The Aeta People of the Philippines: Culture, Customs and Tradition [Philippine Indigenous People | Ethnic Group]

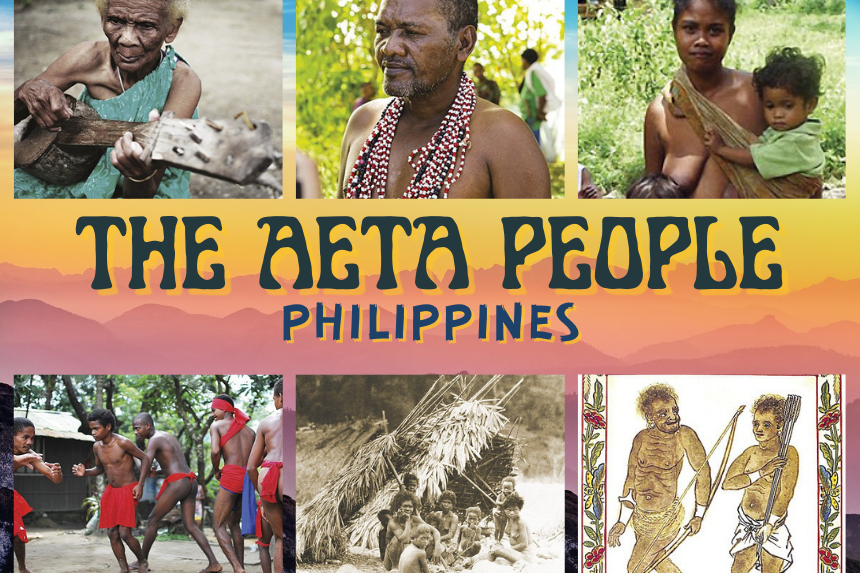

It's possible that "Aeta" is derived from the Malay term "hitam," which means "black," or from its cousin in the Philippine languages, "itom or itim," which means "people." Aeta, also known as Ayta, Alta, Atta, Ita, and Ati in early ethnographic records of the people, were sometimes referred to as "little blacks" because of their dark skin.

Short and slender, the Aeta are also dark-skinned; their typical height is 1.35 to 1.5 meters; their frame is petite; their hair is kinky; and they have large black eyes. Later migrants are thought to have driven them into the highlands and hinterlands of the Philippines, where they are thought to have been the country's earliest settlers or aborigines.

Negritos are a diverse group of people who dominate the Philippines' archipelago from north to south, despite a perceived lack of inclusive terms to describe them. Philippine Negrito groups is the best term to use when referring to the Agta and Aeto in northeastern Luzon; the Aeta, Ayto and Alta in Central Luzon; the Ati or Ata in Panay and Negros; the Batak in Palawan; and Iraya Mangyan in Mindoro. Remontado of Rizal province, the Remontado of Sibuyan Island in Romblon province, and the Ati are also included in this group.

Baluga or Ita is also known as Remontado or Ita in the provinces of Pampanga and Zambales; in Tarlac they are named Kulaman, Baluga or Sambal, while on Panay they are known by the names Ita or Ati. Aeta also goes by the names Kofun, Diango, Paranan, Assao, Ugsing, and Aita in the province of Cagayan.

It is common for non-locals to refer to the Agat and Agtan people of the Philippines as "Dumagat" (meaning "seafaring people"). They are known as Mamanwa in Mindanao's northern provinces of Surigao and Agusan. the words man (first) and banwa (forest) combine to form mamanua, which means "forest inhabitants" (forest). However, the Mamanwa have also been referred to as "Kongking," which translates to "conquered" in Spanish.

As a result of their diverse social and geographical contexts, the Aeta have a wide variety of distinct names to call themselves. Aeta groupings have been classified in a variety of strange ways. Non-Aeta groups or neighbors may take offense to a name given by an Aeta group, especially if the given name is considered derogatory.

The term "Ita" is offensive to certain Filipinos because of their dark skin tone. The Aeta are sometimes referred to as Baluga, which translates as "hybrid," in Central Luzon. As "brackish, half-salt, half-fresh" implies, other Aeta groups find this disrespectful. One subgroup of the Aeta of northern Luzon is known as the Ebuked, which comes from the Filipino term bukid (field) and refers to people who dwell distant from the lowlands. They are collectively known as the Aeta or the Agta. The Agta view the Ebuked as primitive and backward. In the north of Luzon, another ethnic group is known as the Pugut, a term used by their Ilocano neighbors to describe people with dark skin. Goblin or forest spirit are other possible translations in Ilocano.

"Abiyan" means "companion" or "fellow" in local dialect for the Aeta of Camarines Norte and Camarines Sur. During the Spanish period, this particular group worked for wealthy Christian landowners, hence the name. The term "Bihug" comes from the Abiyan slang term "kabihug," meaning "fellow at the meal." Workers in Quezon province known as Aeta, who clean coconut plantations and do odd labor for food and cloth, are also called Abiyan. Ata, Atid, and Itim are some of the other names Quezoners use to refer to themselves.

The Aeta population is made up of approximately 30 distinct ethnic groups. There are 117,782 Aeta people in the Philippines or one percent of the country's overall indigenous population. As of 2010, the Agta of Northeastern Luzon had 10,503; the Pinatubo Aeta had 56,265 members in 1997; the Mamanwa had 54,394 members; and the Ati had 9,258, distributed throughout the Visayas, with the majority living on Iloilo and Capiz islands.

It is interesting to note that despite significant social, political, economic, and geological changes, as well as distressing environmental shifts over the last two centuries, the distribution of the Philippine Negrito groups has stayed mostly unchanged. Despite this, they can still be found in parts of Western Cagayan, the Sierra Madres, Central Luzon, the Island Group, and Mindanao.

The Aeta group's diversity is evidenced by the fact that over 30 different Negrito languages have been recorded. However, only 17 of these are currently being used—namely, Abelling, Abiyan, Aeta or Ayta, Aggay, Agta, Atta (aka Ata or Ati), Batak (aka Binatak), Cimaron, Dumagat (aka Umiray), Iraya, Isarog, Kabihug, Mamanwa, Manobo or Ata-Manobo, Negrito, Remontado, and Tabangnon. In order to communicate with the locals, many Aeta have learned the language of the lowlanders they've encountered.

History of the Aeta tribe in the Philippines

It is still a mystery as to the origins of the Aeta, which anthropologists and archaeologists continue to investigate. 30,000 years ago, the Philippines was connected to Asia by land bridges, which brought the initial inhabitants of the country to the Philippines. The Malay peninsula was once connected to Sumatra and the remainder of the Sunda Islands, which could explain these migrations. It's possible that the Aeta dispersed throughout the archipelago that is now the Philippines at the time of their arrival.

|

| Depiction of the Negritos, circa 1590 (Boxer Codex, The Lilly Library Digital Collections) |

The Aeta are more closely related to Asia-Pacific tribes than to the African group, according to genetic research. There is speculation that the Mamanwa have some unique genetic material not seen in the other Aeta tribes. These people are related to the indigenous peoples of Australia and New Guinea, who are descendants of Africans who migrated south. As an Australoid people, the Aeta are defined as having "enhanced survival value in a hilly tropical climate with inadequate nutritional resources." About 45,000 years ago, the first Australian aborigines arrived on the continent. The Mamanwa are thought to have broken apart from their common ancestor 36,000 years ago. As a result, the Mamanwa people may be the country's oldest ethnic group.

