Ata Manobo Tribe of Davao del Norte: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group]

The Ata Manobo, also known as Ataas or Agtas, are found in the northern part of the municipality of Kapalong, Davao del Norte. Many of them, however, identify themselves simply as Manobo or by their toponyms such as Matiglondig, meaning “from Londig;” Matigkapugi, “from Kapugi;” or Matigmisulung, “from Misulung.” Historically, “Ata” was a derogatory term used by the Spaniards to refer to all peoples living in upland areas, regardless of cultural or linguistic differences. It is not even in the Ata Manobo vocabulary; thus, it is meaningless to them. The Ata Manobo language is identified as a subgroup under the Manobo group of languages, specifically categorized by Dr. Richard Elkins as Proto-East-Central Manobo.

There are three identifiable Ata Manobo tribes: the Matigsalug, the Talaingod, and the Matig-Langilan. The Matigsalug, meaning “people of the river,” are in the municipalities of Kitaotao and San Fernando in Bukidnon; in Arakan Valley, North Cotabato; and in the Marilog and Paquibato Districts in Davao City. In 2000, their population was estimated at 26,700. The Talaingud, meaning “people of the land,” are in the municipality of Talaingod in Davao del Norte, its borders touching Kapalong, Bukidnon, Davao City, and Santo Tomas. The population estimate of the Talaingod in 2010 was 25,566, but this figure was based largely on their population in the municipality of Talaingod alone and may not have taken into account those who have spread to other regions because of migration or forced evacuation. Subgroups of the Talaingod are called Talalangilan or Matig-Langilan, meaning “from Langilan.” The scattered groups living around Mount Misimulong are called the Talakoilawan or Kaylawan, meaning “from the forest.” In Cotabato alone, the Ata Manobo were estimated at 41,862 in the year 2000.

History of the Ata Manobo Tribe

The first historical account of the Ata Manobo appeared in 1881, when a Spanish missionary mentioned the group as one of those inhabiting areas along the Tuganay River and Ising Creek in Carmen, Davao del Norte. Father Gisbert had planned to proselytize the tribe but changed his mind because of accounts of vendettas and killings. Jesuit priests later realized that the attacks waged by the Ata Manobo were not aggressive but mainly retaliatory, as their loose social organization made it difficult for them to initiate more strategic raids. The Ata Manobo were largely nomadic groups, tending to live in single family units far apart from each other, which made them highly susceptible to slave raiders.

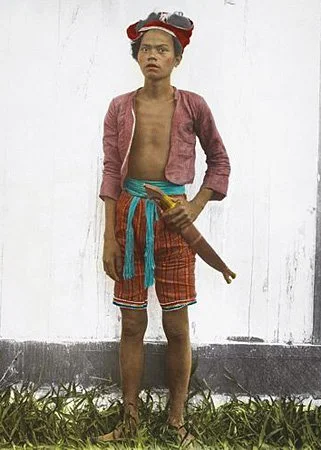

|

| Young Ata (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

In the early 1900s, the American Governor-General Bolton classified the Tugauanon, a group originating from Ata settlements along the Mapula River, as “Ata” because of perceived linguistic similarities with the Tagauanum Ata.

The oral histories of the Matigsalug point to the mouth of Salug River, now Davao River, as their original settlement, before marauding groups pushed them to the upper areas of the river, as far as the Bukidnon uplands. They were objects of slave raids and were used in human sacrificial rites by the Bagobo and Jangan or Guiangan. Yet the Matigsalug were not without their share of warriors. Datu Gupaw of San Fernando, Bukidnon once defended their lands from the Maguindanaon by allying with the Obo Manobo. Through this collaboration, they succeeded in forging a peace pact with the Maguindanaon.

The American colonial government declared slave raiding and other trading activities illegal and established military headquarters in Moncayo, Mampesing, Mati, and Davao to enforce colonial law. A surrendered bagani (warrior) called Macusang was appointed as the presidente del distrito municipal of Cambanugoy, now Asuncion, with jurisdiction over the Salug River Valley and Moncayo. His principal duties included the “pacification” of all baganito make them give up their pangayam and ludyo (spears), and their kakana and pinuti (fighting bolos).

The colonial government encouraged American and Japanese entrepreneurs to develop coconut and abaca plantations in the lowlands. Luzon and Visayan laborers were recruited as plantation hands, resulting in an influx of settlers and the forced evacuation of the original inhabitants to the hinterlands. The Commonwealth Government furthered internal colonization when it promoted Mindanao as a “Land of Promise,” enticing more settlers from Luzon and the Visayas with its description of Mindanao’s “vast, uncultivated lands.” However, such stock phrases were actually referring to the ancestral domains of the Ata Manobo and other lumad (indigenous) groups (Nabayra 2014).

Ata Manobo lands were taken from them either by force or deception, and transformed by the migrant settlers into lowland rice and cornfields, abaca and coffee farms, and banana plantations. Recovery of these lands became more difficult in the 1950s when the Philippine government began issuing logging permits to multinational companies. Centuries-old dipterocarps were harvested for export, effectively legalizing the land grabbing of Ata Manobo ancestral domains. The 1950s and 1960s saw the entry of large mining corporations, logging companies, and other extractive industries in Mindanao, whose operations resulted in vast environmental destruction and the denudation of forests and watersheds (Nabayra 2014).

In the 1970s, Datu Lorenzo Gawilan, whom the Matigsalug recognize as one of their greatest heroes, rebelled against the encroachment of ranchers into their ancestral domains. He led his people in a fierce struggle against the foreign landlords, whose claims to the land were protected by the state through the Philippine Constabulary (PC). Whenever Datu Gawilan killed a PC soldier, he marked the body with a fierce avowal: “Dili mi pahawaon sa among yuta” (Do not drive us from our lands). Barrio Lorega in Kitaotao, Bukidnon is named in his honor. “Lorega” consists of the first two syllables of his first name, Lore, and the first syllable of his last name, ga (Tiu 2005, 73-74).

The indigenous peoples’ struggles against the encroachment and plunder of multinational corporations intensified in subsequent years. This brought about the rise of organized resistance groups, which in turn led to increased militarization in the region. In 1993, the Talaingod in the Pantaron Range fought against the entry of mining and logging companies in their ancestral domains. Isolated conflicts escalated into a war involving aerial bombings, indiscriminate firings, and human rights violations, many of which were attributed to military and paramilitary forces. Thousands of Talaingod families were forced to evacuate their homeland. In 2015, after a series of killings of known lumad leaders by paramilitary groups, Talaingod evacuees launched a caravan that mobilized almost a thousand lumad to travel from Mindanao to Manila, to draw attention to the plight of indigenous peoples in Mindanao (Arkibong Bayan 2014; MindaNews 2014; Manilakbayan 2015).

The Ata Manobo continue to struggle to preserve their ancestral domains, besides having to confront major problems—the erosion of their cultural practices and traditions which caused their exposure to non-lumad practices and different religions; massive poverty; their exclusion from the nation-state’s development projects; lack of access to quality and higher education; the persistence of armed conflict in the region and the militarization of Ata Manobo lands; and the exploitation of their resources by large logging companies and other business corporations.

The Ata Manobo Way of Life

Since the precolonial period, the fields, forests, and rivers have been the Ata Manobo’s principal sources of food. To trap game, an Ata Manobo hunter may set a lit-ag for wild chickens, loyloy for wild deer and monkeys, or bawod for others. They use the bogyas to catch freshwater fish in the rivers and streams. The use for fishing of tubli, a kind of poison made from the bark of a tree, meets with collective disapproval because the poison kills even the fish eggs and fingerlings. Among their taboos, the Ata Manobo believe that eels with eggs must be returned to the water because bringing them home may bring about the death of a child in the family.

Hunting and fishing are done within the territorial jurisdiction of the hunter’s community to avoid violations of boundary agreements. However, prevalent deforestation by big logging companies and swidden agriculture have severely limited many of these practices.

The Ata Manobo’s dominant means of livelihood is kakamot (swidden agriculture). Forest growth is slashed and burned to clear areas for tilling and planting; when the crops are harvested, a different space is cleared for the next crop. Before kakamotis undertaken, the igbujag no datu orders the menfolk to inspect the forest if the kapayawi trees are about to sprout new leaves or if the narra trees have already shed leaves because these signify that it is the appropriate time for slashing. If these conditions are fulfilled, the baylan leads the community through the swidden rites, offering a panubad (prayer-offering) to the deities Kallajag and Igbabasok, protectors of agricultural crops, to ask their permission and blessing for the undertaking. Likewise, the seeds and farm implements are prayed over. After this, the men proceed to the area for slashing. To test if it is, indeed, all right to start in the specified area, a man cuts some grass and ascertains the consent of the deities through the response of the alimukon (turtle-dove). Before clearing the fields, the Matigsalug offer up a chicken as sacrifice to the deities of the forest in a ritual called padugo (to bleed).

