The Bicolano People or the Bikolanos (Bikol: Mga Bikolnon) History, Culture and Traditions [Bicol Region Philippines]

Bikol and Bikolnon both refer to the people, culture, and language of the Bicol region. The term “Bikol” could have been derived from “Bico,” the name of a river that drains into San Miguel Bay. Possible origins also include the bikul or bikal bamboo trees, which line rivulets, and the ancient native word bikod (twisted or bent).

Administratively known as Region V, the Bicol region is located on the southeastern end of Luzon. It is surrounded by the Visayan Sea in the south, the Pacific Ocean in the east, Lamon Bay in the north, and Sibugan Sea and Quezon province in the west. It comprises six provinces: Camarines Norte, Camarines Sur, Catanduanes, Albay, Sorsogon, and Masbate.

Bicol has a rugged topography. Its highlands tower over the few expanses of plain, which are concentrated in Camarines Sur and Albay. These include Mayon Volcano, Mount Malinao, and Mount Masaraga in Albay; Mount Isarog, Mount Iriga, and the Calinigan mountain range in Camarines Sur; and Bulusan Volcano in Sorsogon. Important bodies of water are Lamon Bay and San Miguel Bay; the Lagonoy, Ragay, Albay, and Asian Gulf; the Sibugon Sea, Burias Pass, Ticao Pass, and Maqueda Channel; and the freshwater lakes of Buhi, Bato, and Baao in Camarines Sur and Bulusan Lake in Sorsogon. Rains fall regularly and heavily over the region; precipitation generally exceeds 2 meters annually, with Baras in Catanduanes receiving 5.4 meters of rain annually—the highest in the country. Frequent and destructive typhoons mark the later months of the year.

In 2010, the regional population stood at 5,420,411, spread out over a land area of 17,632.50 sq km. However, the Bikol people are widely dispersed outside the Bicol region. As of 2000, they make up the largest non-Tagalog group in the following cities of Metro Manila or the National Capitol Region: Caloocan City, 59,276 or 5.05% of the city’s population; Pasig City, 24,678 or 4.9%; and Valenzuela City, 21,896 or 4.55%. In Quezon City, they rank second in population size after the Bisaya, numbering 108,293 or 5%. In Manila they number 39,295 or 2.5%, ranking third, after the Ilocano and Cebuano. They are the largest non-Tagalog group in the following provinces of Luzon: Rizal, 73,253 or 4.30%; Laguna 57,282 or 3%; and Batangas 11,661 or 0.42%. They rank second after the Bisaya in the following provinces: Cavite, 52,031 or 2.54%, Bulacan 43,605 or 1.95%, and Quezon, 36,339 or 2.45%. They are found as well in the following provinces: Aurora, 7,079; Pampanga 6,685; Oriental Mindoro, 2,930; Cebu 1,534, which is 0.06% of the population; and 247 in Marinduque. In just this random survey, the Bikol people make up a total of 545,544 or more than half a million, residing outside their region of origin. On the other hand, other ethnolinguistic groups in the Bicol region, besides the Tagalog, are the Bisayans, particularly the Cebuano and Ilonggo; and the Kankanaey from northern Luzon.

The Bicol region has at least eight Bikol languages: Buhi’non Bikol, Central Bikol, Libon Bikol, Miraya Bikol, Northern Catanduanes Bikol, Rinconada Bikol, Southern Catanduanes Bikol, and West Albay Bikol. These further include at least 11 dialects. The Bikol that is spoken in Naga, Albay is generally considered to be Standard Bikol. The number of households in Metro Manila that speak Bikol is 11,689, thus comprising the third largest non-Tagalog-speaking group in Metro Manila, after Ilocano and Bisaya.

History of the Bicol Region

The Bicol region was known as Ibalon, variously interpreted to derive from ibalio, meaning “to bring to the other side,” or ibalon, “people from the other side” or “people who are hospitable and give visitors gifts to bring home.” It might also be a corruption of Gibalong, now a sitio of Barangay San Isidro, Sorsogon, where the Spaniards first landed in 1569. The Bico River was first mentioned in Spanish documents in 1572. The region was also called “Los Camarines,” after the huts found by the Spaniards in Camalig, Albay.

|

| Cagsawa Church ruins in Daraga, Albay with Mayon Volcano in the background, 2011 (Christian Bederico) |

No prehistoric animal fossils have been discovered in Bicol, and the peopling of the region remains obscure. The presence of the Aeta from Camarines Sur to Sorsogon strongly suggests that aborigines lived there long ago, but the earliest evidence is of middle to late neolithic life.

Ancient artifacts have been discovered in several areas of Bicol: stone tools and burial jars in Bato, Sorsogon; burial jars in Bahia, Bagatao Island in Magallanes, Sorsogon and in the Batongan Cave in Mandaon; golden crowns, believed to date from 91 BC to 79 AD, in Libmanan, Bulan, and Juban; and 14th- and 15th-century ceramic plates, clay pots, and human skeletons with bronze arm and leg bands at the Almeda property in Cagbunga, Pamplona, Camarines Sur. Excavated from the limestone hills in the Kalanay cave, Aroroy, is pottery labeled the Sa-Huynh-Kalanay complex because of its correlation to Vietnam artifacts dating between 400 to 100 BC. Other artifacts in Masbate indicate early trade relations with China. In Burias, Masbate, caves yielded pre-16th-century sealed, wooden caskets, not the hollowed-out logs commonly found elsewhere. The Ticao Stone, also discovered in Masbate Island, consists of a pair of stones on which characters from the baybayin (indigenous syllabary) are incised. Although the authenticity of the two stones has yet to be determined, these have been put on display at the National Museum in Manila.

|

| Interior of a Bikol house (Le Tour du Monde, Nouveau Journal des Voyages by Edouard Charton. Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1884.) |

The Spaniards arrived in Masbate in 1567 under Mateo del Saz and Martin de Goiti, only to come upon abandoned villages, because the natives had fled to the highlands in anticipation of their arrival. For the Spaniards, however, this was no inroad but merely a stopover to restock. It was Luis de Guzman’s military expedition in 1569 that began Bicol’s colonization. From hereon, Spanish abuse in the area, as in all the other islands, began. The natives were first oppressed by Andres de Ibarra, who reached Bicol in 1570. Their gold mines too were exploited, upon Juan de Salcedo’s discovery of these during his explorations of northern Bicol in 1571. The natives’ quick defense brought upon them the whip of conquest in the forms of property confiscation, forced labor, conscription, and loss of traditional power. Within a few months of Bishop Domingo de Salazar’s arrival in the colony in 1581, he was writing letters to King Philip II bitterly complaining about the cruelty of the tribute collector in Ibalon. Tortures inflicted upon the chieftains, who were made responsible for collecting the tributes from their people, included crucifixion and being hanged by the arms until they died.

The Augustinian missionaries Alonso Jimenez and Juan de Orta pioneered the conversion of the Bikol people, who were the first natives of Luzon to be Christianized. Pedro de Chavez founded the Spanish city of Caceres near the village of Naga. In 1578, it became a Franciscan mission and in 1595, became the capital of the bishopric. On the other hand, soldier-turned-Franciscan missionary Pedro Ferrer, who was assigned to Camalig, nearly lost his life to the natives, who resented his sudden interference in their way of life.

In 1636, the region was subdivided into Ibalon and Camarines, the former composed of Albay, Catanduanes (once part of Albay), Sorsogon, Masbate, and the Ticao and Burias islands, while the latter included towns from Camalig northwards. In 1829, Camarines split into Norte and Sur, but these were reunited in 1893 and in 1919 were formally established as provinces. Bicol would also produce the first Filipino bishop of the Catholic Church—Jorge Barlin y Imperial, 1850-1909.

The Hispanization of Bicol was seen in the introduction of religious education; the introduction in 1669 by Fray Pedro de Espallargas of a hemp-stripping machine in Sorsogon, which promoted Bicol’s abaca industry; the cooperation between the natives and the colonial government in fending off Muslim invaders; and the establishment of a shipyard for the building of Manila-Acapulco trading galleons. The biggest shipyard was the Real Astillero on the island of Bagatao at the mouth of Sorsogon Bay, a site close to Sorsogon’s timber source and the San Bernardino Strait, where ships would enter from and depart for Acapulco, Mexico. In 1849, Governor-General Claveria’s decree that the natives adopt surnames nominally erased what remained of their ties to their indigenous past.

The Bikol were described by Spanish chronicler Fray Martin de Rada as very fierce warriors. Thus, their history comprises many battles against foreign incursions. Sorsogon participated in Samar’s Sumuroy Revolt in 1649. In Camarines, minor rebellions occurred contemporaneously with the Sumuroy rebellion and during the British occupation of Manila between 1762 and 1764. The natives resisted the Spaniards mainly through armed confrontation, which included an ingenious system of alarm signals when overwhelmed by the opposition. Failing these, they retreated to the hills. Mount Isarog became the refuge of renegades, whom the Spaniards called the remontados or cimarrones. Defying an order to speak only Naga Bikol, the natives continued to use 15 different languages and dialects as an act of rebellion.