According to Chau Ju-1225 Kua's chronicle, the Aeta were known as the Hai-tan. When thrown a porcelain bowl, they'll leap to their feet and roar in delight, according to reports of these masked assailants perched on tree limbs and ready to take down unsuspecting onlookers. On one of these islands "in some of these mountain regions are blacks inhabited by Indians as a general rule, and whom the latter capture and sell, and even employ as slaves," according to Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, a 16th-century explorer. Blumentritt was one of several writers who adopted Colin's theory about the Philippines' first residents being black mountaineers in the 18th and 19th centuries.

|

| Aeta family in their traditional lean-to house, 20th century (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

There are archaeological pieces of evidence indicating that, prior to the Spanish conquest, Aeta peoples lived in the lowlands, but they gradually relocated to the hills and highlands as a result of succeeding immigrants and conquerors like the Spaniards. There is evidence that the Zambales Aeta, for example, lived in the lowlands and along the coasts and rivers of the Zambales River.

The Aeta are known for their resistance to change. Throughout the span of the Spanish administration, the Spaniards' attempts to relocate them to reservations failed. Only when lowlanders established artificial government structures, such as a consejal (city councilor), a capitan (barangay commander), or police, did the political organization of the Aeta change.

With the acquisition of new colonies, particularly the Philippines, in the first decade of the 20th century, the United States became a global force. It was in Missouri, in order to present itself as a global superpower, that the United States created the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. At the time, the world fair was the most ambitious effort of its type ever undertaken. The 47-acre Filipino reservation, which included 100 buildings, cost two million dollars. There were 1,100 individuals from the Philippines living on the reservation. Negritos and Mangyans made up 38 of the ethnic delegates. In the Philippines, the Negritos were supposed to represent those who were the least civilized.

Only the Pinatubo Aeta, who lived around the former US military bases in Zambales and Pampanga, were willing to engage in communication with the visitors from the United States. General Douglas MacArthur commended them after the war for their assistance to the US Air Force soldiers. They were permitted to penetrate the perimeter of the base and participate in scavenging activities there. The American special operations forces used them as jungle survival teachers as well.

Video: Paano nakaligtas ang mga katutubong Aeta sa pagsabog ng Mt. Pinatubo?

Mount Pinatubo erupted in 1991, forcing the United States to leave the bases. For more than a decade, the Aeta ancestral lands were buried under ashfall and lahar from this volcanic eruption, one of the largest natural disasters of the twentieth century. More than 50,000 people were killed by an earthquake that struck the Pinatubo Aeta on August 12, 1980.

The Aeta people of northeastern Luzon rebuffed attempts in the 1930s to introduce farming to their culture and were driven out of the area. They were able to adapt to social, economic, cultural and political challenges with amazing resilience, developing systems and structures within their society to lessen the impact of change when necessary. The Aeta, on the other hand, have declined in numbers during the second half of the twentieth century. Environmental catastrophes and anti-people sociopolitical and economic policies have put their very existence in jeopardy for decades.

Colonial and economic policies in the United States prior to World War II emphasized large-scale commercial logging and mining of the country's natural resources. Extractive industries continued even after the Philippines gained independence from the United States. Mining claims made by large corporations proliferated under the Marcos administration, which was bolstered by a presidential decree in favor of mining. Deforestation accelerated as foreign businesses and Marcos loyalists were handed wood licenses. Even after the EDSA Revolt in 1986, the administrations continued to encourage logging and mining activities.

Nickel mine operations prompted the Mamanwa to relocate to the lowlands in 1986. Mining deposits abound throughout the majority of Mamanwa traditional territories. Among the greatest iron deposits in Asia is Claver in Surigao del Norte, for example. Displaced from the trees that sustained their traditional lifestyle, the Mamanwa struggled in their new locations. Furthermore, the mining operations harmed the natural environment by clogging the waterways. Reversal of the Mamanwa's peaceful way of life was brought about by mining firms entering the Surigao provinces in the 1970s and 1980s.

Illegal and legal logging on the eastern side of the Sierra Madre mountain range has decimated Agta hunting and gathering practices. Because of the loss of forests, Aeta had no access to the plants and animals it needed to thrive. Hundreds of Agta were killed in Quezon province as a result of flash floods and mudslides caused by tropical depressions and typhoons in November and December of 2004.

With the support of social-forestry initiatives like Integrated Forest Management Agreements and Community-Based Forest Management Agreements, the government has attempted to address the issue of deforestation in the country (CBFMA). Nagpana, a forest reserve on Panay Island, was designated as an Ati-only area in 1986. The Department of Environment and Natural Resources is in charge of it (DENR). According to the agreement, the Ati are allowed to live in the forest, but they are prohibited from using forest resources for charcoal production or using forest land for kaingin (swidden farming). That's why they've started selling herbal treatments in nearby island provinces like Samar and Leyte and Cebu and Negros in order to make ends meet. As a result, Ati communities have sprouted up in places like Naga, Cebu, and Janiuay, Iloilo.

In 1998, the Batak of Kalakuasan in Palawan signed a CBFMA with the DENR covering 3,458.70 hectares of forest in Barangay Tanabag. It's a deal that Batak see as unsatisfactory because it only lasts 25 years and is only renewable if Batak can meet unattainable standards. Furthermore, the Batak are unsatisfied with their position as DENR subsidiaries because of the CBFMA's lack of security of tenure.

In addition to deforestation, the Aeta has been troubled by expulsion, displacement, serfdom, and mendicancy. Since the government and insurgent New People's Army (NPA) have been engaged in a long-term military war in rural regions, the Philippine Negritos, whose forest habitats are also battlegrounds, have been harmed. 400 Mamanwa households in Taganito, Surigao del Norte were evicted from their ancestral lands in the 1980s by military authorities who accused the Mamanwa of supporting the NPA. Families are being forced to flee their homes as a result of the harassment and expulsion they have been subjected to.

Aeta peoples have also been displaced from their natural grounds by hungry lowlanders in search of food. The Madia-as mountain range, which separates Iloilo and Antique, was the ancestral home of the Panay Ati. When the forest was reduced in the 1950s, the locals turned to swidden farming, selling medicinal herbs for a profit and working as farm laborers. Some Visayans took advantage of the time between planting seasons when Ati ancestral grounds were lying fallow and applied for government land titles for these ancestral holdings. The Ati attempted to retake their ancestral lands, but they were unable to demonstrate legal possession because they did not have the proper documentation.

The Ati in Negros have been reduced to the status of agricultural laborers or tenants, forced to work on land that was once theirs. In the lowlands, people hire them to do things like plow fields, collect coconuts, and cut bamboo into fish traps. A large number of Christian families employ women as maids or farm workers. A few people in Iloilo have taken to begging on the street. So it comes as no surprise that some Aeta (especially the Dumagat) succumb to alcohol. In the Dumagat culture, alcoholism was originally unknown. Lowlanders likely introduced it and unscrupulous merchants reinforced it by providing alcoholic beverages as payment for Aeta work. Even among women, intoxication has become a societal issue.

A Certificate of Ancestral Domain Title issued under the provisions of the Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997 (IPRA) gives Aeta tribes official acknowledgment of their ancient territories and waters (CADT). It has been possible for certain of the Pinatubo Aeta, Agta/Dumagat, Ati, and Mamanwa tribes to get land titles over ancient lands after enduring a time-consuming bureaucratic process. 400 Mamanwa families, for example, purchased a CADT in 2006 covering 48,870 hectares in Surigao del Norte, including a section of Agusan del Norte.

A formal land claim does not guarantee that indigenous peoples will be freed from their plights. This new income, which amounts to millions of pesos, has sparked friction among Mamanwa chiefs, who have been empowered by the IPRA to negotiate for a one percent royalty of the gross production of mining firms operating in their territories. Even though Quezon province's Agta/Dumagat ancestral lands comprise 164,000 hectares, they have not been safeguarded against illegal logging and the construction of a hydro dam that will eventually bury their forests and sacred sites.