The constellation guides the Manobo’s agricultural activities. For the Matigsalug, the appearance of Pandarawa and Baga, which signal the coming heat, marks the commencement of kaingin; the star Balatik, believed to guard crops against pests, marks the commencement of planting; and the star Gibang, which signals the start of the rainy season, marks the end of the planting season. The crops are harvested upon the ripening of the grains, but not before another thanksgiving panubad, in which betel nut, at least 10 chickens, and a pig, are offered up to the supreme deity Manama or Mangama.

The operations of large logging companies, which were especially aggressive between the 1970s and 1990s, have destroyed many of the lands of the Ata Manobo. The companies cut timber from site to site, taking not only the valuable resources of the Ata Manobo but also another source of their livelihood: cutting and selling timber. The destruction of Ata Manobo ancestral domains has caused severe losses of wild game and fish. Hence, they have resorted to domesticating animals such as poultry and cattle in place of their hunting activities. Only years into the new millennium would rehabilitation efforts see regrown timber and wild game slowly return to Ata Manobo forests.

Tribal System of the Ata Manobo People

The Ata Manobo have three key political figures: the datu, the baylan, and the bagani. The datu functions as the adviser of the community and is in charge of maintaining peace and order. The bagani also maintains the peace but is subservient to the orders of the datu and the baylan. The baylan serves as the religious leader, diviner, and healer in the community. A later addition to this group is the bai or biyo, the female counterpart of the datu. In some communities, there is an apo (elder), whose wise counsel is heeded.

In the early Ata Manobo society, the head of the community was called the igbujag or igbuyag, meaning “leader,” a position typically granted to the oldest member of the community. Among the Talaingod, the leader was called the manigœ-on. When the Commission on National Integration was created in 1954, a special committee was formed mainly to address the growing problem of Muslim separatism in Mindanao. Under the assumption that “datu” was the generic term for all indigenous leaders in Mindanao, or in the whole Philippines for that matter, the committee erroneously used this term to refer to the Ata Manobo igbujag datu or igbujag no datu (Industan 1993, 142; Nabayra 2014).

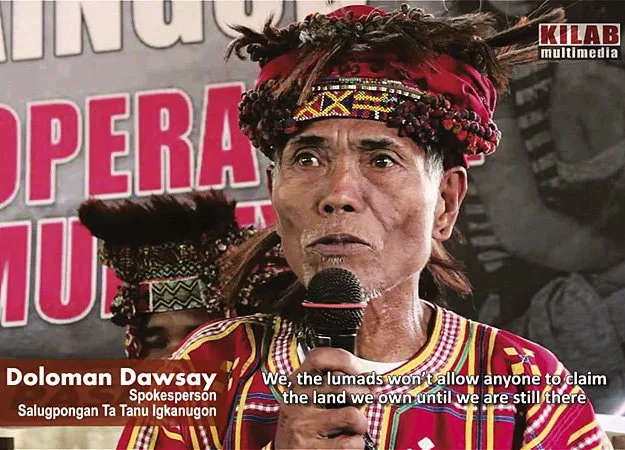

|

| Talaingod Manobo leaders defending their ancestral domain, 2014 (Leo A. Esclanda/Boy Bagwis) |

The igbujag no datu is generally accorded the highest authority in Ata Manobo societies. His functions are at the center of governance. He sees to the observance of customary laws, the litigation of raiding cases, marriages, and debts, and the gathering of the community for meetings and assemblies. The datu may be chosen by consensus among community members, or the position may be bequeathed by a previous igbujag no datu to one who he thinks would be a capable successor. Among the Matigsalug, “igbuyag” refers to the community elders who, with the support of the community, select the datu based on the ideal qualities of bravery, fairness, wisdom, and compassion. Although succession of kin is not a strict requirement, kinship by blood or marriage is given priority.

The ideal igbujag no datu is a native Ata Manobo and a model of good behavior. He is peaceable and concerned with the welfare of the community. He is wise and articulate in expressing his ideas so that he commands the respect of all. He is skilled in facilitating and settling conflicts but is willing to solicit the help of others when he has a problem that he is uncertain how to address. He is industrious, as evidenced by the number of his livestock and quantity of farming produce, and he regularly attends meetings of tribal leaders.

Crimes and offenses in the community are mediated by the hibatoon no datu (lower datu); more complex cases are elevated to the igbujag no datu. Perpetrators are punished under the guidance of customary law, with punishments ranging from fines and penalties to death, depending on the gravity of the offense. In Matigsalug communities, grievous domestic conflicts such as wife beating or adultery can culminate in divorce.

When there are conflicts between communities or members of different communities, the leaders of the involved communities confer. Conflicts are resolved through bilo (peace settlement) or pangayaw (revenge killing or vendetta).The traditional concept of justice is called tihian or “supreme justice,” consisting of several tests that are overseen by the igbuyag. Among the Talaingod, a group of datu called a salugpungan (union) and a council of manigœ-on elders conduct husay (arbitration) over complex problems, but the manigœ-on take responsibility for the final verdict.

The baylan, also bailan, is the recognized religious leader of the Ata Manobo community. He or she is an elder believed to be chosen by or infused with the spirit of a bantoy or abyan (spirit guide). The baylan can have several functions and abilities. As a medium, the baylan leads prayer rituals and acts as a mediator or negotiator for the community with the bantoy. The baylan is a healer by touch and prayer, or by securing medicinal herbs dictated by a bantoy through dreams. The baylan is also a religious leader who cares for the spiritual needs of the community and interprets the pronouncements of bantoy through other baylan. The baylan’s other functions are educator, adviser, and evaluator who assists in teaching customary laws.

The bagani are warriors who assist the datu in facilitating community welfare and observance of customary laws. In many cases, the igbujag no datu himself is a bagani. They are figures of strength, bravery, fearlessness, and skill. Not only are they protectors of the community from external aggression; they also become aggressors against offending parties or communities if circumstances demand it. They mobilize the community for pangayaw if initial confrontations or dialogues with an offending party fail. Recent additions to the functions of the bagani delegate them as protectors of the ancestral domain, rectifiers of incorrect or improper behavior toward authorities or other persons, and the implementing arm of the mandates of the igbujag no datu.

The position of the biyo or female leader is not announced or formally declared, and not all Ata Manobo communities have a biyo. However, having a biyo in the community is a privilege as she undertakes roles ordinary women cannot fulfill. The biyo assumes the functions of a datu in his absence. She participates in deliberations on family and community problems and is part of the decision-making process of the community. A biyo offers advice when it is solicited and helps in educating the women of the community. She attends to guests from other communities on special occasions and graces tribal or community events as a representative of her community.

Some Ata Manobo communities have an elder as a leader called apo who is consulted for advice or opinions in extraordinary circumstances. He usually stays in the background of community issues, unless he is at the same time the chieftain. As the oldest and one of the most respected members of the community, it is to him that the community turns for the narration of past events in order to gain some insight from their history and avoid errors previously committed.

Over the years, the traditional political structure of the Ata Manobo has changed radically, largely because of the interventions of the nation-state. In the 1970s, President Ferdinand E. Marcos formed the Presidential Assistant on National Minority (PANAMIN), ostensibly to take charge of the affairs of indigenous peoples of the country. Manuel Elizalde Jr., whose family owned the industrial conglomerate Elizalde and Co, was appointed as Department Secretary. The PANAMIN divided the indigenous peoples into arbitrary settlements and appointed datus, who were assisted by a council of elders, to head them. They made these appointments official by holding rituals to install them as community leaders (Nabayra 2014).

Acculturated Ata Manobo societies also began to recognize the barangay captain, an expression and mechanism of state bureaucracy, as a figure of authority. In the 1970s and 1980s, the barangay captains shared the same functions as the igbujag no datu, although the datus were still more revered (Industan 1993, 145). The apo’s authority was also reduced due to the presence of barangay leaders, whose functions, embodied in the Local Government Code, coopted the apo’s traditional roles, which were to settle differences among members of the community and to plan projects for each community. The apo’s principal authority is now limited to giving private advice when disputes occur. The barangay captain continues to be consulted especially in matters pertaining to outsiders and conflicts with lowlanders.

President Corazon C. Aquino, during her term, turned the PANAMIN into the National Commission on Indigenous Cultural Communities (NCIP), whose main purpose is to implement the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Acts of 1997, especially the provisions on ancestral domains.

The Ata Manobo’s traditional way of settling conflicts is through the pangayaw, which may be waged between individuals, families, or communities and is triggered by a grievous transgression such as murder, dishonor, or violation of an agreement.

