Palawan Tribe of the Philippines: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People | Ethnic Group]

The Palawan, or Pala’wan, who number around 50,000, are one of the three indigenous groups from the main island of the same name. The two other groups are the Tagbanwa, in the central part and the northern Cuyo archipelago, and the Batak, a nomadic Aeta community living in the forest farther north, between Puerto Princesa and Roxas.

The Palawan live in the southern part, starting from the breach in the mountain range between Quezon and Abo-Abo. They call themselves Palawan or Pala’wan, depending on the dialectal variations within the Palawan language. Christian settlers call them Palawanos, a derivation borrowed from Spanish. The Islamized Palawan living in the islets and the seashore along the West Philippine Sea are called Palawanun.

Palawan Island has mountain ranges and peaks, plains, cliffs, and primary rainforests. It rests on the Sunda Shelf, a bridge between Borneo and the Calamianes. Thus, the unique flora and fauna of the southern part of the main island of Palawan are similar to Borneo’s as well as to the other Philippine islands. Some of these fauna are the masek (Malay civet), manturong (bear cat), and pilanduk (mouse deer). Palawan Island is divided by a central mountain chain culminating in Mount Mantaling (or Mantalingajan or Mantalingahan), which is 2,085 meters high. Steep slopes on the eastern coast overlook a narrow coastal plain along the Sulu Sea, while to the west, facing the West Philippine Sea, is a hilly landscape with many limestone caves and an extensive forest. In 1991, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) declared Palawan “Reserve of the Biosphere.”

There are two major Palawan groups according to location: the Palawan-at-bukid or Palawan-at-daja in the highlands and the Palawan-at-napan in the lowlands. The Palawan-at-bukid are communities that live in the remote forests of the Mantaling and Gantong mountain ranges. These isolated Palawan groups have little contact with the outside world and have retained self-sufficient lifeways and a culture dependent on natural surroundings. Similarly, the community living in Catelegyan closer to the peak of Mount Gantong have lived a relatively abundant lifestyle. There are unregistered Palawan communities in Besey-Besey who live some 500 meters above sea level in the area of Brooke’s Point (formerly Bunbun). All these upland communities have opted to live in isolation, totally dependent on the natural forest and seldom going to the coastal areas. On the other hand, the Palawan-at-napan are those who live with migrant communities; no longer practicing swidden agriculture, they have adapted to the cash economy. The Palawan also reside in the southernmost part of the island straddled by the Bulanjao Range, whose highest peak is 1,036 meters. The whole area covers the municipalities of Bataraza and Rizal, which have primary and secondary forests as well as mangrove areas.

The Palawan language belongs to the Visayas group of central Philippine languages and is therefore part of the Malayo-Polynesian branch of the Austronesian family. There are three major Palawan languages. The first is Brooke’s Point Palawan, which in 2000 was spoken by around 14,400 who reside along upland rivers and the coast in the southeast of Palawan Island, from the south of Abo-Abo to Bataraza. The second is Central Palawano, also known as Quezon Palawano, spoken by 12,000 people in 1981. (In 1990, the Palawano population was 40,500.) They live along upland rivers and along the coast in the southwest part of Palawan Island, from north of Quezon to north of Rizal, and east Abo-Abo. The third is Southwest Palawano, spoken by around 12,000 in 2005, and these speakers reside along upland rivers and some along the coast from north of Rizal to the southernmost tip of Palawan island, east side from south Bataraza. However, the Palawan languages include at least 12 dialects, such as the Palawan Penimusan or Islamized Palawan, spoken by those who live along the coasts of the southwest part of Palawan Island and the Tau’t Bato subgroup in Ransang, Rizal. As of July 2005, the Tau’t Bato population was 286 persons, comprising 66 households.

Resettlement policies since the American colonial period have brought in migrants from all over the country, creating a multilingual population that also speaks Ilocano, Cebuano, Ilonggo, Aklanon, and Masbateño. Filipino, though, is the lingua franca in market places, besides being the mandated medium of instruction in school and the official language of government offices.

History of Palawan's Indigenous Peoples

Human beings have lived in Palawan for thousands of years. Archeological diggings have revealed evidence of human presence dating back to the Pleistocene, circaw 50,000 BP (Before Present), down to the Holocene (from 12,000 BP to today). Such pieces of evidence of Homo sapiens (H. sapiens) of the Higher Pleistocene in Southeast Asia are very rare. Tools dating as far back as 30,000 BC have been found in Tabon and the nearby limestone caves of Lipuun Point in Quezon municipality. The most ancient stone-tool assemblage is dated 50,000 BP. Eleven human fossils have been variously identified as belonging to the period from 16,000 to 47,000 BP. All these human remains present the characteristics of anatomically modern Homo sapiens.

Video: Sa loob ng makasaysayang Tabon Cave, Palawan

In later times (4,000-500 BC), the same caves were used as burial sites. The Manunggul Cave provides the most beautiful testimony of jar burial, which is an ancient type of secondary burial. Ground burials with human bodies lying supine are dated at 4,000 years ago. Considered the earliest human cremation in Southeast Asia was the one found at the mouth of Ille Rockshelter in El Nido, Palawan dated between 9,280 and 9,425 BP.

In 1521, shortly after Magellan’s death in the hands of Lapu-Lapu on the island of Mactan, the remnants of his expedition, commanded by the Portuguese João Carvalho, landed on an island called Pulaoan on their way to the Spice Islands. Being met with hostility by the first settlement that they came upon, they docked at another village called Dyguasam (now Puerto Princesa), where the people were friendlier. At a third village, both the chieftain and Carvalho held a blood compact, whereby they each cut themselves on their chest with a knife and then wiped the blood-stained tip on their tongue and forehead. Because the Spaniards stayed on Pulaoan for a month, they had ample time to observe that it was a large island rich with rice, ginger, swine, goats, fowl, bananas of various sizes, coconuts, camotes, sugarcane, and turnips. The inhabitants were rice cultivators, who cooked their rice in bamboo tubes by placing the fire over—not under—these. They also made rice wine. For weapons, they had blowpipes; the wooden darts were tipped with poisoned iron or fish bones. At one end of the blowpipe they attached a pointed iron head so that it doubled as a spear when they ran out of darts. For recreation, they held cockfights where bets were placed. The Spaniards bartered brass rings, chains, bells, knives, and copper wire for provisions of goats, swine, and fowl. After a month, the Spaniards were eager to push on, but a Christianized “Portuguese-speaking negro” native reneged on his promise to guide them to the Moluccas. Instead, the Spaniards captured two men whom they forced to be their guides.

Months later, in September 1521, while at sea, the Spanish stragglers captured the chief of Palawan himself, who was sailing home from Borneo. They held him hostage in exchange for 400 measures of rice, 20 swine, 20 goats, and 150 chickens, which his people had to deliver within seven days. When he was freed, the Palawan chieftain gave the Spaniards an additional quantity of coconuts, bananas, sugarcane, and jars of palm wine. Because of his generosity, the Spaniards returned some of his knives and arquebuses and gave him a yellow damask robe and a bolt of cloth 25 meters long; his son they presented with a blue cloak; and his brother a green robe. Later, they would barter with the natives of Butuan two large knives that they had seized from the Palawan chieftain for 17 lb of cinnamon.

For the next three centuries of Spanish rule, the colonizers failed to establish their stronghold on the island because it was under the control of the Sulu Sultanate. In the 19th century, malaria and piracy prevented the Spanish Augustinian missionaries from settling on this island.

In the 1830s, strongman Sharif Usman rose to power and wielded political and economic control over the island. Usman was a Bornean trader with Arabic blood who had married a sister of Datu Buyo of Sulu. Usman represented the Sultan of Sulu and controlled trading in the Marudu district, Balabac, and Southern Palawan. But his colorful career was aborted by James Brooke, the English explorer who became “the white rajah” of Sarawak. Brooke sought the help of British maritime forces and killed Usman in a naval operation at Marudu River in 1845. With the death of Usman, a Tausug leader named Datu Alimuddin controlled the trade in Southern Palawan. In the 1850s, James Brooke visited southern Palawan and gave the name Brooke’s Point to the place that is now the municipality of the same name.