Modern leaders have championed the group's economic, political, and cultural rights in recent times. At the vanguard of the Laiban Dam protests in 2009 was Napoleon Buendicho, a prominent Agta/Dumagat leader in Quezon. Tribal Council Governor Buendicho of the Agta/Dumagat and Remontado of Quezon Province led his fellow Agta in protesting the development of a dam that will flood at least nine barangays in Tanay, Rizal, and General Nakar, Quezon and leave 5,000 Agta homeless. Thirty Ati families headed by Dexter Condez obtained their CADT in 2013 on Boracay, a popular tourist destination. The CADT is located in Boracay's Barangay Manoc-Manoc and covers 2.1 hectares. However, private investors and other land claimants have disproved their claims. In February 2013, Condez was slain, and the Ati ancestral property's outer fences were destroyed. In order to protect Ati and local officials who were implementing CADT, the national government had to designate police authorities. Ati and island civilian authorities continue to face dire threats in spite of the National Commission for Indigenous Peoples' issuance of a warrant of execution confirming their land claim.

Pinatubo Aeta

|

| Group of Aeta in Zambales, early 20th century (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The Pinatubo Aeta are members of a group of indigenous groups that inhabit hilly and forested places around the island. They're thought to be descended from the people who lived in the Philippines before the Spanish arrived. They are considered a significant ethnic group by social scientists. In addition to being the largest in number, they have maintained their cultural identity through the ages. 83,234 people were estimated to be members of the Aeta groupings in 1988. Pinatubo was home to the lion's share of this population. The Pinatubo Aeta grew at the same time as the Aeta in other parts of the country declined, a phenomena ascribed to Mount Pinatubo.

Prior to the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo, the Aeta occupied Zambales towns of Botolan, San Felipe, Cabangan, and San Marcelino; Mabalacat, Porac, Angeles, Floridablanca; Capas, O'Donnell, Bamban; and Dinalupihan in Bataan. Aeta is surrounded by the Tagalog, Kapampangan, Ilocano, and Sambal peoples of the lowlands, all of whom speak their own dialects of Tagalog.

Mount Pinatubo, which stood at 1,745 meters above sea level before the explosion of the volcano in 1991, was home to a wide variety of plants, wild fruits, and medicinal herbs. The landscape was also densely forested, with a wide range of tree species. It seemed as if rattan was everywhere. During the day, the air was muggy, but as the sun set, the temperature began to drop. Its terrain was difficult and inaccessible to land vehicles because of its variable topography, rough interior, and rugged interior regions. Trails and streams wound their way through the slopes, connecting several settlements. The hilly region is home to a single river that flows into the West Philippine Sea. During the rainy season, its tributaries cause a lot of erosion in the surrounding villages.

Its lower and higher reaches were home to a variety of barrios and sitios. People living in the mountain's lower grasslands and secondary forests are classified as "acculturated" or "isolated," depending on where they live in the mountain. There were only a few acculturated villages in the Pinatubo region by 1976: Yamot, Mantabag, Kalawangan and Taraw were the only ones left, with Maguisguis, Villar and Poonbato the only others. The Pinatubo Aeta were vulnerable because they were ill-equipped to deal with external pressures after being driven from their ancestral territory. As was to be expected, they were among the most severely affected by the largest volcanic eruption of the twentieth century.. Aeta of Zambales lived in 24 villages before disaster: Tarao or Makinang, Manggel and Kalawangan of Zambales; Belbel and Balinkiang of Lukban and Belbel of Belbel of Balinkiang of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of Yamot of As a result of the blast, all of these were left in the dust. Lahar covered lowland areas around the volcano as it erupted, forcing evacuations and stopovers in various evacuation camps for evacuees.

But their incredible resiliency was demonstrated by the fact that their population remained roughly steady even despite decades of displacement. There were 56,265 Aeta in Zambales province in 1997, according to data from the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP). This is close to the population level prior to the 1991 calamity.

The Pinatubo Aeta have also lost their original language, like other Aeta tribes. Those who live on the coastal plains near Mount Pinatubo can now communicate in the Sambal language, which is spoken by lowland people. Those Aeta who live in Pampanga speak Pampango, whereas those who live in Bataan speak Tagalog on Mount Pinatubo's Batan side speak Tagalog. However, the Aeta people of Pampanga and Tarlac still speak a language known as Ayta Mag-anchi. There were some communities in Pampanga that spoke it before Mount Pinatubo's erupting ash cloud engulfed the region. Many barangay residents in Capas, Tarlac, spoke Ayta Mag-anchi as well. Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, and San Clemente were the places where native speakers of the language could be found after the volcanic eruption.

Way of Life of the Aeta

The indigenous Aeta economy has traditionally included hunting and gathering food. The Aeta, except for those in Tarlac who knew how to produce rice, were nomadic hunters and fisherman in the 1880s. Fishermen used bows and arrows and dogs to harvest fish, and domesticated dogs to hunt for food like snakes and frogs. Wild fruits, vegetables, and honey were collected by women.

Chinese and Christian Filipinos exchanged beeswax and arrowheads for tobacco and betel. It was common for the Aeta to employ three types of arrows for different types of games. This quiver was made of bamboo and contained arrows tipped with poison made from roots and herbs. They like to hunt at night using a flashlight that is attached to their hands with thick rubber bands during the dry season. The animal's eyes are clearly visible in the beam of light. After then, the light is dimmed to make it easier to creep up on the prey. A second time, the arrow is elevated and pointed directly at the animal.

|

| Group of Aeta deer and hog hunters, 20th century (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

A wide range of traps and hunting methods are employed by the Mamanwa. During the rainy season, from November to April, hunting is at its peak. To catch deer, pigs, monkeys, iguanas, and other large animals, the Mamanwa used bayatik (spear traps) and gahong (pit traps) in the forest.

|

| Group of Aeta rowing their banca on a river, early 20th century (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

We've seen a wide variety of fishing methods in action. Both freshwater and ocean fishing are practiced by the Aeta of Antique in Panay. Everyone in the neighborhood uses their bare hands to catch gobies, shrimps, and crabs. Building watertight dams with the help of parents, children redirect the flow of an adjacent river toward the main body of water. Fish, eels, and shellfish are harvested from the riverbed by hand once the water has receded. Aeta Pinatubo uses more modern methods. They use a metal rod attached to a rubber band to catch fish as they swim. The Ati of northern Negros has been spotted using hazardous fishing methods, hurling explosive lime bottles into the water.

Several Aeta tribes rely on honey-gathering as a major source of income. Pinatubo Aeta and Ebuked Agta eat honey as a delicacy. Besides nectar and honey, the Pinatubo Aeta also devours immature bees and pollen from hives. Prior to 2010, the Aeta Magbukun of Mariveles, Bataan were heavily involved in the honey-harvesting practice known as "pamumuay." It takes Aeta dads or elder brothers a week on a luwak (backpack) to go to the forest and get honey. In the height of pamumuay season, boys skip school to join their mothers in harvesting big trees. Traditionally, honey is packaged and sold by women in repurposed whiskey bottles. Around 3.4 to 7 liters of honey per week can be harvested by an average Aeta Magbukun household during tag-pulot (honey season), which starts in mid-December and lasts until May. It's a good time to be them during Tag-pulot, because they can afford to pay their bills with their weekly income of roughly 3,000 pesos.

Rattan gathering is a key source of income for the Dumagat and is mostly carried out by men. They don't have a set work schedule and meet every day. Rattan stems are gathered from the forest, cleaned and scraped, and then split into long, narrow pieces as part of the work cycle. Rattan is delivered by the hundreds by the Dumagat to the merchants. The Dumagat receives a basket of products containing sugar, rice, salt, soap, and betel nut from these merchants, who reside in the lower regions. The Dumagat have no idea how much their job is worth in terms of money. Their incomes are frequently insufficient to cover their basic needs. Since the Dumagat cannot pay the hefty interest rates, they are compelled to take on debt from merchants. Due to the merchants' constant need to collect more rattan as payment, the vicious debt repayment cycle never stops.

