Unang Bahagi: Dulo ng 1500s at Maagang bahagi ng 1600s

Bilang bahagi ng kasaysayan ng Pilipinas, narito ang isang serye kaugnay sa pagunlad ng mga kasuotan sa Maynila (at sa Pilipinas) mula noong ika-16 na siglo (1500s), hanggang sa kalagitnaan ng ika-20 na siglo (1900s).

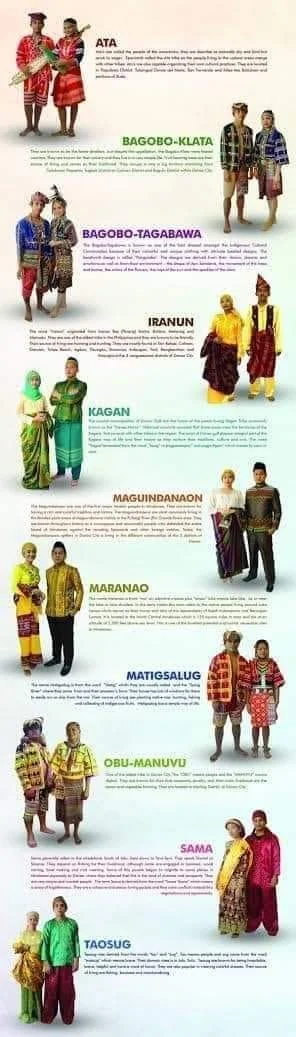

Pananamit NG Mga Sinaunang Pilipino

Ang pananamit ng mga sinaunang Pilipino ay lubhang naiiba sa pananamit ngkasalukuyan. Noon, ang mga lalaki ay nakabahag ngunit may kanggan, na pang-itaas, na maikliang manggas at itim o asul na kamisang walang kuwelyo. Ang kulay ng kamisa ang nagpapakilala kung ano ang antas o ranggo ng nagsusuot noon: kung pula ay nangangahulugangdatu ang may-suot; kung asul o bughaw o kung itim ay nabibilang sa uring mababa kaysa datu.Sa kabilang dako, ang pananamit ng mga babae ay binubuo ng pang- itaas na kung tawagi‟y baro at ng pang- ibaba na kung tawagi‟y saya. Sa Kabisayaan, ang tawag dito‟y patadyong.

Ang istilo ng pananamit at pang-unawa ng mga Pilipino sa makabagong panahon ay naimpluwensyahan ng kanilang mga katutubong ninuno, ang mga kolonisador ng Espanya at ng mga Amerikano, na pinatunayan ng kronolohiya ng mga pangyayaring naganap sa kasaysayan ng Pilipinas.

Noo‟y walang sapatos ang mga tao, kaya‟t ang lahat ay nakatapak. Gayunman, ang ulo‟ymay putong, na anupa‟t isang kayong damit na nakabilibid sa ulo. Sa kulay ng putong nakikilalaang “pagkalalaki”: kung pula ang putong, ang may -suot ay nakapatay na ng isang tao; kung mayburda ang putong, ang may-suot nito ay nakapatay na ng maraming tao. Ang mga babae ay hindinaglalagay ng putong, ngunit ang kanilang buhok ay nakapusod.

Tara at silipin ang tila mga "fashion scrap book" at "cut outs" na mga pahina.

Tagalog Royal Fashion

(Late 1500s to Early 1600s)

The outfit featured here was inspired by the illustrations of the Boxer Codex, a book from 1600 that features illustrations of early colonial indigenous societies.

Ikalawang Bahagi: Kalagitnaan ng 1600s o Ika-17 na Siglo (17th century)

The second part of our series presents fashion in Manila during the 1600s or 17th century, in the first century of Spanish rule. It shows both Spanish and native fashion.

Isang serye kaugnay sa pagunlad ng mga kasuotan sa Maynila mula noong ika-16 na siglo (1500s), hanggang sa kalagitnaan ng ika-20 na siglo (1900s).

Sa ikalawang bahagi ng ating serye ng paskil ukol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila, ating bibigyang tutok ang mga kasuotan noong unang siglo ng pananakop ng mga Espanyol.

Narito ang ilang guhit upang magbigay ng ideya kaugnay ng mga kasuotan ng mga Kastila at mga katutubo sa Maynila.

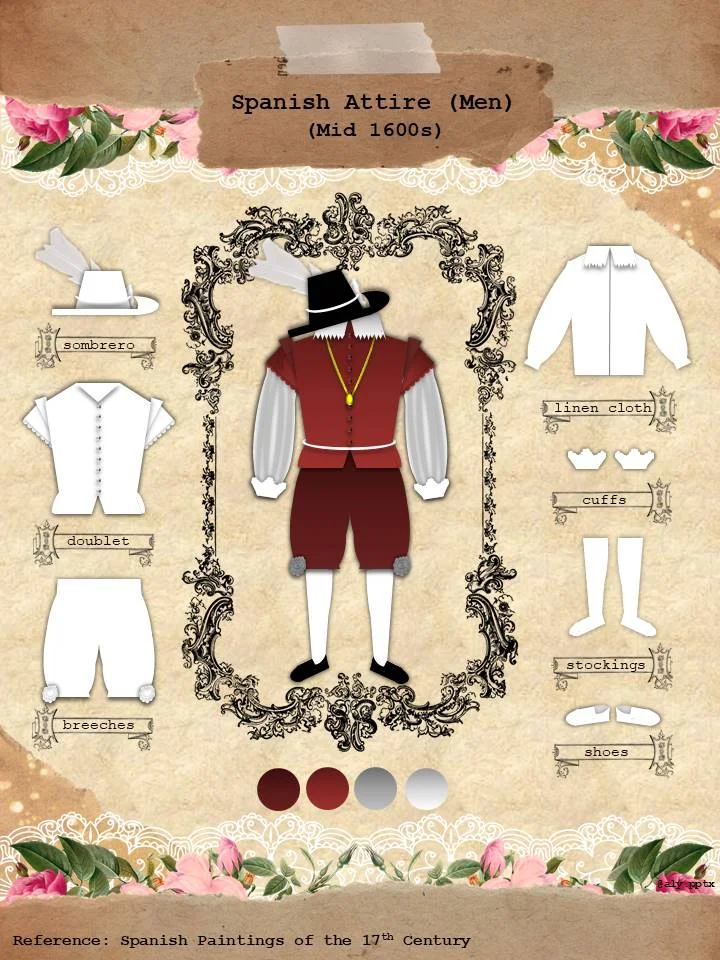

Spanish Attire for Men (mid-1600s)

Due to the lack of readily available visual references, this artwork was based mainly on Spanish paintings from the period, including those by Diego Velasquez. It shows a more or less average attire, with the important parts. Of course, these costumes varied depending on the wealth and social standing of the individual.