Pangayaw may typically occur in four ways. The first is panalowsow, when a man accidentally kills another out of anger or grief. This provokes the injured party’s family and takes a long time to settle. The second is pamalo, when one community wages pangayaw against another because the former suspects the latter of conspiring to harm them. Notice of an impending pangayaw is sent to the igbujag no datu and to members of the suspected community through a kurow (calendar), a strand of knotted rattan tied with a red piece of cloth. The knots indicate the number of days that the targeted individual or community has to prepare for the pangayaw. The third way is a’mara, where the datus of various communities to settle a conflict through bilo or pangayaw. The fourth is panglibak, when an individual, who feels that he was unfairly compensated in a conflict resolved through a mediator, wages pangayaw against the person who had failed to give him his fair share.

Pangayaw is normally scheduled after the sowing of seeds or the harvesting of crops. No pangayaw is undertaken before harvest time because the ripening crops would be damaged in the resulting melee between the warring parties. However, the abduction of a spouse by another can trigger a pangayaw at any time of the year, even without prior consultation with the chieftain.

The pangayaw was traditionally intended to protect lumad territories from encroachment and destruction, although in recent years, its meaning and function have been distorted as it has been used for counter-insurgency initiatives and security for business purposes.

Ata Manobo Tribe Social Organization, Customs, Traditions and Culture

Ata Manobo families have a bilateral kinship structure in which both sides of the family reciprocate each other in fulfilling familial responsibilities. The mutual sharing of duties between the two sides of the family is a way to strengthen ties and maximize limited resources.

The men hunt and fish, cut down trees for kaingin, plow the field, and arrange suitable marriages for their children. The females do much of the domestic chores such as fetching water, gathering firewood, and taking care of the children. On the kaingin field, they do the planting, weeding, and harvesting. Meanwhile, the datu and baylan participate in the education and discipline of children.

Polygyny is allowed, depending on the husband’s capacity to afford the gastu (bride-price). Among the Matigsalug, the practice of duay or the taking of another wife is subject to the approval of the first wife, who has the prerogative to choose the secondary wife. Subsequent wives cannot refuse the duay. However, very few Ata Manobo men can even afford a second wife.

|

| Ata Manobo family, circa 1990 (SIL International) |

There are several types of courtship and betrothal among the Ata Manobo. Tinuyu, meaning “done on purpose,” refers to a marriage prearranged by parents or elder siblings through a pamaloy (formal arrangement). The Matigsalug term for this practice is bugay. A bride-price is negotiated and settled between the parents of the boy and the girl, and the boy’s family renders the bride-price to the parents and kinsmen of the bride upon their marriage at the age of puberty. Arrangements between cousins up to the third degree are not allowed, as these are believed to cause illnesses and congenital deformities in the offspring. In the few cases where marriages are not prearranged, an adult male may choose his own bride, provided that his father formally talks about it with the girl’s father. In rare and more recent instances, a woman could also choose her own husband and inform her father of her choice (Industan 1992, 4; Burton 2014).

A bogkot is a marriage arranged when a father wants a couple-neighbor to be the parents-in-law of his son. Without revealing his intentions, the father would offer the desired parents-in-law various gifts until the value amounts to a sufficient dowry. The boy’s father would then undertake a gesture of intent called pamoka to the girl’s father, enumerating all that he has given to ensure their agreement to the marriage proposal.

There are also cases of bulansong, in which a third party covertly finds out the girl’s bride-price for the interested groom, and the groom bypasses the pamaloy by immediately bringing the gastuto the girl’s family and asking for her hand in marriage on the spot (Industan 1992, 5). A male may also acquire his bride by rendering panawas for his prospective parents-in-law. He would serve in their household until he has proven his mettle, then he will be asked to fetch his father to discuss the duwaron (dowry), the togonan (expenses to be incurred for the wedding), and the date of the wedding, which would be indicated on a kurow.

There are forced marriages through lokkoban, meaning “to shut off,” when a boy is forced to marry a girl whose parents have set their sights on him as a son-in-law. This may occur when a boy remarks favorably on the girl’s village, as this can be interpreted to mean that he wants to live there. The family then prevents him from leaving, sometimes under threat of death, unless he agrees to marry their daughter. When he accedes, he will be sent home with a gift called tukiab to lokkob from his in-laws to his parents, who will then deliver a token of acceptance called isugbak, in lieu of a bride-price (Industan 1992, 5-6).

Marriage may also be forced in cases of pinu-uan, which means “to sit down,” when a boy has touched a girl, whether deliberately or accidentally, and is thus forced to marry her. Gestures such as borrowing a girl’s comb, walking over the legs of a seated girl, touching the fingertips of a girl, and touching a girl’s shoulder blades are deemed as acts of interest and intent. Traditionally, Ata Manobo also practiced alig (courtship) by exchanging messages through the kubing / kobbing (mouth harp), although this may not necessarily end in marriage (Industan 1992, 6-7).

Tinangag, meaning “to carry something without permission,” is also a kind of forced marriage, either by the couple’s elopement or by the man’s “stealing the girl for a wife.” The latter is more culturally accepted, as it is done with the encouragement of the boy’s family. It proves that the boy’s family is well-off, as they can pay any bride-price that the girl’s family demands. This is called pogpolod to baloy, meaning “collapsing of the house” (Industan 1992, 7).

While the wedding arrangements are being made, the man’s father brings with him the following items: a chicken, a comb, a beaded leglet, a bolo, a necklace, a female blouse, and anything that may be of value to the girl’s family. These ornaments may be worn by the girl during the wedding ceremony.

|

| Manobo wedding in Davao, circa 1981 (Filipinas Heritage Library) |

Wedding ceremonies are performed in the hut of the bride by the igbujag no datu of the bride’s community. When the dowry has been turned over to her parents, the bride’s relatives fetch her from a neighbor’s hut, and she approaches the wedding hut under the shade of a torongan (blanket) held aloft at each end by aides. Upon arrival at the newly constructed hut of the couple, a member of the family covers her head with a mantabla (white veil). An ikam (mat) is laid out at the center of the room, with the bride’s father seated beside the groom and the groom’s mother seated beside the bride. Each parent molds a fistful of cooked rice or camote (sweet potato) with their hands and gives these to the groom and the bride. The two then feed each other. The datu prays over the couple and invokes Tagonliyag for their successful marriage. He, followed by the groom’s father and other relatives, offers them a litany of advice. The ceremony is followed by feasting and merrymaking, with the guests dancing to the tune of the kudlong .

The couple may not yet live together as husband and wife after the wedding ceremony. The groom has to live with and render service to his in-laws before he returns to his bride. This is called panganogang. Among the Matigsalug, the groom has to undertake the panakin, the opening of a new swidden farm to be planted with various crops, in order to prove his capacity to provide for his wife and future family. The wedded couple builds their own house only after their first child is born. In other Ata Manobo communities, the couple lives with the family of the girl first in order to learn from her parents their marital roles and responsibilities. When they are given leave to build a life together, the husband leaves a gift with his parents-in-law called masaakit no goinawa, meaning “to heal the pain of their absence.” However, because of the influence of settlers and outsiders, younger generations tend not to follow these practices strictly (Industan 1992, 8; Burton 2014).

Expectant mothers consult the baylan before, during, and after pregnancy. The baylan recommends the kinds of food that a pregnant woman may eat, as these are believed to affect the ease of delivery of the child and even its physical appearance. They believe that eating the inner meat of animals weaken the child’s health, that eating eels and shrimps can delay delivery, and that eating cassava will result in a small baby with a big stomach. Thus, fruits and other nutritious food are primarily recommended for pregnant Matigsalug women. During childbirth, charms, herbs, stones, and other items recommended by the abyan are tied around the mother’s waist. The baylan cuts the umbilical cord with an ilab (knife), and the cord is wrapped in a mat and kept under the stairs of the house. Family and relatives wait outside the birthing house to welcome the newborn.

The Matigsalug children are named and integrated into the community through gunting (circumcision), pangutob (tattooing), and the chewing of mama (betel nut). A boy is circumcised at two years old with the use of a bignos or ilab. Herbal plants are used to hasten the healing of the wound.

During wakes for the dead, the baylan performs songs, and members of the community recite the oranda (extemporaneous renditions) that narrate the positive traits of the dead and elevate him or her as an example for others in the community. If the dead is male, a spear is placed alongside the body during the burial; if female, a pestle, signifying the work of pounding rice. When the body is buried, the baylan may conduct a panubador pangapog, in which the dead is implored not to regret leaving this world or worry about those left behind, and to help ensure the continuance of peace amongst the members of the family and the community.