The Agta are commonly described as commercial hunters and gatherers. Instead of hunting and gathering as a means of subsistence, those who engage in commercial gathering do it as a means of bartering their labor for carbohydrate-rich foods. It's likely that Kaingin is a very new addition to their way of life. As recently as 1975, for example, the Casiguran Agta were spotted engaging in the practice.

The Ati of the Visayas, who lived in permanent farming towns in the early 1960s, practiced agriculture. For food, the Ati settled in these areas and grew a variety of crops such as corn, wet and dry rice and abaca as well as sweet potato and cassava.

Systematic food production is new in the Ati case study. Although the Aeta have a subsistence economy, they are being drawn into the cash economy of most Filipinos. Hunting and gathering may give way to agriculture because forest grounds are disappearing rapidly, lowlanders are moving into the ancestral domain of Aeta, and cash crops offer an attractive alternative source of income. Agricultural dependency increases as the Aeta become more involved in a monetary economy. To make a profit, the Batak of Palawan, for example, collect rattan cane, wild honey, and bagtik, a resin made from Agathis philippinensis, among other things.

Historically, bagtik or almaciga are used as house torches in the Philippines. To create varnish and paints of the highest quality, linoleum adhesive, waterproofing compounds, and adhesives, tapping resin became a need after World War II. For centuries, the Batak have been masters of resin gathering, utilizing a process that does not harm trees, unlike the destructive methods used by lowlanders.

Aeta can earn money in other ways as well, of course. In weaving and plaiting, the Aeta have a talent. Handicrafts are made to meet the everyday necessities of the community, as well as for personal decoration and exchange with outsiders. Winnowing baskets, armlets, small bags, and mats are all products made by the Mamanwa and Agta tribes. Bartering and trading honey and tamed animals, as well as selling medicinal plants and roots, are common pastimes among the Ati of the Visayas. The Pinatubo Aeta are known for their mastery of metalwork, making it their most highly skilled vocation. A majority of the work is done by males, but women and children may also participate in the process.

The Aeta are still getting to grips with the idea of land ownership and formal titles. With the support of lowland allies in government offices, certain communities like the Mamanwa of Agusan have been able to gain land titles. However, the land is usually sold soon afterward. Due to the fact that traditional Aeta tend to be short-term foragers, this is the case. They've been conned into selling their titles for food, clothes, and trinkets, or putting them up as collateral for debts.

It is possible for the Aeta to be empowered by legislation such as the 1997 IPRA and Executive Order 247, which safeguard indigenous peoples' rights. Using natural resources and genetic materials in ancestral domains with legal titles in the Philippines ensures that monetary and non-monetary profits are shared, according to Philippine law. It is common for laws to govern and prescribe profit-sharing for the scientific and commercial usage of plants and animals. In exchange for allowing mining corporations to operate in their ancestral territory, the Mamanwa are entitled to take a one-percent portion of the gross revenues. The Pinatubo Aeta also want a piece of the money generated by visitors to the area around Mount Pinatubo. Subic Freeport and the Aeta of Zambales and Bataan agree on financial and non-monetary benefits from the utilization of their ancestral lands.' Negotiations might take a long time, but the payoff is worth the effort. Civil society and government organizations help Aeta groups negotiate with businesspeople, especially large corporations and international investors, because the Aeta groups need unique assistance in negotiating with businessmen.

Indigenous Aeta's Self-Identity, Sociopolitical Structures, Political System and Self-Determination at the Local Level in the Philippines

The Aeta's political system is mostly built on respect for elders who are in charge of judicial matters and are responsible for maintaining the band's peace and order. Aeta characteristics like honesty, openness and a lack of interest in gaining authority and influence for one's own benefit have resulted in an informal system.

We can think of it as an open-minded democratic political group. The main responsibility of the chieftains, who are often elders, is to keep the band in good order. Tradition serves as the foundation for the generally recognized rules and regulations. It is up to the pisen (elders) of Palanan, Isabela, to decide on critical communal issues. Panunpanun is the Ati term for this group in southern Negros. The panunpanun's leader is the group's eldest member. He or she must also be a good advisor, a good arbiter, and a mananambal (eloquent speaker).

|

| An Aeta chieftain, center with top hat, and his community in Bataan, early 20th century (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

However, it is still up to each individual to accept the judgments of the elders or chiefs. Members of the Agta band in northern Luzon are never forced to follow the advice of their leaders. They persuade through examples of good deeds.

They have also disrupted the tribal political structure by forcing them to elect members of the Aeta who serve in quasi-legal posts like councilors, barangay captains, and paramilitary officials who serve as a conduit to the outside world and not necessarily as leaders of the tribes themselves. Civic and religious groups in the lower regions have assisted some Aeta groupings in consolidating and pursuing their rights.

Native American rights are protected by the 1997 IPRA, a landmark law that was passed in 1997. As a result of the law, traditional Aeta leadership and sectoral organizations are being revitalized and strengthened. Their elders can accept or deny projects or activities inside their ancestral lands, as CADT holders, because they have the authority as CADT holders. Pastolan Aeta, for example, covers 4,200 hectares, some of which are located in the Subic Bay Freeport area. It is the Aeta's right to implement the IPRA law, which ensures them control over the Subic Base Management Authority (SBMA), the area manager, through their elders council.

Aeta Tribe Social Organization, Customs, and Tradition

With an average size of 10 families or 50 people descended from a common ancestor, the Aeta live in tiny groups. A lack of social stratification or classes is also evident.

In Aeta society, the nuclear family is the main social unit, however widows and widowers receive special attention. They appear to have equal rights and responsibilities as a couple, and their relationship appears to be pleasant. Parents and children have a solid relationship, and children are valued. As a result of this, the children show respect for their older relatives—their parents, aunts, and uncles.

|

| Batak mother and her two children, 2014 (Henson Wongaiham) |

Lowland culture has influenced traditional marriage traditions. Elders used to have a strong influence over how people got married in the past. When they were first introduced, they could only be organized by the couples themselves.

The Aeta mostly practice monogamy, although some communities allow polygamy. Among the Agta, it is customary to marry someone from a different ethnic group, a practice that may be widespread. The act of incest is frowned upon. First cousin marriages are common among the Pinatubo Aeta, but only after a rite known as "separating the blood."

The Dumagat have a tradition of courtship. Dropping ilador tibig leaves along the path where she gathers water is a way for a boy to show his feelings for her. The places where the bamboo leaves were dropped indicate whether or not she likes him. If she doesn't, she'll cover the ilador tibig with other leaves. Afterward, the boy would sing for her at her house. A gift in cash or in kind, such as a bolo or dress, must be given to the girl's parents if she is the youngest of her sisters.

By the time a young man reaches the age of 20 and a young woman reaches the age of 16, they can get married. All grooms must pay a bride-price in the form of a "arrow-bow bolo," "cloth," or "homemade firearm" in addition to money. By donating a piece of their bandi to the girl's family, the boy's family arranges for him to marry her. Alternatively, the male could be compensated by providing services to the girl's family. After the couple's marriage, the boy or his family may pay the further installments. When the wife's family fails to pay the bandi, it might cause strife among the Pinatubo Aeta. Elopement with someone who was not previously contracted is another source of the difficulty.

|

| Aeta wedding ceremony, 1904 (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Every Aeta chapter has its own unique wedding ritual. When it comes to Dumagat weddings, the Dumagat sakad (a series of around three official meetings between the two groups) takes precedence over the kasal (wedding eating and drinking). It is customary in the Abiyan culture for the boy and girl to smoke a cigarette made of grass, which is then lit and given to them by their family members. Abiyan wedding traditions include the preparation of a betel combination for the couple to suck on.

The bride-to-be lives in the home of her husband-to-be. However, further studies demonstrate a shift in people's preferences for where they live. Whether or not the chosen location is close to one's parents, newlyweds prefer to reside in areas with agricultural land.

