno Aquino, Emilio Osmeña ran for governor of Cebu and won. John Henry Osmeña, who had been in Plaza Miranda in 1971 as a senatorial candidate, flew to the United States after martial law was declared, even though he had been elected senator the previous year. After Aquino’s assassination, John Osmeña returned to the Philippines and helped in the campaign against Marcos.

Cebu’s distance from Manila made it a safe location for opposition leaders to plan a revolt. Corazon Aquino stayed in Cebu for four days during the EDSA Revolt. Student protest leaders such as Jorge L. Cabardo, who helped Sergio Osmeña III escape from Fort Bonifacio, led student demonstrations against Marcos’s regime. Cabardo had come to Cebu to study at the Cebu Institute of Technology, having already been a student activist at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. Father Rudy Romano led demonstrations against Marcos, most of which ended violently, even after the lifting of martial law. The protests led by Father Romano were seen as more dangerous to the regime because they were not motivated by political factions, but by the grievances of farmers and ordinary citizens. On 11 July 1985, Father Romano disappeared after state forces arrested him. In 2012, a marker was placed in Cebu City’s Plaza Independencia to honor all Cebuano who lost their lives fighting against Ferdinand Marcos’s regime.

Decades after the EDSA Revolt, Cebu’s political field continues to be dominated by the Osmeñas and the Garcias, clans from which two Philippine presidents have emerged. The most prominent descendants from both sides are Gwendolyn Garcia and Tomas Osmeña, the son of Sergio Osmeña Jr. Garcia served as Cebu governor in 2004 to 2012; Osmeña served as Cebu City mayor in 1988 to 1995, and again in 2001 to 2010. Each was critical of the other’s administration. One instance was their public dispute over a failed land swap deal between the province and the city.

During her term, Garcia, the first female governor of Cebu, weathered a graft case over a questionable land purchase and was reelected in 2010. Two years into her second term, she was given a six-month suspension by President Benigno Aquino III for “grave abuse of authority.” In 2013, after her suspension, Garcia went on to win a seat in Congress. In the same elections, Tomas Osmeña lost the mayoralty seat to the incumbent Michael R. Rama.

Cebu Economy

Long before even the colonial era, Cebu has been a distribution center of the Central Visayas; hence, its economy continues to rely on nonagricultural sectors. This emphasis, brought about by the lack of wide expanses of arable land, has propelled Cebu to sustain economic prosperity, especially in the last two centuries.

|

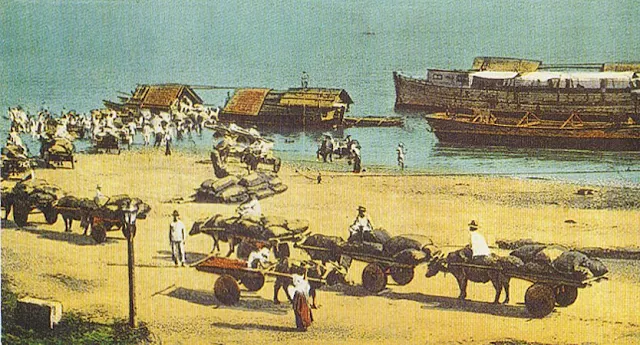

| Loading of copra in the port of Cebu, circa 1910 (Photo courtesy of Cebuano Studies Center) |

The many industries in the cities of Cebu, Mandaue, and Lapulapu take advantage of the fine harbor protected on the east and south by Mactan Island and on the north and west by the Cebu mainland. The port of Cebu, now an international port, is headquarters for 22 shipping firms, among them some of the leading interisland shipping companies in the country such as Aboitiz Shipping Corp, William Lines, Sulpicio Lines, George & Peter Lines, and Sweet Lines. More ships of domestic tonnage call at Cebu Port than in Manila.

The other major point of entry to the province is Mactan International Airport on Mactan Island, which is connected to Cebu City by the 864-meter span Mandaue-Mactan Bridge. The airport, the hub of air transportation in the south, links Cebu not only to the rest of the country but to such points as Hong Kong, Singapore, Guam, and Tokyo.

Cebu’s position as a transport and communications center underlies its principal economic activities. Around 90% of business establishments in Cebu City are in these sectors, thus making it primarily a center of trade and commerce. However, Cebu is also a manufacturing and industrial center. It is the site of the Mactan Export Processing Zone established in 1980. Metro Cebu has LUDO & LUYM Corporation, known for the processing and export of coconut oil and coconut, corn, and cassava-based products, and for such establishments as Aboitiz Jebsen Co., AboitizLand, Ayala Land Inc., Cebu Holdings Inc., International Pharmaceuticals, Norkis Industries, and the Cebu plants of corporations like San Miguel Brewery. Other enterprises engage in the manufacture of liquor and beverages, paper products, ceramics, chemicals, metal products, and rubber and plastic products. It is also a center in the production of export crafts and giftware made of rattan, shell, wood, bamboo, stone, and others.

Danao, a city of some distance away from the Cebu-Mactan hub, has a cement factory and a paper bag factory. Toledo City is the site of Atlas Mining, the leading producer of copper in the country. In addition to copper, Cebu boasts of rich coal and cement deposits with the possibility of some untapped oil resources. In more modest quantities are to be found gold, silver, molybdenum, limestone, dolomite, feldspar, and rock phosphate. Cebu has drawn many large commercial firms and banks from Manila and foreign countries, and houses a branch of the Central Bank and banking establishments, such as Rural Banking Association of the Philippines, Bank of the Philippine Islands, Banco de Oro, Asia United Bank, Metrobank, and Philippines Veterans Bank among others. In 2010, the province had 445 banks that recorded deposits of around 218,554 million pesos, which was the largest in the country.

Further indication of Cebu’s progress is its growth of per capita gross domestic product in 2011, which was 372.2 billion pesos or 3.8% of the country’s GDP. Starch, soy sauce, garment, shoe, slipper, paper, tile, brick, and glass factories and some foundry shops, tanneries, fertilizer, ice, bottling, truck and car assembly plants generate employment. Unlike other provinces, Cebu has no serious labor problem.