The Ata Manobo bury their dead so the busaw (blood spirit) cannot see the corpse and devour it. The dead may be left unburied if the people wish to be reminded of the deceased person’s positive qualities and noble deeds. If the body is left unburied, it is placed inside a binobo (coffin) made of the lower half of a hollow trunk of an almaciga tree, with the upper half serving as cover. To seal the coffin and prevent the smell of decomposition from escaping, the Ata Manobo use the latex of the bayog or kabalikod tree or the scraped bark of the lungay tree and its resin. The coffin would then be hung horizontally on four crossed branches of a tree, and a roof made of leaves of the trees or plants is set up to protect the coffin from the elements.

Immediately after the person’s death, the body may be placed in a coffin and left in an abandoned hut far from the neighborhood. If the body is not placed inside a coffin, it is wrapped in the bark of the dangolog or the kapayawi tree and laid on a bed of manogo leaves in a knee-deep grave dug in the forest.

Ata Manobo adults still adhere to the centuries-old practice of betel chewing. The betel chew or mamais a mixture of bunga nut, buyo leaves, and lime. It serves to strengthen the teeth and is a substitute for food. The inch-long tobacco cud called suro placed between the teeth is another familiar habit of the Ata Manobo. The women chew suro while one end juts out from their lips, while the males keep it inside their mouths, looking like lumps on their cheeks.

Across the Philippine islands, the bamboo tube is the traditional container for cooking dishes. The first written record of this was in 1525 by Magellan’s chronicler Pigafetta, who observed it in Palawan. He remarked that rice cooked in bamboo lasted longer than that cooked in clay pots. The Ata Manobo had 18 varieties of rice, which they cooked tinalumbo (in bamboo tubes). Dishes wrapped in leaves are called binugsung. The Matigsalug use the foot-wide leaf of the alik-ik / hagikhik in Samarnon, for their sticky rice cakes, or the round leaf of the bongabong (parasol tree) as food wrapper before roasting a dish over the fire or cooking it in the bamboo tube. Famine foods are the heart of the mabul (fishtail palm tree), which is tasteless, and heart of the rattan, which tastes bitter; hence, these are eaten only as a last resort. For the Matigsalug, an added ingredient to the minced dishes cooked in bamboo is the tiny heart of the dalikan (tagbak or tugis in Bisaya).

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Ata Manobo

The Ata Manobo believe in a world of spirits which inhabit the heavens, the earth, and the nature surrounding them. In their cosmology, the kalibutan (earth) used to be just a kimonò nu mundù (rounded mass of cooked sweet potato) before Bibu, the master of the world of the dead, filled the earth with leaves, which rotted and turned to mud. Gamowgamow, the deity of light rains, built a hole to contain water, and the gods and deities began to plant things on earth. Finally, Manama, the Supreme Being, gave it light so man could determine the seasons.

|

| Ata Manobo ritual (SIL International) |

Manama, also known as Magbubuot, Magbobo-ot, Mababaya, or Maminturan, is the creator of life, the heavens, and the earth, and the guardian of mankind. In Matigsalug cosmology, he is believed to preexist all other life forms, living alone in a place called Lingawayni until he decided to create all the other deities,who became his helpers in creating the world and man (Burton 2014). It is to him that the panubad is first directed, either to express gratitude and trust or to entreat him for good health and protection. He also provides power to the other deities and the bantoy.

|

| Ata Manobo ritual (SIL International) |

Other deities are invoked for specific roles and functions. Igbabasok, who owns the food for subsistence, and Kallajag or Kalayag, who owns the sun, moon, and stars, are entreated for safety and guidance in farm work, for the protection of crops, and for abundant harvest. Karang owns the people’s sabinit (clothing) and is called upon for the protection of work animals. Solojob is invoked for a successful hunt; Talabobong or Tagsukod for the success of hunting traps; Palopo and Timbalong for the protection of chickens; and Pamulingan, with Igbabasok and Kallajag, for the protection of plants. Alimongkat or Alimugkat, the deity of rivers and heavy rains, lives with his wife, Gamowgamow, in streams and rivers. They are invoked during diving or fishing expeditions. Tagonliyag is entreated for guidance in love and success in marriage. Mandalangan, a blood spirit, is prayed to for courage before a pangayaw. Deities also command breath: Makabibitil allows breath to continue while Hagtonganon decides when to make it stop (Industan 1993, 159-160).

Bantoy or spirit guides dwell between heaven and earth to mediate between the baylan and the deities. This is because Manama cannot come to earth due to the ngarog (stench or odor) of mankind’s sin. There are good spirits with the power to heal illnesses and cast out bad fortune, and bad spirits that live in trees and inflict ailments on those who incur their ill will. The baylan serves as the medium for the bantoy to communicate messages from the deities to the people (Industan 1993, 161-164).

The Ata Manobo believe that their dreams at night are the handiwork of spirits communicating with the living. There are two kinds of dreams: when the dreamer is unconscious and when the dreamer experiences the dream as if he were conscious. In the latter, it is the nanawan (spirit) that allows a dreamer to separate from his physical body and leads him to explore other places in dreams.

The gimokod (soul) is what goes to the otherworld after death. The gimokod of honorable men travel to another world called Liwanon at the bottom of the earth. The dishonorable’s soul goes to the deity Moibulan for punishment or purification. In other accounts, the ruler of the world of the dead is Bibu, and his domain is under the earth, where he teaches souls to be morally upright, perfect, and fit to stay in langit (heaven). Langit has rivers full of fish, large houses, and a bounty of plants, and the lowlanders and tribes are segregated from each other (Industan 1993, 163).

With the coming of the missionaries from different Christian sects like the Roman Catholics and the Evangelical Protestants, many of the Ata Manobo have been converted to Christianity. While rituals are still performed during special occasions such as planting and harvest seasons, the spiritual leadership of the baylan has been greatly reduced because of religious prohibitions by the new churches (Burton 2014).

Ata Manobo Community and Indigenous House

The Ata Manobo originally lived in small communities of two or three families. The traditional Talaingud community structure was called the ugpa-anan or ingud. These communities were kept small so that the members could move fast to escape raiding forces. While thick vegetation typically separated one ingud from another to confuse the enemy, the Talaingod still tended to build their homes at least within shouting distance of each other. A cluster of ingud is called a salugpungan or long house (Nabayra 2014).

Manobo families lived in makeshift huts built high above the ground to protect them from enemies. Pieces of rope were twined to serve as stairways, which could be raised up at night so no one could climb up. In later years, the huts were built lower, becoming elevated one-room dwellings usually made of cogon. The walls were built with barks of trees or dried palm fronds, the floor of split bamboo strips, and the posts of wood or bamboo, bound with rattan strips.

|

| Ata Manobo indigenous house (Gary Pombo) |

To select the site on which to build their house, the Matigsalug look for a puahol tree with leaves that are green on the topside and white on the underside. On the tree, they find a sanga silangan or a branch pointing east with six leaves clinging to it. The six leaves represent the deities who control the domains of the environment: earth, fire, river, mountain, springs, and rocks. The head of the family then places the branch on his proposed cornerstone for the house and waits for a night to pass. At daybreak, if the leaves are still intact, it means that the deities have given their blessing for the construction; if not, the family needs to find another place to build the house.

Before cutting the bamboo poles to be used as building materials, the Matigsalug builder rubs ginger onto the part of the bamboo that will be cut. This is done on a moonless night because it is believed that this prevents insects from attacking the cut bamboo (Quimpo et al. 2003).

Matigsalug houses have walls of either lakap (split bamboo) or woven bagakay (reed). Roofs are thatched with cogon grass. The datu’sresidence, called balay kalibolongan ,serves a special function in the Matigsalug community. It is a square two-story structure that serves as the assembly hall, besides being the residence of the datu and his family. On the first floor are the lasod, the family residence, and the abuhan (fireplace). It is where the datu holds discussions with the igbuyag and councilmen. The first floor has a lantawan (window) all around it. A few ascending steps lead to the second floor, which has the sinabong (married couple’s room)and the sinabong sa mangubay (unmarried daughters’ room). A recent addition to the traditional Matigsalug house is the ilutuan-koonon (kitchen-dining room)

The present form of the datu’s residence has already been influenced by lowland culture and technology, although it still bears traces of its indigenous character. In traditional Matigsalug architecture, the different parts of the house are either attached to each other by wooden pegs that are driven into holes or tied together by liway (rattan) strips. The various specific patterns and techniques used to tie the rattan strips not only secure the house but also create a decorative effect. Nails and other modern construction materials, however, have replaced the liway and the wooden peg.

A himulayan is an anteroom to the datu’s residence. Along its sides are built-in seats, and above it is a loft area for resting and sleeping. Next to the balay kalibolongan is the lulapong (granary), built and designed to keep vermin and pests out. It is fully enclosed and raised four to five meters above the ground by a single post at the center. Beams or poles arranged like the spokes of a wheel, with the single post as the hub, hold the granary up. The walls are made of lakap.The roofs of both the himulayan and lulapong are thatched with cogon grass. The roof of the lulapong is a gable that falls down to the level of the floor, thus giving the whole structure a pyramidal look (Quimpo et al. 2003).