It was during the American period that Christian migrants began settling on its coastal areas and lowlands in continual waves. After World War II, the national government continued the policy of resettlement in frontier areas, which it declared as public lands but were actually the ancestral territories of indigenous peoples (IPs). The uncontrolled influx of migrant settlers created complex consequences that drove the Palawan deeper into the forests. First, the newcomers had little knowledge of forest ecosystems on which they wrought wanton destruction when they cleared the forests. Second, the building of roads gave the migrants easy access to new lands in the plains and hills. In 1957, for example, a national road was built southeast from Narra to Brooke’s Point, and in 1962, another road was constructed southwest traversing Quezon town.

Third, the settlers, ignorant of indigenous land rights, considered the Palawan areas as theirs for the taking. The cumbersome bureaucratic process of acquiring legal land titles discouraged the majority of the migrant settlers from undertaking it. Hence, they would simply occupy the cultivated land temporarily abandoned by the Palawan farmers, who had only meant to let it lie fallow as an essential practice in swidden agriculture. “Squatting” on these “vacant” lands became an efficient means of acquiring property. However, it resulted in the widespread eviction of the Palawan from their territories, particularly those situated along the highways.

Deprived of their means of subsistence, the Palawan allowed themselves to be absorbed into the migrants’ cash economy. In Abo-Abo, some migrants paid the Palawan for clearing the forest; others gave them commodities such as tobacco and sugar in exchange for their services. There were those, too, who were swindled out of their land. These were insidious ways by which the migrants grabbed the Palawan’s ancestral lands. On the other hand, those who refused to give up their ancestral territories were subjected to grave threats from the migrants.

Moreover, the migrants bore an attitude of cultural superiority and paternalism over the indigenous peoples, who were then officially called “cultural minorities.” Thus the Palawan suffered from discrimination and ridicule from them. In the forest interiors, however, the Palawan continued to practice autonomy, swidden farming, and their indigenous religion, thus preserving their cultural identity and reenforcing the Palawan sense of community.

From the 1960s to the mid-1970s, the Commission on National Integration (CNI), which was tasked to enable the Palawan to legally regain their lost land, only exacerbated the Palawan’s displacement. Its prescribed resolution to land disputes was to persuade the Palawan to accept compensation for lands occupied by settlers. At Brooke’s Point, the CNI facilitated the formal transfer of ownership of at least 46 Palawan lots to settlers. Through this means, whole communities of the Palawan in Abo-Abo were similarly displaced.

Although the barter system continued until 1975, the dominance of the migrant culture ushered in market forces into Palawan communities heretofore alien to them. After some initial resistance, the Palawan learned to consume processed foods, primarily canned goods. Such a diet contributed to the lowering of their life expectancy from the previous average of 100 to 120 years.

Mining explorations that began in the 1960s led to the discovery of nickel deposits in Rio Tuba in the Mantaling mountains in 1967. In 1975, the Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corporation started its mine construction for the extraction of minerals to be shipped to Japan. This triggered a chain of disastrous effects on the Palawan living in the area, such as those in Barangay Panalingaan. Lowland migrants, attracted by the economic opportunities opened up by the mining activities, again encroached in these Palawan ancestral lands, which they tilled with chemical fertilizers and pesticides. These created an ecological imbalance that propagated weeds, rats, and other pests. Moreover, the two-way traffic of ships transporting equipment, supplies, and mineral deposits is believed to have brought in unknown insects that multiplied and attacked the Palawan’s crops.

In the 1970s, during martial law, President Ferdinand Marcos visited Singnapan Valley in Barangay Ransang and met some Palawan who normally shelter in caves during the rainy season. In September 1977, President Marcos launched a research project on the Palawan subgroup, which the government team subsequently called Tau’t Bato, an exonym. Rice, clothes, and other commodities, transported in helicopters that landed in their midst, were distributed to them. The president’s team was headed by National Museum of the Philippines director Godofredo L. Alcasid and Presidential Assistance on National Minorities minister Manuel Elizalde Jr. They explored caves that were sacred burial sites of the Palawan. One significant discovery was a set of petroglyphs on the wall and ceiling of Ugpay Cave, where they also found pieces of stone tools.

In May 1978, press announcements about the discovery of the Tau’t Bato were made by First Lady Imelda Marcos and daughter Irene. On 12 June 1978, President Marcos, through Proclamation No. 1743, declared 23,000 hectares of the Singnaban Valley a “reservation area for anthropological and archeological studies,” thus underlining the significance of the ancient rock art and the Tau’t Bato as cave dwellers. All the artifacts were subsequently collected from these caves. However, the president’s team also surveyed other caves not frequented by the Palawan. This gave rise to rumors that these caves were being used as repositories for Marcos’s hidden wealth. Hence, from 1980 to 1990, treasure hunters scoured the rock shelters and caves for his hidden treasures.

|

| Palawan family moving into the caves, River Sumaran, 1992 (Photo by Pierre de Vallombreuse in Taw Batu: Rock People by Charles Macdonald. Albert Kahn Museum, 1994.) |

More than the colorful lore on the Tau’t Bato cave explorations initiated by President Marcos was the iniquitous legacy of the Marcosian rule: the strategy of economic development based on debt dependency, foreign investments, and natural resource extraction. Government administrations after the fall of the Marcos dictatorship continued this development formula. Thus, in Palawan Island, extractive industries such as mining have been supported by the alliance of big businesses, foreign investors, and local politicians. The 1991 Local Government Code gave the local officials even freer rein over their region’s resources.

International institutions and the national government have made attempts to protect Palawan’s ecological system. In 1990, the UNESCO declared the Palawan archipelago a Man and Biosphere Reserve that must be protected, being a habitat of endangered species and the home of marginalized indigenous communities (UNESCO 2013). Republic Act 7611, also known as the 1992 Strategic Environmental Plan, provided legal measures for the environmental protection and administration of Palawan’s ecosystems. The Mining Act, passed in 1995, failed to compel mining companies to ensure the safe disposal of toxic wastes, the rehabilitation of abandoned mines, and the protection of biodiversity and indigenous culture. The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) in 1997 contains provisions attempting to rectify loopholes and errors in the preceding laws and encourages the Palawan communities to apply for titles to their ancestral domain.

Such measures, however, are inadequate to protect the biosphere of Palawan island. In-migration continues unabated. In 2000, a road built around the island attracted thousands more new settlers. Mining activities continue to destroy the forests, ruin sacred sites, cause floods, and silt rivers. Heedless of these catastrophes, President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo in 2006 called for the revitalization of the mining industry, which was an open invitation to big mining companies to continue exploiting the territory of indigenous peoples. The administration of President Benigno Aquino III which followed did not also push for any ban on large-scale mining operations in the country. In the late 2000s, big mining companies such as the London-based Toledo Mining Corporation were poised to expand into the ancient lands of the Palawan. The Japanese-backed Rio Tuba Nickel Mining Corporation (RTNMC) also applied for the exploitation of a new site in the Bulanjao range. MacroAsia, owned by taipan Lucio Tan and backed by Chinese investors, was planning to operate in Mantaling and Gantong ranges, which supply drinking and irrigation water to lowland communities. Even during that time, there was already fear that MacroAsia operations would destroy vital watersheds, natural forests, and the ancestral home of the Palawan.

In 2009, Palawan and migrant community leaders as well as heads of other ethnic groups organized the Ancestral Land Domain Watch (ALDAW) to protest the potentially destructive impact of mining on their territories. Hence, in the same year, Presidential Proclamation 1815 declared the whole area covering the municipalities of Bataraza, Brooke’s Point, Quezon, Rizal, and Sofronio Española as the Mount Mantalingahan Protected Landscape (MMPL). A product of rigorous scientific studies, the MMPL proclamation reaffirms the struggle of the Palawan in protecting their pristine environments.

In 2011, as the anti-mining campaign was just gaining local and international support, Dr Gerry Ortega, an environmental activist and fearless radio broadcaster, was assassinated. Less than a month later, this led to a multi-sectoral coalition, the Save Palawan Movement, which was launched with a signature campaign to deliver the message of “No to Mining in Palawan” to the government.

In 2011, nine Palawan leaders traveled to Manila to protest the privileges being granted to MacroAsia at the price of the indigenous peoples’ rights. They held a dialog with media, congressmen, and officers of the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) and presented the following main points: 1) that the NCIP, in collusion with MacroAsia, had used “fake” tribal leaders to sign a certificate in favor of the mining application, and 2) that there was a growing military presence in their ancestral domain.