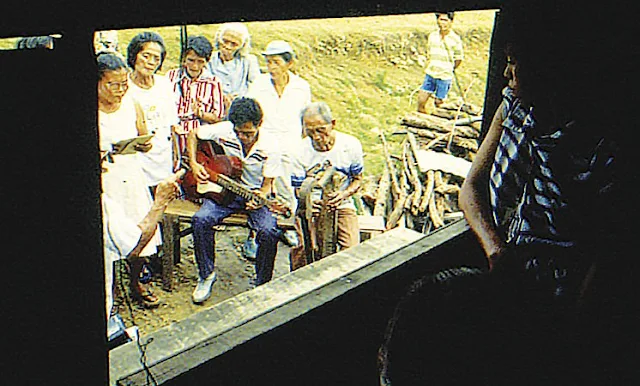

Not all of Cebu’s industries are concentrated on manufacturing. Mandaue City is the home of traditional Cebuano crafts: mats, brooms, rattan furniture, shell craft, and ceramics for both export and domestic use. Argao and the southern parts are weaving centers. Mactan is recognized as the country’s source of handmade guitars, ukuleles, bandurrias, and violins, which are sold locally and exported to Japan, Australia, and Germany.

|

| Fisherman and traders at a fish landing in Cebu, circa 1900 (Cebu, More Than An Island by Resil B. Mojares and Susan F. Quimpo. Ayala Foundation, Inc., 1997) |

Cebu’s extensive fishing industry commercially processes sardine, herring, salmon, mackerel, and anchovy in the northwestern parts. Fish is a mainstay of the Cebuano diet, together with corn, although locally produced corn cannot adequately feed the provincial population. Cebu also grows sugar, tobacco, and coconut fiber. Other export products are Toledo’s bananas, Carcar’s pomelos and grapes, and mangoes from Guadalupe in Cebu City. Native delicacies include dried mangoes, turrones, and Rosquillos biscuits.

The educational capital of the south, Cebu attracts students from Mindanao and the Visayas who attend its private and state-owned institutions, notably the University of San Carlos, University of San Jose-Recoletos, University of the Visayas, and University of the Philippines Cebu. Cebu City has some 68 public schools and 65 private schools, nine of which have university status.

Video: Miss Universe Philippines 2021 Tourism Videos | Cebu City

Tourism is another income earner. Cebu City, the oldest Catholic city in the Orient, is both cosmopolitan and historic; its quaint horse-drawn carriages called tartanillas persist amid luxury hotels and department stores. Among Cebu’s Spanish colonial landmarks are Magellan’s Cross, the Santo Niño Basilica, the Fort San Pedro, the Metropolitan Cathedral, the Legaspi Monument on Plaza Independencia, and the Moro watchtowers at Boljoon and other areas. Tourists can also seek modern amusements like golf courses and country clubs, restaurants and discotheques, and numerous beach resorts in Mactan, Argao, and Danao.

In 2013, an earthquake with a magnitude of 7.2 hit the Central Visayas, damaging churches in Cebu, some of which were built in the 16th century. The quake destroyed the belfry of the Basilica Minore del Santo Niño, and it created cracks on the belfry and facade of the 19th-century Cebu Metropolitan Cathedral. Private sectors and government agencies have since vowed to restore these churches. The earthquake also damaged business establishments, including the Gaisano Country Mall in Banilad and the Cebu Doctors’ University.

|

| Cebu workers processing mangoes (Michiko Nina Gandionco) |

With Cebu as its center, the Central Visayas is one of the most economically vibrant regions in the country. Exports from Central Visayas totaled 2.3 billion US dollars in 2011. The leading exports of the region include abaca pulp, copper concentrate, dried mangoes, carrageenan (seaweed extract), seaweed flour, activated carbon, drilling machine accessories, rattan and wood furniture, coconut shells, and coco fatty acid distillate.

Digital technology and real estate investments in the 2000s have caused further economic growth. The most active industries in Cebu are business process outsourcing (BPO), real estate, tourism, and the service industry. Information technology centers, particularly in Lahug, employ around 95,000 workers. The Board of Investments (BOI) confirmed in 2011 that 14 firms expressed an interest in initiating projects amounting to 12.1 billion pesos. In 2012, the construction sector built 7,000 condominium units. In the same year, the manufacturing sectors earned 3.6 billion dollars in exports. The industry and service sectors comprise 92.2% of the economy of Central Visayas.

Cebu's Colonial Political System

Archaeological evidence indicates that present-day Cebu City was already a settlement as early as the l0th century. From the mid-14th century to the time of Spanish contact, Cebu expanded as a trading and administrative center linked to other settlements on the island of Cebu and other places in Visayas, Mindanao, and beyond. Interregional and long-distance trade led, among others, to increasing complexity in the social and political structure of Cebu, such that by the 16th century, the port settlement of Cebu was ruled by a rajah such as Humabon and Tupas, who exercised influence over a larger number of followers, retainers, and lesser datu. While Cebu was developing into what has been called a “super-barangay,” the general situation in Cebu and the Central Visayas was one characterized primarily by a large number of relatively autonomous barangay or balangay, loosely linked together by relations of trade and exchange. Spanish colonization beginning in the 16th century revised the political landscape as the Spaniards embarked on the creation of a unitary colonial state out of the territories they annexed. This, of course, was a long drawn-out process.

|

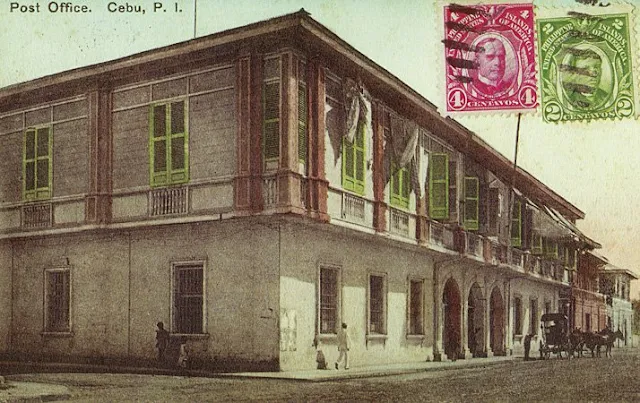

| Old provincial capitol, circa 1910, shown in an American-period postcard (Lucy Urgello Miller Collection, photo courtesy of University of San Carlos Press) |

Cebu was the site of the first Spanish settlement in the archipelago and the capital of the colony-in-the-making until the transfer of the Spanish seat of government to Manila in 1571. On 8 May 1565, Legazpi took “formal possession” of Cebu and called the Spanish settlement “Villa de San Miguel.” On 6 August 1569, King Philip II issued a decree granting the title “Governor and Captain-General” of Cebu to Legazpi. On 1 January 1571, Legazpi reestablished the settlement of Cebu, renaming it Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus, appointing “city officials,” and distributing encomiendas in Cebu and neighboring islands to Spaniards.

