Subanon (Subanen) Tribe of Zamboanga Peninsula: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Mindanao Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group]

The Subanon are indigenous cultural communities scattered all throughout the Zamboanga peninsula, which was originally named Sibuguey and is located in West Mindanao. The term “Subanon” comes from the root word suba, which means “river.” The suffix nun, non, or nen indicates a locality or place of origin. Thus, Subanon means “those who live along riverbanks and coastal areas.” However, they have become dispersed, having retreated into marginal, less productive mountainous areas. Outsiders call them Subano, Subanu, Suban-on, or Suban-un, depending on their accent. In publications, they are called Subanon, Subanun, or Subanen. Linguists use the spelling “Subanen” because it is phonetically close to the way the native speakers pronounce their ethnic name.

Blumentritt mentioned the Subanon in his accounts, referring to them as “a heathen people of Malay extraction who occupy the entire peninsula of Sibuguey (West Mindanao) with the exception of a single strip on the south coast” (cited in Finley and Churchill 1913). Finley and Churchill, recording their impressions of the Subanon at the beginning of American occupation of southern Philippines in the 1900s, cited published records of early Spanish chroniclers, notably the writings of Father Francisco Combes in 1667, to argue that the Subanon were the aborigines of western Mindanao.

The language of this group is generally referred to as Subanon. However, there are dialectal variations, depending on the locality in which the people live. Using geographical references, scholars in 1900 identified four subgroups of the Subanon: the residents in and around Mount Malindang, Sindangan, Sibuguey, and Siocon. They were considered to be distinct from each other because of the differences in their language and customs. More recent studies of them indicate that there are six subgroups of Subanon: the Sindangan Subanon (Central Subanon), Guinselugnen (Eastern Subanon), Tuboy Subanon (Northern Subanon), Lapuyan or Margosatubig (Southern Subanon), Kolibugan (Kolibugan Subanon), and Siocon (Western Subanon). These groups are dispersed over a wide area of the Zamboanga peninsula.

In 1912, the Subanon were officially estimated to number 47,164. By 1988, their population had grown to about 300,000. In 2010, the Subanon’s population count in the Zamboanga Peninsula was estimated to be 867,012. The Zamboanga peninsula, which is more than 200 kilometers long and shaped like a giant crooked finger that extends westward to the Sulu Sea, is joined to the Mindanao mainland by a narrow strip of land, the isthmus of Tukuran, which separates the bays of Iligan and Illana. Beyond this and to the east is the main region of Muslim Mindanao, which is made up of Lanao del Sur, Lanao del Norte, Maguindanao, Sultan Kudarat, and North and South Cotabato. The peninsula itself is divided into three provinces: Zamboanga del Norte, Zamboanga del Sur, and Misamis Occidental. In Misamis Occidental, the Subanon communities are concentrated along the mountainous provincial boundary that separates this province from the two others.

While practically the whole of Zamboanga has always been the ancestral domain of the Subanon, some areas of the peninsula are occupied by Muslims and a few others by Christian settlers. The entire southern coastal region of Zamboanga del Sur, from the Basilan Strait to Pagadian near Lanao, are populated by mixed Muslim groups. Major urban concentrations such as Zamboanga City, Pagadian, and Dipolog have a sizeable number of Christians.

History of the Subanon Tribe

Before the arrival of Islam and Christian missionaries, the Subanon occupied the entire Zamboanga peninsula, sharing it with the Negrito who, since then, have disappeared from the whole region.

|

| Subanon woman and child (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

It is believed that the earliest traders who came in contact with the Subanon groups were the Arabs. The Arabs came first to trade, then to do missionary work, and finally to establish a political base. Their coming and the subsequent establishment of Islam in Southern Mindanao occurred from about the 9th to the 15th centuries. In the latter part of this period, the Sultanate of Sulu was established, and its political dominance extended across the Zamboanga Peninsula.

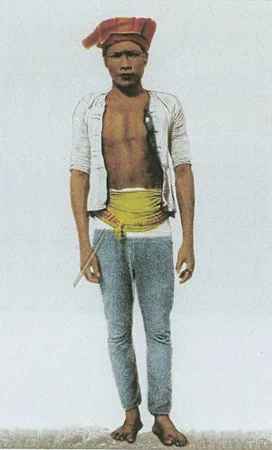

|

| Subanon man (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

For some time before the Spaniards came and during the period of colonial rule, the Subanon had contact with the Tausug and the Maranao. This relationship was not entirely commercial. To a large extent, it was one of domination by a powerful group over a weaker one since the Muslims often invaded Subanon territory for the purpose of capturing slaves and exacting tribute. The Muslims not only controlled coastal trade but also extracted dues or tithes from the subjugated Subanon.

The coming of Spain to the Philippines as a colonial power complicated the picture. The Spanish colonial government sought to extend its sovereignty over the whole of southern Philippines. Declaring its intention to “protect” the non-Christianized, non-Muslim Subanon of the Sibuguey, the government, under General Weyler, constructed a series of fortifications across the Tukuran isthmus “for the purpose of shutting out the Malanao Moros from the Subano country, and preventing further destructive raids upon the peaceful and industrious peasants of these hills” (Finley and Churchill 1913, 4).

In 1870, the Spanish colonial government established the San Ramon prison and penal farm at the southern tip of the peninsula. It was 25 kilometers north of the Spanish principal settlement, which is now present-day Zamboanga City. Its neighboring towns were Ayala, which had a population of 2,000 baptized Subanon; Busugan, with 120 Yakan; and Reus, with 500 Subanon. Criminals with life sentences were sent to this penal farm, which was a rectangular area five kilometers long and three kilometers wide.

Spanish control of its garrisons and fortifications like Tukuran and Fort Pilar, and of institutions like the San Ramon prison, ended in 1899 under the terms of the Treaty of Paris. Before the American government could bring in its occupation troops, however, the Muslims from the lake region crossed the isthmus and attacked the Subanon in the two districts of Zamboanga and Misamis. These renewed raids took their toll on lives and property, with many Subanon being carried off into bondage by the invaders. The military garrison was taken over by Muslim forces, and a kota (fort) and several villages were established on the isthmus. The place was abandoned, however, when the American expeditionary forces appeared in October 1900.

Despite the long history of hostile actions against them by their culturally assertive neighbors, the Subanon have managed to preserve their tribal unity and identity, their language and dialects, their customs and traditions, and their religious worldview. While feats of bravery are recounted in their ancient stories, the Subanon do not have an organized army of warriors. Feeding and maintaining full-time warriors require food surplus, which is not possible under the kaingin (swidden or shifting farming) system, their main system of food production. Their relatively egalitarian society also resists extensive political organization. When confronted with a more aggressive military force, retreating into the less accessible interior of the mountain has been the Subanon’s adaptive form of defense.

Since the beginning of the present century, the Subanon’s contact with the outside world has broadened to include the Visayan and the latter-day Chinese. Aside from the influx of these settlers and traders, there has been a massive penetration of the national government into the Subanon hinterlands for purposes of administrative control, tax assessment and collection, and police enforcement of national law.

The idyllic interior forest and mountain haven into which generations of Subanon have been driven deeper for several periods hardly exists at present. By 1991, wide swaths of primary forests had been cut by Manila-based logging concessions. Since the mid-1990s, organizations of various Subanon groups have petitioned national agencies concerned with environmental and tribal issues to protect the threatened homeland of this lumad group. It is a problem faced not only by the Subanon but by practically all the indigenous people of the island of Mindanao.

