Tiruray (Teduray) Tribe of Mindanao: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group]

The Tiruray, also called Teduray, are a traditional hill people of southwestern Mindanao. They live in the upper portion of a river-drained area in the northwestern part of South Cotabato, where the mountainous terrain of the Cotabato Cordillera faces the Celebes Sea. The word “Tiruray” comes from tiru, signifying “place of origin, birth, or residence,” and ray from “daya,” meaning “upper part of a stream or river.”

The Tiruray call themselves etew teduray or Tiruray people, but also classify themselves according to their geographic location: etew rotor, mountain people; etew dogot, coastal people; etew teran, Tran people; etew awang, Awang people; and etew ufi, Upi people. The Tiruray may also be classified into the acculturated and the traditional. The first refers to those who live in the northernmost areas of the mountains and who have had close contact with Christian and Muslim lowland peasants, as well as with Americans since the beginning of the century. The second refers to Tiruray who have survived deep in the tropical forest region of the Cotabato Cordillera and have retained a traditional mode of production and value system.

The Tiruray comprise the largest indigenous group in the entire Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM). As of 2002, they number about 50,000, distributed in several areas of the municipality of Upi and the province of Cotabato: the coastal region, the northern mountain region, the Upi Valley, the Tran Grande River, and Maganoy (now Shariff Aguak) River regions. In Upi alone, they number about 22,502, which is 44% of its total population of 51,141. The entire mountainous stretch, in the seaward portion of northern Maguindanao, is also home to two other cultural groups who are linguistically distinct from the Tiruray and from each other: the nearby Cotabato Manobo and the Tboli. The Tiruray are Malay in physical appearance. Their language is structurally related to those of the Malayo-Polynesian family, but when spoken, it is unintelligible even to their immediate neighbors.

History of the Tiruray Tribe

The Tiruray share a common mythic ancestry with the Dulangan Manobo and the Maguindanaon. These three groups believe they are descendants of the brothers Mamalu and Tabunaway. Mamalu, the older brother, did not convert to Islam, which Shariff Kabungsuan had brought to Mindanao, whereas Tabunaway did. This caused their separation, each taking his followers with him. Mamalu, whose descendants became the Tiruray and the Dulangan Manobo, lived in the mountains, while Tabunaway, ancestor of the Maguindanaon, lived and started trading in the lowlands and the areas surrounding the Rio Grande.

|

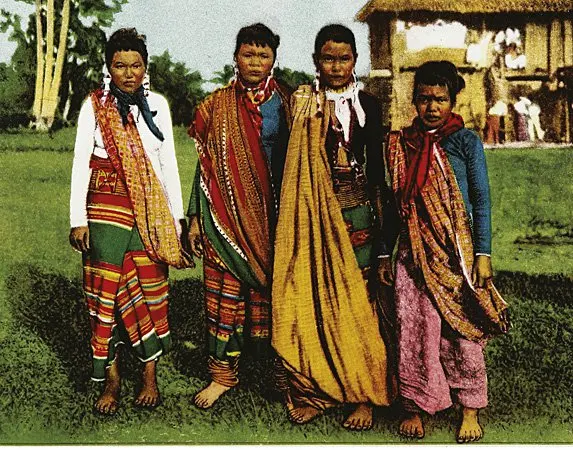

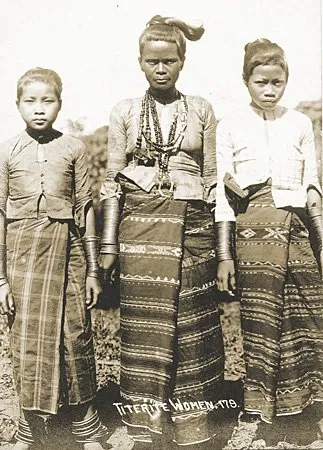

| Tiruray women (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The Tiruray have occupied the same area for several centuries, but they have undergone varying degrees of assimilation and acculturation. It is reasonable to assume that before the Spanish appeared in Mindanao, there was extensive contact between the Tiruray and the Maguindanaon Muslims, particularly since the 15th century. During that time, the people of the Cotabato River basin had been won over to Islam, which had established a sultanate over all of Maguindanao. Attempts by the Maguindanaon to subdue the mountain tribes of Cotabato did not succeed, but trade relations eventually flourished between the two groups. The Tiruray came down to the coast bringing forest and agricultural products for trade, including tobacco, beeswax, rattan, sap of a tree called tefedus, almaciga, and crops.