The creation of a colonial political system was slowed down by a host of factors: lack of Spanish personnel and resources, geographic and cultural particularism, and native resistance to Spanish rule. It was only in the 19th century that the colonial state took a more full-bodied shape. In large part, this was due to economic changes ushered in by the “opening up” of the countryside to world trade and population growth. In Cebu, 44 towns were established in the 19th century as against only 13 towns founded in the centuries before 1800. This was the pattern as well in the rest of Central Visayas.

Cebu was one of the earliest provinces to be organized in the archipelago. It was already an alcaldia or civil province in the 16th century. Throughout much of the 16th and 17th centuries, the province of Cebu encompassed such areas as Bohol, Leyte, Samar, Negros, Masbate, and Mindanao. The island of Negros became a corregimiento, an unpacified province under a military governor in 1734 and an alcaldia in 1795. On 25 October 1889, a royal decree established Negros Oriental as a separate province, with Dumaguete as capital. Earlier, Bohol was separated from Cebu and became a province on 22 July 1854. Siquijor, at various times a part of Cebu, Bohol, and Negros Oriental, became an independent province on 1 January 1972.

The Americans reorganized provinces by abolishing towns or creating new ones. However, the basic political organization of the Spanish period remained. The important innovation was the introduction of popular suffrage and the “Filipinization” of government, such that Filipinos occupied not only the municipal positions they had under Spanish rule but provincial and national positions as well.

Today, Cebu is administratively divided into 6 congressional districts, 9 cities, 44 municipalities, and 1,203 barangays. Negros Oriental has 3 congressional districts, 6 cities, 20 municipalities, and 557 barangays. Bohol has three congressional districts, one city, 47 municipalities, and 1,109 barangays. Siquijor has one congressional district, 6 municipalities, and 134 barangays.

These four provinces constitute Region VII, with Cebu City as the seat of the regional offices of government line agencies and of the Regional Development Council, which is charged with the function of integrated development planning for the region.

Region VII has more than 4.1 million registered voters out of the current Philippine population of 6.8 million, and as an ethnic group, the Cebuano constitute a major percentage of the country’s voting population. Hence, the Cebuano have exercised a significant influence on the national leadership. The region has produced two Philippine presidents: Sergio Osmeña and Carlos Garcia.

Cebuano's Social Organization, Traditional Customs and Culture

Many traditional customs color the life of many Cebuano even from the day they are born. Children are trained as early as possible on proper conduct, with the stress placed on obedience, respect for elders, and honesty. Some of this training has applications in daily life, like when children touch the hands of elders to their foreheads after praying the Angelus. The education of children is considered the highest priority in every family and is looked upon as the means to achieve upward social mobility. Girls are also expected to learn domestic skills like cooking, weaving, laundering, and child care to prepare them for marriage. Parents often start raising pigs once their sons reach 10 years of age to prepare for what should be slaughtered on their wedding day.

|

| Cebuano devotees singing “Bato Balani” and waving their hands in front of the Santo Niño in the religious ceremony called gozos, a highlight of the Sinulog Festival (Ariel Salupan) |

Once a man has chosen his mate, he must undergo a long process of courtship. This includes many practices that date back to pre-Christian tradition, but they are still practiced today in more remote areas though to a lesser extent. Pangolitawo or paninguha includes serenading the girl during courtship. Romance is enhanced by the recitation of love verses by the girl’s window at night or by sending billetes (love letters) through an intermediary.

The suitor visits the girl’s house with her parents’ permission, dressed in his best clothes, and bringing homemade delicacies prepared by his mother or other simple gifts for his beloved and her relatives. In the practice called pangagad, the serious suitor begins to render service at the girl’s house by helping plow the fields, fetch water, chop firewood, or feed livestock. Later on, the mamae, a respected man of the community, represents the boy’s parents and discusses arrangements with the sagang, the representative of the girl’s family. This is usually followed by a debate between the two speakers and a feast. Before the evening is over, the date of the panuyo, the visit of the boy’s family to the girl’s house, is set.

In the practice of pangasawa, the boy’s parents openly express the son’s intentions to the girl’s parents. Or the suitor may decide on visiting the girl’s house himself and begging for her hand from her parents, in the practice called pagluhud. A gift called hukut is given by the prospective groom to his bride-to-be as a sign of good faith. This is usually a ring or any precious object, which is returned if the wedding does not take place. Engagements are cancelled when the suitor’s service during the pangagad is deemed unsatisfactory by the girl’s parents or when there is a change of heart.

As the wedding day approaches, the likod-likod is held. This is a special festivity on the eve of the wedding that allows the relatives of both families to get acquainted. At this point the parents address each other as “mare” for the mothers and “pare” for the fathers. On the wedding day itself, utmost efforts are spent to beautify the bride. The bride is taken to the church, where the groom awaits her at the altar. After the ceremony, the reception is usually held at the bride’s house. During the reception, the newlywed couple, each holding a lighted candle, is led to an altar in the house where they listen to a sermon by the bride’s parents on the duties and responsibilities of husbands and wives. After the sermon, the couple rises and kisses the hands of the parents. The bride’s veil is removed, and the banquet begins. A wedding dance called alap or alussalus is held, during which the guests throw coins on a plate placed near the feet of the newlyweds as they dance. The festivities continue with more dancing and singing. A package of leftover food called putos is prepared and given to the departing guests for members of the families who were unable to attend. Other guests remain for the hugas, the practice of helping in the cleaning of the house and washing utensils after the reception.

Some folk and indigenous elements are found in the Christian marriages of Cebu. During the marriage ceremony, two candles of equal height are lighted simultaneously for peace to reign in the house of the newlyweds. The guests must not drop anything during the ceremony as this will bring bad luck. Wedding guests should not be dressed in black. The bride must step on the foot of her groom so neither will dominate the other. Upon reaching the reception, the couple is given a glass of water to drink to ensure a calm and peaceful life. The glass from which the couple drinks is thrown to the ground, and the broken pieces are not to be picked up. The bride is given a comb to run through her hair to ensure an orderly wedded life. The couple is showered with rice to assure them a prosperous life. In some towns, the newlyweds are locked up for three days in a room of the groom’s house. Meals are delivered to their room. They should not leave the house lest an evil wind blow on them.