From September to December 1896, some citizens of Bicol were tried, deported, or executed on grounds of subversion. Very few of those deported to Africa returned after the change of regime. Ildefonso Moreno founded the Bikol chapter of the Katipunan, the revolutionary movement, in 1897 but their uprising failed. The tribunal de cuchillo (military court) of the province killed about 500 natives to prevent future uprisings. The governor of Albay and Sorsogon and Bicol’s church officials issued other counterrevolutionary measures. Hundreds of Bikol volunteers were shipped to Manila in 1897 to reinforce the Spanish army in Luzon. Naga’s bishop forewarned the ministers of his diocese, and the vicar-forane of Sorsogon, Father Jorge Barlin, instructed his parish priests to engage in surveillance. In 1897, 11 Bikol martyrs, three of whom were priests, were executed in Bagumbayan, also known as Luneta. However, all these failed to hold back Sorsogon’s shipyard workers from revolting in Panlatuan, Pilar, Sorsogon in 1898.

On 18 September 1898, Elias Angeles and Felix Plazo led the mutiny that ended Spanish dominion over Naga. Vicente Zardin, the last provincial governor of Ambos Camarines, signed the capitulation document. Albay’s governor, Angel de Bascaran, turned over the government to Anacleto Solano after the Spaniards surrendered to Ramon Santos on 22 September 1898. After the Spanish defeat, the Philippine revolutionary government approached the Chinese for financial support. However, the generosity of the Sorsogon Chinese had been abused by Diokno’s soldiers; hence, it was more difficult to solicit funds from them. General Jose Ignacio Paua, the only Chinese revolutionary governor, claimed that between November 1898 and October 1899, he had raised 400,000 pesos from Bicol’s Chinese community.

The role of the “frailocracy” in the first phase of the Bikol revolution is uncertain. An anti-friar movement could have resulted in the 1897 execution of the Bikol martyrs. It is equally possible that Bicol’s revolutionaries were not as anti-friar as the rebels of other regions, since most of Bicol’s parishes were under the Filipino secular clergy. The Spanish Franciscans and Vincentians were well treated when the revolution broke out in Naga, and the Franciscans willingly departed with their fellow Spaniards from Albay. However, the friars suffered persecution when the revolutionary government was turned over to masonic leaders such as Vicente Lukban and Wenceslao Viniegra; and certain revolutionary government policies pressured Antonio Guevarra and Estanislao Legaspi to take a firmer stance.

Problems of financing the revolution persisted through its second phase, the anti-American campaign. For instance, Colonel Amando Airan in Sorsogon and General Paua in Albay were not sufficiently armed. When the Philippine-American War erupted in Bicol, the troops of Colonel Felix Maronilla and Captain Policarpio Ruivivar confronted the Americans under Colonel Walter Howe in February 1890. William Kobbe landed a military expedition in Sorsogon in June of the same year to sever Aguinaldo’s links with his army there and to gain American control of the abaca industry. This was countered by Gens Vito Belarmino and Paua in Albay but not by Colonel Airan in Sorsogon. Belarmino subsequently relieved the latter of his command. In February 1900, General William Bates met fierce retaliation in Camarines. Revolutionary combat escalated under Colonels Elias Angeles and Ludovico Arejola. Later in March, Arejola, Angeles, and Colonel Bernabe Dimalibot consolidated Bicol’s guerrilla forces. These 20th-century fighters revived the use of the tirador (slingshot) and anting-anting (amulets).

To entrench themselves in the region, the Americans encouraged native collaboration. However, collaborators like Claro Muyot and Anastacio Camara of Sorsogon were condemned by the local revolutionaries for accepting American posts. The Partido Federalista formed in late 1900 would become instrumental in ending resistance, such as that of Colonel Emeterio Funes in Sorsogon. Where the rebels rejected peacemaking overtures, the Americans returned in force by burning, pillaging, and killing. In addition to conventional battle and mass arrests, many war atrocities were committed throughout the region; strategic areas such as Burias Pass and Ticao Pass were blockaded. The capture of Burias’s rebel leaders deprived the Sorsogon and Albay forces of their last main supply source in the region. Arejola capitulated on 31 March 1901 but declined the governorship offered by General William Howard Taft. In Albay, even after Belarmino and Paua’s surrender, Simeon Ola prevailed until 1903. Ola was the last Bikol general to submit to the Americans.

In April 1901, the American military government was replaced by provincial civil governments under the Philippine Commission. Bicol’s economic development helped to bring it closer to the nation’s mainstream in and around Manila. With the introduction of popular education, a new curriculum was established, although Spanish remained the medium of instruction until the 1920s.

Fifty-three American Thomasites arrived in Bicol to help implement the First Philippine Commission’s policy on public instruction in the first decade of the century. Later, they were replaced by American-educated pensionados or scholars. American government and education, however, did not immediately erase the Spanish presence in the region. But like all other provinces in the country, the Bikol were soon transformed by an American education that taught Anglo-American culture. The English language was imposed and knowledge of it became an important consideration for public and private employment. Similarly, Bicol towns and provinces adopted the local government structures imposed by the Americans.

However, problems of land ownership, originating in the Spanish colonial period, were exacerbated by American colonial policies, which required all land claims in the Philippines to submit to legal formalities, particularly the Torrens title system. Residents of an area had traditionally claimed land ownership by the simple cultivation of a parcel of land. Members of the principalia (local elite) generally owned no more than 20 hectares, while the common people, an average of three. Communal land was that which had trees and plants, the fruit of which any resident was free to take. Non-residents or outsiders who desired to avail themselves of these products were required to ask for permission from the municipal officials.

However, a shrewd individual could take advantage of the sudden shift to colonialist, legal-bureaucratic procedures. In 1890, Don Mariano P. Villanueva, a migrant from Binondo, Manila, claimed the legal title to 1,300 hectares of so-called pastos (pasture land) on San Miguel, an island lying across the sea from Tabaco, Albay. In 1897, the town mayor noted in an official document that ownership of the land was under question because the San Miguel residents were reclaiming it as communal property (“terreno que reclama el pueblo ser comunal y pendiente de cuestion”), which, since before 1890, had been planted with “coconuts, cacao, banana, bamboo, nipa palm, coffee, lemon trees, sugar cane, abaca, anahao [fountain palm], galyang [root crop], and caragomoy [pandan]” (Supreme Court 2013). Nevertheless, in 1902, Villanueva, in compliance with the Torrens Title Act, again obtained the legal title to the same land. A year before this, about a hundred of San Miguel’s naturales y vecinos (natives and residents) had petitioned the government to reinstate Miguel Berces as their presidente (mayor). The name of Miguel Berces resurfaced in 1902 when, in a suit filed by Villlanueva, he and 13 others were named as “usurpers” of the land in question. In 1905, Señor Juan Loyola, himself among those dispossessed, remarked that Villanueva had sold to some Americans part of the land in question that was near Point Rawis. In 1906, with the Attorney General in attendance to represent the US government, the American judge, Grant T. Trent, ruled in favor of Villanueva.

Up till 1913 suits and countersuits were filed. By 1908, the court records were referring to the so-called “usurpers” as “The Fourteen” appearing in behalf of 305 other evicted residents of San Miguel. One of them was Irineo Bonagua, who, in 1901, had led the signature campaign for the reinstatement of Berces as the town mayor. In 1909, the head of the Presbyterian mission in Albay wrote home in a letter: “Most of the people have lost their land through defective title to a rich man.” In 1913, the Supreme Court upheld the original decision in favor of Villanueva because “the occupants of the land were absolutely destitute of any title,” and they had not acted sooner “in defense of their rights and interests.” “The Fourteen” who fought to keep their land were Miguel Berces/Berses, Saturnino Bon, Leon Buison, Basilio Buela, Alejandro Bogñalos, Idelfonso Buera, Vicente Bolga, Jacinto Brotas, Alberto Beniste, Tomas Berlon, Alejandro Brusola, Fabian Bonagua, Mariano Bonagua, and Agustin Bonagua. One of the defense lawyers for the San Miguel residents was Filipino poet in Spanish Tirso Irureta Goyena.

World War II in Bicol broke out when Japanese soldiers landed in Legazpi on 12 December 1941 and two days later marched into Naga. They met negligible resistance, since most of the USAFFE (United States Armed Forces in the Far East) forces in Bicol were serving in Bataan.

The first guerrilla force against the Japanese in the Philippines was organized by Wenceslao Vinzons of Camarines Norte in December 1941. Prominent people of Camarines Sur organized guerilla units and in March 1942 blitzed Naga. Bikol guerrillas operated between Pasacao and Pamplona and in the districts of Lagonoy and Rinconada in Camarines Sur. The guerillas, led by Constabulary Sergeant Faustino Flor and Teofilo Padua, recaptured Naga in May 1942. Almost simultaneously, Vinzons attacked Daet, Camarines Norte, and Governor Salvador Escudero staged his own offensives in Sorsogon. In July 1942 Vinzons was apprehended and reportedly executed. His patriotism was later immortalized by his birthplace, Indan, which was renamed Vinzons.