If both parties agree, divorce is possible. Laziness, cruelty, and unfaithfulness are all acceptable reasons for divorcing your spouse. In the end, the decision is made by a joint council of both families. The children are taken away from the guilty party. If the lady is to blame, the bandi must be returned to her. After a divorce, both parties are free to remarry.

The Aeta tribes consider intermarriages with lowlanders to be acceptable because of the social standing that may be achieved through such unions. Physical differences between the Aeta and lowlanders are thought to be reduced by these measures. Nearly all lowland men married Aeta women in Negros Island by 1974, but the Batak rarely married someone from Tagbanwa.

A pregnant woman's safety is guaranteed in their community. The safety of an unborn child necessitates restrictions on pregnant women. She should avoid tying knots or treading on cordage during childbirth, according to the Pinatubo Aeta. She must not be there when the stored tubers are dug out in order to avoid an early birth. Twin bananas and other oddly shaped fruits should not be eaten by her since they could cause a freak to develop in her.

Aeta women typically have an easy time giving birth and can return to work within a few hours of the delivery. A worldwide practice, massage, has been around for a long time. When it comes to childbirth, Aeta women of northern and eastern Luzon prefer to sit or kneel, unless there are significant complications and lying down is preferable. The birth of a child is open to all who wish to be present. A bamboo blade with a fine point is used to sever the umbilical chord. A loincloth is used to wipe the newborn after it has been wrapped in a little piece of cloth, laid by the mother's side, and smeared with ashes. That's because fire and ashes, which the Aeta believe protect them against evil, illness, and the cold.

Postnatal practices handle the umbilical cord and placenta symbolically. In the event that the infant becomes ill, the umbilical cord can be rendered inert and administered as medicine. Even in the privacy of your own home, it can be displayed in the form of an ornament. Hanging it dry and throwing it in the water can also help the child's development. The placenta can be disposed of in a variety of ways, including burying it under the house or returning it to the location of birth. The placenta is thought to cause illness or death if it is not properly disposed of.

Male circumcision is practiced by the Aeta, in which the foreskin is sliced open rather than cut off. Circumcision in the Dumagat language is referred to as bugit. An indication that a boy's role as a husband-to-be is about to change, young men between the ages of 11 and 16 are circumcised. The Agta of northeastern Luzon believe that a boy becomes a man when he or she kills or captures a wild animal on his or her own. The boy's father now considers him a man and allows him to date a girl from another tribe.

The commencement of menstruation marks the beginning of a girl's adolescence. In other words, when she has her first period, it's time to start dating, get engaged, and get married. It's customary for mothers to give their daughters crimson headbands when they've had their first menstruation as a mark of respect.

Even though the Aeta groups differ in their funeral customs, the following characteristics are found in all of them: Mourners leave material artifacts beside the cemetery to ensure the deceased's continued goodwill, and the burial site is abandoned after the grieving period.

Religious Beliefs and Practices of Ethnic Filipino Aetas

|

| Mamanwa leader blessing the offerings at the inauguration of the Mamanwa Cultural Center (Photo by Jimmy A. Domingo in De la Torre 2005) |

Aeta's Way of Living: Dwellings and Community Settlements

Aeta Arts and Crafts

|

| Mamanwa man carrying tampiki or rattan basket in Kitcharao, Agusan del Norte (Photo by Jimmy A. Domingo in De la Torre 2005) |

Cultural and Oral Literature of the Aeta People

MuminuddukamA ningngijjitam. (Pinnia)(It wears a crown but isn’t a queenIt has scales but isn’t a fish. [Pineapple])Assini nga pinasco ni ApuNga magismagel yu ulu na? (Simu)(There is a cave with a bolo in itFull of bones it isn’t a grave. [Mouth])Ajjar tangapakking nga niukAwayya ipagalliuk. (Danum)(When you cut itIt is mended without a scar. [Water])

Aeta Mythology: The Legend of Creation

There was no earth in the beginning, according to an Aeta creation narrative that is also known to the Mangyan. Manaul, a winged king who had been imprisoned by his vengeful opponent Tubluck Lawi, managed to escape.For not being able to locate somewhere to sleep, King Manaul vented his fury at both the sky (with fierce winds) and the ocean, which responded by unleashing tremendous waves.Manaul, on the other hand, was nimble and light on his feet. The battle carried on for years before both parties grew tired and agreed to compromise. Then Manaul requested for light, and he received thousands of fireflies in response.All kinds of birds were provided to him as counselors when he requested for them. In contrast, Manaul pounced on the chicks and small birds with equal ferocity.The fireflies were devoured by the owls and other huge birds, who in turn fed on them. Angry at the owls' disrespect, Manaul replaced their eyes with larger ones and ordered the birds to stay awake all night as a form of punishment.Angrily stamping his feet and spitting out lightning, thunderbolts, and winds, the king of the air lashed out at Manaul for what he had done to his advisers.Also, King Captan of the Higuecinas, a genius among seafaring people, attempted to smash Manaul by throwing massive rocks and stones from the skies. Because he kept missing, land began to form.

Musical Instruments of the Aetas

Aeta's Traditional Songs

Umanga kitam didiya takawakanamNge kitam manggeyok ta agetTa isulit tam tatahiman tamTa wan kitam nga makaddimas nga Agta.(Brother come,Let’s hunt wild pig,To barter for something good,So that we will not be hungry.)

What is the song called "Kakanap?" It is sung by two Agta. In the kakanap, each melodic phrase is six syllables long. The sentences are sung one after the other, except for the final phrase, which is performed jointly. A Christian kakanap is as follows:

Eeyoy, eeyoy

Anu oy, anu oy

Itta ay kofun ko

Had en o, had en o

Awem ay maita

Atsi o, atsi o

Te itta in teyak

Had en o, had en o

Apagam, apagam

On man tu, on man tu

Ayagam, ayagam

On mina, on mina

Petta kofun hapa

Anu kan ngagan na

Hesus kan Hesus kan

Onay o, onay o

Kofun tam hapala

Onay o, onay o.

(My friend, my friend,

What? What?

I have a new friend

Where? Where?

This one you can’t see.

Why? Why?

He is with me here.

Where? Where?

Try to look for him

Where then? Where then?

Now you call him.

I wish I could.

So you can be friends too.

What’s his name?

Jesus is his name

Is it? Is it?

Jesus is our friend.

O yes! O yes!)

The magwitwit is an Agta fishing song sung solo in metrical rhythm

Angay nge takaalapan nga magwitwit tahayawTahikaw posohang kunga magwitwit tayawTatoy dimumemat ngaibayku magpawitwitTahikaw pasohang kunga magwitwit tahayaw(Brothers comelet’s go fishingbecause someone came to ask a favorthat I catch fish.I would want you to helpcome help me catch fish,because someone came to ask a favorthat I catch fish.)

An example of a lullaby is the adang, sung by the Agta of Palanan, Isabela. The soloist sings the adang accompanied by the busog. Rendered in verse with eight syllables per melodic phrase, the song has an arpeggiated melody in ascending and descending contour.

Annin ne annin annin

bemahana a pala pala

Guduhunga ipagtatoy

unduhunga tema tema

Guduhunga tama tama

nungsuhunga palagi da

Lakahana pagi pagi

Wanahaney anni anin

Bamahana Nene, Nene, Neneheneng

Annine, anni, annin

bemahana lallakbayan

Bankahana nema nema

Cuduhunga ema ema

Nungsuhunga Nene,

Nene, Neneheneng.

(Oh! Oh! Oh!

My! the waves.

The child went boating

in the sea.

The shield traveled

because she was left alone

so she left

far away, oh! oh!

My! Nene, Nene, Neneng!

Oh! Oh! Oh!

My! she traveled

by boat alone

The child traveled o’er the big waves

Nene, Nene, Neneng!)