Cebuano social organization is rooted in the family. A folk welfare society has developed out of this strong familial orientation. Kinship ties, traditionally strong, have been enhanced by the limitation of living space brought about by an unusual increase in population. The marriage rite and the events that immediately precede and follow it ensure the generation of this folk welfare society. Parents often see to it that their children by their marriages will not burden themselves, their parents, or the community. The customary bugay (bride-price) is an array of material property in the form of land, cash, animals, and so forth, mutually agreed upon, which both parents must present to each other. This dowry serves as an appreciation of the bride’s parents for having raised a daughter worthy to be the wife of any promising young man in the barrio.

During the marriage ceremony, both families attempt to outdo one another in raising the dowry. Careful planning, joyous celebration, and sumptuous eating are the hallmark of any successful wedding. However, the first few days and nights of married life are spent apart, with each one staying in his or her in-law’s house. The newlyweds may elect to reside with any of their parents until they feel that they can be independent. The bugay provides for this, and the family income may be supplemented by the husband’s wages. When substantial, the bugay may be used as inheritance for the couple’s future children. When there are several children involved, the addition of an annex to the parental house may provide a simple solution to housing problems. Married children can make their new home on a nearby lot, which enables them to look after their aging parents.

Like most other regions of the Philippines, Cebu has a generally patriarchal family system. However, in the home, the wife takes complete charge of running the household. There is a unique way of addressing people: The first names of husband and wife are joined together in a compound noun to identify the married spouses.

Folk beliefs govern the period of pregnancy, birth, and early childhood. A pregnant woman must be selective about the food she eats when she is conceiving. Dark-colored food produces a dark-skinned baby; jackfruit has a resinlike gum that may envelop the baby and hamper childbirth; twin bananas bring forth twin babies; morisquetas (boiled rice) endangers the lives of mother and child; and chicken gizzard and other heavy food cause difficult delivery.

For the sake of the unborn child, the mother observes other taboos: The child will be born with a harelip if she gazes at the sun during an eclipse; the child will be abnormal if she leaves the house without a cloth over her head or around her shoulders; the child will have a flat head if she sits directly below the lintel of the door, on heaps of palay, or on the stair steps; the child will be deformed if she talks with handicapped persons or walks over strung cord or rope; the child will be entangled in the umbilical cord if she sews; the child will choke if she carries rosaries or wears earrings, rings, and bracelets; and the child will die if she curls her hair. She should not go out when the gabilan (hawk) is about nor listen to horror stories.

The pregnant woman should take other preventive measures. When walking outside at night, she should bring suwa or biyasong (a citrus fruit) to drive away the fetus-eating wakwak, a vampire in the form of a bird. Her bedroom must have a bagakay (bamboo stick) to ward off evil spirits.

There are numerous other beliefs pertaining to mothers before, during, and after delivery. Should she be nauseous or wanting in appetite, she should step over her sleeping husband to transfer the discomfort to him. For an easy and normal delivery, no bamboo container should be covered nor any coconut-shell ladle placed crosswise on a clay jar. Killing a hen will cause bleeding during delivery. To avoid labor pains, she should not step on the rope of a grazing animal. During a first pregnancy, her stomach should be anointed with monkey’s oil to hasten delivery. She should grip the handle of a bolo to bear the pains of childbirth. Upon delivery, she should be fed a mixture of ground cacao and pulverized shell of the first laid egg of a pullet while prayers are being recited. This is so she will recover strength as quickly as a young hen after laying an egg. The placenta should be placed inside a clay pot or a coconut shell and buried under the eaves of the house for the good health of mother and child. The placenta should be buried separately so that one will not overpower the other. Thorny twigs of lemon and a bagakay should be placed around the house to safeguard the child from evil spirits.

A Christian baptism, which should ideally take place soon after the child’s birth, is regarded not only as a sacrament but as a means to keep away the malignant enkanto. The baby is customarily named after a grandparent, a deceased relative, or a saint on whose feast day he is born. Shortly before baptism, a few strands of the child’s hair are cut and the fingernails trimmed. These are placed inside a guitar or hollow top cover of a fountain pen to make the child bright and musical. The child is made to take three tentative steps before the christening so that he or she will learn to walk much sooner. During the baptism, the mother should carry a banana and a fish called lisa to protect the child from infectious diseases.

Forty days after the birth of the child, mother and child go to church for the paglahad or bendisyon. The priest approaches them with a cord tied to his waist. The mother, holding the cord, follows the priest to the altar where she kneels with the child almost throughout the mass. The ceremony is a petition for the child’s good health and long life. As the child grows, evil spirits are kept away when the mother says “pwera buyag,” especially when the child is admired.

On the occasion of death, many old practices and beliefs still persist. The deceased is untouched within an hour after death for it is believed that his or her soul is still facing the Lord. After an hour, the deceased is dressed in his or her best clothes. During the wake, the floor is left unswept to prevent bad luck. The pabaon (last prayer) is prayed at the end of the wake.

Burials are held after several days of mourning. The coffin is lifted, and the family members pass under it to prevent any misfortune from befalling them. Only after the coffin has been removed from the house may the floor be swept. In the church rites, the agoniyas (a tolling bell) signals the mourning for the dead. During the mass, family members offer something to the Lord for the soul of the departed. After the mass, they take a last look at the body. Before the casket is lowered, a sad song may be sung and the deceased is eulogized. During the burial, the relatives throw lumps of earth on the grave for the repose of the deceased. A meal may be served to parents and relatives by the family of the deceased after the burial. A nine-day novena is held for the dead, although prayers are said until the 40th day. A party called liwas is held after the novena for those who have attended the prayers. The bayanihan spirit, called alayon or tinabangay in Visayan, is best manifested during mourning as relatives and friends give donations to the family of the deceased. On the first death anniversary, all mourners’ clothes are given away and all wreaths burned. On All Souls’ Day, family members visit the cemetery.