Meanwhile, the palm oil industry has caused further deforestation, consequently destroying the habitat of numerous species of flora and fauna, and causing climate change of disastrous proportions. In Palawan, the expansion of oil palm plantations, with investments from Malaysia and Singapore, began in the 2000s. An ordinance of the provincial government to establish the Palawan Palm Oil Industry Development Council further encouraged investments and the development of plantations, milling plants, and refineries. Financing for oil palm plantations also came from the Land Bank of the Philippines. By 2010, some 40,000 hectares had been converted to such plantations in Aborlan, Narra, Espanola, Brooke’s Point, Bataraza, Rizal, and Quezon. Oil palm plantations have encroached into Palawan areas meant for shifting cultivation, medicinal plants, food, rice, and materials for house construction.

Moreover, climate change, which has become more manifest since the 2000s, is causing irreversible changes in the life patterns of the Palawan. The sun’s heat has grown harsher, and there have been cases of the Palawan falling extremely ill when they worked on the fields beyond nine in the morning for three straight days. On the other hand, excessively heavy rains during the wet season can drown the crops. Unpredictable weather has wrought havoc on nature’s balance and promoted the growth of pests and weeds. The disruption in the cycle of flowering plants has even affected the bees’ production of honey. Some species of flora and fauna are dying, and forest products are decreasing.

The Livelihood of the Palawan Indigenous People

The economic system of the Palawan consists of two types of activities: foraging, hunting, and fishing on one hand, and upland rice cultivation in the uma or kaingin (swidden farm), on the other. There is gender-based division of labor, although this is neither absolute nor marked by prohibition or exclusivity. Women carry out most of the agricultural tasks, mainly clearing, weeding, and harvesting rice. They also harvest grains and tubers and collect edible plants and mushrooms in the forest. They fish with hook and line or with a hand net. They prepare the food, look after the children, and weave basketry. Men cut down the trees to make a clearing for the uma; they may also participate in agricultural work such as planting and weeding. Their favorite activities, rarely done now, used to be hunting with a blowgun or with dogs and spears, and fishing with a trap or with goggles and a spear gun. They are also responsible for building the banwa (houses) and the lagkaw (rice granaries).

The production of rice, the staple food, in lowland areas varies in the highlands. In contrast to the fertile soil found in the hilly area of Punang (a former rice granary), the landscape of Makagwa and Tamlang valleys is abrupt, their upland fields are smaller, and their soil is less fertile. Swidden agriculture requires a low population so that there is sufficient space and time for fields to lie fallow and for secondary forests to grow. This ensures the proper rotation of land use in each planting cycle. In the uma, rice is grown in association with other grains such as millet, sorghum, and corn, and various tubers such as taro, yam, and cassava.

Private ownership of land is a notion and practice totally alien to the Palawan way of thinking as well as to their social and moral values. The notion of land ownership was introduced by new Christian settlers, while the highlanders still consider themselves as the heirs and custodians of the land where their ancestors have lived, cultivating upland rice, planting fruit trees, and collecting almaciga resin. In this way, they feel rooted to their ancestral land. In the highlands, the main source of cash income used to be bagtik, the resin from huge almaciga trees. It is processed into copal, which is used to make lacquer. However, the Palawan do not benefit much from this market. Bagtik gathering, which requires hard labor and transportation from the highland forests to the concessions on the foothills, has introduced the national currency into Palawan economy. However, it remains a very modest source of income and, with the new economic policies, is presently under threat. Those who benefit more are concession holders who are outsiders, such as Christians and Muslims.

The Palawan may cross the mountain range in search of medicinal plants and other such non-timber forest products as honey, rattan, beeswax, edible nests, and palm tree products. From ancient times until World War II, they traded their rice and these forest products for the seafarers’ gongs, jars, plates, celadons, blades, and brassware. It was conducted silently, with both parties avoiding direct contact by leaving their trade goods on the seashore.

Today, the territory of the Palawan has been drastically reduced in the coastal plain and the foothills. Furthermore, it is being threatened by nickel-mining multinational companies such as MacroAsia and Ipilan Nickel Corporation, and, more recently, oil palm, cacao, and rubber plantations. These monocultures have spread extensively from the lowlands to the edges—some even to the core zones—of the forested areas in the highlands, such as Mount Gabantong and Mount Mantaling.

The Palawan in the municipality of Española have experienced the disastrous effects of the oil palm plantations. Chemicals have decimated plant and animal life, resulting in the diminished population of birds and freshwater animals, and the dramatic decrease in non-timber forest products. Banned chemicals in the United States, such as Furadan, have been used in Palawan to eradicate the local variety of beetle infesting oil palm plantations. This has only caused the insect to migrate to the Palawan’s coconut trees, which have been thus decimated. Palawan elders are concerned about the threatened survival of their ethnobotanical heritage, particularly their medicinal herbs, the extinction of which will also mean the extinction of the Palawan people.

Gainful employment in such agricultural plantations as oil palm was promised to the Palawan. However, only 25 workers were employed per 150 hectares in Iraray, a very low employment rate in contrast to the rosy picture presented by palm plantation proponents. Furthermore, the oppressive working conditions include excessively long working hours, inaccurate recording of working days, exposure to hazardous elements, and insufficient benefits. On the other hand, those who leased their lots for as low as five thousand pesos a year cannot reclaim their lots unless they were to pay three million pesos, ostensibly to defray the cost of development. This was the case of one Palawan trying to retrieve his 25-hectare lot.

The MMPL is an important legal instrument to protect the Palawan environment. It has an estimated economic value of at least 5.5 billion US dollars and is responsible for providing basic ecological services such as water, flood control, soil fertility, and non-timber forest products. The declaration of Mount Mantaling as a protected area bans the kaingin farming in primary forests as well as the hunting and gathering of endangered plants and animals in protected zones. However, the upland Palawan are allowed to continue their traditional practice of descending to the shorelines to gather food from the mangroves and reefs, and to sell non-timber forest products to lowlanders.

On the other hand, the lowland Palawan are integrated in the market economy and coexist with settlers and migrant families. They have developed such sources of income as copra production, wet rice farming, animal raising, and selling of cassava flour. Therefore, they are not as drastically affected by mining, oil palm plantations, and climate change.

Ecotourism provides alternative livelihoods to the Palawan. The Singnapan Valley has become a tourist destination. Members of the Tau’t Bato and other Palawan subgroups undergo training to become trekking guides and porters. The local knowledge of Palawan guides is essential, particularly for mountain climbers going to Mount Mantalingahan via the Ransang trail because the trek lasts for at least three days and every stopover must have a source of potable water.

Government institutions like the Department of Trade and Industry, fair trade organizations like the Non-Timber Forest Products Exchange Programme, and small entrepreneurs like Asiano Arts and Crafts provide alternative livelihoods by promoting locally produced handicrafts such as Palawan baskets and sculptures.

Palawan Tribal System

The Palawan ethos rests on three values: adat at pagbagi (custom of sharing), ganti (parity in exchanging), and tabang (mutual help) between sisters, husband and wife, and the elder and the younger.

The panglima (headman) of each village is either the father or the uncle of a group of sisters and their first cousins. In order to maintain equilibrium in society and to ensure that a moral code that is based on nonviolence, sharing, and mutual help is followed, the headmen are highly knowledgeable in adat (custom law) and experts in bisara (jural discussion). Such a role and function implies that a headman has prestige and some authority, though not necessarily a superior economic status or political power.

The ukum (judge) and the salab (intercessors) see to it that sara (the law) is respected and implemented. They also mediate in conflicts and see to it that physical and verbal violence are avoided. Here is an extremely pacific society from which conflict is not absent but is always controlled and restrained by the mastery of “thinking and speaking,” which is the etymological content of the word “bisara,” from the Sanskrit vi-cara, meaning “thinking,” “argumentation,” or “to make a judgment.” Bisara is an extremely codified system of verbal exchange, elegant and calm, transpiring between experts.

Traditionally, within the framework of their adat, the Palawan cannot defend themselves against violent outsiders, as they have no institutional means of organizing violence. However, they know how to avoid it by speaking, and in this respect they are exemplary though extremely vulnerable. When a social contract is to be established or an agreement reached, when disagreement arises or when an open conflict takes place, the Palawan gather in the large keleng benwa (meeting house) in order to think and discuss, deliberate and decide, make an ukuman (judgment), and agree on the penalty to be imposed. By doing so, they aim to restore peace and harmony in the local community. The mamimisara (masters of discussing) have undergone a period of long training, having been exposed to this verbal art since childhood. As adolescents, they act out roles under the guidance of the magurang (elders). Such sessions are conducted in the evenings.As adults they have to memorize numerous cases settled under their jural law.