In the town of Malay, Aklan, the pamaeayi, which is the practice of obtaining parental approval for marriage, may occasion the song “Kuti-Kuti sa Bandi”

[Woman]: Kuti-kuti sa bandi,

[Man]: Kuti sa bararayan;

[Woman]: Bukon inyo baray dya,

Rugto inyo sa pangpang.

[Man]: Dingdingan it pilak,

Atupan it burawan;

Burawan, pinya-pinya,

Gamot it sampaliya.

Sampaliya, malunggay,

Gamot it gaway-gaway;

Gaway-gaway, marugtog,

Gamot it niyog-niyog.

Hurugi ko’t sambilog,

Tuman ko ikabusog.

(Woman: Scrutinize the dowry.

Man: Scrutinize the house.

Woman: This is not your

house! You live across the river.

Man: Its walls will be made of silver,

Its roof made of gold,

As golden as the pineapple,

And the root of the bitter melon.

Bitter melon, malunggay,

The root of gaway-gaway;

Beat the drums now

And let’s start the feast!

Drop me some coconuts,

For I am thirsty and hungry.)

Inan uning kulalu ung’Ha ko ha ay takay laman ningbunlongHua ay iya makukokabukilantamaangwaking a gong ditanHako ay naluluwa ikon nako pon nananganHa ay papatulo talon ti hua mataPa-rung hm hmPampanikibat na-an aySumaukan laos ti kaya kong pakidungono lu ako ayako’y magpapa a ganbag song kahit tamalantongKaya kong ipagpalit apunan unKungi kong diling masakit ti lalamunan ayibularlar ko alaw ay iniong ay atong(The birds are chirpingI ate a foul-smelling bagoongHayI am going to the mountains to get ubod,which I will barter for my dinner.I am hungry, I have not eatenIf only my throat weren’t achingI will tell.Oh, mother, oh, father,will spank youHayI think my body is exhausted.)

Ho wa ay kay ti ho ni ko panghuyutanAy yo hay yopan yambutan nining almunganyabi ya bing ya saunghaaykay ti ing panghuyutanpam yam butan alimunganng u mi ya aw kulyawanAy-yay pangambutan alimungan(This is where she caught upAy, hay.My love caught up with me.Late in the night did I goto our meeting place.Ay, hay, love caught up with me.When the kulyawan criedmy love caught up with me.)

HaqaroqAruq uy baking ka iq nangHanggaang ta tala as tasa ayAruy hinlunabing ing ka long au loLin bak nuq ay ti a rap ti a anang diok.(Aru,Why mother?She said,You are pitiful.)

Tatadi’i di’imNa di ta nga dididi’imaninga domobang di’iHi nadida nga kangi di’iEh iy di nga o’ohAda di ka busaw oPatongo o kaminga nag alima nga di toni bayoNami ni ngi di toni(Do not worry that youare placed on the sacrificial platformas offeringat bagobayan omHa do not wish illor pronouncea curse even if omyou await death untileach and allof us have offered dancesto the spirits di’iDo not be hurt that di’iyou will be killed o’ohDo not hex orget even with usbecause no oneis to be blamed)

Wawa dadi danga ingidi’imOmoyo san-o sagaya’on o dingi dingiBongo nado di banangposan di kasan bobayang nga’onTabangga nga dowa nga’om.Ha iba nga ibato di tanaa gingi ingi ingi ngaLinongta tanga tangaingi ingi dingimHa nayon ngo ngonga di na indanango di dinginNa nga’o nga’o da dinaona o pona din donga ongo diga o(This is the first timemy voice dingi dingiis recorded, thatmy presence at bagobayanis being recorded.I wish to say thatthis voice should notbe made fun ofingi ingi dingim.What I havepronounced are thewords dinginof the highestof all the spirits.)

Aeta's Dance Rituals

|

| Monkey dance by an Aeta of Masikap Village, Botolan, Zambales, 1978 (The Dances of the Emerald Isles by Leonor Orosa-Goquingco, Ben-Lor Publishers, Inc., 1980) |

|

| Monkey dance by an Aeta of Masikap Village, Botolan, Zambales, 1978 (The Dances of the Emerald Isles by Leonor Orosa-Goquingco, Ben-Lor Publishers, Inc., 1980) |

|

| Monkey dance by an Aeta of Masikap Village, Botolan, Zambales, 1978 (The Dances of the Emerald Isles by Leonor Orosa-Goquingco, Ben-Lor Publishers, Inc., 1980) |

Documentaries, Films and Videos Featuring the Aetas

ALDAWNetwork. 2012. “Palawan: Our Struggle For Nature and Culture.” via Vimeo.

Amnesty International. 2009. “Mining and Indigenous Peoples of the Philippines: Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Are Human Rights.” Amnesty International. http://www.amnesty.org.nz/ files/Amnesty-International-Taganito-Briefing.pdf.

Arbues, Lilia R. 1960. “The Negritos as a Minority Group in the Philippines.” Philippine Sociological Review 3 (January-April): 39-46.

Arguillas, Carolyn O. 2009. “Largest Royalty Payment to Lumads Divides Mamanwas.” MindaNews, 22 February. http://www.mindanews.com/c87-mining/2009/02/qlargest-royalty-paymentq/to-lumads-divides-mamanwas/.

Aurelio, Julie M. 2009. “‘Nga-nga’ Protest against Laiban Dam Project.” Philippine Daily Inquirer, 31 July. https:www.causes/com/cause/327438/updates/211342.

Balilla, Vincent, Julia Anwar-McHenry, Mark McHenry, Riva Marris Parkinson, and Danilo Banal. 2012. “Aeta Magbukún of Mariveles: Traditional Indigenous Forest Resource Use Practices and the Sustainable Economic Development Challenge in Remote Philippine Regions.” Journal of Sustainable Forestry 31 (7): 687-709. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10549811.2012.704775.

Baluyut, Joelyn G. 2012. “Center for Kapampangan Studies.”Headline Gitnang Luzon, 17 September. http://www.headlinegl.com/center-for-kapampangan-studies/.

Barrato, Calixto Jr. L., and Marvyn N. Benaning. 1978. Pinatubo Negritos. Field Report Series No. 5. Quezon City: Philippine Center for Advanced Studies Museum, University of the Philippines.

Barrows, David P. 1910. “The Negrito and Allied Types in the Philippines.”American Anthropologist 7 (July-September): 358-376.

Bean, Robert. 1910. “Types of Negritos in the Philippine Islands.”American Anthropologist7 (April-June): 220-36.

Bellwood, Peter. 1978. Man’s Conquest of the Pacific. Auckland: Collins.

Bennagen, Ponciano. 1969. “The Agta of Palanan, Isabela: Surviving Food Gatherers, Hunters and Fishermen.”Esso Silangan 14 (3).

———. 1977. “Pagbabago at Pag-unlad ng mga Agta sa Palanan, Isabela.” Diwa 6 (January-December).

Beyer, Henry Otley. 1918. Population of the Philippine Island in 1916. Manila: Philippine Education Company.

———. 1921. The Non-Christian People of the Philippines. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

Beyer, Henry Otley, and Jaime C. de Veyra. 1952. Philippine Saga: A Pictorial History of the Archipelago Since Time Began. Manila: Capitol Publishing House.

Blumentritt, Ferdinand. 1916. “Philippine Tribes and Languages.” In Philippine Progress Prior to 1898, edited by Austin Craig and Conrado Benitez, 107. Manila: Philippine Education Company.

———. (1882) 1980. An Attempt at Writing a Philippine Ethnography. Translated by Marcelino N. Maceda. Marawi City: Marawi State University Research Center.

Brosius, Peter J. 1983. “The Zambales Negritos: Swidden Agriculture and Environmental Change.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 11 (2): 123-48.

———. 1990. “After Duwagan: Deforestation, Succession, and Adaptation in Upland Luzon, Philippines.” Michigan Studies of South and Southeast Asia 2. Michigan: University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies.