Lt Francisco “Turko” Boayes took up Vinzons’s fight against the Japanese. He was joined by two large forces, the Tangkong Vaca Guerrilla Unit (TVGU) and the Camp Isarog Guerrilla Unit (CIGU). The TVGU reportedly ambushed General Takano, the chief military commander of the Japanese in the Philippines, in November 1942.

In 1944, American planes bombed Legazpi, Pili, Iriga, and Naga, destroying many homes, even as most of the Japanese had already evacuated from fear of US attacks. In March and April 1945, Douglas MacArthur’s Sixth Army, aided by Filipino guerrillas, defeated the Japanese in the region. Shortly after, all the guerrilla units in the region merged into the 158th Regimental Combat Team of the US Army. It was divided into two regiments: the first stationed in Legazpi under Major Eladio Isleta, and the second stationed in Naga under Major Licerio Lapuz. The Commonwealth government in Bicol was restored.

After World War II, the agricultural region of Bicol remained one of the poorest and most underdeveloped regions in the country such that out-migration reached “near-epidemic proportions.” Violent disputes intermittently arose between the subsequent landowners and alleged “squatters” on the San Miguel estate well into the 1970s. In 1950, Santiago Gancayco Sr. bought the land and established the Agricultural Management and Development Corporation (AMADCOR). In 1958, his son, Santiago Gancayco Jr, who was also the manager of Hacienda San Miguel, was killed by a group of armed men, one of whom had reported to them the bulldozing of the camote plantations of his relatives, designated as hacienda “squatters.” Nine days later, the group leader, Pedro Borja, was arrested in Cavinti, Laguna, along with 39 others whom he had recruited to start a rebel movement against the government.

Street demonstrations started in 1970, when Bikol student activists of the First Quarter Storm (FQS) came home from Manila to organize in the region. The Federation of Free Farmers (FFF) and youth and students organizations such as Kabataang Makabayan (KM) and the Samahang Demokratiko ng Kabataan (SDK) were organized. The more moderate and Church-aligned Kilusang Khi Rho and Lakasdiwa were also formed to espouse nationalism, justice, and human rights, while rejecting what they perceived as the violent and Communist leanings of their radical counterparts. In Octobercarp 1971, hundreds of students and farmers participated in a “long march” from Naga City to Legazpi, stopping to stage rallies in every town. The private army of an Albay politician attacked the students in Camalig, Albay and followed them to the town church, where they had sought sanctuary.

The most notable of the Bikol activists was Romulo Jallores of Tigaon, Camarines Sur, also known as Kumander Tangkad, of the first unit of the New People’s Army (NPA) in Bicol. He and his comrades formed a guerrilla zone in the Partido district of Camarines Sur in 1970 to 1971. The first encounter of Jallores’s armed group with the Philippine Constabulary (PC) was on 26 August 1971 in San Pedro, Iriga City. Jallores’s armed group moved on to eliminate cattle rustlers, rapists, and other criminals in the localities where they operated. They organized the peasants and implemented “revolutionary land reform.” Jallores was killed by military forces in 1971 in Naga City.

The death of more than a hundred persons, caused by the collapse of the Colgante Bridge during the September fluvial procession of the Peñafrancia fiesta, was read in the popular mind as an omen of martial law in Bicol. A few days later, martial law was declared, media outfits were padlocked, and journalists, clergy, farmers, and student activists were detained. Some of them were tortured; some simply disappeared.

Two types of resistance sprung as a response to martial law: armed and non-armed. Armed resistance was exemplified by student activists going underground or to the hills or both. Former “moderates” joined the radicals, getting killed as members of the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP)-NPA in encounters with the PC and Armed Forces of the Philippines whom they called mga hapon, an allusion to World War II Japanese soldiers.

From 1973 to 1975, after Tangkad’s fall, the CPP-NPA in Bicol suffered setbacks after the “encirclement and suppression” of their Yenan-inspired NPA base around Mount Bulusan in Sorsogon, and the surrender or capture of the regional leadership based there. In the late 1970s to early 1980s, the CPP-NPA recovered and gained strength in Bicol, from Camarines Norte through Camarines Sur, down to Albay and Sorsogon. In the towns, core groups were formed within offices and organizations.

The second form, which was of non-armed resistance, was led by local journalists who, despite having been detained by the military, continued to assert press freedom. From 1976 to the last days of Marcos, the local paper Balalong exemplified Naga free press, mainly in the courageous assertion of press freedom by human rights lawyer Luis General Jr and the anti-Marcos poems of poet Luis Dato. In the mid-1970s, then Integrated Bar of the Philippines (IBP) governor for Bicolandia, J. Antonio M. Carpio, wrote a poem critical of the dictatorship, which he read in an IBP national conference in Manila, with Marcos present as the guest of honor. Concerned members of the Catholic clergy and pastors of the United Church of Christ in the Philippines (UCCP), especially in Albay and Sorsogon, were part of the resistance, sheltering and aiding activists; some of them joined the underground movement during the martial law years.

Some citizens approved of martial law because of the curfew and the discipline and relative quiet it brought, as there were fewer crimes and chaos on the streets. For many, however, it was a time of worsening poverty, marked by fuel rationing, rice queues, and unemployment. Local politicians like Villafuerte and Fuentebella of Camarines Sur, Imperial of Albay, Alberto of Catanduanes, and Espinosa of Masbate sided with Marcos and ensured that their bloodline would sit in positions of prominence.

Martial law was formally lifted in 1981. The Kilusan ng Mamamayan para sa Tunay na Demokrasya (KMTD) or Citizens Movement for Genuine Democracy was organized and at once launched the boycott campaign against Marcos-rigged elections. Four farmers were shot by military elements in what is now known as the Daet Massacre of 1981. When the KMTD leaders Carpio and Grace Magana-Vinzons sought justice for these farmers, they were instead detained.

The assassination of the popular senator Benigno Aquino Jr. on 21 August 1983 triggered mass protest actions nationwide. The Bikol Alliance, which was founded in 1982, published newsletters openly critical of the Marcos administration. Other anti-Marcos organizations founded during this period were the Nationalist Alliance; Bicol Lawyers for Nationalism, Democracy and Integrity Association, also known as Bicolandia Lawyers; Katipunan ng mga Anak ng Bayan, also known as KaAkBay; Bagong Alyansang Makabayan, also known as Bayan; and the Task Force Detainees (TFD) in Bicol. Organizations of various political colors formed an alliance under the umbrella movement called “Justice for Aquino, Justice for All” (JAJA) and side-by-side engaged in protest rallies and marches.

With the rise of the anti-Marcos opposition, local politicians shifted allegiance, as in the case of the legendary “Apat na Aguila” (Four Eagles), referring to the Villafuerte-Cea-Alfelor-Andaya coalition, versus the “Uwak” (Crow) or the Fuentebella-Triviño-Bigay-Ballecer group. Villafuerte joined Cea in the opposition (Briguera, 71; Santos 1994, 35-39). Local politics remained dominated by the dakulang tao, literally “big people,” which was the popular label for wealthy, traditional politicians.

In San Miguel, the farmers’ century-long struggle to regain possession of their land continued. The farmers joined protest rallies in Legazpi City and Tabaco. In 1982, the estate was transferred to Gancayco’s grandson, Celso de los Angeles Jr. Farmers Nelson Brutas, Rodolfo Burce, and 15 others were killed amidst protest actions on March 25, 1983. In 1984, Freddie Burce led 14 farmers in a long march from Tabaco to Malacañan called Lakad ng Bayan para sa Kalayaan (LAKBAYAN) and were later joined by other farmers from Lucena. Finally, on 27 March 1984, the farmers repossessed their own land in San Miguel by order of the Department of Agrarian Reform.

In 1986, Marcos was driven out of the country by the Filipino people in a people’s revolt popularly known as People Power or Edsa Revolt. However, up to the early 1990s, well into the presidency of his successor, Corazon Aquino, activists continued to be harassed, arrested, or became desaparecidos, literally “disappeared.” Sotero Llamas, also known as Kumander Nognog, represented the NPA in the peace talks at the beginning of President Aquino’s term but returned to the hills to head the CPP-NPA in 1987 after the Mendiola massacre. He was captured in 2004, ran as candidate for governor of Albay but lost; he was assassinated in 2006.

The Anti-Subversion Law was lifted during the presidency of former martial law strongman Fidel Ramos. In 1988, Naga City declared a “People’s Ceasefire” and became one of the pioneer Zones of Peace, Freedom, and Neutrality (ZOPFAN) in the country during the September fiesta of 1988. This was achieved at the initiative of the local peace coalition Hearts of Peace (HOPE), together with then-Mayor Jesse Robredo, and despite the non-cooperation of the military forces in Bicol.