Spanish influence in the area came rather late. It was only sometime in the 19th century, toward the end of Spain’s colonial rule in the Philippines, that the central government in Manila and the Roman Catholic Church were able to establish a stronghold in Cotabato. A Spanish military garrison was put up in Cotabato City, while a Jesuit school and mission were built near Awang, close to the mountain region, where the Spaniards converted a number of Tiruray to Catholicism.

The outbreak of war between the American occupation forces and the Muslim people of Mindanao in the early part of the 1900s signaled the beginning of another phase of colonization. The Americans, through the efforts of a Philippine Constabulary officer named Irving Edwards, who married a Tiruray, built a public school in Awang in 1916 and an agricultural school in Upi in 1919. The building of roads that ran into Tiruray territory opened up the region to numerous lowland Christian settlers, most of them Ilocano and Visayan, and Upi Valley became the site of many homesteads. Further causing the Tiruray’s loss of their land was the Americans’ introduction of the titling of lands as homesteads.

A significant number of Tiruray were persuaded to give up their traditional slash-and-burn methods of cultivation, and they shifted to farming with plow and carabao. This was the beginning of the divide in Tiruray culture: many Tiruray refused to be acculturated and retreated deeper into their ancestral mountain habitat, while others resettled in the Upi Valley and became peasants. Many of the resettled and “modernized” Tiruray have been converted to Christianity, as a result of years of evangelization work by American missionaries, Filipino migrants, or converted Tiruray themselves.

The municipality of Upi was opened up to the world during the American colonial period with the construction of the road connecting it to Cotabato City. However, this 30-kilometer road was rough: travel between Upi and Cotabato would take about half a day and longer during the rainy season. It was not until 2011 that this road became completely concrete, forming a segment of the 105-kilometer road connecting the municipalities of Awang, Upi Lebak, and Kalamansig. Travel time has been cut to a mere 40 minutes.

On the other hand, the Tiruray’s political and economic situation has remained basically unchanged since the American period. Power is mainly in the hands of the Maguindanaon, who make up the majority population—more than half a million—in the rural and urbanized parts of the province. Local and provincial leaders, under the local government setup centralized in Manila, are mainly Maguindanaon.

Historically, the relationship between Christian settlers in Mindanao and the Tiruray was relatively amiable. The Tiruray were not as involved in negotiations for acquisition of land as the powerful Maguindanaon who have ties to the national government (Abinales 2012, 86). However, in the 1960s, as the Mindanao settlement program was coming to an end, President Ferdinand Marcos began to form patronage ties in various levels and forms, in a deliberate attempt to weaken the power of his Maguindanaon opponents. Hence, conflict between the Tiruray and other groups started brewing.

In March 1970, an armed group of Tiruray led by Feliciano Luces, a Christian Ilonggo, figured in a violent encounter against local Muslim outlaws. Luces, a settler who was seeking to avenge the killing of his family by some Maguindanaon individuals, later gained notoriety as Kumander Toothpick of the militia Ilaga, literally “rat” (Abinales 2012, 87). Initial reports about Luces portrayed him as a Robin Hood-like figure, a defender of the poor from the exploitation of the elites. Subsequent reports, however, implied that his actions might be politically motivated and that he was associated with a mayoralty candidate in Upi perceived to be pro-Marcos (Kaufman 2012, 944).

In times of conflict, Tiruray and Maguindanaon leaders have been known to appeal to their shared mythic history, that is, the story of their ancestors coming from the same family, which had split into two clans when Mamalu and Tabunaway separated. As of 2013, in light of efforts toward the creation of a new Bangsamoro region, leaders from both groups have been calling for a reaffirmation of the Mamalu-Tabunaway mythic kinship for the sake of peace and solidarity.

Although they have been traditionally characterized as politically “weak” (International 2011, 11), the Tiruray have in recent years started to make crucial leaps in local government. The first mayor of the town of Upi, Maguindanao, where the majority of the Tiruray reside, was Ignacio Tenorio Labina, a Tiruray leader who held the post from 1956 to 1960 (Municipality of Upi 2013). All the subsequently elected mayors, however, were Maguindanaon, until 2001 when Ramon A. Piang Sr. became Upi’s first Tiruray mayor after four decades.