Livelihood of the Subanon People

The Subanon meet their daily needs primarily through agriculture. Along the coastal area, wet agriculture cultivation using a carabao-drawn plow is the method of producing the staple rice. On rain-fed dry lands, the Subanon grow corn, coconuts, hemp, squash, eggplant, melons, bananas, papayas, pineapples, jackfruit, and lanzones.

|

| Subanon farmers harvesting rice (Charlie Saceda, photo courtesy of Jet Hofer) |

Based on their native methods of meteorology, the Subanon identify three distinct seasons within the agricultural cycle: pendupi, from June to December, characterized by winds blowing from the southwest; miyan, from December to January, a time of winds and northeast monsoon rains; and pemeres, from March to April, the hot and dry season.

Between the coasts and the uplands, the Subanon practice both wet and dry agriculture. In the hilly uplands, kaingin farming is the most common form of cultivation.

Shifting cultivation has five well-defined general stages: site selection, cutting, burning, cropping, and fallowing. Site selection usually starts after the harvesting of the crops of the previous year’s cropping season and continues until the end of the rainy season, from August to December. During this period, the Subanon go into the forest to gather honey; rattan canes for weaving baskets; ornamental plants; sago; buri; lumbia or lumbay, which are palm types with the pith along the entire length that is a rich source of starchy flour; as well as several varieties of wild edible roots. As they roam the forest to gather these products, they also keep an eye out for their next swidden site. The soil type, terrain, and the distance from the settlement are all important considerations for their choice. After the physical examination of a proposed site, a ritual follows which formally marks the occupancy of the site.

Cutting has two phases. The first phase is the slashing of small trees and undergrowth. It takes place at the end of December to January. Slashing may be done by both men and women, with the use of the bolo. The second phase is the cutting of big trees. It occurs at the end of January to the beginning of March. The task of felling large buttressed trees is the sole job of men. It requires one to build a scaffold about two or four meters above the ground.

When the felling of big trees is completed, the tree leaves and grass are left to dry for burning later. Burning must be done just before the rains come. Determining the exact day of burning requires an understanding of the relationship between natural phenomena and the agricultural cycle, and the ability to interpret the signs of nature such as wind patterns, cloud formations, constellations, and even the sounds of crickets and of other animals in the jungle.

The cropping stage consists of planting, tending, and harvesting crops such as several varieties of upland rice, corn, sweet potatoes, cassava, gabi (taro), ubi (yam), and vegetables. After two or three cropping seasons, the cultivators go in search of another virgin or secondary-growth forest. Shifting to another field allows the field previously used to replenish its natural vegetation and recover its soil fertility. When the soil has fully recovered its fertility, it may be cleared again for swidden.

The Subanon supplement their income and food supply by hunting and trapping wild animals, gathering forest products, and fishing. This is not only to supplement their protein intake but also to protect their swidden farms from wild fowl, wild pigs, deer, and monkeys. Animals are captured with the use of a slip noose, a trapping cage, a sharp bamboo projectile called balatik, or with the help of dogs to drive them toward a place with trapping net or pits planted with suyak or bamboo stakes.

Balatik consists of a spring made from a strong but pliant sapling, razor-sharp projectile, and a triggering device. The bigger end of the sapling is fastened to a stump or the trunk of a small tree, while the other extremity is bent and locked to a triggering device, which includes a strong wild vine tied across the trail. The handle of the projectile is attached to one end of the spring; its sharp end is aimed at the prey’s vital organs, such as the heart or lung.

The Subanon engage in freshwater fishing by means of a variety of traps, four-pronged spears, spear guns, and organic poisoning. Fish traps are most commonly used by the Subanon to catch fish. These are placed in the lake or against the current of the water in a stream. Those placed in the lake must contain bait, usually cooked tubers or coconut meat, in order to attract crabs, shrimps, and fish. But traps that are placed against the current of the water in streams need not contain any bait. The fish, carried by the current, are easily trapped.

During the dry months, the Subanon catch fish by using roots or vines of poisonous plants. The roots are pounded on the rock and then squeezed in the running water of the river. The mild poison will make the fish dizzy and float on the water, making it easier for the fishers to pick them with bare hands. When poisonous plants are not available, fishers will divert the flow of the main stream by placing obstructions in its passage.

The extra rice and corn the Subanon produce, plus the wax, resin, and rattan they gather from the forest, are brought to the towns and traded for cloth, blades, axes, betel boxes, ornaments, Chinese jars, porcelain, and gongs.

Subanon Community

The neighborhood, called sumbalay by the Guinselugnen or Eastern Subanon, is the basic independent political unit. It is composed of karumanan (individuals related by blood or marriage) and outsiders who live with them peacefully. The sumbalay is headed by the most senior male member of the community, who is called timuay in the western part of the Zamboanga peninsula or gukom in the eastern part. Timuay, variously spelled as timuai, timuway, and timway, is a Maguindanao word that means “chief” or “leader.” The word “gukom” seems to be a variant of the Tagalog and Cebuano term hukom, which means “judge” or “arbiter.” Timuay or gukom connotes both civil and religious authority for the bearer of the title. A chief headman among the Guinselugnen is called gungal gukom. He is considered as a basalag gataw (big man) by virtue of his wisdom, wealth, and other abilities that ordinary men do not possess. He is highly esteemed and respected in the community and noted to be a man of respect and humility.

|

| Subanon elders (Raisa May Fernandez) |

The title of timuay or gukom may be recalled by the community and given to another tasked with the responsibility of leading the community. The timuay invokes this authority in cases of violations of social norms such as affronts or insults, violations of contracts, and other offenses. Under his leadership, an association or confederation of families forms a community. If the timuay proves to be an efficient and popular leader, the community of families under his authority may expand. The authority of the timuay does not correspond to a particular territory. Within the same area, his authority may expand or decrease, depending on the number of families that put themselves under his authority. Consequently, “when a family becomes dissatisfied with the conduct and control of the chief, the father secedes and places his family under the domination of some other timuay” (Finley and Churchill 1913, 25). This, then, is the basis of Subanon patriarchal society: the absolute authority of the father to assert the supremacy of family rights within a community voluntarily organized under a designated timuay.

During the Spanish and American periods, there were several attempts to organize the Subanon into politically administered towns or villages, but these attempts were resisted by the people. Such was the premium the Subanon put on individual and collective freedom from external domination. In recent times, the Subanon timuay have been confronted with concerns ranging from local issues affecting their particular community to larger, regional issues confronting the entire Subanon group. These issues include the defense of the Subanon ancestral domain against the encroachments of loggers and mining companies. Highly politicized Subanon leaders have been active in organizing their people and coordinating with nongovernment organizations of tribal advocates. Today, the Subanon political system has been subsumed under the Philippine government’s political system.

Subanon Tribe Culture, Customs and Traditions

Video: Subanen Tribe Documentary

The sumbalay, a neighborhood of a dozen or more households, is a unit of social organization where members engage in frequent interactions. In cases of dispute, members may intervene to mediate so that over time, they may develop as efficient arbitrators of disputes and become recognized as such by their neighborhood. There are many such communities in Subanon society. A bigger group of interacting communities may contain as many as fifty households.

|

| Subanon wedding ceremony, 2009 (Charlie Saceda, courtesy of Jet Hofer) |

The Subanon practice polygyny. They also practice levirate and sororate forms of marriage. In levirate marriage, the woman marries the brother of her dead husband. In sororate marriage, the man marries the sister of his dead wife. These two forms of marriage seem to reaffirm the view that marriage establishes a more or less permanent tie, a tie that even outlives the principal of the marriage.