Religious occasions are important social events in Cebu. Fiestas to honor the saints feature dances, games, and sports, and sometimes even beauty contests for civic or charitable causes. Dramas and band concerts are held in the public plazas. Cultural shows, fireworks, and the sinulog add spectacle to the Feast of the Santo Niño, which is marked in Cebu City on the third Sunday of January and is the region’s premier religious ritual. The Christmas season includes yuletide parties, caroling, and the noche buena or Christmas Eve feasts.

Video: What is Cebuano Culture? | Bisaya | BAI TV

Cebuano's Religious Beliefs and Practices

Many Cebuano, especially the less Westernized and those who live in the rural areas, continue to be firm believers in the existence of spirits. Although this belief stems from the indigenous tradition, it persists to this day and has become integrated with Catholicism.

There is a strong belief in supernatural beings who are capable of assuming any form and causing illness to those who offend them. The evil spells they cast on people can be driven away by performing rituals, reciting prayers in Spanish or Latin, making offerings, and using the crucifix and holy water. Oftentimes the folk healers or mediums like the babaylan, tambalan, and mananapit are asked to perform rituals to drive away the spirits. Spirits may appear as the tamawo, which dwells in big trees and occasionally falls in love with mortals, who upon death enter the world of the tamawo; the tumao, the creature with one eye in the middle of its face and goes out only during the new moon; the cama-cama, a mountain gnome of light brown color, whose great strength can inflict intense pain on all mortals who displease it; and the aswang, an evil being that can be disguised as a man or a woman at night, helped by its agents like the tictic and silic-silic birds.

Birds often act as agents or messengers of the spirit world. When the sagucsuc bird sings “suc, suc, suc,” it announces rain. A kind of owl, the daklap, is believed to conceal its nest on the seashore so cleverly that anybody who finds the eggs but keeps the secret becomes a curandero (healer). The hooting of the owl is considered a bad omen, specially if it comes from the roof of a sick person’s house. The appearance of the kanayas (sparrow hawk) is a portent of a coming typhoon because it is the agent of tubluk-laki, the god of the winds. Other animals also serve as good or bad omens.

Cats are often regarded as possessing special powers. Their eyesight enables them to see evil spirits. Fisherfolk and hunters use the eyes of wildcats as charms to enable them to have an abundant catch. A talisman is made from a special arrangement of a black cat’s bones. When a cat gets wet during a drought, rain is coming. On the other hand, bad weather is expected when a cat stretches itself in the morning.

Dogs become more ferocious if fed with wasps’ nests, and their continuous barking means they are seeing evil spirits like the tumao. To scare away the aswang, cow or carabao horns, or tortoise shells are thrown into red hot coals.

People recite the Ave Maria backwards to escape the poisonous sting of the alingayos (wasp). When the dahon-dahon (praying mantis) enters a house, it foretells misfortune for the occupants.

Almost all aspects of agriculture are governed by beliefs and practices. The tambalan is often called to perform the practice of bayang or buhat before virgin lands are cultivated. A dish of white chicken or white pork is offered to the unseen owner. Before planting, a table with cooked rice, chicken, wine, or buyo is set in the open and offered to the spirits, who are asked to grant a good harvest. If planting is done during a new moon in May or June, rice is toasted and then ground with sugar in a mixture called paduya. The paduya is then baked, divided into 24 parts, wrapped in banana leaves, and offered the night before planting to the aswang who protects the field. For harvest blessings, pangas may also be prepared in a basket from a mixture of rice, medicinal herbs, palm fruit, and a wooden comb.

There are practices specific to the crop being planted. During the planting of rice, one must not hurt or kill the taga-taga, an insect with protruding antennae, believed to be the soul of the palay, or else this will cause a bad harvest. A good harvest is likely when its tail points upwards. In planting corn, the first three rows should be planted at sundown, when chicken and other fowl are in their roosts. If they do not see where the seeds have been planted, they will not dig up the seeds. If it rains while the farmer is planting, it is a sure sign that the seeds will not germinate. Corn that is planted by a person with few or broken teeth will bear sparse and inferior grains.

In coconut planting, so that the nut will grow big and full, seedlings must be placed on open ground during a full moon. They should be planted at noontime when the sun is directly overhead and shadows are at their shortest. This is so the coconut tress will bear fruit soon, even if they are not yet very tall. If one carries a child while planting coconuts, the tree will yield twice as many nuts.

Bananas should be planted in the morning or at sunrise, with young plants carried on the farmer’s back so the branches will have compact and large clusters. Sticks should not be used when planting cassava lest the tubers develop fibers that are not good to eat. Ubi is a sacred root crop. lf it is dropped on the ground, it has to be kissed to avoid divine fury called gaba. The harvest of camote or sweet potatoes will be abundant if planters have laid clustered fruits on three hills.

Planters must remove their shirts, lie on the ground, and roll over several times during a full moon. Crops planted near the diwata’s place or during thunderstorms will become infested with rats.

During harvesting, if the crops are poor, the farmers prepare biku, budbud, ubas (grapes), tuba, guhang, 12 chickens, pure rice, tobacco, and tilad. These they place under a dalakit tree in the fields as offering to the spirits.

Rice harvesting entails more intricate rituals. A mixture called pilipig is prepared from seven gantas of young palay added to ubas, bayi-bayi (ground rice), grated coconut, and sugar. This mixture is pounded in a mortar and brought out at midnight. At midnight, the farmers call the babaylan to chant prayers while they surround him or her with smoke.

Fisherfolk have their own ways of soliciting the favors of the other world. During a full moon, a mananapit is asked to pray for a good catch and to bless the fishing nets and traps with herbs and incense. To cast off evil spirits, fisherfolk at sea mutter “tabi,” meaning “please allow me to fish.” They keep a small yellow copper key under their belts to protect themselves from being devoured by big fish. Divers eat the flesh of cooked turtle for greater stamina underwater. Fisherfolk avoid bad luck by neither sitting nor standing in front of their fishing gear and by returning home by way of the route used when setting out to sea. To avail of future bounty, fisherfolk using new traps must throw back half of their first catch.