Basic parts included the doublet, which was carried over from the 16th century. These would be replaced by loose shirts and long coats by the last part of the 17th century. The ruffs of the 16th century were replaced by linen and silk collars. Breeches were worn together with stockings and shoes.. When travel and outdoor activities were involved, riding gloves for the hands and leather boots would have been worn, with spurs should one be riding horses. Cavalier hats, broad-rimmed hats with feathers and ribbons, were also worn. Swords were also worn and carried around, together with sashes and capes.

As for hairstyles, hair up to the neck was fashionable in the early part of the 17th century, but would soon be replaced by longer hair by the middle of the 1600s. Long curly wigs would become fashionable by the end of the 167th century.

Spanish Attire for Women (mid-1600s)

Due to the lack of readily available visual references, this artwork was based mainly on Spanish paintings from the period, including those by Diego Velasquez. It shows a more or less average attire, with the important parts. Of course, these costumes varied depending on the wealth and social standing of the individual. There would have also been variations due to climate conditions.

The bodice worn on top had a corset which gave the wearer the fashionable silhouette. The lower half of the dress consisted of the hoop skirt or the guarda infante which a carry-over from the Renaissance, although it stayed fashionable in Spain well into the 17th century.

Hairstyles varied but mostly involved long curls, up to the shoulder, or were bunched together and kept by ribbons with floral decorations.

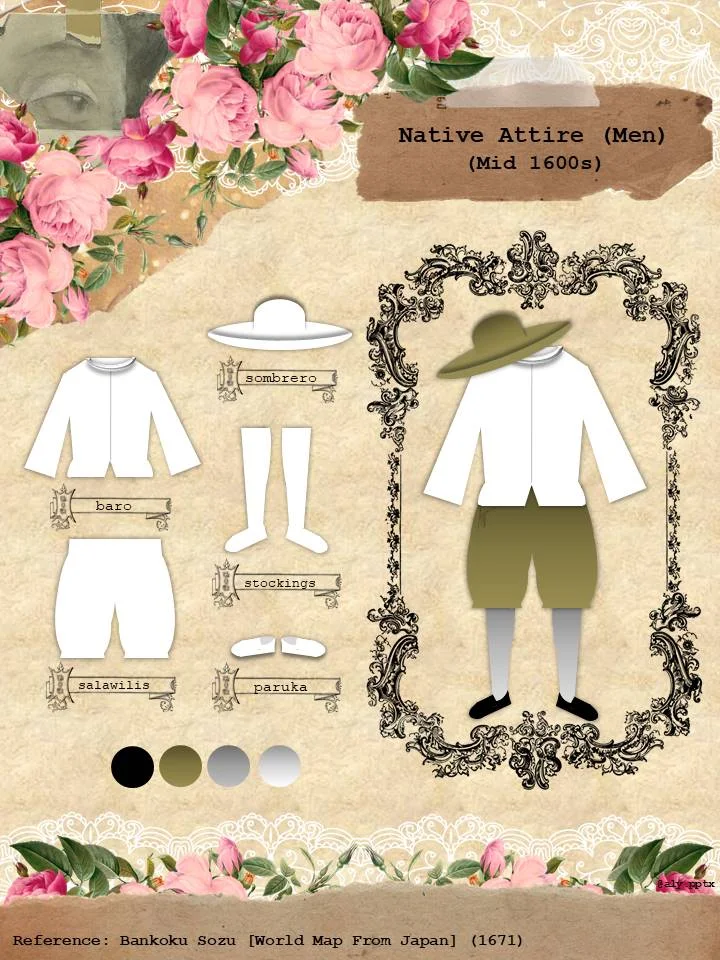

Native Attire (Men), the mid-1600s

This artwork was based on the Bankoku Sozu, a world map from 1670 Japan which also featured illustrations of people. In addition to this several journals in the 17th century, Manila also provided textual reference.

By the 1600s, natives in Manila were already copying Spanish attire, replacing g-strings with breaches and loose shirts. Putongs or headdresses were also being phased out in favor of hats, although it must be noted that natives already possessed several types of hats prior to colonization.

Some wore stocks and shoes, indicative of class, but for the majority, they would have gone barefoot.

Native Attire for Women, (mid-1600s)

This artwork was based on the Bankoku Sozu, a world map from 1670 Japan which also featured illustrations of people. In addition to this several journals in the 17th century, Manila also provided textual reference.

Women's attire in Manila still shows resemblance to attires from the 1500s. However, the details were becoming simpler, although the pieces were still the same.

Ikatlong Bahagi: Kalagitnaan ng 1700s o Ika-18 na Siglo (18th century)

Ang ikatlong bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga ksutan sa Maynila ay dadalhin tayo sa kalagitnaan ng ika-18 na siglo o 1700s. Narito ang ilang guhit upang magbigay ng ideya kaugnay ng mga kasuotan ng ilan sa mga mamamayan ng Maynila, gaya ng mga mestizo at Kastila. Ang mga kasutoan ay ibinatay sa ilang dibujo, kagaya ng mga guhit sa Mapang Murillo Velarde at Bagay, at mga dibuho mula sa Tsina.