Selecting a spouse to marry can be done in three ways. First, the family can arrange the marriage, which can take place even before the parties reach the age of puberty. In this type of marriage, the parents select the spouse for their child. Second, a go-between is hired as a spokesman by the boy to express his desire for a lady. Third, conventional, modern courtship is followed, in which the young man and young woman first become friends and then the young man personally expresses his love to the young lady. Whatever method is used in selecting a spouse, the contracting families go through the preliminaries of patching up previous conflicts before determining the bride-price, which may be in the form of cash or goods or a combination of both.

Before the wedding day, the intermediary of the girl’s family notifies the boy’s family that they can come to make their formal proposal of marriage because the girl’s family has been properly informed. When the boy’s family reaches the girl’s house, they are stopped at the head of the stairs before they can enter the house. They must first give a symbolic entrance fee called limilimi. When all have entered the house, the members of the boy’s family are invited to sit along the edge of a sleeping mat, which has been placed on the floor of the main and biggest room of the house. The spokespersons of the boy’s family ask the spokespersons of the girl’s family to take a winnowing basket and an ear of corn. When the winnowing basket arrives, the girl’s party turns it upside down to cover the corn, which has had a few kernels removed from it. A sharp knife is laid on top of the overturned winnowing basket. After these symbolic objects have been placed at the center of the floor mat, discussion of the proposed wedding begins while both parties chew betel nut and smoke tobacco.

During the negotiations called pamalabag, literally “to oppose,” the girl’s spokespersons try to show opposition to the proposal and encourage her other family members to express their opposition to the proposed marriage. If there are any problems from the past or anything that the family of the girl still holds against the boy’s family, the winnowing basket will not be turned right side up until some payment is made. The offended person will receive the payment. The payment ensures that the problem will be forgotten and offenses forgiven.

Once the bride-price is determined, a partial delivery of the articles included in the agreement may be made, to be completed when the actual marriage takes place. After the marriage ceremonies have been held and the wedding feast celebrated, the newlyweds stay in the girl’s household. The man is required to render service to his wife’s parents, mainly in the production of food. After a certain period of matrilocal residence, the couple can select their own place of residence, which is usually determined by proximity to the swidden fields.

Family properties that are covered by inheritance consist mainly of acquired Chinese jars, gongs, jewelry and, in recent times, currency. The ownership of cultivated land, the swidden field, is deemed temporary, because the Subanon family moves from place to place, necessitated by the practice of shifting agriculture. The grains stored in bins or jars do not last long and therefore are not covered by inheritance.

The family as a corporate unit comes to an end through divorce, abduction of the wife, or death of either spouse. But it can be immediately reconstituted through remarriage. The surviving widow can be married to a married or single brother of the deceased husband, or the parents of the deceased wife can marry off to the widower one of their unmarried daughters or nieces.

Socioeconomic needs bring about close relationships in Subanon society. Spouses can expect assistance in many activities from both their parents and their kin, and they in turn extend their help to these relatives when it is needed. Non-relatives are expected to give and receive the same kind of help. By the mere fact that they live in a neighborhood, non-relatives become associates in activities that cannot be done by the head of the family alone such as constructing a house, clearing the field, planting, or holding a feast.

In death, a person is sent off to the spirit world with appropriate rituals. First, the corpse is cleaned and wrapped in white cloth. Then it is laid inside a hollowed-out log and given provisions such as food for its journey. A rooster is killed, its blood smeared on every mourner’s feet to drive away malevolent spirits who may be in attendance. The log-coffin is then covered, and the surviving spouse goes around it seven times and under it another seven times while it is held aloft. Those who accompanied the deceased to its grave, upon their return, get hold of a banana petiole, dip it in ash, and throw it away before they go up their respective houses. Those who carried the coffin take a bath in the river before returning to their houses to wash away any bad luck they may have carried with them.

Each time the widower eats, he leaves a space on the floor or at the table for his dead wife, and invites her to eat with him for three consecutive evenings. He mourns for her until he can hold a kano feast. Before this, he cannot comb his hair, wear colorful clothing, or remarry.

Subanon Religious Beliefs and Practices

The Subanon are firm believers in a supreme being called Gulay. Other terms for Gulay include Apu’ Asug, Gegded, Megbebaya’, and Meglengaw. The Subanon consider him as the creator of heaven and earth, the giver of life, and the creator of the first man and woman.

In place of a hierarchy or pantheon of supreme beings, the Subanon believe in spirits who are part of nature. These spirits inhabit the most striking natural features, which are considered the handiwork of the gods, such as unusually large trees, huge rocks balancing on a small base, peculiarly shaped mounds of earth, isolated caves, and peaks of very tall mountains. However, the favorite abode of the deities in the mountains is the banyan or balete tree.

The numerous deities of the Guinselugnen are classified into three general categories: luminilong, good spirits and guardians of all the deities; mamanua, good spirits but lower in rank than Luminilong; and salot, evil spirits who harm people. Among the Subanon in the western side of the Zamboanga peninsula, the salotis called getautelunan.

The Subanon believe that the self is composed of two parts: the physical body and the gimod or soul. Gimod is the spirit that dwells in the human body and leaves the body once the person is dead. When the person is still alive, the gimod can wander independently from the body and interact with other souls; it can also be captured and prevented from returning to the body. An ailing person’s soul is believed to momentarily depart from the person’s body. It is up to the balian to recall the straying soul and reintegrate it with the ailing person so that the illness could end. If the balian fails, the patient dies. The soul then becomes a spirit.

The balian, as in any traditional shamanistic culture, occupies a very special place in Subanon religious and social life. The balian are believed to be capable of visiting the sky world to attend the great gatherings of the deities known as bichara (assembly or meeting). They are also acknowledged to have the power to raise the dead. Most religious observances are held with the balian presiding. These rites and activities include the clearing of a new plantation, the building of a house, the hunting of the wild hog, the search for wild honey, the sharing of feathered game, the beginning of a journey by water or by land, and the harvesting of crops. The religious ceremonies attending the celebration of the great buklog festival, held to propitiate the diwata (fairy) or to celebrate an event of communal significance, are exclusively performed by the balian. In general, the functions of a balian are those of a medium who directs the living person’s communication with the spirits, a priest who conducts sacrifices and rituals, and a healer of the sick.

The matibug are the closest friends of human beings, but they can be troublesome if ritual offerings of propitiation are not made. These offerings are not expensive. A little bit of rice, some eggs, a piece of meat, betel quids, betel leaves, and areca nuts, given in combinations according to the shaman’s discretion, would suffice to placate the spirits. These offerings can be made inside the house or out in the fields, by the riverbanks, under the trees, and elsewhere. It is believed that the supernaturals partake only of the sengaw (essence) of the offering, and human beings are free to consume the food and wine. The getautelunan can be dangerous; they are demons and must be avoided. Some diwata can also inflict sickness or epidemics. However, deities residing in the sky world are benevolent. In some Subanon subgroups, there is a belief in a Supreme Diwata.