Today, more and more Ata Manobo are building houses in communities where Christian settlers reside, and their houses look similar to those built by the latter and may already have second or third rooms, a narrow balcony, and a separate kitchen. Galvanized iron is now used as roofing material and wooden slats used for floor and walls. These are evidence of the improved economic conditions of Ata Manobo, but these are no doubt influenced by the Christian settlers.

Ata Manobo Clothing, Tribal Attire and Costume

The color scheme of the Ata Manobo’s traditional finery and jewelry is very similar to those of the Bagobo, the Mansaka, and the Tiruray. Common colors used are blue and red, with occasional streaks of yellow and black.

The men don long-sleeved shirts called pinuta and semi-loose shorts called bandera. There are three kinds of headgear, worn depending on rank. The tangkolo is used by the apo, igbujag no datu, and bagani. It covers the entire head and is heavily sequined or beaded, with horse or goat hair worked into the sides. The sinolaman, used by hibatoon no datu, is similar in shape to the tangkolo and is wrapped around the head; however, it does not cover the pate. Longkos are much simpler and cover only the sides of the head; these are used by ordinary Ata Manobo.

The datu may wear multilayered balukag (necklaces) to signify his rank. His tribal finery includes a sinagibulan (sun-shaped bronze container), which contains mama ingredients; an ilab (short, curved knife) used for slicing bunga nut; a lipit (bronze metal chain belt); a tongkaling (heavy bronze belt); and a s’ning (heavily beaded shoulder bag). The datu or biyo’s alternative container for betel chew ingredients is the binukag (a beaded shoulder bag).

The attire of a typical Ata Manobo woman consists of the ompak (red, short blouse with striped patterns); a patadyong for a skirt; occasionally a malong; a palakot (red cloth belt), and a single strand of multicolored bead necklace. The ompak is sewn with bias tapes of different colors, usually white, yellow, and red, arranged into squares, with minimal use of sequins or beads.

|

| Ata Manobo from Talaingod in their native attire, Davao del Norte (Photo courtesy of the Office of Senator Loren Legarda) |

Jewelry is worn to signify rank. The biyo or female baylan wears several strands of baliog / balyog or banda (beaded necklaces) and buday (bracelets) to indicate authority. Ear ornaments can be as ornate as one’s family’s wealth allows: A woman may wear simple aritos (beaded earrings) or the more elaborate sungol (beaded ornaments that hang from ear to ear) that fall just below the chin. The women have two types of decorative combs for their hair: the arang (bamboo comb) and the sugkad (comb decorated with multicolored colorful threads of yarn). The Ata Manobo may also wear a variety of anklets: Tikos are made with beads, while sinibod are made of agsam vinesor uway seeds.

Traditional materials used by the Matigsalug to create their adornments are shells, seeds, wood, metal, and trade beads such as carnelian and coral beads known as balieg— tiny, multicolored beads woven using fiber and hair. There are many different types of necklaces with varying designs such as the behek,a half-inch wide flat woven necklace with many patterns and batikmotifs. There are also the salapid and the lembeng, both wide, beaded waist belts.

Pangutob or pangateb (tattooing) is one of the most sacred practices of the Ata Manobo. Among the Matigsalug, the design is incised on the skin with a gupes (knife) and inked with soot from the burned wood of the salumayag tree. The men have images of lizards or alligators tattooed on the inner part of their forearm or their posterior leg. The women have three lines circling their abdomen and lumbar area. The reverse is more common among the Matigsalug: Parallel lines are drawn around the forearms and geometric designs around the waist. Some believe that after death, the black soot will light up and help guide the soul on its journey to the otherworld. Some women display five-inch wide tattoos on their bellies, visible between their ompak and patadyong. These can be purely decorative or may be an expression of a woman’s pride in her identity as a member of an indigenous group. On the other hand, it is taboo for the Matigsalug to boast of their tattoo as a trophy, or else the deities may take away its efficacy.

Ata Manobo Weaving and Handicrafts

|

| Talaingod basket or leban made of bagtok and rattan (Photo courtesy of the Office of Senator Loren Legarda) |

Pangimo is the Matigsalug practice of weaving or plaiting without a loom. Common materials used are abaca, buri, palm leaves, rattan, and agsam vines. Some products created out of pangimo are liyang, a basket typically carried by wearing the sinalapid (woven band) attached to the mouth of the basket and strapped around the upper forehead so that the basket hangs at the back of the head; bokag, a large carrying basket; binebey, the smaller version of the liyang; sinakeb, an even smaller version of the binebey; leban, a tall, round container basket; tahakan, a traditional measuring tool about the size of a mug, used for rice and corn grains; nego, a winnower used to separate the tahop (rise husk) from the clean grain; bubo, a trap made of woven bamboo sticks used to catch fish in the river; and binukol or tikes, woven bangles, bracelets, and armbands. Other Ata Manobo woven products are the ginuboy, a small basket used for keeping accessories; the takudyan, a basket made from bagtok, used for storing rice; and the opi, a basket bag made from uway, especially used for keeping captured native chickens (Burton 2014; Abarca 2014, 10).

|

| Talaingod basket or liyang made of bagtok and rattan (Photo courtesy of the Office of Senator Loren Legarda) |

|

| Talaingod basket or ginoboy made of bagtok and rattan (Photo courtesy of the Office of Senator Loren Legarda) |

Pangabel is the process of weaving fibers, such as abaca hemp and cotton on the habelan (backstrap loom). However, cultural erosion through the years has caused these traditional weaving practices to disappear. Only a few older women living in remote communities still possess the traditional knowledge of cotton weaving.

The Matigsalug have a tradition of woodcarving called pangopit or panapsap. Different kinds of wood like banati, balayong, and lawaan are carved with designs based on creatures and objects in their immediate environment or on stories told by community elders, and made into handles for special ceremonial blades.

Ata Manobo Metal Casting

Panuwang or metal casting is a tedious and sacred craft. The artisan uses taro (wax) to form or shape the product by attaching the beeswax extension as an inlet for the molten metal. Metals such as aluminum, tin, silver, copper, and bits of gold dust are melted in an angesan, a Malay forge, to make alloys. These can be shaped into adornments and decorative items like bwadey, a solid metal bracelet; sising (rings); babat, a hollow brass anklet with tiny metal bells; sandag (bracelets); and saliyew (hawk bells) (Burton 2014).

Panayab is the traditional Matigsalug blacksmithing tradition, although the practice has been largely neglected because of the increased availability of cheaper mass-produced tools in the market. Panayab is done on the angesan, with iron material obtained from neighboring communities (Burton 2014).

Various knives are used for household activities and farming. The ogpit is the basic working knife, used for clearing fields, building houses, carving wood, conducting panubad, or engaging in magahat / maghat (warfare). A variation of the ogpit is the square-tipped kampit, used by women for weeding. The ilab is small and crescent-shaped, used for woodcarving and cutting betel nut; the smaller gupes and forked sinawingan are used for tattooing. Wasey (axes) are of two kinds: lantuy for cutting deep into the trunk, and perikel for wielding like a lumberjack axe (Burton 2014).

Other knives are used for ceremonies or other special occasions, like the the manangkabaw, a ceremonial war knife; the kampilan,which resembles a Maguindanaon knife; the esiro, a long knife curved like a crescent moon; the sinangyaw, a long knife that curves upward like a kampilan, with a square or forked tip; the lambitan, a knife that looks like the sinangyaw but does not have a forked tip; the porok, the biggest of all Matigsalug knives, used to chop or bash through wooden shields and armors; and the balarew, a double-edged knife with the tip protruding at the end of the pommel.

The Ata Manobo’s tunod (bow and arrow) are of three kinds: the salupit, which has three arrow tips and is used for hunting birds and monkeys; the ambukang, which has two arrow tips and is used for targeting birds or persons; and the busog, which has only one arrow tip and is used for targeting persons.

The bangkew (spear) consists of an iron point mounted on a tampakan (shaft) made of bahi palm. There are five kinds of spears: the boriyak, the limbas, the kalawet, the binangkow and the pojos. The boriyak, limbas, and binangkow are used by the bagani during pangayaw. The boriyak, kalawet, and limbas have pointed anahaw tips, while the binangkow has a pointed metal tip. The kalawet is used for hunting deer, monkey, and wild pigs. The pojos is used for hunting and pangayaw, as well as a cane for old men. Its pointed tip is made of anahaw and it has a much shorter handle than the other spears.