Burak at baras (flowers of speech) represents not only their art of rhetoric but also their art of relating to one another, discussing openly and courteously in a highly stylized attempt at solving problems and resolving conflicts within the community. The rhetorical devices and strategies of the Palawan include (1) the paribasa, a stringing together of politeness devices, which may take such forms as astonishment, feigned ignorance of an event, feigned anxiety, and allusion to a serious but apocryphal event; (2) baliwat, an inversion device as a way of being tactful, such as the use of a negative expression instead of an affirmative one (e.g., one blames one’s self when the other is in the wrong, this way being a more elegant way of proceeding and is more likely to make the other person ponder); (3) lilibu, a convoluted, roundabout way of speaking, as opposed to the matigna, the direct or straightforward way; (4) mababa baras, speaking in words heavy with implication, and mabwat tugna’an, speaking with words that are long in meaning; (5) ellipsis, a widely used device, where whole phrases and even clauses can be implied; (6) ulit-ulit, repetition and redundancy through the accumulation of synonyms, which is used to emphasize one idea ; (7) sindir, metaphor and simile in poetry and jural debate (e.g., comparing manuk or chicken or small hen to a girl or a fiancée; tampur or cockfight to marriage; luwakatnyug or coconut shoot to a young man; damdam or mattress to adulterous relations); (8) alagad, a transposition device, a shift of register, such as treating serious matters in a light, playful manner; (9) hyperbole, a clause marked by exaggeration (e.g., magansur, meaning“to burn to ashes,” or manutung, “to burn the field or to set fire,” to express the idea of punishment); (10) ma-intur maras, a subtle speech form marked by great prudence, avoiding extremes of both assertion and negation; (11) badyu at baras, literally “clothing one’s word” or speaking covertly or in an indirect way, and thus another elegant way of speaking; (12) bisara paryab-ryab, a speech carefully worded to give a pleasing effect while conveying a veiled reproach for the wrong that the listener has done; and (13) karang, a general term for a sophisticated rhetorical or poetical composition of two couplets, each line having seven syllables, and with rhyme and assonance. All these figures of speech require high levels of thinking skills and mastery of an elegant way of speaking, which the Palawan greatly enjoy.

Each bisara, as a mode of argumentation and debate, follows an outline and contains figures of speech linked to the various jural cases. In this respect, bisara is not a conversation. There is a convergence of proofs, appreciation, and evaluation leading up to an ukumanand an i’un (agreement). The final goal is renewed harmony as the judge concludes the case with the formula statement: “Pwas at sala-ya” (His/Her mistake is over).

The balyan (shamans), whose primacy lies in their spiritual leadership, play an important role among the Palawan. Renowned shamans who exercised great influence in the Kulbi-Kanipaan river basins and adjacent territories were Pedjat, Nambun, and Tuking, who were widely sought for healing, blessings, and spiritual advice.

During the American colonial period, a shaman named Damar, who lived in Abo-Abo, was a folk hero believed to have mystical powers. He was arrested thrice by authorities for rallying the Palawan to reclaim and reoccupy the forests. Inspired by the memory of Damar, the Palawan in the 1980s organized a corporate foundation, the Pinagsurotan Foundation, to secure land tenure through government lease agreements. The move was opposed by settlers wary of the prospect of the Palawan getting 25-year lease agreements on specified tracts of land, with the option to renew after the contract expired.

The local leadership system instituted under martial law was the barangay. But this local governing body has always been dominated by settlers who consider the Palawan ancestral domain as alienable land. Instead of getting the participation of the Palawan as the original inhabitants in the area, the barangay system has legitimized the dispossession of the Palawan (Lopez 1987, 243). The most important legal instrument giving the Palawan the power to govern themselves in their ancient territories is the 1997 Indigenous People’s Rights Act (IPRA). By virtue of the IPRA, the Palawan, with the support of civil society and international agencies, have formed their own organizations, such as the Bangsa Palawan Philippines, Inc. (BPPI). In 2009, it successfully acquired the legal title to their ancestral domain, consisting of 69,735.23 hectares of Barangay Panalingaan, Barangay Taburi, Barangay Latud, and portions of Kanipaan and Calasian in Rizal town. Part of Barangay Panalingaan is within the MMPL protected area, which was declared in 2009.

The IPRA includes the principle of Free Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC), which gives IPs the right to approve or reject projects and activities within their ancestral domain. All projects must therefore pass through an FPIC process of consultation with the Palawan council of elders and communities. Yet in 2011, no FPIC process was conducted among the Palawan when nonindigenous peoples cleared ancestral lands in Barangay Tagusao, Quezon, and Barangay Iraan, Rizal, for oil palm plantations.

Despite their traditionally peaceful and nonconfrontational character, the Palawan have proven their capability for collective action. In 2014, the Coalition against Land Grabbing (CALG) was established to unite over 4,000 IPs and non-IPs to fight against the expansion of oil palm plantations in Palawan Island.

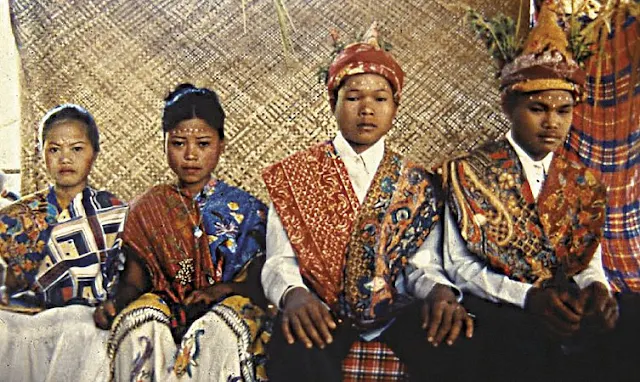

Palawan People Culture, Customs and Traditions

Palawan society is characterized by a bilateral kinship system and the absence of any kind of hierarchy—that is, no title, rank, class, or caste. Roles are distributed between men and women, elders and youths, relatives by blood and by marriage, and their neighbors. These make up the rurungan (village), which is a small, local, and tight-knit community.

The Palawan neighborhood is based on camaraderie, not necessarily on kinship or legal ties. A neighborhood may be known by its specific location or by a highly respected resident elder. The authority of the magurang stems from their influence by virtue of their kinship role or their wisdom and knowledge of traditional law.

Rites of passage of primary importance are courtship and marriage. Courtship is an elaborate practice. Young women receive their suitors in houses on stilts. The men declare their feelings with endearing words or sing love songs with their kutyapi or kusyapi (two-stringed wooden instrument or lute). Marriage is celebrated as a crucial turning point in life. Monogamy is the norm, but polygamy is allowed. So is divorce, which is a common occurrence. Though the men wield authority, there is relative equality in the roles and relations of men and women. Both have their own special skills, and one is not considered superior to the other. Women, married or not, are not constrained to wait for the men to decide on family or social matters. Palawan society is egalitarian, based on a respectful, courteous relationship between its elders and its younger members. They give importance to tahyun (consensus decisions) within the family and among households. However, it is important for the individual to express kekwan (personal will), to exercise empe (the right to refuse), and mugad (to go away). Being compelled to do something against their will results in eperikasen (frustration or hopelessness). Pegawidan (preventing a person from fulfilling a wish) and rumbu-en (pushing an individual to the extreme) may undermine a person’s spirit or mental state and may lead to suicide. Therefore, the Palawan avoid situations where there is no alternative. Social etiquette includes meketupad (keeping a promise), iingkut (asking for advice) from elders, and respect for kebentelan (truth). By nature they avoid conflict, so they dissociate from people who are melagak (too eager), mesibag (insatiable), and meringit (hot-tempered). They also avoid people with magdeleg ey mata (smoldering eyes); ipe leu (quarrelsome by insulting others), and keyaatan (hostile). The ideal social behavior is ingasi (compassion) because it promotes good community relations. Other positive social attitudes are bungbungan (cooperation), ibgey (generosity), tahak tahak (sharing), mekesarida (being considerate), galang (respect), and tume-u et maap (being apologetic when declining an offer). Such traditional codes of conduct prescribing nonconfrontational, nonaggressive behavior have not prepared the Palawan to deal with unscrupulous and cunning politicians and businessmen.