While under the Sultanate of Sulu, circa 14th century, some Subanon became converts to Islam. These converts comprise what is now called Kolibugan Subanon, a subgroup occupying the southern part of the Zamboanga del Norte and Zamboanga Sibuguey provinces, who number around 20,000. But from the late 16th century up to 1769, the Jesuit missionaries worked to Christianize the Subanon. The converted Subanon adopted the Spanish-influenced culture and were assimilated with the present Christian population. They became part of what are now known as the lowlanders. The Subanon who refused to become Christians fled to the inaccessible areas of the mountains. They became the uplanders, whose descendants are the contemporary Subanon population in various mountainous areas of the Zamboanga Peninsula.

Subanon Tribal Houses

The typical Subanon settlement is composed of any number of either clustered or dispersed households and is normally located on high ground close to the swidden farm. There are three types of houses according to purpose and materials used: the tree house, field huts, and permanent dwellings.

|

| Subanon house (Charlie Saceda, photo courtesy of Jet Hofer) |

In times past, the tree house, built atop a 12 foot-high stump, protected the Subanon from enemies, who could not strike with the spear from below. The ladder, made of a notched tree trunk, was pulled up by residents, thus preventing the enemies’ quick and sudden entry.

The Subanon have field huts for temporary shelter. Field huts provide some shade when one is guarding the swidden farm from rodents, monkeys, and wild pigs. However, not all Subanon farmers have field huts. A field hut is resorted to only when one’s permanent dwelling is far from the swidden farm. This is constructed with the use of two poles with forked ends standing vertically from the ground. A small round timber, about three inches in diameter, is placed across each forked end of the two erected poles to make a horizontal beam. Two slant supports are made to lean on the horizontal beam. The slant supports are joined by roofing joists. They are secured to each other at every joint so that they become one strong unit. The roofing of a temporary shelter is made of banana leaves, palm fronds, or the bark of trees.

Permanent dwellings in the settlement vary in sizes and durability. The traditional Subanon house is generally rectangular, thatch-roofed, with a small floor space averaging 12 square meters. Invariably, there is only one room and therefore space for only a single family. In certain areas where contact and acculturation with the settler economy have taken place, some Subanon have begun building houses like those in the lowlands. In the interior parts of the peninsula, however, houses retain the traditional features recorded by ethnographers in the 19th and early 20th century.

The roof of a Subanon house is densely thatched with nipa fronds. The pitch or slope of the roof is fairly steep. The house has no windows, but the overhanging eaves protect the inside from rain. Around the sides of the house, some spaces are thatched with palm leaves, which can be detached at will. In good weather, this portion is opened to let in light, which also comes in through a space between the top of the walls and the roof. Light also enters through the entryway, which seldom has a door, and through the numerous spaces between the floor’s bamboo slats.

A platform or porch in front of the door, usually measuring 2.5 square meters, serves many purposes, such as for husking rice and drying clothes. It also helps keep the house clean, especially in rainy weather, since the occupants scrape mud off their feet on this platform before entering the house. A ladder is necessary to gain access to the living room from the ground. In many cases, this ladder consists only of a log with notches. When the occupants are not home, the log is lifted away from the door and left leaning against a wall of the house. Sometimes there is a smaller log, sometimes two, flanking the notched log, serving as handrail.

The main beams supporting the entire structure vary, depending on the intended length of stay in one area. Most houses are built without the expectation of using them for many years, due to the shifting nature of agricultural work. Houses are built as close as possible to a new field. Occasionally, a site is found so favorable that the house is built to last, employing heavy and solid wooden supports. The strongest houses would have supporting beams made of hardwood 15 to 20 centimeters thick, but this is rather rare. Usually, the supporting timbers are one centimeter thick, the entire structure being so light a person could easily shake it at one of the supports. Tops of supporting beams are connected with rough logs that serve as stringers, to which the split bamboo or palma brava, or other flooring materials, are lashed with rattan strips. No nails are used in putting houses together, and even the use of wooden pegs is rare. Strips of rattan are the most favored fastening material.

The interior of the house contains both the sleeping area and the hearth. The latter, found near the door, ordinarily consists of a shallow, wooden, squarish structure whose bottom is covered with a thick layer of earth or ash. Large stones are put atop the ashes to hold the earthenware pots. There is no ceiling, and the exposed beams of the roof serve as convenient places from which to hang a multitude of things. In the house of a prosperous family, as many as 30 or 40 baskets are suspended from the roof with strips of rattan or abaca. Clothing, ornaments, rice, pepper, squash, corn, drums, guitars, and dishes are some of the things stored in this way. Salt, wrapped in leaves, is also suspended over the hearth so that it will not absorb too much moisture from the atmosphere. Hanging things from the roof beams has two advantages: the articles do not occupy floor space and get in the way, and they are protected from breakage, insects, and rodents.

The small granaries built near the Subanon house are raised some meters above the ground. At times, these are so high a notched log is required to enter the structure. Inside the granary, the rice is stored either in baskets or in bags.

Aside from these granaries and their dwellings, there is a special structure added to the spirit house of a shaman—a miniature house called maligai, which is made to hang from under the eaves. The maligai is where the sacred dishes are kept. On the roof of the spirit house stand carved wooden images of the omen bird limukun.

Subanon Crafts

Unlike the glazed imported jars in some households, the indigenous earthenware of the Subanon are simpler in execution and design. The process of making pots starts with the beating of clay on a wooden board with a wooden pestle. The clay is then shaped into a ball, on top of which a hole is bored. The potter inserts her hand, which holds a smooth stone, into this hole, and proceeds to enlarge the hole by turning the stone round and round the inner surface of the clay. Her other hand holds a small flat stick, with which she shapes and smoothens the outer surface. Having hollowed out the clay piece and finalized its shape, she then puts incisions or ornamental marks on the outside, using her fingers, a pointed stick, or a wooden stamp engraved with a simple design. The pot is made to dry out under the sun, after which it is fired, usually over hot coals. The last step is to strengthen the pot by crushing the slimy leaves of the likway plant and scraping the bark of the lamay bush. The crushed leaves and the bark shavings are rubbed onto the inside walls of the pot and then boiled in it. The baked pot is then ready to hold water or boil rice.

|

| Subanon girl making thread, 2017 (GREAT Women) |

Most Subanon, regardless of age and gender, are expert mat and basket weavers. The materials used for baskets are rattan or bamboo strips or a combination of both. These baskets are used to contain, carry, or store agricultural crops, or to serve as receptacles for religious offerings. This explains why their baskets have little or no decorations.

|

| Subanon basket made of rattan and bamboo strips (Ayala Museum Foundation) |

Since the manufacture and use of baskets are part of their daily activities, they have many indigenous names for baskets. Biaw is the biggest basket, made for transporting unhusked corn or coconut from fields to the homes. Its capacity is about 1.5 cubic meters. It is transported on a sled that is towed by a draft animal such as a carabao.

Baban is second to biaw in size. It is used for carrying different agricultural produce except grains. Its capacity is enough for one person to carry on his shoulder or on his head. Both biaw and baban have an open-weave pattern. A smaller carrying pack, which has a close-weave pattern, is designed for carrying clothes and vegetables.

Storage baskets such as bandi and danas are used for dry food like grains and nuts. The basket may widen from the bottom to the middle part of the body and narrow again toward the rim, especially if it has a cover. However, when there is no cover, it may widen in a gradual slope from bottom to top, with its mouth being the widest.