The Matigsalug use the binaley, a short spear, for hunting, warfare, and rituals; kummag, a “house spear” that is placed near the door of the home, for protection against evil; deldeg, a long spear for hunting and babale (divination); kalawit, a harpoonwith a detachable head strung to the shaft, for hunting deer and boar; and the sacred sinipit, an ornate spear used for large rituals or as gifts during peace settlements and payments for indemnity.

Ata Manobo Riddles

The recitation of antokon (riddles) is a popular activity among the Ata Manobo. Riddles describe things in the environment of the community or refer to their deities, attesting to the richness of imagination and wealth of lore of the Ata Manobo. The following are some examples:

Dolyan ni Moibulan darowa no sugpang napuno tu

bogas. (silo-silo)

(The durian tree of Moibulan has two branches,

laden with fruit. [weeds])

Owol ko maalow lanao ko marosilim. (ikam)

(Snake at daytime, sea at night. [mat])

Bawobato no magaso ug pukootol kog susunob no

ug kitoon taro ka gusok. (pukot)

(A thin young man is a good fisherman when diving

in the sea. [fishnet])

Ug pamagoloy kag hun-a; ug pamonhit ka mohuri.

(lumansad)

(The first hunted with bows and arrows; the last one

fished. [rooster])

Daga nog kaburos, no marasig ka habot. (aguloy)

(Young maiden when pregnant uses many malong.

[corn])

Ata Manobo Stories, Myths & Legends

All Manobo groups share the epic Ulaging, also known as Uwaging or Ulahing, which tells of the exodus of their ancestors. Genealogically, the Ata Manobo trace their descent to Banlak, the brother of the Talaandig epic hero, Agyu (Industan 1992, 4).

“Ka Sugilanon ni Banlak” (The Story of Banlak) tells of a Pulanguihon high priest who preached during the time of a long dry spell. Upon the mandate of his guardian spirit, Banlak tells the people to construct a boat because a great flood is coming. But the people laugh at him because the current drought makes his pronouncements seem unlikely. His brother-in-law, Boybayan, also tries to convince people. No one listens.

|

| Giant under the sea with Banlak and his sister (Illustration by Benedict Reyna) |

After twelve years of drought, the people are surprised when heavy rains suddenly begin to fall. For forty months, forty days, and forty nights, the deluge rages and submerges everything but the mountaintops. To sustain the people, Banlak places a mound of earth near the prow of the boat, where he plants a kawot blessed by a bantoy. Every morning, he uproots and cooks the kawot, then plants it again so that it grows back in time for lunch, and again in time for dinner.

|

| Banlak constructing a boat (Illustration by Benedict Reyna) |

When the flood subsides, there are only a few men left with Banlak, and they find themselves at the mouth of the Kapalong River. The men who had not believed in Banlak congregate around him. He tells them to live righteously, as he will soon pass into the afterlife. Banlak proceeds to the sea as his brother-in-law, Boybayan, takes to the skies. When Banlak reaches Liwanon at the bottom of the sea, a giant blocks their path and demands to marry his sister Boyenan before they can be granted passage. After Banlak agrees, he proceeds to Liwanon, the place where there is no death.

Various parts of “Ka Sugilanon ni Banlak” tell of the origins of names and places that the Ata Manobo occupy. For example, the river Malibuganon derived its name from the weeds that sprouted up on the dried-up riverbed during the long drought. The sitio called Mangutkot, meaning “dug up,” got its name from the time that Banlak’s dog heard the sound of water rushing beneath the ground and dug up the earth to allow the water to flow.

The Ata Manobo have stories of other characters from the Ulaging epic. There are the tales of Tulalang who was constantly pursued by the Ikogan (tailed men) all over Mindanao. This explains why there are so many stories of Tulalang all over Mindanao. Tulalang managed to defeat all the Ikogan in Ginubatan (Battlefield), where he stayed until he ascended to heaven without passing through death. After Magbabaya took Tulalang, he left a couple in charge to replace Tulalang; the couple produced children to create the different tribes of Mindanao.

|

| Tulalang pursued by Ikogan or tailed men (Illustration by Benedict Reyna) |

The Talaingod have a story of how Tulalang fought Kalamkalam, a powerful being who was leveling the mountains of Mindanao. Kalamkalam’s power came from the saldawan bird while Tulalang’s came from Magbabaya; thus, Tulalang was able to soundly defeat Kalamkalam. Tulalang is said to be the creator of a mysterious spring of water on a hill to supply people during a drought; the spring slows to a trickle during the rainy season but gushes strongly during a drought. To date, the people still take great care of Tulalang’s water.

The Matigsalug have their Tulalang stories as well. In one narrative, Tulalang is told by his abyan to kill all who have committed wrongdoing, including his own cousin, Mangintalunan. After meting out this mandate, Tulalang sees that there are no more people left. He chews on some buyo given to him by his abyan and spits on all the dead to bring them back to life. Later stories of Tulalang reveal his continued significance in the Manobo worldview in spite of the influx of colonizers. In one story, Tulalang is proven as the greatest bagani when his mark, a metal bar, floats on the waters of the Malarugaw River while an American challenger’s mark, salapi (money coin), sinks to the bottom.

Another Ata Manobo hero is Agyu. In one story, Agyu is suffering from a disease called ibong, which has covered him with sores and has driven everyone away from him, including his family and wife. Instead, they ask Ulanas, his nephew, to bring him food. One day, Agyu bids Ulanas to kill a deer and bring it to him. The boy slaughters the deer and is surprised to find cooked rice inside. Agyu tells him to cut out the heart and liver and serve them to his family. Once Ulanas removes the heart, liver, and intestines, the deer comes back to life and returns to the woods. The family refuses Agyu’s gifts because they fear that the deer’s heart and liver may be contaminated by Agyu’s disease. Chagrined, Agyu takes the pot and beats it as a drum. The sun rises and a sarimbar (boat) arrives. The sarimbar travels to Sinayawan, Ginubatan, Salog, and Salangan, taking with it 10 worthy people as it goes. Only Agyu’s followers can board the sarimbar; those who oppose him cannot come aboard. The sarimbar hangs over Calinan as those left behind are slaughtered by Ikogan or turned into monkeys.

The Ata Manobo have a variety of creation myths. According to one version narrated by the baylan Libuangan Lapindoy, in the beginning, there was nothing but space filled with clouds and mist. Out of these mists emerged three bright things: Manama, Tahabikal, and Mandalangan. Manama, also called Monsuman wuy Binakolan (chief and creator), decided to create the world, beginning with a magnet that formed the foundation to keep the world from falling apart. Next, he created the pangngirakon, a prison for those who disobey him, and the dahat tu lihawwasan, a paradise, not of heaven but of the world, for those who follow him. He created the pahalungan, a place where four posts hold up the heavens, and from the same material, the sun, moon, and stars. He created the soil and covered the world with it; out of what is left, he created the first man, Addan, and, out of his rib, the first woman, Ebba. The center of the world that Manama created was Mindanao, but Addan and Ebba’s children soon went on an exodus to America, Mica, Saudi Arabia, Luzon, and Visayas, begetting generation after generation of children in these places.

For the Matigsalug, Agyu is the creator of the first man, Wali, and the first woman, Ilangkan. They gave birth to seven boys and seven girls who later propagated and populated the races of the world.

In a different version of the origin narrative, Manama wove eight men, the ancestors of the Ata Manobo, out of blades of grass. However, a great flood carried them away and they would have perished had they not been aided and brought home by an eagle (Tiu 2005, 242).

Ata Manobo folktales reflect their cultural values, customs, and traditions. Social institutions such as governance, marriage, and family relationships are depicted in these tales.

The “Sugilonon bahin ki Lungpigan” (Story of Lungpigan) tells of a boy who has an altercation with a King, who had purposely stepped on Lungpigan’s kite while he was playing. Angered when the boy tells him that he is ill-mannered, the King tries to get back at Lungpigan by challenging him to make a male horse pregnant. Lungpigan chastises the King and tells him to do good instead. The King is impressed and offers Lungpigan his daughter’s hand in marriage. Lungpigan marries the princess and later succeeds the King to the throne.

“Ka Balo no Duon Anak no Usa” (The Widow with a Deer-Child) narrates the story of a woman whose husband dies before she gives birth to a deer-child. The mother laments that she cannot eat rice because there is no man to clear the field for her to plant in. Thus, the deer-child decides to go on a journey to secure rice and better food. After many rejections by rice farmers, it comes upon a hut where a brother and sister receive it warmly. During the harvest, the siblings find out that the deer-child has magical abilities to carry large quantities of rice in its body. One day, the young man finds out that the deer-child is actually a beautiful young woman in a deer disguise. He steals her disguise and hides it away. When he admits what he has done, the mother tells her daughter that she must marry the young man so as not to be shamed.