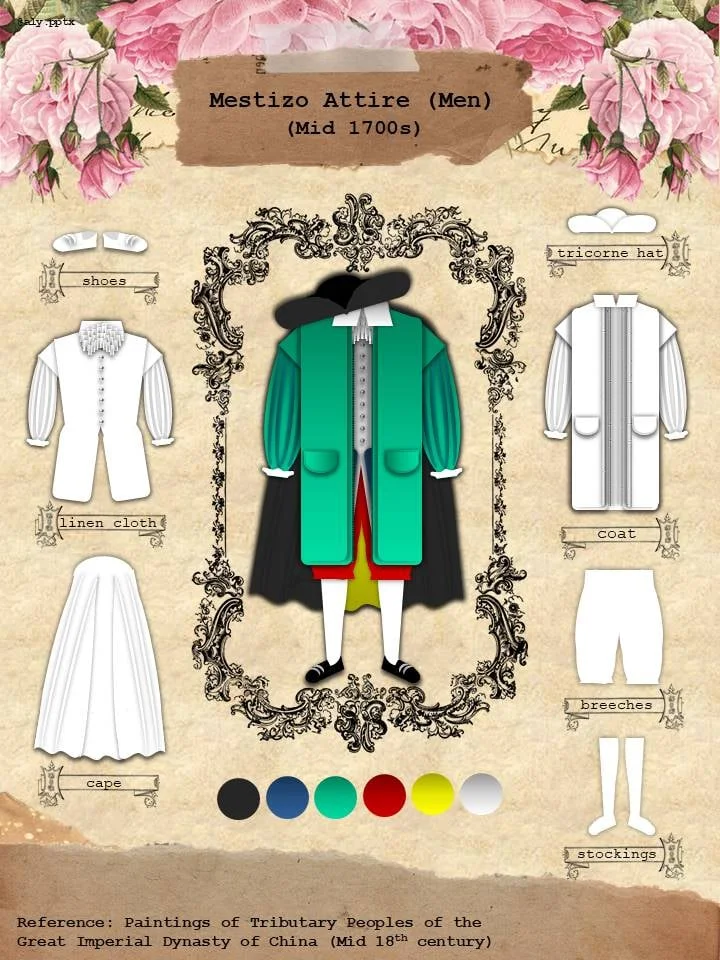

Spanish and Mestizo Attire for Men, (mid-1700s)

Reference: Paintings of Tributary People of the Great Imperial Dynasty of China

Men's fashion in the middle of the 18th century had evolved from the tight doublets of the 15th and 16th century, into long and loose coats. The iconic hat of the period was the tricorne hat or the tres picos hat which was a hat with its brim held in such a way that it had three points. Men wore wigs. wigs in the late 1600s to the early 1700s were longer, but by the middle and up to the end of the 1700s, the powdered wigs became shorter, featuring side curls and a ponytail.

Spanish and Mestiza Attire for Women, (mid 1700s)

Reference: Paintings of Tributary People of the Great Imperial Dynasty of China

Women's attire in Manila echoed those in Europe as well as Mexico, although these were interpreted with local materials to adjust to the climate. This illustration features a bodice with a low neckline, and with sleeves up to the elbows and decorated with laces. The hair was worn and kept up, and decorated with ribbons and other materials.

Spanish and Mestizo Attire for Men, (mid 1700s)

Reference: The Murillo Velarde - Bagay map.

As the previous slide, this attire features the tricorne hat, long coats, capes, and breeches up to the knees.

Explainer:

Unless a source from the period directly says Tricorne or Tricorno, the proper term is "cocked hat" - it is a round wide-brimmed hat that is 'cocked'.

While early 18th-century frock coats were fairly long they did not have a cape automatically attached to them. That would be worn by a cord at the neck and hung down the back of one of the sides.

The actual style of a frock coat from the period would be thus:

Native Attire for Women, (mid-1700s)

Reference: Murillo Velarde - Bagay Map

Native women's attire was still similar to those worn in the previous century, which in terms could be seen as simpler versions of those worn in eh 16th century.

Spanish and Mestizo Attire for Men, (mid-1700s)

Reference: Paintings of Tributary People of the Great Imperial Dynasty of China

Men's fashion in the middle of the 18th century had evolved from the tight doublets of the 15th and 16th century, into long and loose coats. The iconic hat of the period was the tricorne hat or the tres picos hat which was a hat with its brim held in such a way that it had three points. Men wore wigs. wigs in the late 1600s to the early 1700s were longer, but by the middle and up to the end of the 1700s, the powdered wigs became shorter, featuring side curls and a ponytail.

Explainer:

The proper term is 'cocked hat' - 'tricorne' is a modern term.

I doubt that this style (which is more mid 17th century NOT mid-1700's - could this be a typo) would still be in vogue even in the colonies by the MID-18th Century. At best you would see "Louis XIV/Peter the Great"-era styles. The Bourbon monarchy which took over after the War of Spanish Succession began a modernization program that reached its zenith under Carlos III and this would have affected clothes as well.

This is F.R.Hidalgo's painting of the assassination of Governor-General Bustamante in 1719. The clothes here are representative of the War of Spanish Succession Era moving on toward the ACTUAL Mid 18th Century. You have longer waistcoats and frock coats which will slowly but inexorably shorten as the century moves on. You have knee breeches that are less baggy and more form-fitting.

Linen shirts were not button up all the way as depicted, they had an opening for the neck and head that went probably down to the bottom of the chest which, if one was wealthy, would have ruffles and lace and could be closed at the neck. Cuffs would have ruffles and lace if one was rich or be plain but flared if not.

Everything about the infographic points to the middle of the 17th century, not the mid 18th century. Or maybe the Chinese source got their information wrong.

Spanish and Mestiza Attire for Women, (mid 1700s)

Reference: Paintings of Tributary People of the Great Imperial Dynasty of China

Women's attire in Manila echoed those in Europe as well as Mexico, although these were interpreted with local materials to adjust to the climate. This illustration features a bodice with a low neckline, and with sleeves up to the elbows and decorated with laces. The hair was worn and kept up, and decorated with ribbons and other materials.

Comments:

No western/westernized woman would be caught dead wearing BREECHES. Women did not have panties, bloomers, or any sort of lower underwear until something like the middle of the 19th century.

Ikaapat na Bahagi: Kalagitnaan ng 1800s o Ika-19 na Siglo (19th century)

Ang ikaapat na bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila ay tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa siyudad noong unang kalahat at kalagitnaan ng 1800s. Ang kagandahan sa panahong ito ay marami nang mga mapagbabatayan na mga dibuho at mga likhang sining na isinasalarawan ang mag kasuotan at ang mundo ng Maynila noong 1800s.

Native Attire for Women (mid-1800s)

Although the look and composition of Native wear remained similar to that from the 18th century, changes did occur in terms of the figure as well as materials available due to the opening of Manila's ports (to be followed by other port cities in the country).

Mestiza Attire for Women (mid-1800s)

The 1800s saw Manila's ports being opened to wider international trade and commerce. This allowed the principalia and the mestizo elite to engage in business as well as access materials and the latest fashion trends from Europe. The mestizos adopted European silhouettes using native materials, augmented by imported fabrics such as those from Britain.

Native Attire for Men (mid 1800s)

Although the look and composition of Native wear remained simial to that from the 18th century, changes did occur in terms of the figure as well as materials available due to the opening of Manila's ports (to be followed by other port cities in the country).