Niygo, a winnowing tray, has a parallel-close-weave pattern, whereas the gyagan, a sifter tray, has a parallel-open-weave pattern. All these utilitarian baskets are woven by means of twilling, a weaving technique that produces a pattern of diagonal and parallel ribs.

Fish traps like bantak and sanggab, and baskets like the sukat and ginumbuwan, which serve as receptacles for religious offerings, have the twining weaving pattern. In twining, the weaver uses either rigid or flexible warps tied together by flexible wefts.

Cloth weaving is basically similar to the style of the neighboring Muslim region. The weaving loom is set up inside the house. Cotton thread, spun by women using the distaff crafted by men, and abaca fiber are commonly used. Before cotton was introduced by Muslim and Christian traders, the Subanon used abaca fiber for their clothing and blankets. The strands or fibers are first dyed before being put in the loom. In this process, several strands are bound together at intervals by other fibers, forming bands of various widths. Thus tightly bound, these are dipped into the dye then laid out to dry. The effect is that the bound part retains the natural color of the fiber, while the rest has the color of the dye. The process can be repeated to achieve various designs or color combinations. The favorite dye among the Subanon is red, with black also being widely used. Native dyes from natural substances, which give a flat or matte color, and aniline dyes are used in the process.

The finer metalcraft possessed by the Subanon, such as the kris, kampilan (cutlass), barong (bladed weapons), and pes (chopping knives), has been obtained through trade with the Muslims. But the Subanon also produce some of their weapons and implements. They also use steel, especially in making blade edges. The Subanon forge has bamboo bellows, while the anvil is made of wood with an iron piece on top where the hot metal is worked into shape.

Subanon Literary Arts

Everyday activities are reflected in these Central Subanon riddles (Su Gesalan 2002):

|

| “If you try to carry it on your shoulder, you can’t. But if you try to drag it along, you can.” – Subanon riddle about the carabao (Illustration by JC Galag) |

Sa gebii, lelanit.

Sa gendaw, sumpitan. (Gikam)

(At night, it is leaves of the pandanus plant.

In the daytime, it is a blowgun. [Seeping mat])

Sa pisanen mu, ndi mu maban.

Sa biglasen mu, maban mu da. (Kelabaw)

(If you try to carry it on your shoulder, you can’t.

But if you try to drag it along, you can. [Water buffalo])

Speeches at weddings are more poetic than prosaic, such as these exhortations below against infidelity by the groom then the bride (Su Gesalan 2002):

Sa duuni maita mu libun melengas gupia, maita

llumidus dig liigen saba kelengasen, ndi mu

pegbentayay, tagikul mu gusay su sawa mu.

(If you see a very beautiful woman, one so fair

you can see the food going down her throat, don’t

look at her, still concentrate on your wife.)

Bisan mekaita’a begutaw mekpanit bulawan,

mpuli’i pengengleng mu saba lengasanen, ndi

mu pegbentayay, segaga tagikul mu guisay laki

mu kiin.

(Even if you see a young man with skin of gold,

so handsome that your gaze returns to him, don’t

look at him but instead concentrate on your

husband.)

There are blessings, such as the following, given for a person’s healthy and long life:

Menitaya dig daun tebu, mengingusa daun

padang, mektepala taud binangan. Kebal kaiben

mu dig benwa keni, naa meliida pa di gulen.

(May you be agile enough to walk along a

sugarcane leaf, and to walk to the tip of a blade of

cogon grass and to step from the top of one tall

braced tree stump to another. You will be in this

life so long that you will even lie curled around an

earthen rice pot.)

Another blessing is for longevity (Su Gesalan 2002):

Ya’a pelum, saba kepia kulis mu, kebal kaiben

mu dig benwa, mengekdaka pa di gatun,

mengindaapa di pekegaun.

(May you remain long on this earth, so long that

you will wash clothes on the floor beams of the

house, and go fishing on the kitchen fire table.)

The use of the names of rivers, streams, and mountains is an organic and prominent element in many Subanon poems (Su Gesalan 2002):

Dipelanung, yayawanen

Salug, lai kunglatanen.

Madanding, kemedanen

Suminugud, egludenen.

Sibugay, pengnaapnaap

Danaw, pekegyugegyug.

(As if in flight, with view from sky to sky

At Salug, we stared wide-eyed in wonder.

At the Maranding River, there was whispering

The Suminugud River became a place to hide.

The Sibuguey River splashed as it rose and fell

While on the mountaintop, Danaw shock and shook.)

Four Subanon epics have been recorded and published: Guman of Dumalinao, Ag Tobig nog Keboklagan (The Kingdom of Keboklagan), Ag Pematay nog Getaw (The Death of Man), and Keg Sumba neg Sandayo (The Tale of Sandayo). All are performed during the weeklong buklog (ritual dances). Guman contains 4,062 verses; Keboklagan, 7,590; Pematay, 8,529; and Sandayo, 6,577.

|

| Sandayo at the center of the sun, with his monsala or magical scarf (Illustration by JC Galag) |

The epics feature the diwata, as well as mythical and legendary heroes and chieftains who are partly divine. These tales pass from one settlement to another during festivals and are well-known among both the Subanon and the Kalibugan in both northern and southern parts of the Zamboanga peninsula. Composed of many stories, these epics are told in a leisurely fashion so that it takes one night to complete a story. The chanters of the epic, men or women, have to have a strong memory and a good voice. They are honored and respected by the community, since they possess valuable knowledge of well-loved mythic events, which they recount in a most entertaining manner. They are aided by “assistants,” who encourage and sustain them, and start off the epic by chanting a number of meaningless syllables, giving the bards the pitch and duration of the recitative. Whenever they think the bards are getting tired, the assistants give them a chance to rest by taking up the last sung phrase and repeating it, sometimes twice.

The Guman from Dumalinao, Zamboanga del Sur has 11 episodes that narrate the conflict between the good, represented by the parents, and the evil, represented by three evil queens, their descendants, and other invaders. The monumental battles are fought between these forces in order to capture the kingdoms of Dliyagan and Paktologon. In the end, the forces of good, aided by magical kerchiefs, rings, birds, and swords, conquer the evil powers.

The Keboklagan of Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte is a saga about the life and exploits of the superhuman hero named Taake from the kingdom of Sirangan. His successful courtship of the Lady Pintawan in the kingdom of Keboklagan in the very navel of the sea sets off a series of wars between Sirangan and other kingdoms, led by chieftains who resent a Subanon’s winning the love of the lady of Keboklagan. The wars spread, dragging other kingdoms into the fray. The chiefs of Sirangan, led by Taake, overpower the other chiefs, but by this time, there have been too many deaths, and Asog the Supreme Being in the sky world is bothered by this. Asog descends to earth and tells the combatants to stop fighting and to hold a buklog, during which each of the warriors will be given a life partner. He fans the kingdoms, and all those who died in the fighting spring back to life.

The Pematay nog Getaw, also from Sindangan, Zamboanga del Norte, was chanted by Liyos, an 80-year-old epic chanter. The epic tells the story of Benobong Sapendangan and Daqog Bulawan. On her journey to the kingdom of Bulawan, Sapendangan loses her way and comes upon the kingdom of Sindepan, which is ruled by Panday Rirok. Sapendangan and Panday Rirok live together until Mendig Pesa, in the form of a tongilaw bird, abducts Sapendangan and takes her to the kingdom of Bulawan. The people of Bulawan disapprove of Mendig Pesa’s deed, and they order the return of Sapendangan to Panday Rirok. On their way back to Sindepan, Mendig Pesa and Sapendangan engage in a number of battles. But with the help of Daqog Bulawan and their datu relatives, they are able to kill their enemies. During a buklog, Daqog Bulawan marries Sapendangan, and the other datu and ladies follow suit. Bulawan then gives advice to all the people and mentions that he misses his father, Pon Benowa. After this, Bulawan and Sapendangan suddenly expire on their seats.