That spirits who are believed to roam the world of the living must be considered in building houses. Spirits like dwelling in caves and ought not to be disturbed by the construction of a house nearby. A good site for a house is determined by burying three grams of rice wrapped in black cloth at the center of the lot. If a grain is missing when they are unearthed three days after, the site is not suitable because it will cause illness. February, April, and September are the months to build houses. To bring prosperity and peace to the owners, coins are placed in each posthole before the posts are raised. The ladder of the house should face east to ensure good health. A full moon symbolizes a happy home life when moving to a new house. For the moving family to be blessed, they should boil water in a big pot and invite visitors to stay overnight in their new house. A ritual is also performed against evil spirits during the inauguration of public buildings, bridges, and other structures.

|

| Basilica Minore del Santo Niño, Osmeña Boulevard, Cebu City (Jerry Guarino, flickr.com/jerryguarino) |

The Cebuano, like other Catholic Filipinos, are devoted to their patron saints. During fiestas, novenas are prayed, candles lit inside the churches, and the image of the patron saints kissed in homage and thanksgiving. The masses are preceded by processions to prevent misfortunes during the year. From 16 to 24 December, the misa de gallo (dawn mass) is held for nine consecutive days. There are also solemn Lenten rituals, long processions, and religious dramas.

Christian folk religiosity is most apparent and typical in the Lenten procession held on Holy Thursday and Good Friday in Bantayan Island. In this major Lenten spectacle, the Bantayanon garb their children in angel and saint costumes and follow the carriages of their favorite saints. Apart from the life-size statues of San Vicente, San Jose, Santa Teresa, San Pedro, and Santa Maria Magdalena, there are around 20 other floats depicting scenes from Christ’s passion.

|

| A candlelit procession during the feast of Santo Niño in Cebu (The Philippine Star) |

Their most popular devotion, however, is to the Santo Niño of Cebu, whose statue, venerated in the Augustinian Church in Cebu City, is the oldest Christian religious relic in the Philippines. The Holy Child is believed to be a savior during fires and natural calamities. It is a performer of miracles big and small; its role can range from shielding the island from foreign invaders in earlier times to playing harmless pranks.

Both secular and religious authorities have symbolically linked the story of the icon’s discovery in the 16th century with the nation’s history. A grand, weeklong celebration during the feast of the Santo Niño is highlighted by sinulog dances and a candlelit, evening procession.

The Cebuano Community

In pre-Hispanic times, what would later become the city of Cebu was a lineal settlement by the sea—a cluster of rather large but not too populous barangays and a port. This roughly encompassed the six-hectare area bounded by the present-day streets of Magallanes, Juan Luna, Manalili, and Martires. Here stood variations of the Cebuano nipa hut that still characterizes rural Cebu.

The native hut is basically divided into two sections: the sala, a hall combining living, dining, and sleeping quarters, and the abuhan or cocina (kitchen). However, the local dwelling may have a third section, the sulod, a room for sleeping and storage. Sometimes a porch graces the entrance, leading into the sala. Tropical weather requires walls of light materials such as coconut or nipa ribs, buri palms, cogon grass, and bamboo; floors of bamboo slats with gaps between them; awning-type windows; and low room dividers. Evident are features of other lowland Filipino houses as distinct from upland houses: the use of natural lumber instead of hewn timber, rattan, or vines to hold the building materials together, and long poles dug deep into the ground to support the roof.

|

| Cebuano nipa dwelling and tobacco drying on rack, 1933 (CCP Collections) |

Precolonial houses were built near rivers, fields, or forests. Farmers also erected makeshift structures called balai-balai or bugawa, in their fields. When the Spaniards arrived, native settlements were transformed by the reduccion policy, concentrating the natives in organized pueblos (towns), a landmark of Spanish colonization. In the Cebu port area, the natives were moved to San Nicolas, a town south of the Pagina River. This came to be identified as “Old Cebu” to differentiate it from the original center, which was converted into the colonial city of San Miguel. The Spaniards lived within a triangular settlement composed of the Augustinian church, the convento, and Fort San Pedro, which is the first colonial building constructed in the Philippines in 1565. Both the city plans of 1699 and 1738 picture a rectangular grid system of square city blocks. By the 17th century, churches, convents, and colonial-style houses surrounded the main plaza, Maria Cristina, now Plaza Independencia. The 18th-century city had formidable edifices and wide-open spaces, and was encircled by arrabales (suburbs) for native dwellings. Thus to the west of the poblacion de europeos (settlement of Europeans) called Villa de San Miguel or ciudadde Cebu, lay the poblacion de naturales (settlement of natives) of San Nicolas. To its north and linked to the sea by an estuary lay the old Chinese ghetto called the Parian.

The Parian emerged from Spain’s policy of ethnic segregation. It was established in 1590 when Cebu began its brief participation in the galleon trade. Initially a market and trading center, it grew into a residential district of mestizos or half-breeds possessed of landed wealth and absorbed into Hispanic culture. The stature of the Parian as trading center diminished in the 19th century with the shift of port activities and the Chinese population to the district of Lutao in Cebu City.

The street patterns of the Spanish city partly correspond with the present street locations, particularly in the southeast corner of Cebu City. Legaspi and Gomez Streets have retained their names; Magallanes was the south shoreline, MacArthur Boulevard was the north-south; Juan Luna was Felipe II; Gullas was Nueva; M. J. Cuenco was Martires; Jakosalem was Norte America.

Early Spanish houses in Cebu were of tabique, that is, walls of bamboo or boards, reinforced by a lime-and-sand mixture. The 19th century gave rise to the bahay na bato house of stone, brick, and wood. Besides fireproof measures, frames of wooden posts reinforcing the exterior walls are added in anticipation of an earthquake. A typical house has a brick-and-stone first level and a predominantly wooden second level, with sliding windows adorned with lampirong or capiz shell (Placuna placenta) panes. Floors are hardwood planks set on huge beams. In earlier times, the ground floor would often be uninhabited because of the damp ground; a portion of it could be raised above the ground as an entresuelo (mezzanine) serving as an office or servant’s room. The upper story contains the house proper comprising a caida (spacious hall), comedor (living and dining rooms), comun (toilet), baño (bathroom), and cocina. The azotea at the side of the house is a modification of the native batalan or pantaw. As in other parts of the country, the bahay na bato in Cebu has a sloped roof, wide eaves, profuse windows, high ceilings, broad halls, and raised floors.