Solidarity between siblings provides an individual with unconditional support and generous help. Following the adat at mamikit (custom of adhering), a husband lives at his wife’s place of residence and is thus integrated into his wife’s group of sisters, under the authority of their father or uncle. His in-laws expect obedience; his wife and children expect his love and dedication. While he has to serve his father-in-law, he will in turn expect the same behavior from his future sons-in-law.

Palawan People Religious Beliefs and Practices

In Palawan cosmogony, Ampu, the Master, by his reflection, wove the world and created several beings; hence, he is also called Nagsalad, the Weaver. He is the supreme deity; a protective, watching presence, always invisible to taw banar (the people). In the verticality of the worlds, Andunawan is his abode. While people live on dunya (earth), another benevolent and protective deity stays in the lalangaw (middle space). This is Diwata, a mediator between humans and Ampu. Since this world is made up of a vertical succession of realms, conceived as a series of either seven or twice seven “plates” or levels, there are other invisible beings and deities. However, the pantheon is not organized in a fixed, pyramidal order. The langgam, also called saytan —a word borrowed from Arabic and brought into the region by the Malay seafaring people—are ambiguous beings that can be harmful to humans as taw maraat (evil doers), malevolently bringing anguish and sickness. But these can also be taw manunga (good doers), benevolently providing inspiration and knowledge.

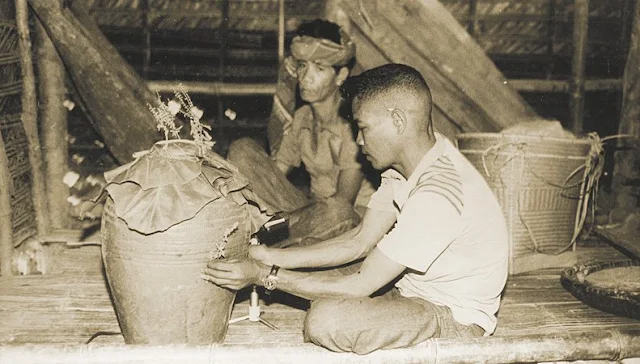

|

| Rice beer ritual in honor of the master of rice Ampu at Paray, 1981 (Photo by Anna Fer, Nicole Revel Collection) |

Other deities are more directly associated with human destiny: Ampu at Paray, the Master of Rice; Linamin at Barat, the Lady of Monsoon Winds; Linamin at Bulag, the Lady of the Dry Season; and Upu Kuyaw, Grandfather Thunder. They are linked to natural phenomena and to a socio-cosmic order that relies on the respect for adat, such as the rule prohibiting incest. Its violation can destroy this earth, triggering off earthquakes, landslides, tsunami, and a deluge. Innumerable beings such as dwarves, ogres, giants, and animal-like creatures, all invisible but so very present on earth, interfere with human beings in an aggressive manner, causing anguish, diseases, and sometimes death. The kagunggurangan (ancestors) demand a lot of attention; they watch over people’s acts and may cause personal trouble and anxiety when they are neglected or forgotten. In Palawan religious and cosmogonic thought, it is the good behavior of the people that creates and maintains order, balance, and harmony in the world.

During a curing session for the sick and tambilaw, a major ritual to cure the whole world, a balyan mediates. He will attempt to connect the queries and hopes of human beings to protective deities such as Ampu, the ancestors, and the good doers, as well as the invisible evil doers in order to reach an agreement. Tingkag (calls) and various urangin (invocations) help the people to overcome their anguish and, with the aid of medicinal plants, to cure their sick relatives and friends. These calls and invocations also help them deal with major natural phenomena and the various masters ruling over these. In highland culture, the karuduwa (a shaman’s soul-double) embarks on a voyage called ulit, a delicate experience guided by his clairvoyance and courage. The shaman has to evolve as he traverses the various realms and discusses with each invisible being, adopting the accurate speech style and voice—either the lumbago, a chanted, pleasant dialogue with the lapis (tutelary spirits), or the bulikata (inverted speech), the way to address the malevolent spirits in their own style.

The shaman has to master various types of invocations, such as the ampang at kagunggurangan (address to to the ancestors); ampang at kamamatayan (address to the dead); and gayat at lapis (invitation to the protective souls).

Various stylized forms of address are used when curing with medicinal plants only: tagtag (magic formula); tagtag at siring (imitative magic formula); baras at ubat (words addressed to the medicinal plant); ampang at kayu (address to the tree); ampang at maraat nang taw (address to a malevolent one); sumpa (vow); nangnang (evil spell); and batya, a magic spell against war, snake bites, and poisons but also for eloquence; and pugay, a “filter” for love.

Tawar is a magic spell cast by a diwata (deity). It is transmitted by a dream from father to son, and uncle to nephew, but only a few people know this method of curing. The mananabang (healer) formulates a tawar together with ruruku (basel flower), bangbawang (garlic) or luya (ginger).

In more important rituals, parina (resin) is smoked, providing clairvoyance to the shaman, and gongs are played in order to communicate with Ampu or Ampu at Paray. A tagtag is uttered in an attempt to cure an illness by siring and is characterized by a concise formula marked by an assonance. For instance, in the treatment of a newborn baby’s jaundice, water dyed a dark yellow from the roots of a tupak tree is applied on the infant’s body as the following translated tagtag is uttered:

I apply you by frictionTupak, your designation,He might turn out maroonDon’t cause more imitationSimilar to you, maroon.

The annual celebration of tambilaw at lungsud is held for the fertility of the earth, the harmony of the world, the freedom of rice plants from pests and other diseases, good weather and climate conditions, and the regular alternation of heat and rain. As the oral, ritual performance takes place, a very complex dialogue develops between the shaman and the malevolent ones. With the assistance of Ampu and the invisibles, an earnest negotiation will bring both parties to an agreement. This type of discussion is also used for curing the sick and is composed of a sagina; a tingkag addressing queries alternately to the malevolent and the benevolent ones; and finally, an ungsud, an offering that seals the agreement.

The whole discussion sounds like a bisara and uses the speech style of the mamimisara, who are the experts in thinking and discussing in the material world. These cosmological dialogues are characterized by the courtesy, kindness, and discreet calm characteristic of Palawan culture.

Tambilaw at tabang is a generous sharing of food and rice wine for the restoration of a patient’s health. It is also a very important ritual for restoring balance in nature during the annual cycle. After a prey such as a boar, bird, or fish, has been caught, there are many brief rituals expressing a way of reciprocating such gifts to the benevolent ones. Rituals of birth and death are rather simple and are mainly intended to protect the living during these delicate moments of passage to another realm.

At the end of December, when the last variety of rice has been harvested in the highlands, a ritual feast, tamway at Ampu at Paray (commemoration of the Master of Rice) is celebrated. It closes an annual cycle and opens a new one. It consists of a drinking ceremony of tinapay or tabad (rice wine) among relatives. To the accompaniment of the basal (gong ensemble), a jar is prepared several weeks in advance. It is believed that the Master of Rice will give a stronger and more fragrant beverage in return for the pleasure that the percussion music gives. The wife of the host makes the purad (yeast). The host, who is the master of the jar, makes the rice wine by first pouring water into the jar containing the rice. He adds sugarcane leaves and gives these a quick swirl before letting these float to the surface to keep the mixture down. Bamboo reeds are placed in a standing position in the jar because these will be used as drinking straws later during the drinking ceremony. Everyday at sunset, gongs are played to invite the people. Then the relatives who have contributed rice to the jar will all come together on the day of the drinking ceremony.

That evening, after everyone has entered the keleng benwa, the host proclaims a warning against violent behavior among the guests. Anyone who responds to the violent acts of a drunken person will be fined. The ritual feast begins when portions of plain, cooked rice on leaves are given to the guests if the harvest has been good. The main gift, however, is the tinapay, and the drinking lasts until dawn. The shaman looks for the children’s lost souls and performs the ulit, together with his gimbar (acolyte). As the shaman chants his encounters with the malevolent ones, he reaches in and tastes the jar of Ampu; instantly, the acolyte enters into a trance. Once they are back on earth and fully conscious, the jar is offered to the guests.