The Sandayo of Pawan, Zamboanga del Sur narrates in about 47 songs the heroic adventures of Sandayo. Sandayo is brought to the center of the sun by his monsala (scarf). While in the sun, he dreams about two beautiful ladies named Bolak Sonday and Benobong. He shows his affection for Bolak Sonday by accepting her mama or betel nut chew. At the buklog of Lumanay, Sandayo meets the two ladies. Here he also discovers that Domondianay, his opponent in a battle that had lasted for two years, is actually his twin brother. After a reunion with his family at Liyasan, Sandayo is requested by his father to aid his cousins, Daugbolawan and Lomelok, in producing the dowry needed to marry Bolak Sonday and Benobong. Using his magic, Sandayo produces the dowry composed of money, gongs, jars “as many as the grains of one ganta of dawa or millet,” a golden bridge “as thin as a strand of hair” that would span the distance from the house of the suitor to the room of Bolak Sonday, and a golden trough “that would connect the sun with her room.” The dowry given, Bolak Sonday and Benobong are married to Daugbolawan and Lomelok. Upon his return to Liyasan, Sandayo falls ill. Bolak Sonday and Benobong are summoned to nurse Sandayo but Sandayo dies. The two women then search for the spirit of Sandayo. With the guidance of two birds, they discover that Sandayo’s spirit is a captive of the Amazons of Piksiipan. After defeating the Amazons in battle, Bolak Sonday frees Sandayo’s spirit and the hero comes back to life. One day, while preparing betel nut chew, Bolak Sonday accidentally cuts herself and bleeds to death. It is now Sandayo’s turn to search for Bolak’s spirit. With the aid of two birds, he discovers that Bolak Sonday’s spirit has been captured by the datu of Katonawan. Sandayo fights and defeats the datu, and Bolak Sonday is brought back to life. In Liyasan, Sandayo receives requests from other cousins to aid them in producing the dowry for their prospective brides. Using his powers, Sandayo obliges. After the marriage, a grand buklog is celebrated in Manelangan, where Sandayo and his relatives ascend to heaven.

In the Subanon long tales, the stock character of a widow’s son always possesses stupendous physical courage. The following is one of the numerous stories told about him.

One day, the widow’s son sets out to hunt for wild pigs. He sees one that gives him a difficult time before allowing itself to be speared. The owner of the pig, a deity who lives inside a huge white stone, invites him to his abode where the widow’s son sees opulence and a richness of colors. The master of the house inside the stone wears trousers and a shirt with seven colors. The widow’s son is invited to chew betel nut and sip rice beer from a huge jar, using reed straws. The matter of the pig is resolved, and the two become friends. On his return journey, he meets seven warriors who challenge him to a combat. Each of the seven men is dressed in a different color, and has eyes whose color matches that of his clothes. Forced into battle, the widow’s son slays all seven warriors, but the savage fighting gives him a thirst for more enemies to fight. He comes to the house of a great giant named Dumalagangan. He challenges the giant to a fight. The giant, enraged and amused by the challenge of a “fly,” engages him in a duel but is defeated after three days and three nights of combat. Battle-drunk, the widow’s son looks for more enemies, instead of going home where his mother waits anxiously for him. He meets another diwata, who passes his kerchief over him, rendering him unconscious. When the widow’s son wakes up, his rage is gone. The diwata tells him to go home, saying that he is destined to marry the orphan girl (another stock character in Subanon tales), that the seven warriors and the giant he has slain will come back to life, and that peace will reign in the land.

Trickster tales, with heroes named either Pilanduk or Pusung, are popular among the Subanon. In these tales, the trickster heroes demonstrate cleverness and play tricks on their superiors. In one tale, Pilanduk hides Donya Maria’s comb and pretends to find it for her. In the end, Pilanduk wins Donya Maria in marriage. Like Pilanduk, Pusung outsmarts the richer and more powerful king despite his ignorance and poverty. For instance, he becomes rich by fooling the king that the beach is a reservoir for food. Unknown to the king, Pusung had buried food at the beach.

Antonio Enriquez is a contemporary fictionist in English who has written about the Subanon. His two short stories, “The Turtle-Egg Hunter” and “Gatherer of the People,” narrate the beginnings and consequences of Spanish colonialism in the lives of the Subanon in the Zamboanga peninsula. Enriquez’s novel, Subanons, 1999, dramatizes the plight of the Subanon people caught between the government’s military operations against the New People’s Army at the height of martial law. Enriquez’s depiction of the urgent problems facing the Subanon is commendable, although his representation of the Subanon as helpless individuals who have no ability to fight and resist their oppression has been questioned.

Subanon Songs and Rituals

Video: Buklog, thanksgiving ritual system of the Subanen

For instrumental music, the Subanon have brass gongs, lutes, drums, bamboo zithers, and a variety of bamboo flutes. The brass gongs are called tungantong, 20 in or more in diameter and used for all occasions; gagong, a smaller 15-in gong used only during ritual events; and kolintang, a set of eight small brass gongs of graduated sizes.

|

| The Subanon performing the buklog, a communal ritual on top of a wooden platform (The Subanons of Sindangan Bay by Emerson B. Christie. Bureau of Printing, 1909) |

The musical instruments made from bamboo internodes are latong (drum), lunggal (five-stringed bamboo zither), takambubok (two-stringed bamboo zither), and five varieties of bamboo flutes: lantuyan, tumpong, tanggab, tinapo, and tulali. Each of these flutes has different lengths, mouthpieces, and numbers and locations of holes, thus producing a wide variety of sounds. The Subanon also have the kutapi, a lute played in courtship, and durugan, a hollowed-out log that is beaten like a drum.

Vocal music includes the chants for the epics and the different types of songs. Their chanter, originally, was the balian. Since a balian is either male or female, the songs of the Subanon can be chanted by both sexes, depending on the balian’s role in a particular social situation.

The general term for a song among the eastern Subanon is basamba. This is divided into four categories: lundi, tubadtubad, gumaman, and giloy. Lundi can be sung during a drinking session, a ritual for a child, or a ritual for a sick person. In wine-drinking ceremonies and during a ritual for a child, songs sung by a balian are invitations for spirits to participate in the ceremony. When this is sung during the ritual for the sick person, it brings particular spirits to come and cure illness.

Tubadtubad is a chant. It can also be communicated through media like gong, kutapi, takambubok, and lunggal. The story of the past generations is told through a song of history called gumaman. The length of the song depends on the length of the history. It has different melodies and is sung at a high pitch. Traditional values are transmitted through the gumaman.