Bicol's Economy and Traditional Occupations

Geography defines the region’s traditional occupations: agriculture and fishing. In 2013, Bicol contributed 2.01% to the country’s Gross Domestic Product. Its Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) increased by 9.38% with agriculture, hunting, forestry, and fishing accounting for 23.35% of the economy. The service sector contributed 57%, and the industry sector, the remaining 23.3%. The growth rate of agriculture from 2012 to 2013 was 4.63%; crops, 5.05%; livestock, 1.26%; fisheries, 2.52%; and poultry, 17.69%. The region’s top agricultural commodities are chicken, corn, tambakol or tulingan (skipjack), galunggong (round scad), and eggplant. The region’s production of chicken ranked 11th in the national production in 2013, while its production of corn and eggplant ranked seventh. Rice, coconut, and abaca are major crops. About half of the farming land is planted to coconut, while 20% is planted to rice and 10% to abaca. Bicol ranks second to eastern Visayas in abaca production.

|

| Workers drying abaca in Sipi, Bato, Catanduanes, 2016 (Annielyn L. Baleza, Philippine Rural Development Project - Regional Project Coordination Office V InfoACE Unit) |

Rice, the staple, is supplemented with corn and root crops. Coffee and cacao are also grown. Camarines Sur has the biggest livestock and poultry production and is the region’s main source of carabao, duck, and chicken. Hogs and goats are mostly raised in Masbate. It is also the region’s leader in cattle production, although this is controlled by wealthy families. Camarines Sur is the largest fish producer in the region; Masbate, the best inland fish producer; and Camarines Norte, the most efficient commercial fish producer. The growth of the local population has diminished the supply of fish such as dalag and hito, which were sold in Manila before World War II. Sinarapan ortabios, the world’s smallest fish and a delicacy, is found in Buhi but is now an endangered species. Bicol’s long coastline—the Lagonoy Gulf, Lamon Bay, Ragay Gulf, Visayan Sea, Samar Sea, and Sibuyan Sea—provides rich fishing grounds.

|

| Farmer in Tabaco City drying newly harvested palay near the foot of Mayon Volcano, 2013 (Michael Jaucian) |

Region V has the most iron reserves, comprising 57% of the national total. Its nickel and gold reserves make up 38% and 43%, respectively, of the national total. Camarines Norte has 90% of Bicol’s metals and has the largest deposit of titaniferous magnate sand in the region, followed by Sorsogon. In the country, Camarines Norte has the largest gold and copper deposit, the third largest laterite iron deposit and, with Zamboanga, holds the only lead deposits. In the region, Camarines Sur has the most limestone resources and the only chromite deposit, 3.44% of the national total. Substantial coal reserves can be found in the Batan Island, Albay, Catanduanes, Sorsogon, and Masbate. Except for clay, Bicol’s nonmetallic minerals are often sold as raw materials. Large-scale mining in Rapu-Rapu Island, Albay, and in Prieto Diaz, Sorsogon, has destroyed the environment. Similarly, a cement plant and its related quarrying activities in Palanog, Camalig, Albay has provoked much protest over environmental concerns and labor issues. Kaingin (slash-and-burn cultivation) and, more than this, the logging industry, have eroded Bicol’s mountains. As in the region’s mining industry, which is dominated by such firms as Benguet Corporation and ABCAR-PARACON, a few corporations have monopolized large capital investments in logging. Local furniture making has also suffered from the loss of timber.

In 1999 to 2009, Bicol became one of two abaca-producing regions—the other being Eastern Visayas—that were the worst hit by pests and plant disease. The destruction of abaca plants adversely affects various related businesses. The processed abaca fiber is delivered to traders, who in turn sell these to exporters, rope factories, and pulp mills. Pulp mills manufacture the fibers into fiberboards, which are delivered to paper mills. While the inner sheaths of the abaca plant are processed into fibers for paper and rope, the bacbac (bark) is used for such handicraft items and textile called sinamay. Most communities engage in abaca craft, which consists of machine-made or handmade novelties such as wall decor, mats, baskets, rugs, hats, and slippers, all made from strands of plaited abaca material. These items of fiber craft are exported to the United States, Japan, Australia, and the United Kingdom.

Several other industries sustain Bicol’s economy. Bicol’s exports include gifts, toys, and houseware made from coconut, minor forest materials, and seashells. Tiwi’s clay, especially from the hilly areas of Putsan and Bolo, is used for decorative items such as flowerpots and water jugs, and construction materials such as clay and bricks. Large deposits of red and white clay have given rise to a ceramic industry, which targets the domestic market. The region’s second largest cottage industry is the cutlery of Tabaco, Albay, which includes scissors, bolo, knives, razors, and chisels. Camarines Norte—the gold-rich Paracale-Labo-Panganiban area—is the center of Bicol’s gold jewelry-making industry, specializing in handcrafted filigree. The lasa grass of Catanduanes is used for brooms and dusters. Perlite comes from Bacacay. Cement manufacturing in the region is based on the shale and limestone of Camarines Sur (Balatan-Sipocot-Cabusao), Catanduanes (Manamrag and Tibang), Albay (Palanog in Camalig). Lime quarrying is done in the mountains of Camalig and Guinobatan. Seaweed culture and processing for food, cosmetic, and pharmaceutical purposes have been developed in Sorsogon since 1960. Other regions patronize Bicol’s various food products such as the pili nuts of Sorsogon and Albay, the meat of Masbate, and the seafood of Camarines Norte and Catanduanes.

Video: CARAMOAN Camarines Sur, Mahiwagang Bangus sa Matukad Island, Island Hopping [2022 Bicol Tour Series]

Bicol’s tourism industry is another source of income. Among the more popular sites are the perfect-cone-shaped Mayon Volcano, the Cagsawa ruins, Tiwi’s hot springs, and Misibis Bay Resort in Albay; Lake Buhi, Caramoan, and the Camsur Watersports Complex in Camarines Sur; Donsol for the butanding (whale shark) and Bulusan’s mountain lake in Sorsogon; and Calaguas Island in Camarines Norte. The top tourist destination, however, is Naga City because of the pilgrimage to the Virgin of Peñafrancia.

Video: ATV Ride Adventure in Mayon Volcano Albay: Green Lava Trail, Rates, Price & Fees [BICOL TOUR SERIES]

The Philippine Tourism Authority is developing the Marinawa falls in Bato, Catanduanes into a nature park and resort. Also to be developed in Catanduanes are the Capitol Park in Virac and the Luyang Caves in San Andres, and in Camarines Sur, the Consocep Falls and Atulayan Beach. Provincial festivals such as Albay’s Magayon Festival and Sorsogon’s Kasanggayahan Festival have increased the number of local and foreign tourists.

From 2009 to 2012, the peninsula of Caramoan in Camarines Sur became familiar to worldwide television audiences when it was used as a regular site for eight seasons of the reality show Survivor, which features participants of different nationalities. The media exposure has transformed the place into a tourist spot for swimming, diving, snorkeling, and spelunking.

As of April 2015, Bicol’s labor participation rate was 65.3% and its employment rate, 95.4%. However, despite its resources and opportunities, Bicol remains one of the country’s most economically depressed areas, with the lowest income recorded among the regions. In 2012, the average annual family income was 162,000 pesos or 13,500 monthly. In April 2015, unemployment was 4.6% compared to the national average of 6.4%. In 2010, urban-rural distribution was uneven, with 831,380 of the total population concentrated in urban areas and 4,589,319 in rural areas. In 2000, Bicol lost 38,575 of its population to overseas employment—an increase of around 20,000 overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) between 1995 and 2000. By 2012, the number had risen to 43,546 or 1% of the Bikol population, the male overseas workers outnumbering the female ones by only 7.68%.

Infrastructure for agricultural support remains inadequate. In the 1990s, Bicol averaged a mere 0.33 km of road per sq km of arable land, as against the national standard of one kilometer per sq km. From 2012 to 2013, the region’s national road length increased by 1.4%, from 1,165.16 to 2,344.08 km. Concrete road length increased by 7.5%, from 1,165.16 to 1,252.34 km.

The region has five airports, four major seaports, and six interregional ports. The most important ports for trade and commerce are those of Legazpi City and Tabaco City, both in Albay. Providing additional support for local sea travel are nine more ports located in Masbate, Pilar in Sorsogon, Burias Island, Libon in Albay, Pio Duran, and Siruma in Camarines Sur. The Tiwi Geothermal Complex in Albay is the world’s seventh largest, producing steam-generating energy with a capacity of 275 to 330 megawatts. Together with the BacMan geothermal field in Bacon, Sorsogon and Manito, Albay, it powers the Luzon grid. Five hydroelectric plants, classed as “small,” are found in the following sites: Cawayan in Guinlajon, Sorsogon; Buhi-Barit in Buhi, Camarines Sur; Inarihan in Panicuason, Naga City; Yabo in Pili, Camarines Sur; and Solong in San Miguel, Catanduanes. Nevertheless, electricity is unreliable and more expensive in the region than in Manila.

Located in the typhoon belt, which subjects the region to about 12 storms yearly, Bicol has had annual floods that would inundate 42,000 hectares of prime land for a month. The Bicol Express, which plies the Manila-Naga route, is intermittently suspended due to the damage and destruction wrought by typhoons on the railways. A history of volcanic eruptions and a small landholding system have also contributed to Bicol’s underdevelopment.The Bicol River Basin Development Program was created in 1973 under Executive Order No. 412 “to reverse the downward transitional trend” of the region and in 1978 was expanded to cover Camarines Sur, Albay, and Sorsogon. The program on the Bicol River Basin watershed that succeeded it was closed for lack of funds in 2010.