The man in this drawing is shown wearing a rain cape, known as an esclavina.

Native Attire for Men (mid-1800s)

Although the look and composition of Native wear remained simial to that from the 18th century, changes did occur in terms of the figure as well as materials available due to the opening of Manila's ports (to be followed by other port cities in the country).

The illustrations here show an individual carrying a rooster, since cockfighting and having one as a companion, was already widespread in the past. The other individual is an affluent native, whose fashion is similar to those worn by the mestizos of mixed descent.

Mestizo Attire for Men (mid-1800s)

The 1800s saw Manila's ports being opened to wider international trade and commerce. This allowed the principalia and the mestizo elite to engage in business as well as access materials and the latest fashion trends from Europe. The mestizos adopted European silhouettes using native materials, augmented by imported fabrics such as those from Britain.

The ancestor of the barong was widely worn by many of the mestizo elite. These barongs feature elaborate cuffs and collars. Top hats were also favored. This will change as more people were able to go to Europe.

Native Attire for Women (mid 1800s)

Although the look and composition of Native wear remained similar to that from the 18th century, changes did occur in terms of the figure as well as materials available due to the opening of Manila's ports (to be followed by other port cities in the country).

The illustration shows a native woman from the countryside and a more affluent native.

Ikalimang Bahagi: Huling Bahagi ng 1800s o Ika-19 na Siglo ( End of the 19th century)

PANAHON ng TRANSPORMASYON at REBOLUSYON

Ang ikalimang bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila ay tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa siyudad noong huling bahagi ng 1800s. Tulad ng naunang "post" tungkol sa unang bahagi ng 1800s, ang panahong ito ay sagana sa mga larawan at mga likhang sining na maaaring magamit bilang reference.

Ang huling bahagi ng 1800s ay katatangian ng transpormasyon sa Maynila at sa bansa, tulad ng paglago ng ekonomiya, pagdating ng mga makabong teknolohiya, pag-ahita para sa mga karapatang sibil at sa kalaunan ay digmaang rebolusyonaryo laban sa Espanya at kalaunan ay digmaan laban sa Estados Unidos.

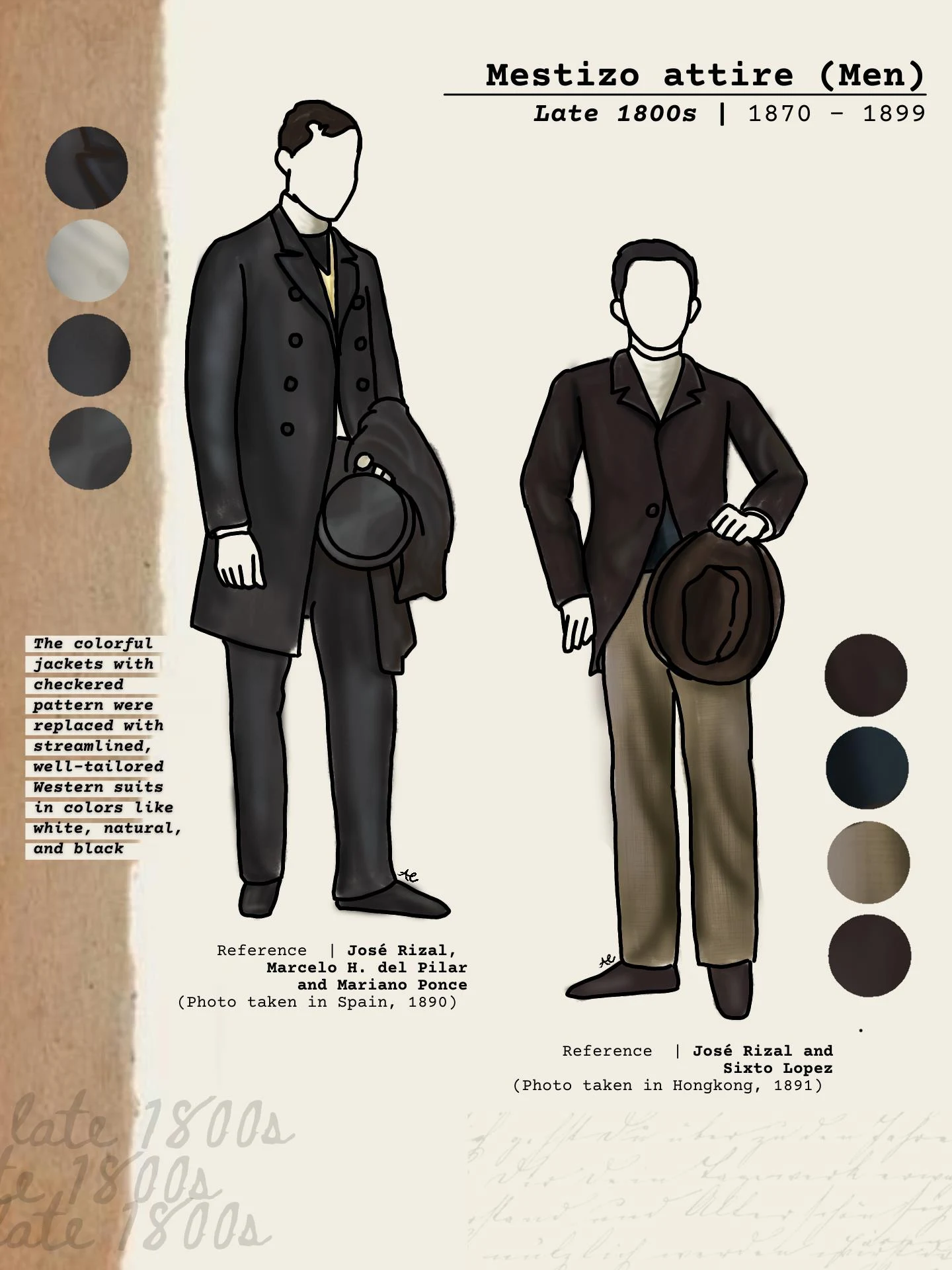

Mestizo Attire for Men, late 1800s

As more of the prinicipalia and the ilustrados went abroad, they were exposed to the fashion trends in Europe, As a result, men's fashion in Manila and amongst the elite gradually became European in style and make. Numerous tailors and haberdasheries would spring up in Manila.

These ilustrados would not only bring European fashion with them. They also brought liberal ideas for much-needed reforms, such as civil liberties and political rights. Spanish apathy for colonial reforms would eventually lead to an armed revolution.