Piang, a former seminarian and school principal, entered politics with the express intention of representing the Tiruray people and their collective need. He ran for and won as vice mayor of Upi in 1992. When his term as vice mayor ended in 2001, he ran for mayor. Despite his rivals’ attempts to make him back down, Piang persisted, saying it was his elders who were urging him to run for mayor and hence, only they could persuade him to withdraw. He won the heated election with the support of the residents of Upi, who guarded their votes with a vigilance that they called “people power.”

Livelihood of the Tiruray People

For a long time, the Tiruray practiced a subsistence system mainly based on traditional swidden cultivation. Supplemental food supplies were procured through hunting, fishing, and gathering. Other necessities of life, such as iron tools for slash-and-burn agriculture, household implements, and personal items, were obtained through trade with the Maguindanaon. Weaving, blacksmithing, and pottery are industries unknown to the Tiruray. They used to wear hand-beaten bark cloth. Cotton material, particularly the sarong dress, only came in through trade activities. These articles were obtained by exchanging them for their rattan, almaciga, beeswax, and tobacco.

Among the more populous settlements of Tiruray, internal trade goes on during market days. The traders are mainly menfolk because the Tiruray females are extremely shy and not much given to business transactions. It is they, however, who carry the barter products to the market for their husbands. Tobacco is the main crop cultivated for the barter market, but some rice and corn are also grown for commerce, to meet basic needs in the house, such as knives, chicken, and piglets. The Tiruray who have turned to plow farming in the lowlands have been integrated into the cash, credit, and market economy, and follow agricultural techniques and crop selection entailed by a peasant type of economic production.

Following an indigenous system of astronomy, the Tiruray reckon the beginning of their swidden cycle by referring to the appearance of certain constellations in the night sky. By December or early January, swidden sites are ritually marked. This is followed by the laborious clearing of the thick forest growth and the cutting down of the big trees. All the menfolk of a settlement work on each household’s swidden site until all the swiddens are cleared, ready for burning by March or April. Corn and several varieties of rice are planted in the clearing, with men and women working together. The women take charge of harvesting and storing the first corn in May or June and the first rice in August or September. The next phase is the planting of tobacco or a second crop of corn, as well as more tubers, fruits, vegetables, spices, and cotton. Tiruray upland farming is as scientific and environmentally sound as all other indigenous swidden methods. After all the harvest has been done, “the field will not be further prepared or planted until it has lain fallow for many years, so that the vital jungle vegetation may be reestablished” (Schlegel 1970, 14).