The Bicol region moved from second to fourth poorest region in the country in the first decade of the millennium. Although mainly still dependent on an agricultural economy, its seven cities, especially Naga and Legazpi, are urbanizing and globalizing. Conversely, the Bikol out-migrants in urban centers and overseas are pouring in material benefits for their families in the region.

Political System

A barangay system was in existence prior to Spanish arrival in 1569. Records show no signs of Islamic rule nor any authority surpassing the datu or chieftain. Precolonial leadership was based on strength, courage, and intelligence. The natives seemed apolitical. Thus the datu’s influence mattered most during crises such as wars. Early Bikol society was family centered, and the leader was the head of the family.

|

| Provincial government building of Ambos Camarines at Nueva Caceres (now Naga City) (American Historical Collection) |

The memory of some of these chieftains who wielded enormous power and prestige has been preserved in the Spanish chronicles and records. Among these were Panga, who reigned over the village of Lupa; Tongdo, the chief of Bua, presently the town of Nabua; Bonayog, ruler of the village of Caobnan; Magpaano, the chief of Binoyoan; and Caayao of Sabang. What is now the city of Ligao in Albay was dotted with affluent villages ruled by Pagkilatan, Makabangoy, Sampongan, and Mabao. Hokoman, the chieftain of the wealthiest of these villages called Cavasi, earned the submission of these chiefs.

The people’s religiosity and respect for authority facilitated adjustment to Spanish leadership patterns. Eighteenth-century reforms introduced the principalia into local office. The gobernadorcillo (town mayor) was selected from 12 electors who were of this class and who were preferably well versed in Spanish. To assure full and timely collection of taxes, Simon de Anda’s 1781 decree stipulated that the cabezas de barangay (barangay heads) be wealthy. Such posts that were exempt from tribute and forced labor were much coveted, and this gave way to election anomalies.

Kinship continued to play significantly in local colonial politics. Political rivalry came between influential native clans, like the families Hernandez and Abrantes in Donsol, and Calmosa and Ubaldo in Matnog. The influences and even their political competition extended to the provincial level, such as in the case of the family of the Abella and Arejola in Camarines Sur. Many of these families later led Bicol’s revolutionary efforts.

|

| Depiction of a policeman (Le Tour du Monde, Nouveau Journal des Voyages by Edouard Charton. Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1884.) |

Revolutionary governments were established under Vicente Lukban and Antonio Sanz in Ambos Camarines, and Anacleto Solano in Albay. Domingo Samson, Justo Lukban, Marcial Calleja, Tomas Arejola, and Mariano Abella represented Bicol in the 1898 Congress in Malolos, Bulacan; and Abella sat in the constitution-drafting committee. Thereafter, several Bicol towns continued to enjoy autonomy under governments sanctioned by General Emilio Aguinaldo. The Spanish officials in Sorsogon remained there until the end of their rule. When they abandoned the province, no provisional government was set up before the arrival of Aguinaldo’s expeditionary force headed by General Ananias Diokno. Spanish laws prevailed during these revolutionary years, particularly in the selection of town officials from the principalia. Hence, when Diokno arrived, he staffed Sorsogon’s provisional government with its illustrious citizens.

Presently, the capital of Camarines Norte is Daet; of Camarines Sur, Pili; of Catanduanes, Virac; of Albay, Legazpi; of Sorsogon, Sorsogon; and of Masbate, Masbate. The region has seven cities: Legazpi, Tabaco, and Ligao in Albay; Naga and Iriga in Camarines; Sorsogon City in Sorsogon; and Masbate City in Masbate. And it has 107 municipalities, which have 3,471 barangays.

Some national executive offices and constitutionally mandated bodies have regional branches in Legazpi. Bicol is served by five regional trial courts and four municipal circuit trial courts. In Congress, Bicol is represented by 16 members (1991): five from Camarines Sur, two from Camarines Norte, three from Masbate, two from Sorsogon, one from Catanduanes, and three from Albay.

As of 2013, each Bicol province has a governor, a vice governor, and 5 to 10 provincial board members. There are 18 mayors and 18 vice mayors in Albay, 12 mayors and 12 vice mayors in Camarines Norte, 37 mayors and 37 vice mayors in Camarines Sur, 11 mayors and 11 vice mayors in Catanduanes, 21 mayors and 21 vice mayors in Masbate, and 15 mayors and 15 vice mayors in Sorsogon.

Notable political names in the history of the region are Imperial, Sarte, Lagman, Borceos, Rayala, Bichara, Ziga, Sabido, Marcellana, and Aytona of Albay; Padilla, Panotes, Unico, and Pajarillo of Camarines Norte; Fuentebella, Cea, Villafuerte, Andaya, Roco, Pilapil, Alfelor, Velarde, Villanueva, del Castillo, Robredo, and de Lima of Camarines Sur; Alberto, Tapia, Almojuela, Verceles, and Arcilla of Catanduanes; Escudero, Gillego, Frialdo, Lee, Michelina, and Diaz of Sorsogon; and Espinosa, Fernandez, Bacumana, Bantiling, Yaneza, Ortiz, Aquino, Guyala, and Medina of Masbate. Dynastic politics continue to color the local scene, and the region is affected by communist insurgency.

Some efforts have been made by a few local politicians, such as Naga City’s late Mayor Jesse Robredo, to provide good governance and services to the poor and to work for peace. Former activists have joined local government and staff NGOs and people’s organizations (POs), working without fanfare on pro-poor measures such as agrarian reform, people’s councils, and peace zones. Notwithstanding such attempts at legal reform, Bicol remains the second strongest rebel stronghold, after Mindanao.

Social Organization, Customs and Traditions

Naming children according to their attributes or the conditions marking their birth was a regional custom; hence names such as Macusog (strong) and Magayon (beautiful). The practice still exists among a few Bikol families.

Traditional courtship, usually prearranged, progressed in several stages: lagpitao or palakaw-lakaw, the initial acquaintance through an intermediary; pasonco, the examination of the prospective match by both parties; pag-agad, the rendering of service by the groom to the bride’s family; and the pre-wedding negotiations setting the dote (dowry). The dowry consisted of the pagdodo (gift to the bride’s mother); sinakat, gift to the bride from a relative attending the wedding; and the ili-nakad, which was an additional fine if the bride had an unmarried older sister. After sayod or the drawing of the marriage covenant, both parties undertook the tronco, a genealogical tracing to prevent incestuous alliances, and finally held the pagcaya, the wedding feast, and the purukan or hurulungan, the bestowing of gifts. Extravagant weddings have continued on to present times, although they are smaller and simpler for the poorer folk. The pamalaye, the meeting of the two families for the wedding agreements, is observed today with greater simplicity, stripped of many of its old formalities. In modern times, Bikol weddings are no longer arranged for familial alliances.

|

| Drawing room of a Chinese trader’s house in Daraga, Albay (Le Tour du Monde, Nouveau Journal des Voyages by Edouard Charton. Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1884.) |

The solemnity of Bikol death rites, however, has never been determined by class, even if this has tended to be more elaborate for higher ranking individuals. The deceased used to lay in hagol (palm tree) coffins. Indigenous funeral rites, called pasaca, were comprised of basbas, the cleansing of the corpse; dool, the dutiful reverence for the deceased; and yokod, the recounting of the deceased’s life. Mourning consisted of the deceased family’s abstinence, displays of grief as in chanting and wailing, and dancing with the toldan, a big clay plate containing a dressed chicken without its innards. Before the actual burial, the deceased’s nearest kin recited “Da-y na ma-olang, padaygosan mo an simong lacao” (Tarry no longer; proceed to your journey).

Religious Beliefs and Practices

Bikol religiosity is deeply rooted. Sometimes Christian faith is expressed through indigenous forms, and indigenous beliefs may assume a Christian face.

Some beliefs and customs related to farming, the life cycle, talismans, and divination survive in the consciousness of the contemporary Bikol. Certain objects are believed to bear special powers, such as the lumay, a love potion; hinaw, a thief detector; and various anting-anting, such as kibal, which makes one invulnerable to sharp objects. The para-bulong or arbulario (folk doctor) is called upon to cure certain afflictions, such as hilo (poison), which gives the stricken person a tubercular appearance but is said to be caused by a supernatural being.

|

| Our Lady of Peñafrancia procession in Naga City, 2016 (Sherwin Magayanes, byaheroph.blogspot.com) |

Indigenous beliefs determine certain actions and forms of behavior. Night birds like kikik or tiktik convey ill omens that may prevent one from venturing out of the house. Dreaming of one’s teeth falling forebodes a close relative’s death. The deceased’s relatives attending the funeral should throw a bit of soil into the grave so as not to be haunted by the deceased. Using the remains of the materials for making the coffin causes bad luck.

The pre-Hispanic pantheon of deities, ranging from bad to good, is to a limited extent preserved. There are certain common expressions that acknowledge the invisible world, such as “Tabi po, maki-agi po” (Excuse me please, I would like to pass by). The Christian God and heavenly host have replaced the supreme god Gugurang and other deities, each of whom had a special function. Ancestral spirits are still invoked in the atang, in which food is offered to them in a postharvest thanksgiving ritual.