Mestiza attire of the late 1800s

The traje de mestiza.

The baro't saya evolved into the traje de mestiza, which would come to be known as the Maria Clara dress.

It was a hybrid of European-inspired style and construction but with native materials and ornamentation.

The early 1880s would see the use of the bell or bishop's sleeves. Hair ornamentations included the payneta and fantoches or decorative hairpins.

Mestiza attire, late 1800s

By the 1860s to the 1870s, flared skirts with the help of petticoats and stiff abaca facing became a trend. This mirrored the Victorian style of the period.

Mestiza Attire, late 1800s

While seemingly similar to the fashion of the mid-1800s, the late 1800s would witness changes in the form of women's dresses. The basic elements still included: the baro, saya and panuelo or tapis. On the other hand, the Spanish elite preferred European women's fashion.

Native Attire for Women, late 1800s

Native women's attire remained relatively unchanged, due in part to poverty and other hardships. Women of the period were able to find employment as ambulant vendors, food merchants and even as factory workers in the many tabacaleras of Manila.

Revolutionary Uniforms, late 1800s

In 1896, the Philippine revolution broke out. Nearby provinces around Manila erupted rose in revolt, marked by ambuscades, state reprisal, and pitched battles like those in Cavite. For the most part, the revolutionaries wore civilian attire. But as Spanish fortunes fell, especially with the advent of the Spanish-American War in 1898, droves of native infantry joined the revolution.

The soldiers wore the rayadillo (but not the civil guards who wore blue uniforms). The rayadillo was made of light fabric, which was made for Spanish troops stationed in Cuba and Asia. The rayadillo worn by the Spanish army was different from the rayadillo of the First Philippine Republic. The uniforms worn today by guards in Intramuros are patterned after the rayadillo of Spanish troops.

Revolutionary and Republican Uniforms, 1898-1902

Part of the army reforms instituted by the new revolutionary government and the First Philippine Republic, was the creation of new uniforms for officers and men of the armies of the Republic. They built upon existing Spanish traditions and thus were born the Filipino rayadillo. This was recently made famous by movies such as Heneral Luna and Goyo. Officers and soldiers alike took pride in wearing these new uniforms, which was a manifestation of the newly independent Filipino nation.

The Americans mockingly referred to the rayadillo as "pajamas". By 1899, the Filipinos would find themselves at war with the United States, defending their independence from an erstwhile ally.

Revolutionary and Republican Uniforms, 1898-1902

Part of the army reforms instituted by the new revolutionary government and the First Philippine Republic, was the creation of new uniforms for officers and men of the armies of the Republic. They built upon existing Spanish traditions and thus were born the Filipino rayadillo. Adapting to the times, the Filipinos also created a khaki version of the rayadillo. This was actually a global trend in various militaries at the time. The growing accuracy of rifles meant that the bright uniforms of the previous centuries were no longer suitable for combat. Bright uniforms were ideal when soldiers marched as massed infantry as an adaptation to inaccurate muskets.

Ika-anim na Bahagi: Unang Bahagi ng 1900s o Ika-20 na Siglo (1900s and 1910s)

MGA UNANG TAON SA ANINO NG AGILA

Ang ika-anim na bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila ay tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa siyudad noong 1900s, sa maagang yugto ng pananakop ng Estados Unidos. Tulad ng mga naunang "post" tungkol sa 1800s, ang panahong ito ay sagana sa mga larawan at mga likhang sining na maaaring magamit bilang reference.

Taong 1899 nang simulan ng Estados Unidos ang marahas nitong pananakop sa Pilipinas. Ang Labanan sa Maynila (1899) ang pinakamalaking enkwentro ng Digmaang Pilipino Amerikano. Ngunti pagsapit ng 1900, natulak na ng mga Norteamerikano ang mga hukbo ng republika patungo sa kabundukan.

Nagsimula na ang paghahari ng Pamahalaang Kolonyal ng Estados Unidos.

Kakikitaan ang panahong ito ng pagusbong ng samu't saring mga tipo ng kasuotan na may bakas ng mga noon ay uso na hugis at istilo sa Estados Unidos.

Women's Attire, 1900-1910s

The Serpentina Ensemble

Introduced during the early part of the 20th century, the Serpentina ensemble developed from the traje de mestiza or Maria Calara of the previous century. The panuelos were unusually big, while the sleeves are made to be huge and inflated. These sleeves are then stiffened and would feature an ingenious crease on the upper part. The panuelo matched the camisa, while a sobrefalda was worn over the skirt. The shape of the skirt was narrow on top but widened at the bottom.

Men's Attire, 1900s-1910s

The Tuxedo for Formal Occasions

The favored attire for formal occasions was the black tuxedo, with coattails or swallow tails. This coat was worn over a shirt and a vest, with a tie (black or white) worn at the collar. The coat and shirt were paired with trousers that were trimmed with satin.

For less formal occasions, various coats were worn, all European or American inspired. Hats were also an integral part of any man's attire.

Women's Attire, 1900s-1910s

Shown here are the different examples of women's wear that emerged during the transitional years between the end of Spanish rule and the start of US rule.

Featured here is the saya de cola which preceded the serpentina.

Native Women's Attire, 1900s-1910s

The style of clothing for both of these examples are versions of the early silhouette of what would later come to be known as the "balintawak". The balintawak was a country version of the traje de mestiza. The alampay in both examples is worn and used as headscarf or kerchief.

Men's Attire, 1900s-1910s

It did not take long for Filipinos to gradually acquire fashion influences from the Americans. Local suits, patterned after US styles, would come to be known as Americanas.

Also shown here is a standard outfit was worn by schoolboys, which was composed of a buttoned-up drill suit with a standing collar.

Ika-pitong Bahagi: Mga kasuotan noong dekada 20 ng ika-20 na siglo (1920s)

Ang ika-pitong bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila ay tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa siyudad noong 1920s.

Ang 1920s ay ang panahon kung kailan nagaagawan ang impluwensiyang Espanyol (na labi ng 300 taon nilang pananakop sa Pilipinas) at ang impluwensiyang Norteamerikano sa kultura at buhay ng lungsod. Makikita at madadama ang banggaang ito sa lenggwahe hanggang sa kasuotan. Ang paglago ng impluwensiyang maka-Amerikano ay dala na din ng pagusbong ng isang bagong henerasyon ng mga kabataan na lumaki sa ilalim ng gabay at pamamayani ng bandila ng Amerika.