As the drinking starts in earnest, karang at siburan (jar songs) are performed. The elegant and moving timpasan, the invocation to the Master of Rice is sung either by the host only, or alternately by the host and one of his guests. It is sung to invite Ampu to watch over the ceremony during the whole night. Then the men take turns singing the old jar songs: kandiri, aridi, sudsud, and the more recent ones, lantigi and yaya. The women sing, too, as they come to the jar in pairs and take a sip of the wine through the bamboo straw. Meanwhile, everyone talks, chews, or smokes in the flickering light of the fragrant salang (resin torches). Because of paribasa and improvised songs, the guests are gradually taken over by togetherness, solidarity, and a shared joy. This ceremony is the time for sangdugu (blood pact), which forever seals the exclusive, affectionate ties between two persons.

Another ceremony is simbug (mead drinking ceremony), which is accompanied by bangkayaw, a moving song addressed to Ampu at Burak (Master of Flowers), who is the object of the celebration.

Palawan Traditional Houses and Community

Palawan habitats vary in the highlands and the lowlands, specifically in the areas of Makagwa-Tamlang and Punang-Iraray on the eastern side of the island, in Quezon on the western side of the island, and farther south in the Ransang and Kubli-Kanipaan areas.

A scattered habitat of small hamlets of five to seven houses, or larger ones—that is, 10 to 15—is found in the highlands; and a scattered habitat with a very large and strongly built meeting house may be seen in the hilly area of Punang and the coastal plain.

Cave mouths and rock shelters in Barangay Ransang are vital dwelling places of the Tau’t Bato when the rains cause floods in the low-lying areas. The ceilings of these caves are replete with food such as snails on damp stones and bats on the cave’s walls and ceilings. The Tau’t Bato position their living quarters near the cave mouths, which have sufficient sunlight and air, and where smoke from their fireplace could easily escape. In these natural shelters are several platforms laid on very tall and intricate bamboo scaffoldings, following the shape of the rock shelter formation. On one platform might be a pile of plates; near their fireplace, their da-tag (sleeping platform); on another, a family’s living area, and so on.

Wood, rattan, and bamboo are the basic raw materials of Palawan architecture. Cogon grass and palm leaves of many kinds are the complementary elements used to cover the roof and make up the walls. No iron, rivets, or nails are used; joints are tightened by ligatures, not fixed. Thus, a Palawan house is a flexible vegetal structure that is perishable; it can be abandoned, for instance, after a death among its residents.

A nuclear family’s house or an individual house is built on posts, made of two bays with one frontal platform for access and an upper platform at the rear. The framework of the roof is made of trusses with a kamagan (beam) and tanga (rafters).The trusses support the purlins, and the roof is thatched with cogon leaves or of diplak (palm leaves). The binubungan (pole ridge of the roof) has to be perpendicular to the upstream-downstream axis.

Agdan, a wooden log with notches, or a bamboo ladder gives access to the porch if the posts are high. The outline is rectangular or square with only one room but on two levels: datag, the main floor, is lower than the sarimbar, the lateral or rear floor. Below the house, between the posts is the sirung. This is a neutral place, a playground for children and animals, and a place where several things can be stored and protected from sun and rain.

The dapugan (hearth) has no definite place, and several can be temporarily in use either on the ground or in a corner of the house. It consists of three rocks forming a triangle and contained within a square frame made of logs.

There is no partition in this type of small house, which measures three to six square meters. The roof and walls are made of seven species of palm leaves and three species of split or woven bamboo. Weatherboards protect this structure from too much rain and too much sun.

The utensils used in daily life are few. Near the house is the lesung (mortar), which has been sculpted from a tree trunk; the lalu (pestle);the nigu (winnowing trays) of various sizes; and the woven baskets without a lid, their sizes varying according to their capacity for containing unhusked or husked rice. The staple food is cooked in a kandiru (pots) hanging from a sagub (rattan string), and in a kawali (large Chinese pan), which is laid on a paga (tray). The water container on the highlands is a large bamboo with two large internodes. Isap (half-sized coconut) serves as a glass; Chinese plates with fish or ax motifs, along with banana leaves, traditionally serve as plates. The cooked rice is served from a luwag (large spoon) carved from wood. Meals are taken on the main floor.

At night the wife opens the biray, mats of parallel rattans tied together with strings. On top of these, they also unfold a second mat of softened pandan leaves, with the most intricately geometrical and colored designs. Handwoven by the Jama Mapun and by the lowland Palawan, these damdam (mats) delineate the igaan (sleeping area) on the sarimbar platform or on the main floor.

Lagkaw or rice granaries are not part of the family’s house but are usually located at the ends of the village or upland near the fields. A rice granary is a hospitable, shaded place under which one can rest. The Palawan can sit there awhile, and women and children take shelter there to chat and play. The basic structure is made up of six strong usuk (posts), each with a circular wooden plate to prevent the rodents from climbing up and destroying the harvest. The framework of the roof is made of trusses with tie beams and rafters. As in the individual houses, the trusses support the purlins. Because the roof is usually covered with thick cogon leaves, a flattened thatch fixed by two horizontal poles reinforces the ridgepole. The external walls are made of strong tree bark in order to protect the rice from humidity, sunlight, and insects. The edges of the roof and the ridge are cut evenly and thus are considered beautiful.

The kupu is the bachelor’s house. With nine very high five-to-six meter posts, this tiny house is remarkable for its extraordinary height—it is a bachelor’s way of signaling that he is ready for marriage. The floor is made of beams that are tied to the posts resting on a notch. A spectacular double-wooden log with notches gives access to a single platform where the bachelor sleeps, cuts his arrows for hunting with his sapukan (blowgun), and smokes alone.

In Kubli-Kanipaan, young maidens have a very charming little pupu, a house on posts linked by a catwalk to their parents’ house. The maligay is also a beautiful little structure decorated with crossed brooms at the edges of the roof and the end of the ridgepole, where the young girls stay, as the long epics say. On the frame of the only door, the young girl is courted by a young boy playing the kusyapi and smoking a cigarette.

The most striking building, however, is keleng benwa, the large meeting house of the local group and its head, the panglima or magurang, the elder. Here the jural discussions are held, conflicts are resolved, marriage discussions and other agreements are settled, and feasts and rituals are celebrated. Made of very strong wooden posts from the malaga tree and dug into the ground, this large structure with trusses is characterized by floor beams supporting joints on which rests the lawasan (main floor) made of bamboo laths tied with rattan. The main feature of this building is the sarimbar, which are the lateral platforms on the four sides where guests can sit or lie down at night.

Two opposite entrances with a lower platform are covered by a secondary porch roof whose edges reach down nearly to the ground and act as protection against sun and rain. These entrances make this longhouse a fresh and windy place. Inside a singleb, a small alcove made by raising a partition of split bamboo, is the place where one or two jars of rice wine, gongs, and some personal effects of the headman are stored. Sometimes he and his wife and children live in the keleng benwa; when they have visitors, the two of them can sleep in this alcove for privacy.

The set of one or two big gongs and a pair of small ringed gongs hang from the beams, while the drum rests on the lateral platform, ready to be played, mainly at sunset and nighttime. Together with the betel-nut boxes and Chinese plates, beautiful, large bladed knives with carved wooden handles make up the pusaka (heirlooms), which will be shared by the siblings, thus enhancing their solidarity.

The keleng benwa is a most pleasant place where people can talk and debate for hours, celebrate large feasts and ceremonies, and listen to tales and epics. Like the individual houses, it has no furniture, no inner partition except the alcove, but is an open space allowing great freedom of movement and providing a pleasant resting place.

Palawan Crafts

For daily use, the Palawan make simple, functional objects made of rattan, wood, bamboo, and leaves. There is no violent contrast of colors but a variation of greens, yellows, and dark browns. Ukir, the geometric motifs, are made by incision and pyrography. The Palawan people do not paint nor do they weave colorful threads. They have no cotton cloth or ikat, in contrast to the Hanunoo of Mindoro or the Tboli of Mindanao, but they do weave rattan, bamboo, and other palm leaves like buri or pandan, depending on local availability.

The technique of tapa making was revived during the Japanese Occupation. It consists of beating up the bark of a tree to make a baag (G-string for men) and a piece of cloth for the women’s tapis (skirt). However, cloth as well as iron, brass, and chinaware was acquired by the Palawan through trade with seafaring people—a centuries-old tradition. Today, they can buy these goods at the tatabuan (makeshift markets) on the foothills or at the larger ones in the towns of Brooke’s Point, Rizal, Quezon, Narra, Aborlan, and Puerto Princesa, also known as Punta.