Giloy is a sacred chant sung in rituals like the buklog, rituals associated with shifting cultivation, and funerals. The giloy is usually sung by two singers, one of them being the balian, during a gukas, which is the ritual ceremony performed as a memorial for the death of a chief. The chanting of the giloy is accompanied by the ritualistic offering of bottled drinks, canned milk, cocoa, margarine, sardines, broiled fish, chicken, and pork. The balian and her assistants bring out a jar of pangasi (rice wine) from the house and into the field, where the wine is poured onto the earth. Then the chanting begins inside the house. Here is an example of a giloy (Berdon-Georsua 2004):

Apo Asog dungawa

Da na remay gangoten

Eaoy! Ke bulak ni Katiolo,

Nandawin bembalanae

Eaoy! Apo Asog dungawan

Batang bayog mi bentay

Mi tenday siloy balay,

Apo dungawa ea,

Eeaay! Bata ni Ama Tama,

Etabang tabang amo

Gabang sogot laya mo

Bulak ni Katiolo

Su sembalan ta gusay!

(Apo Asog behold

There are no more roots

Eaoy! The flower of Katiolo

Yet, it still blooms

Eaoy! Apo Asog behold

Bayog trunk is lying

Settles under the house

Apo behold

Eeaay! Child of Father Tama

Help, everyone help

Help, you also obey

Flower of Katiolo

Let you bloom, we must!)

The Subanon have other types of songs such as the dionli (a love song) and buwa (lullaby). One buwa sung by the Subanon of the Sindangan Bay goes like this:

Buwa ibon

da dinig ina ta

da-a mngayod

ditong mnloyo li

tulog bais

buwa ibon.

(Rocking

your mother’s not here

do not cry

she is away

sleep well now

rocking.)

Another song, which is sung between friends, is “Mag Lumat Ita” (Let Us Play):

Salabok salabok

dini balay ta hin

glen da magtangao

mag lumpot ita glem

(One by one

here in my house

some of us will seek

we will play together.)

Subanon Ritual and Folk Dances

To be at peace with the diwata of the tribe, the Subanon perform ritual dances, sing songs, chant prayers, and play their drums and gongs. The balian, who is more often a woman, is the lead performer in almost all Subanon dance rituals. Her trance dance involves continuous chanting, frenzied shaking of palm leaves, or alternate brandishing of a bolo and flipping of red pieces of cloth. Upon reaching a feverish climax, the balian stops, snaps out of her trance, and proceeds to give instructions dictated by the diwata to the people.

|

| Subanon performing a traditional dance to the beat of a brass gong, 2014 (Estan Cabigas) |

Dance among the Subanon fulfills a multitude of ceremonial and ritual functions. Most important of the ritual dances is the buklog, which is performed on a platform at least 6 to 10 meters above the ground. The most expensive ritual of the Subanon, the buklog is held to commemorate a dead person so that his acceptance into the spirit world may be facilitated, to give thanks for a bountiful harvest, or to ask for such a harvest as well as other favors from the diwata.

The whole structure of the buklog platform sways and appears to be shaky, but it is supported at the corners by upright posts. In the middle of the platform, a paglaw (central pole) passes through, with its base resting on a durugan, a hollow log three meters long and as thick as a coconut trunk. It is laid horizontally on the ground, resting on a number of large, empty earthen jars sunk into the earth. These jars act as resonators when the paglaw strikes the durugan. The jars are kept from breaking by sticks and leaves that protect them from the durugan’s impact. The sound that the paglaw makes is a booming one and can be heard a few kilometers away.

In a typical performance of the buklog, gongs are beaten, songs are rendered—both traditional ones and those improvised for the occasion—and the people take turns sipping basi or rice wine from the reeds placed in the jars. As evening comes, and all through the night, they proceed to the buklog platform by ladder or notched log and join hands in a circle. They alternately close in and jump backward around the central pole, and as they press down hard on the platform in unison, they cause the lower end of the pole to strike the hollow log, which then makes a deep booming sound. It is only the balian who appears serious in her communication with the spirit world, while all the rest are more concerned with merrymaking, consisting of drinking, feasting, and dancing.

The balian does the dancing in other ceremonies such as for the recovery of a sick child. During the ritual offering of chicken, an egg, a chew of betel nut, a saucer of cooked rice, and cigarette made of tobacco wrapped with nipa leaf, the shaman burns incense, beats a china bowl with a stick, and beats a small gong called agun cina (Chinese gong), with the purpose of inviting the diwata mogolot (a class of deities who live in the sea) to share in the repast. Then she takes hold of salidingan in each hand and dances seven times around the altar. The salidingan are bunches of long strips of the salidingan or anahaw leaves.

In the puluntuh, a buklog held in memory of the dead, two altars are constructed, one underneath the dancing platform, another near it. These are for the male and female munluh. The munluh are also the manamat, maleficent beings of gigantic size who dwell in the deep forests. In the ceremonies, the munluh are invoked and given offerings so that they might keep the other manamat away from the festival. The balian dances three times around the altar and around the hollow log underneath the buklog platform, holding in one hand a knife and in the other a piece of wood and a leaf. The altar to the female munluh is served by two women balian who take turns beating a bowl, burning incense, and dancing. Unlike the male shaman, they carry no knife or piece of wood. The male balian’s dance differs from the female’s. In the former, the dancer hops over the ground with a quick step. In the latter, there is hardly any movement of the feet, but mostly hand movements and bodily gestures.

Many other kinds of dance, some of them mimetic, showcase the lively spirit of Subanon ritual. The soten is an all-male dance dramatizing the strength and stoic character of the Subanon male. It employs fancy movements, with the left hand clutching a wooden shield and the right hand shaking dried palm leaves. In a manner of supplication, he calls the attention of the diwata with the sound of the leaves, believed to be most beautiful and pleasing to the ears of those deities. The Subanon warrior, believing that he has caught the attention of the diwata who are now present, continues to dance by shaking his shield, manipulating it as though in mortal combat with unseen adversaries. The soten is danced to the accompaniment of music played on several blue and white Ming dynasty bowls, performed in syncopated rhythm by female musicians.

The diwata is a dance performed by Subanon women in Zamboanga del Norte before they set out to work in the swidden. In this dance, they supplicate the diwata for a bountiful harvest. The farmers carry baskets laden with grains. They dart in and out of two bamboo-planting sticks laid on the ground and struck together in rhythmic cadence by the male dancers. The clapping sequence is similar to that of the tinikling or bamboo dance.

The lapal is a dance of the balian as a form of communication with the diwata, while the soten is a dance performed by Subanon men before going off to battle.

The balae is a dance performed by young Subanon women looking for husbands. They whisk dried palm leaves (see logo of this article), whose sound is supposed to please the deities into granting their wishes.

The pangalitawao is a courtship dance of the Subanon of Zamboanga del Sur, usually performed during harvest time but also in other social occasions. Traditional costumes are worn, with the women holding shredded banana leaves in each hand, while the men hold a kalasay in their right hand. The change in steps is syncopated. The women shake their banana leaves downward, while the men strike the kalasay against the palm of their hand and against the hip. A drum or a gong is used to accompany the dancing.

The sinalimba is an extraordinary dance that makes use of a swing that can accommodate 3-4 persons at a time. The term is also used to mean the swing itself, a representation of a mythic vessel used for journeying. Several male dancers move in rhythm to the music of a gong and drum ensemble playing beside the swinging sinalimba. At a specific movement of the dance, one of them leaps onto the platform, steadies himself, and moves with the momentum of the swing. Once he finds his balance, he forces the sinalimba to swing even higher. This requires considerable skill since he has to remain gracefully upright, moving in harmony with the sinalimba as though he were a part of it. The other two or three performers follow him onto the sinalimba one after the other, making sure they do not disrupt the pendular rhythm of the swing. A miscue could disrupt the motion, and even throw them off the platform. Even as they end the dance, they must maintain their agility in alighting from the sinalimba without counteracting or disrupting the direction of the swing.