“Bujag nu Pataanak tu Daga ” (The Old Woman and Her Daughter) tells of an old woman who lives alone with her daughter. Because of this, the daughter carries out the roles of a man and hunts for food for herself and her mother. One day, a young man becomes interested in her even as she tries to fend him off to avoid shaming herself. The young man, with his sister, makes a visit to the old woman and her daughter, offering to take them with him to his home so that they no longer have to live alone. The old woman bids her daughter not to refuse him. Fetched from her house to the man’s abode, the girl has no choice but to love and marry him.

“Dagan a Maghahabol” (The Lady Weaver) is a story of a woman who one day receives a strange omen through an alimukon. The omen comes to fruition when, after fetching water from a well, she returns home to find a man sobbing by her loom and asking her for a piglet. She makes excuses to leave the house and tells her comb and water container to fend him off so that she can run away. The man then turns into a night creature and starts to chase after her. The woman tries to get help from various forest creatures to escape, but to no avail. Finally, she comes upon a young man who falls in love with her and begs her not to run off. He kills the night creature easily with a magical bow and arrow. The woman feels suspicious of the man’s intentions and he eventually confesses that he had been the one who set the events in motion so that she would marry him. Despite her better judgment, she consents to marry him.

The Ata Manobo have stories of a trickster named Datu Kulukog, who tends to show up in stories about outside forces that bring peril to their society. In one story, the Americans arrive supposedly to preach good news; they build a house and invite people to come and leave behind all their belongings. Kulukog’s abyan, the kakkak (guardian spirit), tells him to dig a hole because a calamity is coming. When everyone is inside, the Americans spray poisonous smoke into the house, killing everyone inside except Kulukog, who escapes on the advice of his guardian spirit. In another story, the Ikogan are conducting military operations that result in numberless killings. To retaliate, Wulo tricks the Ikogan by baiting them with fake news of Datu Kulukog, whom the Ikogan are seeking. Wulo tricks them into the dangerous parts of the river where the currents are strong. All the Ikogan, except for one woman, are carried off and fall into the waterfalls to their death.

Ata Manobo Songs, Dances and Rituals

Songs, dances, and rituals are important aspects of the lives of many indigenous peoples. The Ata Manobo, too, have many opad (songs). Some are meant to be sung during the day, such as the inongajon, panig-ab, indakol, palondag, and babayako, while others are meant to be sung at night, such as the tud-om and sugilon. The Ulaging may be sung anytime by anyone in the community.

|

| Ata Manobo couple playing a bamboo zither, left, and a two-stringed lute, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

The limbay is a lullaby sung by mothers to put babies to sleep. The ingkakak is a song sung to entertain children. It is about a funny man who is always bitten by vermin, animals, and insects wherever he goes. Because he cannot fight them, he simply resigns himself to letting all these bothersome elements bite him. Another song for children is the ololok, about a hunter named Ololok who hunts a pig through the forest. He ties the pig to carry it on his back, but the vine that he uses does not serve him well, and the pig keeps falling. Finally, he simply uses his hair to tie the pig in place. The ugongan is an improvised song based on current events or happenings. It may also be used to court a girl.

The musical instruments of the Ata Manobo are similar to those of other lumad groups in Mindanao. Percussive instruments include the agong, the gimbal, the tagotong, and the bangkakaw. The agong or gong is the most common, coming in variable sizes and used mainly to provide rhythm to a dance or to accompany other instruments. The gimbal is a drum with a round body made of bahi, a kind of hardy palm tree, and with the top and bottom covered with dried deerskin or goatskin. The tagotong is a meter’s length of hollowed-out bamboo, beaten with sticks to provide rhythmic sounds. The bangkakaw, which is now rare, is a hollowed-out tree trunk placed upside down and struck by one or two pestles called ando to produce sound to accompany a lumad dance.

The Ata Manobo also have a variety of string instruments. The kudlong is a two-foot stretch of bamboo with six thin strings carved out of the bark of the same bamboo. The sawroy / saluroy is a guitarlike musical instrument with two strings, much like a takumbo, except that the takumbo is made of bamboo. Ata Manobo also use a kagot, a violinlike instrument with strings made of abaca fiber.

Wind instruments are used for celebrations, dances, and community gatherings. The sagoysoy (small flute) and the pwondag (big flute) are played at many assemblies and events. The kubing is a popular instrument for accompaniment. It is a small, thin, bamboo slat that is pointed at one end. It is played by blowing controlled wind through the player’s mouth over a slit in the middle of the slat, while the player gently taps at one end to produce varying sounds.

|

| Talaingod ensemble, with drum and agung (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

Ata Manobo dances build on basic steps and movements: The hag-ot is a pulling or heaving movement; banloy is the swaying of the hips; kuddol is the bending of the knees; and takurang, which is the stamping of feet, imitates the grinding of rice and corn.

The aabaka, bangkakow, and inamungan are occupational dances that mimic community members at work. The bangkakow, also called a log dance, is danced to ask for Manama’s blessing during harvest. It is performed by four females in a rhythmic, circular dance motion while two males tap at the bangkakow with pestles. Aabaka is a dance that imitates the pulling out of the abaca trunk, a move called hag-ot, and is typically performed during the harvesting of abaca. A variant is the abakahan, performed by both men and women whose movements imitate the stripping of fiber from the abaca plant. The pupolod is danced before a tree-felling activity, and the inamungan is a harvest dance performed during the rice harvest season.

The bangkakawan or bangkakaw was originally conducted during fishing activities. The log instrument used is made from the hollow trunk of a tree, which is suspended between two poles with rattan strips. Wooden sticks are used to pound on the log and create a beat. To the sound of the bangkakaw,men and women dance while mimicking the fish swimming in the water, while others imitate the gestures of trying to catch or spear the fish.

Ritual dances performed by the baylan are the gimukudan, to revive or reawaken the gimukodor soul of one who has died, and the binaylan, to call upon a deity. The pungko is a dance depicting a person with a disability, performed to ask for Manama’s miraculous healing. Saot is a war dance offered to the deity Mandalangan. The natarin is performed to express grief and mourning because someone has passed away or something has been lost.

Social gatherings are occasions for boisterous, sometimes humorous, communal dances. The kalasag is a war dance performed by two male dancers, depicting a fight scene using a bangkaw or tabalo (arrow) and kalasag (shield). The tagudturan is a dance performed to a fast beat by one female and one male dancer. The Ata Manobo’s courtship dance, the pulutawi, imitates the movement of birds as they fly, hop, and mate with each other. Dances imitating creatures in the environment are the pangobal (monkey dance) and the binakbak (frog dance).

The Ata Manobo regularly commune with the deities through prayer-rituals conducted by the baylan or the datu of the community through the panubad or pangapog. Poghinang is a thanksgiving rite for significant occasions such as pogharay (rice harvest), sunggod to kamanga (swidden rites), and ogkalomidka mongo suwod (family or clan reunions). It is usually a festive, two-day ritual. On the first day, a slightly raised platform called dogbahan with a makeshift altar called angkow is constructed and decorated with young buds of the coconut and carvings. The dancing of the baylan, possessed by a bantoy, begins the ceremony. On the second day, a pig is placed on the dogbahanas an offering to the deities. Later, the pig is cooked, along with other prayer-offerings, in a huge feast.

In pre-swidden rites, seeds, seedlings, and other farming implements are placed at the center of the kaingin area, prayed over, and offered to the gods. A chicken or pig is also slaughtered in the center of the clearing, its blood smeared on the four corners of the kaingin.

A pogpongapog is a prayer-ritual for good harvest, good health, or thanksgiving. Among the Ata Manobo, harvesting is done as a community in the tradition of parula or bayanihan. Before the harvest starts, the baylan offers broiled chicken to the deities in thanksgiving. The first grains or cobs are also usually given as prayer offerings in a haray (thanksgiving ritual).

A panubad is undertaken by bagani before a pangayaw. The baylan invokes the guidance of the deity Mandalangan to grant them courage and success in their endeavor. The bagani then drink the fresh blood of a slaughtered chicken or pig, or eats the animal’s liver, because they believe it infuses them with the boldness and fierceness of the blood spirit tagbusaw.

Pangujab is performed on a person with an illness. The baylan invokes Manama or Magbubuot for healing while sweeping a slaughtered chicken, its wings spread out, over the head of the patient and around the patient’s body. This may also be performed to prevent sickness, to drive away evil spirits, or to ensure good luck and the endowment of blessings.

Pogsusugoy is a ritual before the hunter goes on an expedition. An egg and three slices of betel nut, along with some condiments for mama or betel chew, are placed on a small plate and offered to the deities Solokon and Talabobong in the yard in front of the hunter’s hut. Buyo leaves are placed on the stairs or by the door of the house to ward off the negative energies. The objects are removed only after the first catch has been trapped or three days after the hunter returns without any game.