Fashion varies according to subgroup, and in the Punang-Iraray and the Kalang Danum areas, it culminates in ornamentation and glamour. The sigpit, with rectangular sleeves and enhanced with shells and/or sequins, complements the tapis. Those worn in the highlands have colorful squares, while the groups on the coastal plain and the seashore prefer the sulindang, which has printed batik with flower and bird motifs.

The men create from hard materials—that is, iron, wood, and bamboo tubes—while the women work on flexible materials such as leaves, clothes, and food. Woven baskets in the highlands are among the finest in the archipelago and are linked to rice cultivation. From July to August, with the first variety of ripening palay in the fields, women weave nigu and baskets of varied sizes such as the sukatan, tabig, and tagtabig, for the coming harvest season.

Men’s artifacts are an offshoot of hunting and the cutting of trees to clear a new field. They make knives and spears with the help of the labungan (Malay forge). They carve the wooden lalu, lesung, and handles for their bolo. Out of the hard, black mantalinaw wood, they may carve luyang, a bracelet for their future wife, and small birds and wild boars as a gift to the Master of Preys in return for a successful hunt. They also carve out of the trunk of a narra tree the long-necked kusyapi and the bangka (outrigger canoe). They have mastered the art of making sapukan and kerbang (quiver) with the internode of a large bamboo, and alap, a double tobacco container. In the Quezon area, they make biray out of seka (rattan), decorate the blowpipe with gitgit (incisions done by wood burning), and make sumbiling (flutes) by piercing tiny bamboo pipes with a hot iron bar. During the dry season, adults and children hold contests for spinning their hand-carved kesing (wooden tops) and flying their bird-shaped taguri (kites).

The Palawan continue to develop their crafts such as basketry and woodcarving, motivated by a growing market for local and foreign tourists, as well as exportation and, to a limited degree, by fair trade marketing groups. The prevalent style of etching blackened wood, or pyrography, is being continued by a new generation of Palawan young men and women artisans such as Wida and Nawilan of Sofronio Española. As traditionally practiced by their elders, they carve human and animal figures on locally available wood from the branches of trees, mindful not to use the trunk so as to preserve the tree. To darken the carved wood, they burn resin from almaciga and use the soot to blacken the object. When the wood is evenly darkened with soot, leaves of plants, such as sweet potato, are wiped over the surface. The wood is again exposed to the smoke to seal the dark color. The darkened wood is decoratively etched and incised to expose the natural light color underneath. The designs are inspired by sea waves, plants, flowers, and leaves; or various geometric designs like spheres, cones, and polygons. These sculptures are representations of animals such as the carabao, local birds, crocodiles, turtles, bearcat, fish, stingray, and squirrels. There are curious human figures called tinao-tao, which are one-of-a-kind male and female figurines, each bearing a unique character such as a fisher, a musician, or a pregnant woman. Aside from decorative sculptures, functional crafts like refrigerator magnets and masks are being designed by artisans. Functional wooden items such as bowls and boxes are etched with designs either at the borders or all over the surface.

|

| Palawan carved wooden images of wild pigs, top (Jojo Orcullo); and tortoise, above, and an unidentified animal, middle (CCP Collections) |

Sculptures by the upland Palawan are three-inch wild boars carved from hard kamagong wood. These are traditionally used as spiritual offerings and as toys for children. Miniature figurines like these wild boars are sold as souvenir items in Palawan. A representation of their god of wind, Kaya’daw, is a two-piece sculpture in which the coccyx of the god figure rests on the fulcrum of a stand that permits the figure to sway gently when the wind blows. Juan Napat from Tumarbong, Quezon municipality is a carver who makes this deity figure.

A popular Palawan basket that has been promoted as a symbol of Palawan ingenuity is the tingkep, fashioned from bamboo, palm, and rattan.The bamboo strips, which may either be in their natural color or darkened, are woven to form interesting patterns. The tingkep are produced in varying sizes. The bigger ones are beautifully adorned with woodcarvings of animals, plants, or human figures. The miniature version, with a brim only three inches in diameter, is more expensive because it is hard to make. It has found its way in the international market as a collector’s item and as a jewelry container for deep-sea pearls. The basket is the subject of a book, The Tingkep and Other Crafts of the Palawan, 2008, which focuses on the tingkep artisans of Amas and Ransang, and on the basket as a symbol of the crusade to preserve Palawan culture, the forest, and the natural environment.

Palawan Indigenous People Literary Arts

There are pleasant evenings when all the kanakan (children) gather in a house and frolic with the adolescents and adults. Palawan children enjoy a lot of freedom going from house to house at night in search of delicacies such as a pigeon, entertainment, and fun. Some evenings they spend answering igum (riddles), a game compelling one to think and reply as quickly as possible.

Igum ni Upu samula:Duwang rajaKasdang lakbangAnu atin?(Atin lungsud.)(Grandfather’s riddle begins:Two platesSame diameter wideWhat is this?[This is the world.])Igum ni Upu samula:Kaya magbaras babaatey yamagbarasAnu atin?(Atin kusyapi.)(Grandfather’s riddle starts:His mouth does not speakHis heart does.What is it?[This is the lute.])

Igum refer to natural objects and phenomena, parts of the body, plants, animals, elements of matter, objects and tools, musical instruments, and more abstract notions like the soul or a myth.

After the fixed opening formula comes a brief and concise composition based on parallelism and symmetry, an utterance made up of two sentences of four words (2 x 2), expanding to six (3 x 2) and including a verb, followed by a question mark. The answer consists of a single word.

In the Palawan highlands, etiological myths are called tuturan et kegunggurangan (teaching of the ancestors), derived from tuturan turu, “to pinpoint,” “to show,” “to teach,” “to give news,” or “to impart information.” It consists of stock information and experience, traditional knowledge transmitted from generation to generation to explain natural phenomena like a mountain range, sea water, the wind, stars, the sun, and the moon; the origin of man, plants, and animals, including birds and insects; and the complexity of a cosmology and a demonology.

In this oral tradition, there are a few major sets of myths with many variants sharing different semantic components such as the myth of the creation of the world, the origin of rice and tubers, the drought, the flood, the seven Thunder Brothers, and the geographical metamorphosis of the hero Tambug and his wife Bihang. Very few relate to a social, religious, or cultural rule, except those prohibiting incest. Palawan myths are concise and organized into a short narration, for they aim to inform, and the literary form of such a teaching is simple and straightforward. The opening formula “Once upon a time, the ancestors said ...” is not compulsory, and the closing formula is rather abrupt: “That’s all, that is the end.”

The audience is always attentive and relaxed. The narration of a myth helps to understand in an implicit way certain magico-religious practices, for mythological knowledge provides the highlanders with a peculiar worldview underlying specific rituals, most particularly the shamanic voyage.

A narrative in a spoken, non-chanted form is called arut in the Punang-Iraray area and usul in the Quezon area. Usul also means “tradition” and refers to any ancient knowledge. In a society with an oral tradition, all narratives are transmitted orally and considered as teaching of the ancestors.

Sudsugid refers to fictional stories or tales whose aim is to remind the people of adat, or good behavior, to teach people the art of relating to and living harmoniously with one another. The tales reveal human failures, mistakes, and misbehavior; they convey an implicit or explicit moral. While myths never end with a moral statement, tales do teach the adat in a playful, humorous, and entertaining manner. From childhood, the Palawan are trained to tell stories and as they perform among themselves, some children can become talented storytellers.

An example of a sudsugid is the myth of Sun and Moon, here in summary: After Ampu had created the world, he created two Aldaw, a male sun and a female sun. He set both suns in motion, the male sun moving ahead of the female one. The male sun’s heat was too intense but the female sun’s heat was just right. Worried that the male sun would kill the plants, Ampu plunged it into the sea, which began to bubble like boiling water in a cauldron. When Ampu took the male sun out of the water, it no longer glowed with heat, though it still gave off light. He named it “Moon.” Hence, the female sun has remained the same, and the male sun is the moon, which first appears small then grows to full size and dies.