Subanon People as Featured in Media

Several radio programs in Zamboanga peninsula occasionally feature the Subanon. Christian station 1116 DXAS "Your Community Radio" in Western Mindanao, for example, uses the Subanon language in some of its shows. DXMG 88.7 Radyo Bisdak Ipil Sibugay airs The Voice of the Mountains Subanen Special, a show about Subanon life, culture, and history that started in January 2018. Hosted and produced by Subanon pastor Allan Mangangot, who is active in the Christian and Missionary Alliance Churches of the Philippines, the show had featured topics that range from the Subanon customary laws to problems they usually face. The show's Facebook page Subanen Ako 2020 enables it to reach a wider audience, including Subanon within the country and overseas.

Subanon culture, particularly the buklog ritual, are well documented by various institutions. The Living Asia Channel and ABS-CBN’s Travel Time hosted by Susan Calo-Medina depict the Subanon and their lifeworld in commercial and touristy lenses. South Korea-based and UNESCO-funded International Information and Networking Centre for Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Asia-Pacific Region, in partnership with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, produced Buklog: The Ritual System of the Subanen of Zamboanga Peninsula, 2019. This documentary details how buklog, inscribed in the UNESCO list of Intangible Cultural Heritage, should be protected amid the ever-changing times.

In 2015, Mindanawon Perry Dizon produced his debut film Of Cats, Dogs, Farm Animals and Sashimi. It depicts the life of a young Subanon named Dondon who engages in various work in small farm, fishing community, and abaca plantation in Zamboanga Sibugay. The film pieces together Dondon’s fragmented hopes and his transformation from a young Subanon who finds solace in playing with dogs and cats to a grown-up striving to find a living within the picturesque landscape of Zamboanga Bay. Beyond the adventures and new discoveries, the film portrays the uncertainties and violence in life outside the small farm owned by a rich family in Tangalan, Alicia, Zamboanga Sibugay. The film was exhibited at the 2015 QCinema International Film Festival and 2017 Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival in Japan. It received a Special Jury Mention at the 2016 Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival and was nominated for Best Documentary at the 2016 Gawad Urian.

Sources:

- Aleo, Edgar et al. 2002. A Voice from Many Rivers: Su Gesalan Nu nga Subaanen Di Melaun Tinubigan. Translated and annotated by Felicia Brichoux. Manila: Linguistic Society of the Philippines.

- Bankoff, Greg. 1991. “Deportation and the Prison Colony of San Ramon, 1870-1898.” Philippine Studies 39, 4: 443–457.

- Berdon-Georsua, Racquel. 2004. “Where Heaven and Earth Meet: The Buklog of the Subanen in Zamboanga Peninsula, Western Mindanao, the Philippines.” PhD dissertation, The University of Melbourne.

- Casal, Gabriel S. 1986. Kayamanan: Mai: Panoramas of Philippine Primeval. Manila: Central Bank of the Philippines, Ayala Museum.

- Christie, Emerson B. 1909. The Subanons of Sindangan Bay. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

- ———. 1912. “Report on the Drinking Customs of The Subanuns.” Philippine Journal of Science 7A (2): 114-117.

- Elago, Marilou C., Rhea Felise A. Dando, Jhoan Rhea L. Pizon, Rainier M. Galang, and Isidro C. Sia. 2013. “Phase II Documentation of Philippine Traditional Knowledge and Practices on Health and Development of Traditional Knowledge Digital Library on Health for Selected Ethnolinguistic Groups: The Subanon people of Malayal, Sibuco, Zamboanga del Norte.” Philippine Council for Health Research and Development and the Institute of Herbal Medicine.

- Enriquez, Antonio. 1999. Subanons. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

- ———. 2003. The Voice from Sumisip and Four Other Stories. Quezon City: Giraffe Books.

- Finley, J.P., and William Churchill. 1913. “Ethnographical and Geographical Sketch of Land and People.” In The Subanu: Studies of a Sub-Visayan Mountain Folk of Mindanao, part 1. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington.

- Frake, Charles O. 1957. “Sindangan Social Groups.” Philippine Sociological Review 5 (2): 2-11.

- ———. 1960. “The Eastern Subanun of Mindanao.” In Social Structure in Southeast Asia, edited by George P. Murdock. New York: Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research Inc.

- ———. 1962. “Cultural Ecology and Ethnography.” American Anthropologist 64: 53-59.

- ———. 1964. A Structural Description of Subanun Religious Behavior.In Explorations in Cultural Anthropology: Essays in Honor of George Peter Murdock, edited by Ward Goodenough. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Gabriel, Ma. Obdulia. 1964. “Educational Implications of the Religious Beliefs and Customs of the Subanuns of Labason, Zamboanga del Norte.” MA thesis, Xavier University.

- Jocano, F. Landa. 1975. Philippine Prehistory: An Anthropological Overview of the Beginnings of Filipino Society and Culture. Quezon City: Philippine Center for Advanced Studies.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2014. Ethnologue: Languages of The World, 17th ed. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Accessed 10 June. http://www.ethnologue.com.

- Malagar, Esterlinda M, trans. “The Guman of Dumalinao.”1980. Kinaadman 2: 253-380.

- Mojares, F.S. 1961. “The Subanons of Zamboanga.” Filipino Teacher 15 (8): 538-541.

- National Statistics Office. 2010. Census of Population and Housing-Region IX.

- Ochotorena, Gaudiosa, trans. 1980. “Pematay nog Getaw: Subanun Guman (The Death of Man).” Zamboanga City: Western Mindanao State University Research Center.

- ———. 1981. “Ag Tobig nog Keboklagan: A Folk Epic.” Kinaadman 3: 343-543.

- Regional Map of the Philippines – IXA. 1988. Manila: Edmundo R. Abigan Jr.

- Resma, Virgilio N., trans. 1982. “Keg Sumba neg Sandayo.” Kinaadman 4: 259-426.

- Sembrano, Edgar Allan M. 2021. “UNESCO, NCCA team up for docus on PH Heritage.” Inquirer.net. Retrieved 2 June 2021, https://lifestyle.inquirer.net/380464/unesco-ncca-team-up-for-docus-on-ph-heritage/.

- This article is from the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Digital Edition. Title: Subanon. Author/s: Edgardo B. Maranan (1994) / Updated by Vel J. Sumingit, with additional notes from Jay Jomar F. Quintos and Rosario Cruz-Lucero (2018) / Updated by Jay Jomar F. Quintos (2021). Publication Date: November 18, 2020. Access Date: September 16, 2022. URL: https://epa.culturalcenter.gov.ph/1/2/2372/

![Subanon (Subanen) Tribe of Zamboanga Peninsula: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Mindanao Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group] Subanon (Subanen) Tribe of Zamboanga Peninsula: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Mindanao Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhMwR06G47KGsPlmUY9Ttt87soLBq_iX-1oaiz2zpNKD6zaye8WPasHCim7kz0BtZdKMHYJqkgXFrnDQo2HUA7KY-WCVe5Xjk4IR8XQhEe3TSF6aZligxdaOcP7NxrI18OpUBGd1IgzJknqIXa3r1q9p2whqRaU8GGJbclxR33qVj6LU_JdeA/s16000-rw/Island%20Escape.png)

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?