Now a public museum and administered by the Ramon Aboitiz Foundation, Casa Gorordo, which is located at the corner of Lopez Jaena and Ballesteros in the Parian district, represents this style as adapted for a moderately wealthy residence of the period. More imposing bahay na bato were those owned by Don Mariano Veloso at the corner of Juan Luna and Martires, fronting Plaza Independencia; Don Manuel Cala on Juan Luna; and Don Pedro Cui on Sikatuna in Parian. These houses have not survived. Rare was the full stone house, such as the partly extant 18th-century Parian residence of the Jesuits.

The Spaniards left a considerable architectural legacy in Cebu. Notable landmarks are the Santo Niño Church, Cebu Cathedral, Recoletos Church, and the churches of Argao, Bantayan, and Carcar, St. Catherine’s School, the Emergency Hospital and Dispensary building in Carcar, and the forts in Daanglungsod and Boljoon.

|

| Casa Gorordo (Photo by Mark Anthony Maranga) |

|

| Casa Gordo interior (Cebu, Pride of Place by E. Billy Mondoñedo. Arts Council of Cebu Foundation, Inc., 2007) |

Cebu City acquired a cosmopolitan character in the 20th century. In the first quarter of the century, the city abounded with foreign establishments, such as the Chinese Yap Anton and Co., the Japanese Bazaar Sakamoto, the Indian British Indies Bazaar, the Spanish Muertegui y Aboitiz, the American Bryan and Landon Co., and the German Botica Antigua. Firms were generally situated together according to the type of business. Export and shipping firms lined the port area, and Colon Street (formerly Calle del Teatro) featured the cinemas Oriente (formerly Teatro Junquera), Empire, and Royo. Although the seat of the city government has shifted several times, it has always remained in the original Spanish ciudad.

The city was renewed by the Philippine Commission’s 1905 urban program. Streets were realigned, widened, and straightened out; new buildings given a special elevation; sidewalks cemented and uniformed. San Nicolas merged with the city proper in 1901. The American era also saw modern landmarks and structures, including Fuente Osmeña, Jones and Mango Avenues, and the upmarket residences in the new suburbs of Sambag, Cogan, and Lahug. Transport and communication improved remarkably with the construction of a line of the Philippine Railway Company, later destroyed during World War II. The Parian shrank and eventually lost its aristocratic quality. Fires changed the face of the city as the downtown area was razed in 1898, 1903, and 1905.

The postwar period saw the further expansion of the city as outlying areas were integrated into the metropolis. Factory sites and residential areas developed to the south, north, and west of the city. Rolling, elevated areas west of the city were carved out as new residential subdivisions, such as Beverly Hills and Maria Luisa Estate; and the city shoreline was reclaimed in the Cebu North and South Reclamation projects to create space for new urban development. Today, Metropolitan Cebu consists of seven cities—Carcar, Cebu, Danao, Lapulapu, Mandaue, Naga, and Talisay—and six municipalities—Consolacion, Liloan, Compostela, Cordoba, Minglanilla, and San Fernando.

Churches continue to be major architectural landmarks in the postwar period. In addition to the old churches that survived the war, like the Santo Nino Church and the Cathedral, postwar churches include the new Recoletos Church, Redemptorist Church, Santo Rosario Church, Sacred Heart Church, and Lourdes Church in Punta Princesa. Joining a few surviving prewar structures like Vision Theater on Colon Street, modern commercial and residential buildings were erected, among them the Cebu Plaza Hotel, Robinsons Department Store complex, and Metrobank Building on Fuente Osmeña. Restored and repurposed as museums are the old cathedral rectory and the 19th century carcel or jail.

In the 1990s, with the establishment of the Cebu Business Park and the development of the Cebu Reclamation Area, there was an upsurge in urban development, thus causing the architectural face of the city to change at an even faster rate. However, architecture in Cebu confronted several challenges. There was the problem of underutilized local talent, since many buildings were put up by Manila-based corporations that hired Manila-based principal architects, thereby reducing their Cebuano colleagues to mere supervisory roles. On the other hand, there was a growing sense of self-awareness as a community on the part of Cebuano and Cebu-based architects. This had been fostered by local schools of architecture like the University of San Carlos and Cebu Institute of Technology, by professional associations, and by the work of such pioneering Cebuano architects as Santos Alfon, Cristobal Espina, and Filomena Perez-Espina. Cebuano architects were not only taking an active part in local urban planning but had taken a more visible and decisive role in the design of new buildings. Young Cebuano architects were coming into their own and aimed to make their own distinctive contribution to the architectural profession in the Philippines.

By the turn of the 21st century, economic advancements and the surge in real estate and service industries had brought rapid growth to urban planning and architecture in Cebu. After the establishment of the Ayala Center Cebu mall in 1994, Ayala Land’s affiliate, Cebu Holdings, developed the Cebu Business Park. Today, 15 high-rise buildings stand on a 50-hectare area along Archbishop Reyes Avenue. In 2001, the Cebu Information Technology Park was constructed on a 24-hectare lot in Lahug. Developed by the Cebu Property Ventures and Development Corporation, the business complex has brought information technology firms to Cebu and opened the job market for BPOs to workers from the Visayas and Mindanao.

These business and residential parks have drawn thousands of young professionals from the Visayas and Mindanao into Cebu, as bridges and flyover roads were erected across the city, and new commercial spaces constructed in Talamban, Apas, Kamputhaw, Guadalupe, and Kasambangan.

The Cebu provincial government spent 800 million pesos to construct a three-story convention center in Mandaue City, which became the venue for the 12th ASEAN Summit and the 2nd East Asia Summit. However, this Cebu International Convention Center was met with controversy for its high cost and relatively short construction schedule of one year. The convention center opened in 2007 in time for the international summit. Damaged by an earthquake and a typhoon, the convention center would be up for sale seven years after its inauguration.

Today, one of Cebu’s largest community development projects is the South Road Properties (SRP), a vast 300-hectare area that the city government envisions to become a site for retirement facilities, midrise residential complexes, business establishments, a hospital, and a UP campus. After its initial phase in 2009, the new SRP Bridge overlooking the property now links Cebu City to Talisay and Minglanilla. A seaside retail complex owned by Henry Sy will be constructed in the area and is projected to become the largest commercial center in Cebu.