During the installation of a new datu, the baylan starts the rites through the prayer-offering of a pig, betel nuts, and mamaon (bowkan leaves) to the deity Tagonliyag. The new igbujag no datu formally announces his assumption of leadership by donning the tangkolo, the headdress that symbolizes the datu’s authority. Datus from neighboring communities grace the occasion and offer blessings and inspiring speeches to the new datu, after which there is singing and dancing, and the bagani performs the war dance. The whole affair ends with a sumptuous feast.

The Ata Manobo as Featured in Films and Media

Mindanao filmmaker Hugh Montero has produced two films depicting the struggle of the lumad to defend their right to education. Pahiyum ni Boye (Boye’s Smile), 2014, follows the story of a Manobo girl whose poverty forces her to drop out of school. Subsequently, the lumad community works to build its own school. Pakot (Wild Boar), 2015, a continuation of Pahiyum, is the story of a non-lumad schoolteacher who dedicates her life to teaching children in the hinterlands. It won Best Film in the 11th Mindanao Film Festival.

Habi Arts: Habi ng Kalinangan produced Pangandoy: The Manobo Fight for Land, Education, and Their Future, 2015, a short film by Hiyas Saturay, covering the indigenous peoples’ struggle for land and education during the filmmaker’s three-month stay in Mindanao and immersion in Talaingod communities.

GMA Network Davao covered the Talaingod exodus in a short documentary titled “Lipunon te Talaingod,” 2015, for the program Isyu Mindanao, written and reported by John Paul S. Seniel.

Kilab Multimedia, an online-based alternative media outfit, focuses on political issues in Mindanao. It has produced short documentaries about the Talaingod’s plight, such as Defend Talaingod: The Lumads’ Quest for Justice (2014). As a media team, Kilab followed the caravan of lumad evacuees from Mindanao to Manila in the Manilakbayan 2015. One of their videos on YouTube is a feature of the woman chieftain Bai Bibiyaon Ligkayan Bigkay, who railed against North Cotabato Congresswoman Nancy Catamco for attempting to have the lumad evacuees evicted from their evacuation camp in UCCP Haran in Davao City. The outraged chieftain called out Catamco for breaking her word and reminded Catamco of their exchange of gifts when the congresswoman gave the Manobo children schoolbags and she, in turn, gave a gift of beaded necklaces. She calls for the disarming of the paramilitary group Alamara, whose activities have prevented them from returning to their homeland.

|

| Kilab Multimedia’s Defend Talaingod: The Lumad’s Quest for Justice, a short documentary on the Talaingod’s plight, 2014 (Kilab Multimedia) |

Talaingod kudlong players and the fierce Bae Bibiyaon Bigkay have collaborated with various artists like Gary Granada, Bayang Barrios, Cookie Chua, Lolita Carbon, Brownman Revival, and Gloc-9, for the music video, “Mindanaw,” 2015, directed by King Catoy. “Salupongan,” 2016, directed by Carlitos Siguion-Reyna, is a collaboration of over a hundred artists and musical groups, such as John Arcilla, Aiza Seguerra, Isay Alvarez, Robert Seña, Mae Paner, Christopher de Leon, Edgar Mortiz, Bimbo Cerrudo, Cris Villonco, Lorenz Martinez, Myke Salomon, Baihana, Patatag, UP Cherubim and Seraphim, and Coro de Sta. Cecilia. Both songs are gestures of solidarity with the lumad in their struggle for land and for just and lasting peace.

Sources:

- Abarca, Jezreel. 2013. “A Documentation of the Ata-Manobo Dances in Talaingod, Davao del Norte.” Southeast Asian Interdisciplinary Research Journal 1 (2): 1-18. http://www.brokenshire.edu.ph/bcjournal/index.php/sair/article/view/27.

- Apas, Nestor (Datu). 2013. Interviewed by Rolando Bajo, Maminturan Foundation, Tagum City, Davao del Norte, 11 December.

- Arkibong Bayan. 2014. “Struggle of the Talaingod Manobos in the Pantaron Range: Defending Their Land against Mining and Logging Companies amidst Aerial Bombings and Other Human Rights Violations by the Philippine Military.” Arkibong Bayan, 18 May. http://www.arkibongbayan.org/2014/2014-5May18-Talaingod/Talaingod.htm.

- Bajo, Rolando. 2004. The Ata-Manobo: At the Crossroads of Tradition and Modernization. Davao City: Holy Cross Press.

- Bat-ao, Durung. 1977. “Sugilon Bahin ki Lungpigan.” Studies in Philippine Linguistics 2 (2): 91-99. Casilda Edrial-Luzares and Austin Hale, series eds. http://www-01.sil.org/asia/Philippines/sipl/SIPL_2-2_091-099.pdf.

- Burton, Erlinda M., and Jay Alovera. 2009. “Revival of Cotton Weaving among the Matigsalug Manobo of Kalagangan, San Fernando, Bukidnon.” Kinaadman Research Center, Xavier University. Unpublished manuscript.

- Burton, Erlinda M., Moctar Matuan, Guimba Poingan, and Jay Rey G. Alovera. 2006. “Choices of Response to Inter-kin Group Conflicts in Northern Mindanao (section on ethnography).” Research Institute for Mindanao Culture Papers, Xavier University, Cagayan de Oro City.

- ------. 2014. “Matigsalug.”Unpublished manuscript. Wordfile.

- Catoy, King, director. Mindanaw. YouTube video, 7:29 minutes, posted by Salugpongan International, 11 December 2015. https://youtu.be/FjxB9sWxO3Q.

- Cole, Fay-Cooper. 1913. The Wild Tribes of Davao District, Mindanao.Project Gutenberg, 2006.http://www.gutenberg.org/files/18273/18273-h/18273-h.htm.

- Corcino, Ernesto I. 1988. Davao History. Philippine Centennial Movement, Davao Chapter

- Dacayanan, Liza. 2014. Interviewed by Dr. Rolando Bajo, Kapalong Tribal Office, Kapalong, Davao Del Norte, 28 January.

- Davao, Arturo. 2013-4. Interviewed by Dr. Rolando Bajo, Municipal Tribal Chieftain’s office, Kapalong, Davao del Norte, 17 October 2013; 18 February 2014.

- Davao, Marcela. 2014. Interviewed by Dr. Rolando Bajo, Kapalong Tribal Office, Kapalong, Davao Del Norte, 18 February.

- Davao, Marilou. 2014. Interviewed by Dr. Rolando Bajo, Kapalong Tribal Office, Kapalong, Davao Del Norte, 28 January.

- Defend Talaingod: The Lumads’ Quest for Justice. YouTube video, 10:27 minutes, posted by Kilab Multimedia 7 April 2014. https://youtube/3gfr5PyTKHM.

- Demetrio, Fransisco, SJ. 1978. Myths and Symbols: Philippines. Manila: National Bookstore for Xavier University.

- Eugenio, Damiana. 1989. The Folktales. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Folklorists Inc.

- ———. 1994. Philippine Folklore Literature: The Riddles 5. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- ———. 2002. Philippine Folk Literature: The Legends. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- Face to Face: Woman Chieftain Slams Catamco a Traitor. YouTube video, 5:09 minutes, posted by Kilab Multimedia, 26 July 2015. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lnKKp-SpFWk.

- Gloria, Heidi K., and Fe R. Magpayo. 1967. Kaingin. Davao City: Ateneo de Davao University Press.

- Gollas, Noria. 2014. Interviewed by Dr. Rolando Bajo, Kapalong Tribal Office, Kapalong, Davao Del Norte, 28 January.

- Hart, Donn. 1964. Riddles in Filipino Folklore: An Anthropological Analysis. New York: Syracuse University Press.

- Horfilla, Nestor, ed. 1996. Arakan: Where Rivers Speak of the Manobos Living Dreams. Davao City: Kaliwat Theatre Collective.

- Inansugan, Lario. 2013. Interviewed by Dr. Rolando Bajo, Municipal Tribal Chieftain’s office, Kapalong, Davao del Norte, 17 October.

- Industan, Edmund Melig. 1992. “The Family among the Ata Manobo of Davao Del Norte.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 20 (1): 3-13. http://www.jstor.org/ stable/29792071.

- ———. 1993. “Detribalization of the Ata Manobo: A Study of Ethnicity and Change.” PhD dissertation, Xavier University – Cagayan de Oro City.

- KAMP (Kalipunan ng mga Katutubong Mamamayan ng Pilipinas). 2012. “The Human Rights Situation of the Indigenous Peoples in the Philippines.” United Nations Human Rights, Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights. http://lib.ohchr.org/HRBodies/UPR/Documents/session13/PH/KAMP_UPR_PHL_S13_2012_KalipunanngmgaKatutubongMamamayanngPilipinas_E.pdf.