Calzado, Conchita. 2013. Interview by R. Matilac. General Nakar, Quezon, 8 and 10 October.

Carolino, Ditsi. 2014. “The March to Progress in the Philippines.” Viewfinder Asia, 4 November.

Catoto, Roel. 2013. “Mamanwa Leaders Nix Manobo Ancestral Domain Claiming Surigao Norte.” MindaNews, 22 October.

Cembrano, Rita. 1999. Todom: Gawa-gawa Apu Nilomboan Kahimonan Ritual, Thanksgiving with the Boar Sacrifice Ceremony. Philippine Oral Epics. Ateneo de Manila University. Accessed 13 October.

Dacanay, Julian Jr. E. 1988. Ethnic Houses and Philippine Artistic Expression. Pasig: One-Man Show Studio.

De la Cruz, Beato A. 1958. Contributions of the Aklan Mind to Philippine Literature. Rizal: Kalantiao Press.

De la Peña, Lilian C. 2014. “Between Veneration and Prejudice: The Ati in the Visayan World, Museum of Three Cultures.” Academia. Cagayan de Oro City: Capitol University.

De la Torre, Edicio, ed. 2005. Significant Change Stories: Caraga Region 13 Mindanao Philippines. CONVERGENCE for Community-Centered Area Development, Inc. and Fundacion IPADE.

Dodds, J. Scott, director. 2000.Batak: Ancient Spirits, Modern World. Film on demand. Lawrenceville, New Jersey: Films Media Group. http://digital.films.com/play/4ZQ8L4.

Eder, James F. 1993. On the Road to Tribal Extinction: Depopulation, Deculturation, and Adaptive Well-being among the Batak of the Philippines. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Empeño, Henry H. 1991. “Living in Limbo.”Philippine Graphic (12 November 1991, 18-19, 39.)

Espada, Dennis. 2003. “Dumagats: A People’s Struggle to be Free.”Bulatlat 3 (24).

Estioko-Griffin, Agnes A., and P. Bion Griffin. 1981. “The Beginning of Cultivation among Agta Hunter-Gatherers in Northeast Luzon.” In Adaptive Strategies and Change in Philippines Swidden-Based Societies, edited by Harold Olofson. Los Baños, Laguna: UP Forest Research Institute.

———.1985. The Agta of Northeastern Luzon: Recent Studies. Cebu: University of San Carlos.

Eugenio, Damiana L., ed. 1982. Philippine Folk Literature: An Anthology. Philippine Folk Literature Series 1. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Folklorists Inc.

Flores, Simplicio, and P. Jacobo Enriquez. 1950.Sampung Dulang Tig-isang Yugto. Manila: Philippine Book Company.

Fox, Robert B. 1952. “The Pinatubo Negritos: Their Useful Plants and Material Culture.”Philippine Journal of Science 81 (September-December): 173-414.

Gaillarde, Jean-Christophe, Catherine C. Liamzon, and Jessica D. Villanueva. 2007. “‘Natural’ Disaster? A Retrospect into the Causes of the Late-2004 Typhoon Disaster in Eastern Luzon, Philippines.” Environmental Hazards 7: 257–70. www.elsevier.com/locate/hazards.

Garvan, John M. 1964. The Negritos of the Philippines. Edited by Herman Hochegger. Vienna: Verlag, Ferdinand, Berger, Horn.

Gironiere, Paul P. de la. 1972. Adventures of a Frenchman in the Philippines, 9th edition. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

“A Glimpse of the Mamanwa Peoples.” 2008. Accesed April 2014. Youtube.

GMA Network. 2013. “Meet the Batak, the Smallest Tribe in the PHL, on ‘I-Witness.’”GMA Network, 6 July. http://www.gmanetwork.com/news/story/316241/publicaffairs/iwitness/.

GMFxStudio. 2013. “Rise Dumagat,” YouTube video, 21 minutes.

Gonzaga, Robert. 2011. “Aetas Fighting for Land Rights Draw Inspiration from Fallen Leader.”Inquirer Central Luzon, 22 August. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/45569/aetas-fighting-for-land-rights-draw-inspiration-from-fallen-leader#ixzz3K0xLsuf3.

Headland, Thomas N. 1975. “The Casiguran Dumagat Today and in 1936.”Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 3: 245-57.

———. 1977. “Teeth Mutilation among the Casiguran Dumagat. ”Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 5 (1-2): 54-64.

———. 1986. “Agta Negritos of the Philippines.”Cultural Survival Quarterly 8 (3): 29-31.

———. 1993. “Westernization, Deculturation, or Extinction among the Agta Negritos: The Philippine Population Explosion and Its Effect on a Rainforest Hunting And Gathering Society.” Paper presented at the Seventh International Conference on Hunting and Gathering Societies, Moscow, Russia, 17-23 August.

Headland, Thomas N., and Janet D. Headland. 1974. A Dumagat (Casiguran)-English Dictionary.Canberra: Department of Linguistics, Research School and Pacific Studies, Australian National University.

Hirth, Friedrich and Rockhill, W.W., trans. 1970.Chau Ju-Kua: His Work on the Chinese Arab Trade in Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries, Entitled Chu-fan-chi. Taipei: Ch’eng-Wen Publishing Company.

Krieger, Herbert W. 1942. Peoples of the Philippines. Washington: Smithsonian Institution.

Kroeber, Alfred L. 1919. “Kinship in the Philippines.” Anthropological Papersof the American Museum of Natural History 19 (3): 69-84.

Lane, Robert F. 1986. Philippine Basketry: An Appreciation. Manila: The Bookmark, Inc.

Lebar, Frank M., ed. 1975. “Negritos.” In Ethnic Groups of Insular Southeast Asia: Philippines and Formosa, vol. 2, 24-31. New Haven: Human Relations Area Files Press.

Lumbera, Bienvenido. 1969. “Consolidation of Tradition in Nineteenth-Century Tagalog Poetry.”Philippine Studies 8 (3): 377-411.

Maceda, Marcelino N. 1964. The Culture of the Mamanuas Compared with That of the Other Negritos of Southeast Asia. Cebu: San Carlos

Publications.

“Manoro: The Teacher (by Brillante Mendoza),” Facebook video, posted by Knowledge Channel, 14 September 2012. https://www.facebook.com/video/video.php?v=10151060364637638.

Marche, Alfred. 1887. Luçon et Palaouan: Six Annees de Voyagesaux Philippines. Paris: Librarie Hachette et Cie.

Miclat-Teves, Aurea G. 2004. Land Is Life. Quezon City: Project Development Institute.

Minter, Tessa. 2010. “The Agta of the Northern Sierra Madre. Livelihood Strategies and Resilience among Philippine Hunter-Gatherers.” PhD dissertation, Leiden University.

Musical Instruments and Songs from the Cagayan Valley Region. 1986. Tuguegarao: Ministry of Education, Culture and Sports.

NCCP-PACT. 1988. Sandugo. Manila: National Council of Churches in the Philippines.

Noval-Morales, Daisy Y., and James Monan. 1979. A Primer on the Negritos of the Philippines. Manila: Philippine Business for Socia Progress.

Novellino, Dario. 2008. Kabatakan: The Ancestral Territory of the Tanabag Batak on Palawan Island, Philippines. Canterbury: Centre for Biocultural Diversity (CBCD), University of Kent.

———. 2014.Update: The Batak (Palawan, Philippines) Digital Archive. Accessed 26 November. https://www.kent.ac.uk/sac/research/files/update_batak_digital_archive.pdf.

Obusan, Ramon. 1991. The Unpublished Dances of the Philippines. Souvenir Program published by the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Manila in conjunction with the event of the same name, 25-26 October.