Gayun pa man, sa panahon ding ito ay patuloy ang mga PIlipinong makabayan sa pagsulong at paghingi ng independencia para sa Pilipinas.

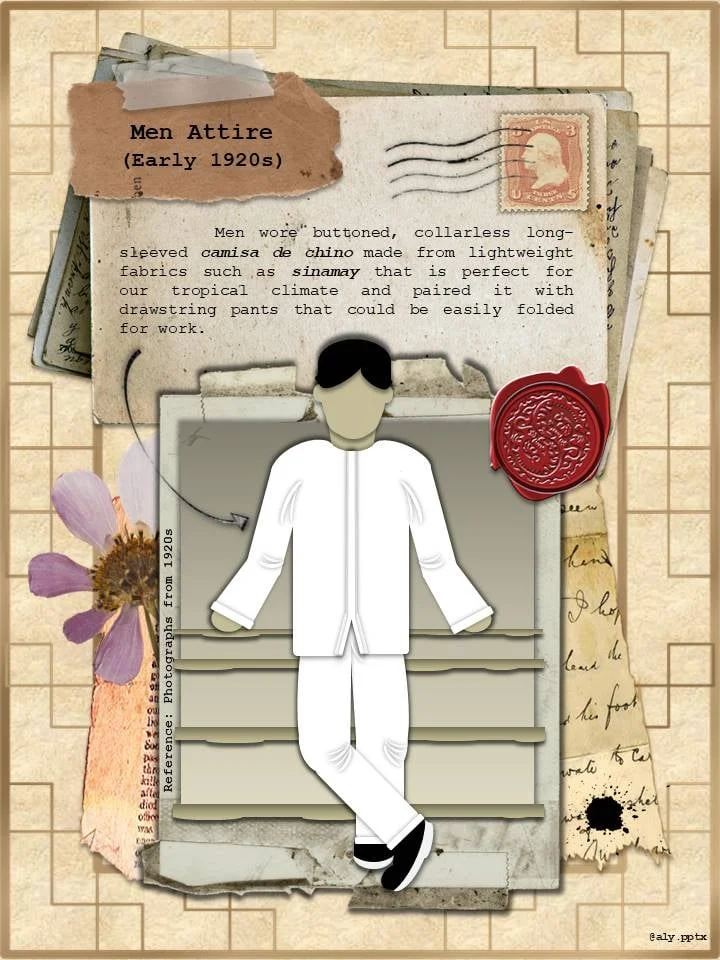

Men's Attire, 1920s

The Collarless long-sleeved camisa de chino was a carry-over from the Spanish period. It was practical to wear, worn by many working-class Filipinos. The camisa chino was made out of light fabrics such as the sinamay, making it ideal for hot weather.

Men's Attire, 1920s

The Americana

As mentioned in our previous batch of posts, the Amerikana rose in prominence during the early 20th century, although European type fashion had been preferred widely by the ilustrados as early as the second half of the 19th century. The Americana was worn by students for their uniforms.

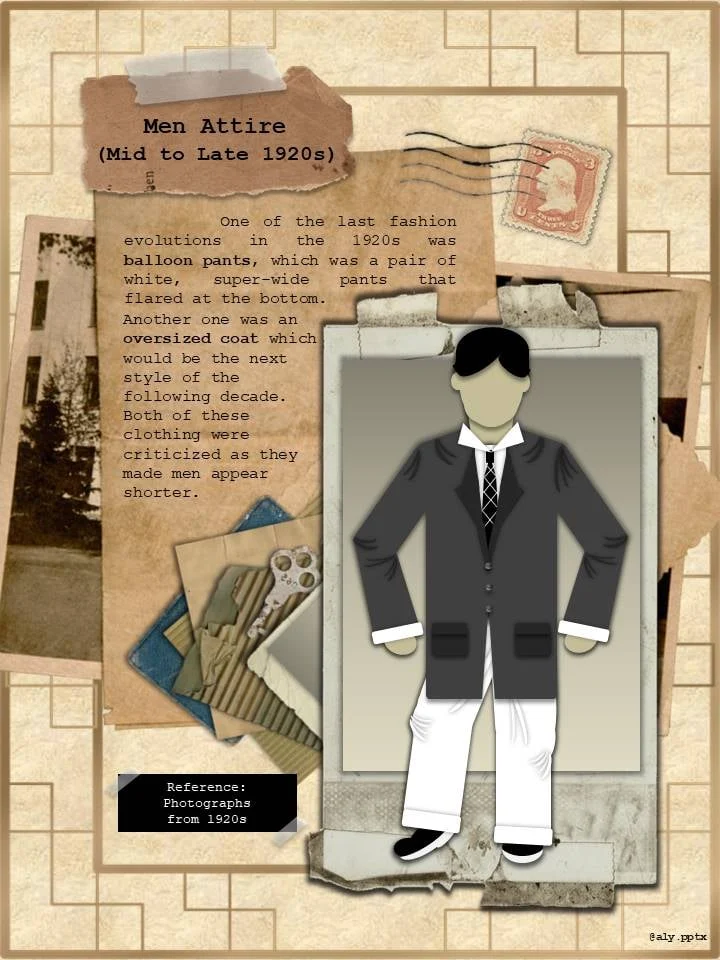

Men's Attire, mid to late 1920s

One of the last fashion trends of the late 1920s was the balloon pants, which were white, super-wide pants that flared at the bottom. Another trend was the oversized coat which would continue into the 1930s. Both were criticised as they made men appear shorter.

Men's Accessories, 1920s

Important accessories for men included a hat and a tie. Hats included the straw boater hats that had flat brooms and the fedora.

Neckties and bow ties were worn at the collar.

Women's Attire, 1920s

The Balintawak Outfit

The Balintawak outfit of the 1920s had large puffy, butterfly short sleeves. This had a plaid or decorated skirt, with plain tapis above it or it could be a plain skirt with a plaid tapis. These were worn during picnics and photo shoots.

Women's Attire, 1920s

The Balintawak Outfit

It was customary for women with means to pose for photographs wearing Balintawak outfits, while laso carrying props such as a palayok or clay pot and set in a typical country life scene.

|

| Source: ©National Museum of the Philippines |

While you may be too young to have seen your grandmother wearing garments similar to those shown in the photo below, in all likelihood, you may have seen the same in a period film, in a Filipiniana-themed event, or in a traditional dance.