Thus, religion pervades daily life and becomes ceremonial during special occasions. Agricultural rites like tamoy, talagbanhi, and rigotiva combine indigenous and Hispanic influences. In Iriga City, tinagba is celebrated after the harvest during the feast of Corpus Christi; and formalities observed therein— pagdalot, pagarang, simbag —could be said to have both political undertones and religious overtones. Towns honor their patron saints during pintakasi. On the 11th of May, tumatarok, a prayer offering and oratory with song and dance, sanctifies a devotion to San Felipe and San Santiago in Minalabac, Camarines Sur. The vivahan may have its roots in the indigenous tradition.This is the welcoming of a new year with shouts of “Viva sa Bagong Taon!” (Long live the New Year) and with songs, food, and money being tossed onto the streets to ensure prosperity for the new year. The Catholic Christmas and Lenten seasons are observed through prayer and rites. Religious rituals include the vesperas, flores de Mayo, lagaylay, pastores, osana, siete palabras, soledad, dotoc, and alleluya, as well as the pasyon and the tanggal. There is also a preponderance of devotional art and literature.

|

| Image of Our Lady of Peñafrancia, Naga City (CCP Collections) |

The most popular and distinct manifestation of Bikol faith is the special devotion to Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia, Patroness of Bicol, who is endearingly addressed as “Ina” (mother). Her feast is commemorated with the procession of the traslacion (transfer) to the Naga Cathedral on the second Friday of September and a huge fluvial parade on the third Saturday of September back to the Basilica.

In 2003, the Roman Catholic Bikol comprised 94.27% of the region’s population, followed by Iglesia ni Cristo members, 1.41%; the Evangelicals, 0.82%; and all the others combined, 3.17%.

Historical Colonial Architecture and Ancestral Houses

|

| View of Albay houses and Mayon Volcano (Le Tour du Monde, Nouveau Journal des Voyages by Edouard Charton. Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1884.) |

In precolonial times, many Bikol houses were perched on trees for protection from the sun and insects. Towns later grew from settlements established near rice plantations, which were scattered throughout the valley and coastal plains. The villages of Handong, Candato, and Fundado in Libmanan, Camarines Sur are believed to have been the site of “pile villages” or lake homes.

|

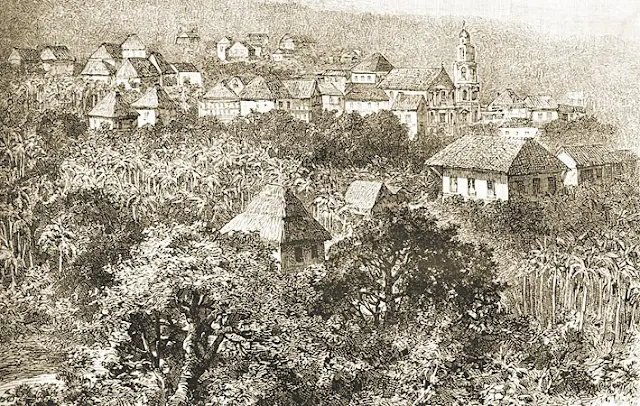

| A village in Albay (Le Tour du Monde, Nouveau Journal des Voyages by Edouard Charton. Librairie de L. Hachette et Cie, 1884.) |

In Sorsogon, towns emerged for various reasons: the repopulation of the coast after the 19th-century Muslim invasions, such as that of Castilla; the establishment of astilleros (shipyards), which generated employment and assured protection, as in Magallanes; the conflict of economic interests, as in Barcelona; and the conflict of political interests, as in Irosin. By and large, community planning has followed the pueblo layout of most Philippine towns, as seen in Nueva Caceres, which is now Naga City, Old Albay, now Legazpi City, and all other towns.

In Naga, a huge stone cathedral looms before a large square. On one side of the cathedral stands the region’s oldest seminary building, Seminario Concillar de Caceres, with its graceful arched portico. Built in the late 1700s, the Seminario, the only one of its kind remaining in the country today, was one of the few schools of higher learning open to Filipinos in the 19th century. On the lateral side of the cathedral once stood the Palacio, residence of the bishop of Caceres, which resembled the Ayuntamiento in Intramuros. On the ground floor of this Palacio, Mariano Perfecto established, upon the invitation of Bishop Arsenio Campo, the Imprenta de Nuestra Señora de Peñafrancia in 1890. Presently the Palacio stands across from the Cathedral. Beside the Palacio is the historic Colegio de Santa Ysabel, one of the first schools for girls in Bicol. In Spanish times, the residences of the Spaniards and wealthier Filipinos encircled this area, while the other locals built their homes in the nearby suburbs.

Churches were erected within 20 years following the arrival of the Franciscans in 1578. Daraga’s present church, overlooking the ruins of the lava-covered town of Cagsaua, Albay, exemplifies folk baroque architecture. It is unique in the country for its solomonica columns, which are twisted columns adorned with leaves. Its facade exhibits ornamental flowers, cherubs, medallions, and even the Franciscan emblem done in the popular colonial stucco method.

|

| Daraga Church in Albay, 2008 (National Historical Commission of the Philippines) |

The style of Naga Cathedral’s facade is even more eclectic; it seems to have variations of the Romanesque, the baroque and neoclassical, and the Moorish. The massiveness of the structure itself may be characterized as “earthquake baroque.” Outstanding are the murals of Naga Cathedral that have been restored several times over the decades.

The Fuentebella house in Sangay, Camarines Sur stands apart from the church, exhibiting stone carvings of religious themes. A few blocks away from the church, Tabaco’s cemetery is dominated by an old arch and a domed cemetery chapel, which is one of the most beautiful in the region. On the other hand, Camalig, Albay is distinguished by its capillasposas, which are outdoor patio altars.

Several ancestral Bicol houses have preserved the architectural features peculiar to the region. The 125-year-old Nuyda house in Camalig, Albay has unusually large capiz panes measuring 7.5 x 7.5 centimeters, arranged diagonally. A penchant for variety is evidenced in the numerous carving designs, particularly of the balusters and panels. Such houses rarely had identical balusters, although among the more common is the Renaissance-style molave balustrade of the Buenaventura-Pardinas house in Guinobatan, Albay. Likewise, houses often had doors with unique designs. In Camalig, Albay, both the Buenaventura-Pardinas house and the Nieves-Guerriba house display characteristically intricate carvings on their molave door panels. Another regional hallmark was the use of volcanic rock for construction, as in the ground floor of the Honrado house in Camalig.

The Pabico house in Daet, Camarines Norte presents an interesting study in interior design. As in many old Bicol and Southern Tagalog homes, its ceiling is painted with cobwebs to attract insects. Unusual geometric patterns over its windows create shadows in the living room. The tracing on its living room arch outlines the owner’s surname.

In the same city stands the Valdeo (Pimentel) house, another Bicol architectural classic, although not necessarily regional in concept. Gothic arches adorn the doorway and the ceiling. Its grilled ventanillas (windows with sliding panels under the window sill) were of the 1870s mode, and its use of cast lead decor was popular from the 1890s till World War II.

The windows are the most practical assets of the Jaucian house in Ligao, Albay. One could look out from behind old-fashioned windows with persianas, capiz windows, and balusters—without being seen from the outside. The nipa panels, when lifted with bamboo stays, shield the occupants from the elements. This fusion of the functional and the aesthetic can be seen in the structure of the Lopez-Jaucian and Pardinas-Buenaventura houses in Guinobatan, Albay.

A 19th-century bahay na bato (stone house) in Tabaco, Albay, originally constructed for Mariano Villanueva, has been declared a Heritage House. It was purchased from him by the British-owned shipping corporation Smith, Bell, and Company, to serve as its Bicol office. In 1965, poet and plantation owner Angela Manalang Gloria purchased it for use as a family residence.

In Sangay, Camarines Sur, the Fuentebella house, which burnt down in the 1950s, was a large stone-and-brick structure linked to a smaller building at the back by a long wooden bridge. Down below was an elegant courtyard with two fountains on each side of the bridge.

The Almeda residence is a landmark along Abella Street. An iron arch above the wide porch is duplicated in wood with lacy swirls over the grand staircase. Polished narra walls and movable partitions give the spacious house a light and airy atmosphere. An innovation is the front stairway inscribed with the names of the family members on the steps. French windows on the second floor have glass panels. Vents above the graceful arches outside the house serve as ornamentation and coolers. Other notable bahay na bato in Bicol are the ancestral houses of the Imperial, Hernandez, Macandog, and Badiong families.

In the Spanish and early American colonial periods, the less privileged lived in native huts located some distance from the center of town, in coastal or inland barrios. These dwellings had wooden posts and were elevated about one to two meters above the ground. Their framework and floor were made of bamboo; their walls, flap windows, and steep hip roof were made of leaves of nipa or cogon grass. These one-room houses, which usually had no divisions, had minimal furniture like a bench, low table, and chests for storage of clothes. On a separate platform connected to the house was a place for water jars.