Omoto, Keeichi. 1985. “The Negritos: Genetic Origins and Microevolution.” InOut of Asia: Peopling the Americas and the Pacific,edited by Robert Kirk and Emoke Szathmary, 121-31. Canberra: Journal of Pacific History.

Orejas, Tonette. 2013. “Fight over Pinatubo Erupts Anew.” Inquirer Central Luzon, 10 March. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/371269/.

Orosa-Goquingco, Leonor. 1980. Dances of the Emerald Isles. Manila: Ben-Lor Publishers Inc.

Padilla, Sabino Jr. G. 2013. “Anthropology and GIS: Temporal and Spatial Distribution of the Philippine Negrito Groups.” Human Biology 85(1): 10. http://digitalcommons. wayne.edu/humbiol/ vol85/iss1/10.

Pamintuan, Marjorie. 2011. “World Environment Day: Protect Philippine Forests.” Inquirer.net, 5 June. http://opinion.inquirer.net/5809/.

Panizo, Alfredo. 1967. “The Negritos or Aetas.”Unitas 40 (March): 66-101.

Paraw, Mala’as Pablo, Mala’as Feliciano Montenegro, Longlong Calinawan, and Berto Gede. 1999. “Tod’om: Gawa-gawa Apu Nilomboan Kahimonan Ritual, ‘Thanksgiving’ with the Boar Sacrifice Ceremony.” Translated by Margarita Cembrano. Katikoyan, Barangay Camam-onan, Gigaquit, Surigao del Norte. Ateneo de Manila University: University Archives System.

Parker, Luther. 1964. “Report on Work among the Negritos of Pampanga during the Period from April 5th to May 31st, 1908.”Asian Studies 2 (April): 105-130.

Peralta, Jesus T. 1977. “Feathers, Leaves and Other Ornaments.” In Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation, edited by Alfredo R. Roces, 2. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc.

———. 1990. “Notes on the Buag Ayta of San Marcelino, Zambales.”National Museum Papers 1(2): 1-40.

Peterson, Jean T. 1977. “Ecotones and Exchange in Northern Luzon.” Economic Exchange and Social Interaction in Southeast Asia: Perspectives from Prehistory, History, and Ethnography, edited by Karl L. Hutterer. Michigan Papers on South and Southeast Asia 13. Michigan: The University of Michigan Center for South and Southeast Asian Studies.

———. 1978.The Ecology of Social Boundaries: The Agta Foragers of the Philippines. Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Pfeiffer, William R. 1975. Music of the Philippines. Dumaguete City: Silliman Music Foundation Inc.

Philippine Entertainment Portal. 2011. “The BIG 10 Films of Cinema One Originals 2011 Festival.” Pep.ph, 18 October. http://www.pep.ph/photos/2655/.

Philippine Panorama. 1973. 14 January, p. 21.

Philippine Touring Topics. 1935. 2 February, p. 10.

Prudente, Felicidad A. 1978. “Ang Musikang Pantinig ng mga Ayta Magbukun ng Limay, Bataan.” Musika Jornal 2.

Rahmann, Rudolf, and Marcelino N. Maceda. 1958. “Some Notes on the Negritos of Iloilo, Panay, Philippines.”Anthropos 53: 864-70.

Rai, Navin K. 1982. “From Forest to Field: A Study of Philippine Negrito Foragers in Transition.” PhD dissertation, University of Hawaii at Manoa.

Ranada, Pia. 2014. “Violence Looms over Ati Tribe Ancestral Domain in Boracay.” Rappler, 26 February. http://www.rappler.com/nation/51635-ati-tribe-security-threat-ancestral-domain.

Red, Ellen. “Lake Mainit and the People Thriving Around It.” 2010. Inside Mindanao, 31 July. www.insidemindanao.com/article154.html.

Reed, William A. 1904. “The Negrito of the Philippines.”Southern Workman 23: 273-79.

———. 1904. Negritos of Zambales. Philippine Islands Ethnological Survey Publications 2. Manila: Bureau of Public Printing.

Reyes, Leonard. 2012. Keepers of the Forest: The Agta of the Sierra Madre Mountains. YouTube video, 11 minutes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v= KpIPoumQJmI.

Reyes-Urtula, Lucrecia. 1981.The First Philippine Folk Festival (A Retrospection). Manila: Folk Arts Theater.

Romualdez, Norberto. “Filipino Musical Instruments and Airs of Long Ago.” Lecture delivered at the Conservatory of Music, University of the Philippines, National Media Production Center, Manila, 1973.

Salinas, Fern. 2008. “Glimpse of the Mamanwa Peoples,” YouTube video, 10 minutes, 17 February. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CeBku4ryrcU.

SBMA Corporate Communications. “SBMA Sets More Projects for Aeta Community.” 2011. Subic Times, 27 October. http://subictimes.com/2011/10/27/.

Scott, William H. 1984. Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

Sebastian, Pedro Cubero. 1971. “Trip to Manila.” InTravel Accounts of the Islands (1513-1787), Tomé Pires. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

Shimizu, Hiromu. 1989.Pinatubo Aytas: Continuity and Change. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Stewart, Kilton R. 1934. “Children of the Forest.”Philippine Magazine 31 (March): 105-106, 125.

———. 1954. Pygmies and Dream Giants. New York: W. W. Norton and Co. Inc.

Swiderska, Krystyna, Elenita Daño, Olivier Dubois. 2001. Developing the Philippines’ Executive Order No. 247 on Access to Genetic Resources. London: International Institute for Environment and Development.

Tomaquin, Ramel D. 1987. “Tribal Filipinos, Ancestral Lands, and Cultural Survival: Or the Negrito Case.” Pilipinas 9: 1-9.

———. 2013. “Indigenous Religion, Institutions and Rituals of the Mamanwas of Caraga Region, Philippines.” Asian Journal of Social Sciences, Arts and Humanities 1(1): 21-23. Tandag City: Surigao del Sur State University.

———. 2013. “The Mining Industry and other Development Interventions, Drivers of Change in Mamanwa Traditional Social Milieu in Claver, Surigao del Norte: A Case Study (Philippines).” American International Journal of Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences 5(1): 85-89.

Tribal Channel. 2016.Tribal Journeys: The Agtas. YouTube video, 26 minutes. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XNrzuELmZTY.

Trinidad, Ariel. 1992. Interview by R. Matilac. September.

Vanoverbergh, Morice. 1937-1998. “Negritos of Eastern Luzon.” 2 parts. Anthropos 32: 905-28; 33: 119-64.

Vergara, B. M. 1995. Displaying Filipinos: Photography and Colonialism in Early 20thCentury. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Video 48. 2008. “Rosemarie-Pepito Rodriguez Love Team Circa 1965-69.”Video 48, 1 August. http://video48.blogspot.com/2008/08/.

Villaruz, Basilio Esteban. Sayaw: A Video Documentary on Philippine Dance.Tuklas Sining series, directed by Ramon Obusan (1989; Manila: Cultural Center of the Philippines). Documentary film.

Virchow, Rudolf. 1899. “The Peopling of the Philippines.” Washington: The Smithsonian Institute.

Warren, Charles P. 1964. The Batak of Palawan: A Culture in Transition. Research series 3. Chicago: University of Illinois Undergraduate Division.

Whittle, Claudia, and Ruth Lusted, comps. 1970. Bunnake, Atta Riddle Book. Manila: Summer Institute of Linguistics Philippines.

Worcester, Dean. 1898. The Philippines. New York: Macmillan.

Yap, Fe Aldave. 1977. A Comparative Study of Philippine Lexicons. Manila: Institute of National Language.

3 comments:

Hello ! I would like to know from which book/article comes the legend of origins displayed in this post and whether there are more Aeta stories that were recorded and translated. Thanks for this interesting post !

Hello ! Thank you for this interesting article. I would like to know from which book/article the tale of origins displayed in the article comes and whether there are other Aeta tales that were recorded and translated.

do you have copy in pdf?

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?