Sy donated a portion of the area to the Archdiocese of Cebu for the construction of the Chapel of San Pedro Calungsod, the first Visayan saint who was canonized in 2012 by Pope Benedict XVI. Carlos Arnaiz, a US-based architect, designed the chapel in the contemporary style. Made of glass, stone, and sand, the chapel stands on a 5,001-square meter lot and has 100 walls of varying width and height. For the occasion of Calungsod’s canonization, the Archdiocese of Cebu built another structure made of bamboo and steel. The shrine, which overlooks the SRP Bridge, stands out for its facade that is shaped into palm fronds.

The University of San Carlos Talamban constructed Cebu’s first energy-saving building. The 16,000-square meters Joseph Baumgartner Learning Resource Center, which houses the Cebuano Studies Center, among other libraries and study halls, is one of the largest libraries in the country. Brother Antonio Flores SVD, designed the four-story structure with architects Jensen Racho, Kimberly Yung-Gultia, and Richeto Alcordo of the University of San Carlos. The interiors are brightened by high ceilings, and wide glass windows allow natural light to stream in.

Arts and Crafts of Cebu

Cebu’s liturgical art manifests its deeply rooted Catholic tradition. Relief or three-dimensional santos (holy images), murals and paintings for altarpieces, gold and silver vestments, and altar accessories have always been Cebuano expressions of religiosity that are stylistically similar to those of Bohol.

Cebuano folk art includes basketry and the handcrafting of jewelry and musical instruments. Basketry was developed by the interisland trade, which regularly demanded cargo containers. Baskets and planters are made of coco midrib, rattan, bamboo, or sigid vine. The island’s furniture industry is related to this art. Chairs of rattan and buri ribs are fashioned using basket-weaving techniques. Cebu has produced some of the most sought-after furniture makers in the world. Kenneth Cobonpue’s acclaimed work on rattan furnishings shows a mastery of new techniques. Allan Murillo of Murillo Furniture Philippines in Inayawan Pardo specializes in custom-made wood and metal furniture known for its craftsmanship and sophisticated design.

|

| Living room chairs in Yoda style designed by Kenneth Cobonpue (Photo courtesy of Kenneth Cobonpue) |

Mactan produces guitars and ukuleles from langka (soft jackfruit wood). Cebu’s abundant shells and coral can be transformed into ornaments, some of which are set with precious metals. Popular Cebuano arts of the 19th century, such as sinamay weaving, dyeing, and pottery, especially the alcaaz or water jars of fine red clay, have since declined. Such is the creativity of local artisans, however, that new crafts such as stoneware are constantly being developed.Mat Weaving

Painting was the first secular art that appeared in the mid-19th century. Initially unsigned and undated, they were personal rather than professional. Gonzalo Abellana of Carcar, Canuto Avila from San Nicolas, Raymundo Francia of Parian, and Simeon Padriga were early painters and sculptors who actively participated in the period of transition from religious to secular art.

|

| Sofronio Y. Mendoza, Untitled, 1979 (Photo courtesy of Leon Gallery Fine Arts and Antiquities) |

Aside from their works, Cebuano masterpieces include Diosdado “Diovil” Villadolid’s finger paintings, Oscar Figuracion’s paintings of the Blaan community of Davao, Julian Jumalon’s lepidomosaic art, Silvester “Bitik” Orfilla’s historical mural titled Ciudad del Santisimo Nombre de Jesus (City of the Most Holy Name of Jesus), and Carmela Tamayo’s tartanilla series.

Aside from these painters, others contributed to the flourishing of Cebuano visual arts in the 20th century: Mary Avila, Jose Alcoseba, Vidal Alcoseba, Virgilio Daclan, Sergio Baguio, Emeterio Suson, and Jesus Rosa.

|

| Martino Abellana, Boy with Instrument, 1972 (Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas Collection, photo courtesy of Sister Gemma Abellana) |

Martino Abellana is the “dean of Cebuano painters.” Though primarily a figurative impressionist, his later works nevertheless show a desire to reconcile the figurative and the abstract. Notable works of his are The Farmer’s Son, Job Was Also Man, Rocks, and Korean War. Cebu and the Central Visayas have also contributed to the Manila art scene through artists such as Manuel Rodriguez Sr. and National Artist Napoleon Abueva, who are distinguished for their pioneering ventures in Philippine graphic arts and modernism in sculpture, respectively.

An important catalyst in the development of the Cebu art scene was the founding of the Cebu Arts Association (CEARTAS) in 1937 by Julian Jumalon, in association with artists like Oscar Figuradon, Jose Alcoseba, Emilio Olmos, and Fidel Araneta. CEARTAS promoted community awareness of the visual arts as well as the exchange of ideas among artists.

In the post-World War II period, the older practitioners were joined by younger artists like the Mendoza brothers (Sofronio, Teofilo, and Godofredo), Romulo Galicano, Gamaliel Subang, Fatherr Virgilio Yap, Jose Yap Jr., Tony Alcoseba, Gig de Pio, and Mardonio Cempron. Some of these artists, notably Sofronio Y. Mendoza, also known as SYM, and Romulo Galicano, later moved to Manila and to foreign countries to gain a much wider reputation and audience.

Today, Cebu has what is probably the largest community of artists outside of Manila. Although many of the young practitioners have inherited the Cebuano artist’s predilection for landscapes in the Abellana style, they are also influenced by various modern styles in the country, like those of Jose Blanco of Angono and the late Vicente Manansala, as well as from abroad. Today’s crop of artists includes Isabel Rocha, Mariano Vidal, Boy Kiamko, Fred Galan, Wilfredo Cuevas, Manual Panares, and Rudy Manero. Anthony Fermin, Paulina Constancia Lee, and Celso Pepito are also influenced by modernism. The town of Carcar, hometown of Martino Abellana, has produced a new generation of artists led by Gabriel Abellana, Martino Abellana Jr., and Luther Galicano.

The opening of the fine arts program at UP College Cebu, the first formal fine arts school south of Manila, has dynamized the Cebuano art scene. Soon after its founding, Manila Artist Jose Joya initiated in 1978 the Annual Joya Art Competition, which has showcased new talents from UP Cebu, such as Raymund Fernandez, Javy Villacin, Edgar Mojares, Arlene Villaver, Janine Barrera, and Karl Roque. The University of San Carlos, whose own fine arts program opened in 1985, has recruited artists such as Jorge Lao, Radel Paredes, and Paul Vega.