In the contemporary period, the relatively well-off may live in American-type one-story bungalows or two-story houses with the sala, kitchen, and toilet below, and the sleeping quarters on the second floor. These houses are made of hollow blocks and cement. Wood is used for the second floor of two-story houses. Roofs are of galvanized iron; windows either slide or are of the louvre or vertical-flap types. Makeshift shanties have replaced the nipa huts in urban areas, but these huts still dot the rural landscape.

Arts and Crafts of the Bicol Region

|

| Sample of gold jewelry, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

Paracale, “the golden country” in Camarines Norte, has grown to be the center of a jewelry-making tradition. Although the art has declined since colonial times, some antique styles have survived the centuries, like that of the agrimon (also known as the alpajor and alakdan), the flat necklace chain of the 18th century, and the tamborin, the intricate golden bead necklace of the 19th century. Ely Arcilla, “Manlilikha ng Bayan” Awardee for 1990, continues this Bikol legacy using old tools and methods and the finishing process called sinasapo, which produces a reddish patina.

|

| Gold panning in Paracale, Camarines Norte, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

|

| Goldsmiths in Paracale, Camarines Norte, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

|

| Sample of gold jewelry, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

The Kalanay pottery specimens dug up in Masbate have 15 different patterns combining triangles and scallops, among other designs. Today, this tradition of earthenware making is preserved mainly by women in Bigajo Norte in Libmanan, Camarines Sur, and in Bolo and Baybay in Tiwi, Albay. In Bigajo Norte, the women use the gayangan (pivoted turntable). The men make larger pots, such as water jugs, by a complex forming method including slab molding and coiling. The men also use the turntable to position or support their jars as they paddle, and in turn molding their rims. Other tools used are the hurmahan, a cylindrical tin mold used in forming slabs for jar bodies; pambikal, the paddles; gapu, the anvil stone; hapin, the top part of a broken jar wrapped in a mat or sack; and polishing tools like the lagang from a mollusk or small glass bottles called pambole. The pottery is decorated in three ways: first, the shaping of the sulpo clay of Tiwi; second, for the tibut-tibur storage jars, resin coating using the almaciga resin of Sipocot, Camarines Sur, while the vessel is still hot from firing; and third, for tibut water jars, cementing with pure Portland cement on the exterior and only rarely on the interior of the newly fired jars. As in Tiwi, the Libmanan firing technique is simple. Vessels stacked mouth down on bamboo laid on the ground are covered with grass, husks, and bamboo, then burned with kerosene.

Baybay specializes in novelties and toys called kawatan, which are sold near the town church of Saint Lawrence the Martyr. Bolo, like Bigajo Norte, produces standard items like kurun (cooking pots); gripo (unit faucet water jars); kaldero (kettle-like pots); gulgurek (pitchers); pugon sa uling (charcoal-burning stoves); and masetera (flower pots). The molding sequence in Bolo is much like that of Bigajo Norte. Producing Baybay’s clay novelties, however, requires a special tool kit. The most essential tool is the hurmahan, which can be a suitable item or a model made of an item out of clay. All these molds are initialled by the owners for identification. Other molding tools are the sarik, a pointed piece of bamboo used to bore holes and scrape edges; the pako (nail), which can also be used as the sarik; barasan, a flat tin used to hold powdered shreds; and baras, the powdered shreds, which prevent the clay from sticking to the mold. After firing a pot by the usual method, the potter coats the novelties with commercial enamel paint applied by brush and/or spray gun.

The Bikol excel in the carving of religious statues. Known masters of the craft are Barcenas of Naga, Neglerio of Nabua in Camarines Sur, and Castro Vibar and his sons, although there seems to be a sculptor of religious images in every town. Favorite subjects are the Virgin, San Antonio, San Isidro Labrador, the Santo Niño, and Christ on the Cross.

In the Bulusan municipality of Sorsogon, the foremost handcrafted, trade product is the hat woven from the karagumoy (pandan) leaves. About a million hats a year are produced in Bulusan by women weavers. There is a name for each of the steps in the hat-weaving process. Tukbas is the harvesting of the karagumoy leaves. Han-gulid is the removal of the spines from the sides and midribs of the leaves. Reras is the process of slicing the leaves into narrow strips with tools called the sangnan and rerasan, also called batakan. The unit of measurement for the length of the strips is a dangaw, which is a handspan. The strips are briefly laid to dry under the sun before these are softened by being pressed against a hiyod (bamboo stick) and pulled in the opposite direction. The weaving begins with the balay (crown of the hat), which is in a pinwheel pattern. Strips six dangaw long are used for the balay. Palingkoong is the weaving of the sides of the hat supporting the crown. The paldiyas weave is combined with tugda to create the brim. The sapuy weave forms the edge of the hat’s brim, and pahot is the insertion of the ends of the strips back into the brim to secure the edge. When the hat is fully formed, the last step is gusap, in which strips with ends sticking out are removed. The finished hats, about 10 daily per weaver, are sun dried for a day. Other products woven from karagumoy are sleeping mats and the bay’ong (a rectangular utility basket). The pinwheel pattern of the hat’s crown is a recurring pattern in Bulusan’s woven products.

According to Bulusan lore, the local trade of karagumoy hats reached interisland proportions more than a century ago when Chinese merchants found a market for the hats in the sugar plantations of the Visayas. The plantation workers not only wore the hats to shield their heads from the sun but also folded these to use as shoulder pads on which they carried their load of sugar cane.

The art of abaca weaving has long been developed in Albay and Camarines Sur, although the art has given way to commerce in what has become a lucrative industry. The weaving of traditional textiles of cotton is still found in a few towns of Bicol, notably Buhi, Camarines Sur.

Literary Arts

The patotodon (riddles) reveal a concern with the familiar and material. In the Bikol riddle, the abstract is made concrete. The first part is a positive metaphorical description, and the second part introduces an element meant to confuse, as in these examples translated by Realubit (in Goyena del Prado 1981):

An magurang dai naghihiro

An aki nagkakamang.

(The mother does not move

The child crawls. [Squash plant])

Aram mo pero dai mo masasabotan

Dai mo nasasabotan pero aram mo.

(You know but you do not understand

You do not understand but you know. [Death])

Old riddles are still being learned, but riddling has ceased to be a recreational activity in Bicol today.

The linguistically sophisticated proverbs called kasabihan, arawiga, or sarabihon emphasize values like independence, honor, and humility. The human condition is the central concern of these proverbs. They may be abstract or may use images from nature such as plants, animals, and the human body. For example:

Kon ano an mawot, iyo an inaabot.

(Whatever you choose is what you get.)

An bayawas dai mabungang tapayas.

(The guava tree will not bear papaya fruits.)

|

| Half-woman and half-snake Oryoll seducing Handiong (Illustration by Lou Pineda-Arada) |

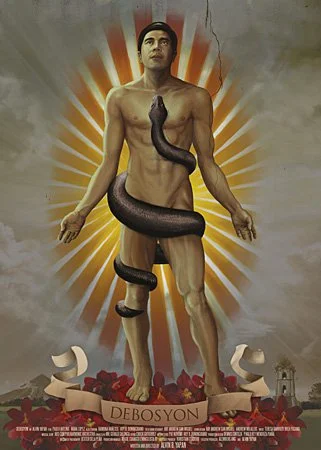

The Bikol culture hero Handiong in the epic fragment Ibalon may have been named after the barrio Handong. Also, there was in the early times a variety of rice called inandong or inandiong. Of uncertain authorship, the epic was first published in 1895 by Father Jose Castaño in Spanish. To date, texts similar to Handiong have been found and sung by an old man in Bato, Camarines Sur. Father Bernardino Melendreras, who served as parish priest in Bicol from 1841 to 1867, was said to have published an anthology titled Ybal, containing Ibalon, the folk epic.

This epic of 60 stanzas speaks of the adventures of Baltog and Handiong. In the beginning, Bicol was a fertile land, where lived the first man, Baltog of Botavara of the race of Lipod. His gabi plants (taro) were the biggest in the land, but they were often destroyed by the wild Tandayag boar. Incensed, Baltog hunted the boar down and tore it apart with his own arms.

Soon after, Handiong arrived in Bicol. For many months, he battled and conquered the beasts with one eye and three throats, winged sharks, wild carabaos, crocodiles big as boats, and finally, the elusive Oryoll, whose body alternated between snake and woman. Having freed the land of all the monsters, Handiong taught the people how to plant gabi and rice, and how to build a boat. His companions, Guinantong, Dinahon, and Sural invented the plow; Dinahon, the household utensils; and Sural, the Bikol syllabary in stone. Handiong and his men also built towns and houses perched on trees to escape the heat, insects, and wild animals.

A great deluge came and destroyed the towns. Three volcanoes erupted and caused Pasacao to rise from the sea. Mountains, islands, and lakes were formed; whole tribes perished in the disaster. Finally, Handiong sent his young warrior Bantong to kill the half-man half-beast Rabot, who could turn people into stone. Bantong attacked the sleeping Rabot and cut its body in two. The warrior then brought the pieces of the monster back to Handiong, who was stunned by the sight.