In Iloko, the upper garments in the photo are generically referred to as “kimona”, while the long skirts are called “pandiling”. At least in the Ilocos, these were commonly worn by women until the 1950s. And lest you think that these were only for special occasions, we should say that there were types of blouses and skirts that women used while doing their chores at home and in the farm well until the turn of the century.

The featured garments are samples of our traditionally woven textiles and more: They are also called tropical fabrics as they are made of locally produced and processed natural fibers such as cotton and abaca. Philippine tropical fibers that can be woven into fabrics moreover include those of pineapple and banana, as well as locally produced silk. Maguey fibers and those of the known favorite Iloko vegetable “saluyot” have also been explored for their potentials as fabric material.

Recognizing the importance of reviving and promoting the use of our own tropical fibers for textile production, Presidential Proclamation No. 313 was issued ten years ago declaring the month of January as Tropical Fabrics Month. This was also to advance the interest in tropical fabrics stirred through the celebration of Tropical Fabrics Day the year before, on January 24, 2011.

Women's Attire, 1920s

The Terno

In the 1920s, a complete terno dress referred to a set of matching clothes made from the same fabric. It consisted of a camisa, panuelo, saya de cola, sobrefalda and a very visible indergarment called the corpino. An important feature of this dress was the butterfly sleeves that replaced the wide sleeves of the previous mestiza dresses. The size of the panuelo was also reduced.

Women's Attire, 1920s

Paper flowers and painted drops provided a milieu for the terno clad of ladies of the 1920s and 1930s. The saya or skirt, known as the saya de cola, had trains that came in various shapes.

Ika-walong Bahagi: Mga kasuotan noong dekada 30 ng ika-20 na siglo (1930s)

Ang ika-walong bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila ay tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa siyudad noong 1930s.

Ang 1930s ay ang dekada kung kailan nagbunga ang matagal nang paghingi ng mga Pilipino ng independencia mula sa Estados Unidos. Noong 1935 ay itinatag ang Komonwelt na Republika ng Pilipinas. Nahagi ito ng plano na sa loob ng sampung taon ay bibigyan n aang Pilipinas ng ganap na kalayaan. Subalit noong 1941, sa paglusob ng mga Hapones, sisiklab ang Digmaang Pasipiko na bahagi ng Ikalawang Digmaang Pandaigidig. Bugbog sarado lalabas ang Komonwelt na republika mula sa digmaang ito.

Men's Attire, 1930s

Double-breasted suits

The americana remained in use for many Filipinos, and one such version of it that grew in popularity was the double-breasted suit. These suits were worn with a vest underneath.

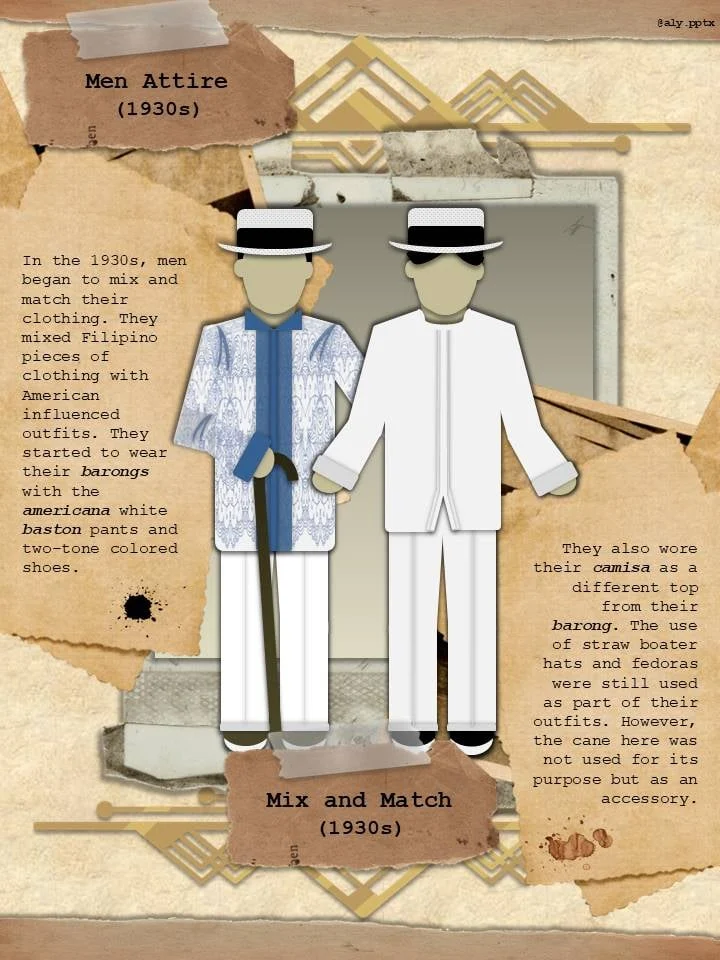

Men's Attire, 1930s

The 30's saw men mixing and matching their clothing, mixing Filipino clothing with American ones. Barongs once again emerged, mixed with the americana white baston pants, and two-toned shoes. Fedoras an boater hats remained in favor.

Men's Attire, 1930s

Featured here are other examples of how they mixed and matched their outfits.

One wears a colored camisa paired with americana baston pants, and a fedora. The other one is wearing a barong with embroidery made from delicate jusi. The barong is untucked and paired with narrow pants.

Men's Attire, 1930s

The Commonwealth Barong Tagalog

Famously worn by Manuel L. Quezon, first president of the Commonwealth Republic. It had an embroidery design featuring both the American and Filipino flags.

Womne's Attire, 1930s

Terno without Sobrefalda

Ternos continued to be in style, but the terns of the 1930s started to no longer feature the sobrefalda or tapis. In this version, the decor such as ruffles were sewn on another fabric which was then sewn on the saya.

Women's Attire, 1930s

3D Applique on Saya

Another variation of the terno. This version, however, features decorative elements that are sewn on a separate fabric that is then sewn on the saya. The decor on this saya however are embossed.

Women's Attire, 1930s

Another example of a terno without the sobrefalda. The decorative elements for this terno however was sewn directly on the saya without an extra fabric. A notable accessory in this image is the ostrich plume, which became a favorite accessory for women during studio photo shoots.