The narration of the sudsugid can be brief or may last several nights. Many cunning and hilarious animals teach the people how to work, share, be happy in marriage, trade, cure, eat, and behave in this society according to its moral code based on bagi (sharing), tabang, and ganti. The stories have such characters as a muddy datu, a scorpion datu, a porcupine, two land snails, a good brother-in-law and a bad brother-in-law, three sons of a raja, a rich merchant named Sawragar, a monkey and a civet, and a quail and an owl.

The vocal gesture of a master storyteller reaches the boundary of speech and chant, and the narration flows in a melodic curve with a periodic, repetitive, expected motion. The narrator shifts from a free intonation to a stylized, measured, and tonal quality. The Palawan believe that all narratives are the teaching of an ancestor.

Parallel to the narrative tradition in prose and spoken dialogue is a wealth of long, sung narratives that relate the valorous deeds and ordeals of a hero or a heroic couple. The plot builds up to a crisis manifested by a fight, a conflict, or a war; it comes to a close with its resolution. A fresco, a mosaic of Palawan society, is depicted: nature, social institutions, and socio-cosmic views as well as the history of manners and customs of Palawan culture.

In the highlands, tultul (epics) are sung to honor a visitor; to entertain the guests on the eve of a marriage and its jural discussion; to thank the Master of Prey, Si Lali, after a successful hunt in the forest; or to appease the Master of Game, whose animal has just been caught. A shaman and singer of tales such as Usuy, the chanter of the epic Kudaman, may still be remembered and admired long after he has passed on because of the density of his repertoire, the quality of his voice—that is, the timber and breathing capacity—his melodic lines, ornamentations, and the clarity of his emplotment.

In 1993, Panglima Masino Intaray of Makagwa Valley, Brooke’s Point, became Gawad Manglilikha ng Bayan. His repertoire of tultul, which consisted of epics, origin myths, and stories of Palawan ancestors, included Tyaw, Mamiminbin, Kaswakan, Ka’islam-islaman, and Datu at Lumalayag. By the time of his death at the age of 70 in 2013, Masino Intaray had achieved the recognition and transmission of Palawan art through the basal and kulilal ensemble, as well as of the bagit, the aruding, and the babarak of Makagwa Valley.

Among the highlanders, the ancient form of courting is called lantigi. On the other hand, the people of Kulbi-Kanipaan area on the west coast have the custom of sulag (courtship), usually conducted between a boy and a girl at the tiny doorway of the girl’s pupu. Here, her suitors come and play the lute or the ring flute; they alternately sing geni-geni (love songs) in the old styles such as ginadeng, kesumba, or tigeman; or in inding, the modern style. As of 2003, this custom still exists.

On the foothills, karang at kulilal are a more recent form of sung poems on adultery. A karang is a composition of two couplets making up a stanza. The four lines are characterized by a fixed heptasyllabic meter, rhymes, and assonances. The originality of these sung poems is due to the language itself as well as to the metrical form that regulates it. Many borrowings from neighboring languages—Tagalog, Tausug, and Sinama—are a genuine feature of this poetic language so that veiled messages can be sent.

Passion is measured by numerous opposing poles, a microcosm of feelings shaping a kaleidoscope whose shimmering lights turn around: love-death, fleetingness-constancy, elopement-retraction, invitation-rejection, pleasure-pain, desire-obstacles to desire, and possession-resistance.

Some songs are a way of communicating within the context of a forbidden love:

Kapal tumilatakitut bulan sumilaksapantun pandak-pandakunuhun ku unuhunhindi kita gunahunmama’an lisak dalanlimpakan kung linduanatay ku mangan-manganpikpik papikatansilay tanduk lumisangitut bulan sumimbangbingayan gila dupangdagat manilatakbabai pandak-pandakpantun bulak-bulak.(Far is the boat I ride onThe moon shineslike tiny pandak flowerWhat shall I do, what shall I do?I really do not want you!By the areca palm on the traila signal I plantedMy heart is hungry.Tiny grass, tiny grassHer friends are known and famousThe moon that shinesIs driving me crazy.The wave of the rumbling seathe maiden pandak-pandaklooks like a tiny flower.)

Palawan Indigenous Musical Instruments and Songs

Hunting with a blowpipe and living in or by the dense tropical forest have tended to intensify the Palawan’s receptivity toward sound and to stimulate an inclination towards language creativity, poetry, and music. The Palawan lexicon is very rich in onomatopoeic words. The people often imitate the soundscape around them: bird songs, the sounds of insects, the wind, rain, the earth, fire, and human beings and their tools and musical instruments. Laplap bagit (bird touch or bird scale) is a musical scale reserved exclusively for the imitation of the sounds of nature.

The lute played inbagit music has a pair of dalas or kawat (strings): the melody string called the saningan (from saning, “the acute”), which has six frets on which six pitches may be produced; and the drone string called the lambagan (from lambag, “the low sound”), which has no fret and produces only one sound—an ostinato. Most parts of the instrument are named after body parts: ulu (head); dabdab (chest); duru (breasts); utin (penis); balibang (hips); and ipus (tail), on which sits the instrument when it is laid on the ground or on the floor of the house. The tawil (long neck) is linked to the ruwang (resonant box) by the talinga (ear). The tanglab (lid underneath the box) is perforated with holes shaped into rectangles, crescent moon, and stars.

The melody string rests on a bridge called upu (grandfather), which stands higher than the six frets of this lute. The tubag katan is the sound obtained by plucking the ostinato string and the melody string without pressing; it is the basis for tuning the other pitches of the bagit scale. These pitches are determined by pressing on frets that are glued with kalulut (beeswax) to their exact but mobile places on the melody string. The laplap (touch) on the strings is achieved by the position of the fingers and the manner of playing.

Pagang, the multi-stringed bamboo zither found in Palawan, is also played in the Moluccas, New Guinea, Borneo, Sumatra, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Malaysia, and Madagascar.

Babarak (tiny ring flute) has a scale distinct from that of suling (banded flute). It is played exclusively for the bird scale. The ring may be made of another bamboo tube, a leaf, or a piece of rattan. The system of placement of stops is important, for the theory of making scales is based on this system. Ring flutes in Palawan, Mindanao, and other parts of Southeast Asia use one segment of a bamboo tube with a narrow bore. The segments may vary in length, but the system of placement of stops adapts to these lengths. Usually there are four-plus-one stops—three on one side of the tube, and one on the other side.

Ring flutes of the Palawan and Mindanao groups are vertical, differing from the horizontal ones found among the Tagbanwa and Cuyunon of Palawan, as well as among the Hanunoo and Buhid of Mindoro. On the ring flute, the first stop is bored midway along the length of the tube. Theoretically, this stop represents the octave of the fundamental. However, in many instances, the sound is short of an octave because the hole is bored not exactly at mid length, and compensation must be calculated for the open end of the tube. Once the middle hole is bored, the distance of the other holes, which are usually three, is measured from this first hole by the width of two or three fingers, the palm of the hand, or the circumferential length of the tube. Any of these methods of measuring stops has been repeated from generation to generation, producing the desired intervals of tones in a descending scale, with about the fourth as the lowest interval, and the other two intervals between this fourth and the octave of the fundamental varying in accordance with the above-mentioned measurements from the middle stop.

The aruding (mouth harp) is a delicate percussion instrument of bamboo, known by different names in Mindanao, Sulu, Luzon, and parts of Malaysia, Indonesia, and continental Southeast Asia. The aruding is a type of mouth harp made of bamboo and is plucked with a finger while placed before the open mouth by the opposite hand. It is not pulled by a string as is the case in Java, Bali, and Lombok. The sounds approximate the friction of a vine stirring in the wind, the buzzing of the hard outer wings of the linggawung (palm weevil), or the cooing of doves. This instrument has a tenuous, delicate sound and is played with repetitive rhythmic formulas by men and often by women.

Suspended gongs with a boss played in the Palawan highlands and the Punang area are an important example of music based on rhythm and color. It is distinct from the music of the kulintang or kulintangan, which are suspended gongs that are played in a row, found on the western coast and islands on the West Philippine Sea, south of Quezon, as well as in the Sulu and Tawi-Tawi archipelagos. In the kulintangan, the suspended gongs support the kulintang melody, whereas the Palawan’s suspended gongs are freer to associate themselves with different instruments and to combine different rhythms. For example, the sanang (a pair of suspended small gongs) may be played together with a gimbal (drum) and a big agung (gong).