In precolonial times, the natives wrote many ballads with catchy rhythms about battles, a hero’s exploits, massacres, volcanic eruptions, typhoons, and other natural catastrophes. In this tradition, the “Romance Bicol,” composed by a native, tells about the 1814 eruption of Mayon Volcano. It was translated by Father Melendreras.

Precolonial lyric poetry is divided into awit and rawitdawit, also called orog-orog or susuman. The awit is more sentimental and difficult to improvise than rawitdawit, the more popular form, which is spontaneously composed, using six to eight syllables to a line, four to eight lines to a stanza, and with full or alternate rhyme scheme. Like the ballads, most of these poems have been lost. What remains are developed skills in punning, a breadth of themes from the mundane to the profound, and a partiality to songs. Some general characteristics of Bikol folk songs are a preference for old melodies with relatively new lyrics including a few Spanish words; a tendency to be risqué, often for comic effect; a constant allusion to nature’s beauty; and an abandonment to love’s whims in serenades.

Social life is enlivened by toasts called tigsik, kangsin, or abatayo. These are four-line verses occasioned by happy gatherings whether around a sari-sari (variety) store or during feasts. Toasts can be made on any subject, from religion and tradition to love and sex, and the tigsikan ends when the participants become too inebriated for poetry. For example:

Tinigsik ko ining lomot

Sa kahoy, sa gapo minakapot.

An daragang idudusay an buhay sa pagkamoot

Nungka nanggad an kalayo sa daghan minalipot.

(I toast to this moss

That clings on tree and stone.

A maiden who gives herself away for love

Will never cool the fire of the heart.)

In the old days, a champion emerged from such contests of wit as a poliador, who then would roam about like a wandering minstrel.

The Bikol worldview is expressed, either explicitly or implicitly, in most of their anecdotes. Animal stories abound, involving either tricksters or ungrateful animals, the monkey being a favorite. Heroes and heroines, adventures and misadventures, good and bad spirits animate Bikol fairytales. The more renowned figures are the onglo, who seeks the dark; the taong-lipod or engkanto, who assumes many forms; and the tambaluslos, who pesters the traveler.

Outstanding in folklore is the tale of Juan Osong, counterpart of the Tagalog Juan Tamad. Narrated in some 50 different versions, Juan Osong’s life depicts the common man’s travails and choices when confronted with various challenges. He is born to an old couple. Thumb-size at birth, he grows to be a pygmy with a huge appetite. His impoverished parents drive him away from home. He later fights and defeats two giants who become his servants upon defeat. He saves a kingdom from a dragon, then marries off its princess to one servant. He saves a second kingdom from a fatal odor, then marries off its princess to his other servant. He becomes emperor of these united kingdoms. He frees a third kingdom that had been imprisoned by a wicked giant, then marries its princess. Among Juan’s numerous adventures are those with strong men, a magic hat, a monkey, a goat, a linguist, a dead girl, a governor, and his mother.

Other subjects of Bikol folktales are local heroes such as those in the Aeta tales, patron saints such as those who helped deliver the towns from the Muslims, and “miracle” men such as “Lola” from Joroan in Tiwi, Albay.

Bicol’s creation myths trace the beginning of the universe and man and woman. There is a characteristic dichotomy between the divine and the human, and a frequent use of the bird as a key figure. In one instance, it is the bird that opens the bamboo and brings forth man and woman thus: On the land, Tubigan planted a seed that grew into a bamboo tree. One day a bird flew up the bamboo tree and, as it alighted on the branch, the bamboo shook. Angry because it was moved, the bamboo whipped at the bird in retaliation. As it did, out came from its internodes a man and a woman.

Some of the myths are similar to those of Sabah and Borneo, especially the Sorsogon myth that says that man and woman came from a dog’s tail. The Hispanic influence appears in some later myths of Albay and Camarines, featuring a strong man called Bernardo Carpio.

Combat myths portray the eternal battle between good and evil, as in the fight between the gods, Gugurang and Bathala, and their evil foes, Aswang and Kalaon; between god and the people, as in the victory of Maguindanao, the god of fishes, over the people; and between goddess and man as in “Irago and a Young Man,” one of Bicol’s most captivating stories.

Legends enrich the region’s oral tradition. There is a fascination with giants and bells. Kolakog, the giant, appears in both the origins of Catanduanes and of Ginsa, a riverside place near Pasacao, Camarines Sur. In these legends, Kolakog is a bridge: His wife Tilmag crosses over his legs to plant in the far side of the field, and the natives cross over his extended genitals to flee the Muslims.

The bells have a historic backdrop—the Muslim invasions for which they were endowed with magic. Generally, Bikol legends deal with cause and effect. Things are said to originate as a result of the people’s defiance of nature.

As in other regions, the Spanish missionaries in Bicol used poetry for conversion. Soon the native poets were reciting loas (poems of praise) to begin and end dramatic performances, and korido, poetic romances of legendary-religious or chivalric-heroic origins. Many korido were originally in Spanish and then translated into Bikol by local writers. Several evolved from Bikol folktales. Mag-amang Pobre (Poor Father and Child) and Doña Matia asin Don Juan (Doña Matia and Don Juan) directly relate to the Juan Osong tale, mainly the episode of Juan’s exile.

Among the earliest religious pieces are found in Platicas para todos los evangelios de las dominicas del año 1864 (Sermons for All the Gospels of the Sundays of the Year 1864) by Pedro de Avial and Francisco de Gainza’s Coleccion de Sermones en Bicol (Collection of Sermons in Bicol), 1866. In the 1860s, Bishop Gainza commissioned Tranquilino Hemandez to translate the 1814 Tagalog Pasyong Genesis into Bikol. Soon after, the Pasion Bicol was published under the title Casaysayan can mahal na pasion ni Jesucristo Cagurangnanta, na sucat ipaglaad nin puso nin siisay man na magbasa (History of the Holy Passion of Our Lord Jesus Christ That Will Inflame the Heart of the Reader).

Both priests and laity wrote poems of praise, invocation, and prayer. Some of the first priest-poets in Bicol were Simeon Oñate, Severino Dias, Joaquin Abad, Remigio Rey, and Pantaleon Rivera. Laymen like Manuel Salazar of Bonbon, Camarines Sur, and Antonio Salazar of Malinao, Albay contributed to religious poetry. Rosario Imperial, former mayor of Naga City, used the corrido form to translate English works such as Shakespeare’s classics into Bikol. Moreover, religious playlets like the lagaylay, aurora, and kagharong are in poetic form.

|

| Lagaylay in Camarines Sur, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

After the execution of the Bikol priests, Fathers Severino Dias, Inocencio Herrera, and Gabriel Prieto in 1897, Bikol poetry departed from religion and took on patriotic themes. Mariano Perfecto’s “Padre Severino Dias” was published in Kalendariong Bicol in 1898. Rizal’s poems were also translated into Bikol.

The extant poems in Spanish by Bikol poets are few. Besides critical essays, Angel Fernandez de Celis wrote poems in Spanish. Numerous works composed by Manuel Fuentebella and Bernardo Garcia were published in 1963. Some of the poems that appeared earlier in La Vanguardia, El Ideal, El Debate, and El Renacimiento Filipino are anthologized in Al pie de Mayon, Poesias (At the Foot of Mayon, Poetry).

The production of print literature significantly increased at the turn of the 20th century when ownership of printing machines was no longer monopolized by the church and the system of mass education was established by the colonizers. Following his successful Libreria Panayana in Mandurriao, Iloilo, Mariano Perfecto established Imprenta y Libreria Mariana in 1890 in Bicol. Originally meant to serve the needs of the Church in the region, it was soon printing secular materials in the Bikol language.

In 1903, less than 30% of Bikol 10 years and older could read and write. However, in 1902, a year after the arrival of the SS Thomas, 30 American and 50 Filipino teachers were serving about 2,400 students. By 1918, literacy had increased by about 20%, with Sorsogon reporting the highest percentage at 59%. As a result, the number of publications increased in the first three decades of the century, with more than 20 publications.

The increase in literacy rate did not, however, cause orality to disappear in the region. Extant materials show that, for most of the Bikol, versification remained the dominant means of literary expression in the first few decades of the 20th century. The Ignacio Meliton collection of the University of Nueva Caceres Museum includes clippings of various verse narratives from different publications in the early 20th century. These show that the Bikol narrative tradition continued from the mythical into the empirical and fictional. At the turn of the 20th century, there were versified narratives with a strong empirical basis, such as the following, which leans more toward the news report:

Mapongao na Noticia hale sa Buhi, Camarines Sur

Magna catood cong parabasa

Caining periodico gnaran Bicolandia

Talinga quilingan asin hinanioga,

Can ipag-oosip diit na historia.

Historiang iniho daing iba naman

Cundi si nagniari sa Buhing banuaan,

Nin huli qui Disoy ni Dicay guinadan,

Honra nia hinabon asin dinayaan.

Cundi an sasaco gotoson co sana,

Gnaning di malangcag camong nagbabasa

ta anoman lamang con labilabina,

iquinacaoyam isinisicual pa.