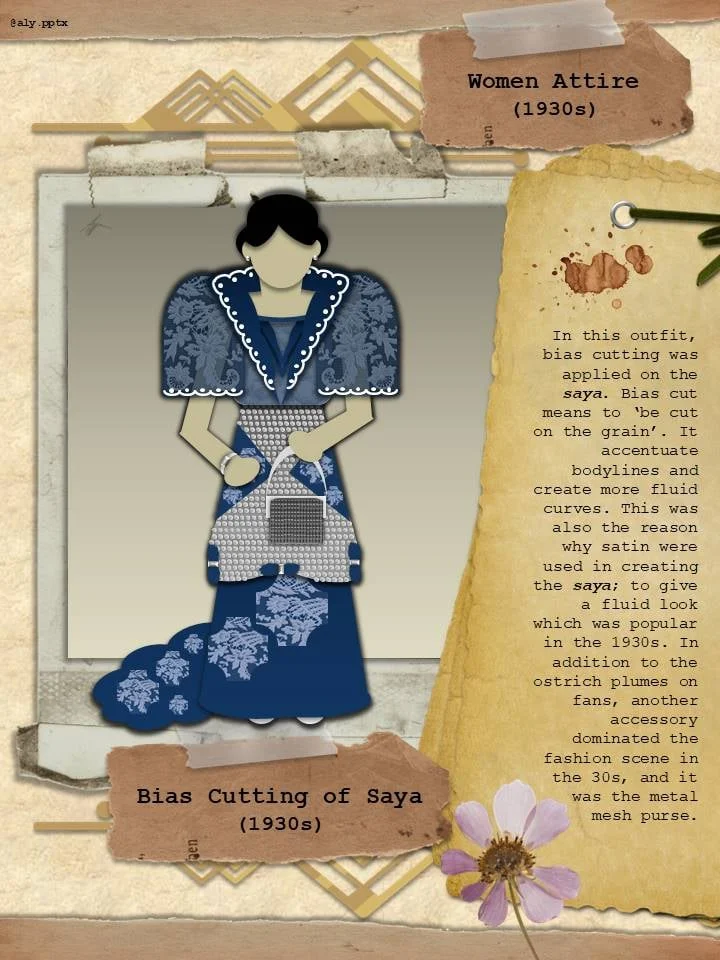

Women's Attire, 1930s

Bias Cutting of Saya

Bias cut means to be cut on the grain, which has been applied here on the saya. This was one reason why satin was used in creating the saya; to give a fluid look and accentuate body lines, which was popular in the 1930s. Another accessory that dominated the fashion scene in the 1930s was the metal mesh purse.

Ika-siyam na Bahagi: Mga kasuotan noong dekada 50 ng ika-20 na siglo (1950s)

Ang ika-siyam at huling bahagi ng serye tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa Maynila ay tungkol sa mga kasuotan sa siyudad noong 1950s.

Matapos ang Ikalawang Digmaang Pandaigidig, alinsunod na din sa mga naunang kasunduan, binigyan ng Estados Unidos ang Pilipinas ng independencia. Matapos ang halos 400 taong masasabing malaya na ang mga isla mula sa dayong pananakop.

Subalit nanatili ang matatagal nang suliranin ng bansa: kontrol ng mga dayuhan sa ekonomiya, kahirapan, kawalan ng repormang agraryo at iba pa.

Ang dekada 50 ay ang panahon ng pagaaklas ng mga Huk sa layong gawing komunista ang pamahalaan at matugunan ang daing ng maralita. Bagamat malaya na ang Pilipinas sa pangalan, di makakaila na malakas pa din ang kapit ng Estados Unidos sa ekonomiya, pulitika, kultura ng Pilipinas.

Women's Fashion, 1950s

The 1950s saw the terno disappear from everyday wear, especially for the younger population. This trend in dresses had been taking place since the late 1930s and the 1940s. By the 1950s, the silhouette of dresses emphasized a thin waistline, similar to an hourglass.

Summer and Day dresses also became popular, as well as pencil skirts and cardigans.

Women's Fashion, 1950s

Bridal Fashion

During this time, the use of the panuelo was relegated to bridal dresses. More Filipinas began to discard the panuelo from most attires starting in the late 1940s.

Women's Fashion, 1950s

Cocktail Dress Ternos

As mentioned earlier, by the 1950s, the terno had fallen out of favor among younger women as everyday wear. However, it was still worn for formal events.

The cocktail version of the terno emerged, shortly after the cocktail dress was introduced by Christian Dior. Typically mid-calf in length, it was used for afternoon and evening functions.

The terno to this day, survives more or less in teh same manner as it did in the 1950s, a dress for formal occasions.

Men's Fashion, 1950s

The Barong Tagalog, by Presidential Endorsement

Although drape-cut suits remained popular for formal wear, the use of the Barong tagalog was popularized by then President Ramon Magsaysay, leading to the rebirth of FIlipiniana fashion.

President Magsaysay chose to wear the barong tagalog in all official affairs, including his inauguration. He made it fashionable as business and formal wear.

Men's Fashion, 1950s

Men's fashion also changed during the 1950s. While americana coats were still worn for business attire, polo shirts, patterned with pants with high waistlines, became fashionable for everyday wear.

Polo shirts appeared with colorful prints. The mid-1950s also saw the heyday of the Hawaiian or aloha shirt, made attractive with printed resort motifs.

The barong Tagalog – the male national costume – and baro at saya – the female national dress

Dating back to the Spanish colonial period, piña was highly valued and collected as tribute and given as gifts to royalties. However, in the late 20th century, piña production declined due to the shortage of piña fiber. Through the combined efforts of private individuals, government agencies, and the community of farmers and weavers, it fluorished and gave way to different variants like piña combined with silk, cotton, abaca and other natural and synthetic threads.

When we celebrated the centenary of the Philippines Independence in 1998, government officials and employees were required to wear their Filipiniana attire during flag raising ceremonies in government offices held every Monday. This paved the way in revitalizing pure piña weaving in Kalibo, Aklan and in the introduction of piña-seda or the combination of piña as weft and silk as warp. The latter involved more communities from planting and growing of mulberry and Red Spanish pineapple; to the rearing of silkworms; gathering and processing of silk and pineapple fibers; weaving of piña-seda cloth; and in the embellishment of the cloth with hand and machine embroidery.

CURRENT FASHION TREND - The Evolution of the Baro at Saya

|

| Source: The House of R.T. Paras |

|

| Source: The House of R.T. Paras |

_____________________

Credits:

Illustrations/Drawings: Ang seryeng ito ay likha nina Ali at Eysee, mga kasapi ng Renacimiento Manila.

Other Photos: The National Museum of the Philippines

3 comments:

Maraming salamat dahil ito ay makakatulong para saakin

Sino po yung author hindi ko makita for citation sana

asd

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?