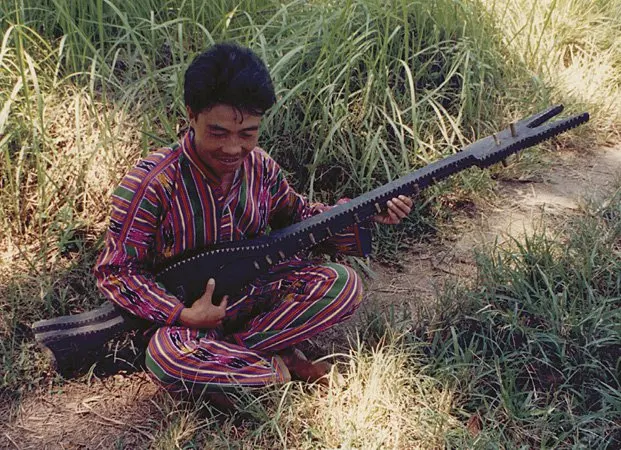

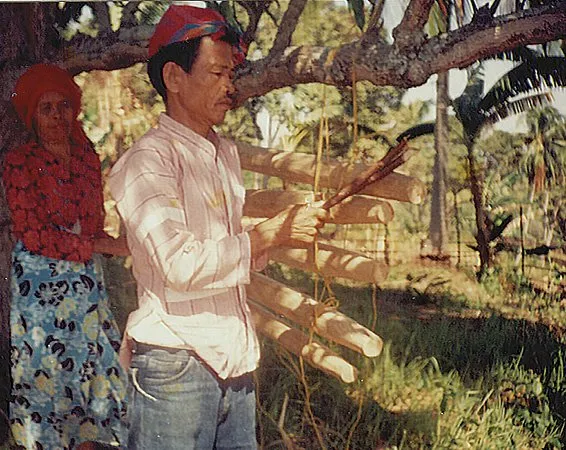

Since ancient times, the Tiruray have been known as skillful hunters and trappers. A total of 28 hunting methods and the same number of fishing methods have been recorded by Schlegel (1970). The Tiruray prepare their traps for deer and pig when their swidden crops have started growing on the hillside slopes. The fresh shoots creeping out from a burnt clearing usually attract the animals, which come out of the forest to forage for food. When the swidden fields have been planted to crops, there is not much work left to be done for the menfolk, except hunting, fishing, and gathering food in the jungle. Aside from their skill at setting traps and snares, Tiruray hunters are experts in using the blowgun, bow and arrow, spear, and the homemade shotgun, this last weapon acquired after World War II.

In the last half-century, the classification of Tiruray society into traditional and acculturated has been most pronounced in the differentiation of their subsistence systems. The first system is traditional swidden agriculture, such as that in the settlement of Figel in 1979. The other is a peasant economy, which describes the settlement of Kaba-Kaba. Swidden agriculture is adapted to the tropical rainforest, consisting of slash-and-burn and shifting cultivation. It is augmented by hunting, fishing, and food-gathering activities, and is only marginally dependent on trade with the coastal economy. The peasant economy consists of plow farming in areas which have virtually lost the old forest cover, with almost no exploitation of or dependence on forest resources, and it has an extensive involvement with the market economy of a rural lowland society.

The Tiruray Community

The political organization of Tiruray society is not hierarchical. Each inged (neighborhood) of subsistence groups may have a leader who sees to the clearing of the swidden, the planting and harvesting of crops, and the equal sharing of the rice or any other food produced from the land. The leader or head also determines, in consultation with the beliyan (shaman), where to move next to clear another swidden settlement.

|

| Municipal Hall Building, Upi, Cotabato, 2013 (Municipal Government of Upi, Cotabato) |

Tiruray society is governed and kept together by their adat (custom law) and by an indigenous legal and justice system designed to uphold the adat. Legal and moral authority is exercised by an acknowledged expert in custom law called kefeduwan. The expert presides over the tiyawan (formal adjudicatory discussion board), before which cases involving members of the community are brought for deliberation and settlement. The kefeduwan’s position is not based on wealth, as there is hardly any economic stratification among the traditional Tiruray. It is not a separate position or profession because he continues to carry on the usual economic activities of other menfolk in the community. The most learned in Tiruray customs and law, possessing a skill for reasoning, a remarkable memory, and an aptitude for calmness in debate, and “who learns to speak in the highly metaphorical rhetoric of a tiyawan,” is apt to be acknowledged as a kefeduwan. In one inged, there may be more than one kefeduwan and several more minor kefeduwan. The main responsibility of a kefeduwan in Tiruray society is to see to it that the respective rights and the feelings of all the people involved in a case up for settlement are respected and satisfied.

The central goal in the Tiruray system of justice, according to Schlegel (1970), is for everyone to have a “good fedew,” which means one’s state of mind or rational feelings, one’s condition of desiring or intending.” The legal and moral authority of the kefeduwan exists for this social goal. Thus, the administration of justice is geared toward the satisfaction not only of one party but of both sides. This institution has made possible a significant development in the Tiruray justice system. In the past, retaliation was deemed the acceptable means of seeking justice, but with the ascendancy of the tiyawan, retribution has been reduced to the payment of fines or damages.

Internally, this traditional system of justice is still followed, especially in the interior settlements where the old lifeways and practices are still followed. But like most other ethnolinguistic groups in the country, the Tiruray are subject not only to the formal structures of local government under national law but also to the pressure of political change. Political ascendancy, as noted earlier, resides with the predominantly Muslim population in Maguindanao. In recent years also, the Tiruray have been caught in the crossfire between the government and insurgent forces operating in Mindanao.

In 1989, through Republic Act 6734, the ARMM was created. Maguindanao was one of the four provinces that opted for inclusion in the newly formed region. Because the majority of the Tiruray reside in Maguindanao, they came under the ARMM regional government, making them the largest indigenous group in the entire ARMM.

However, there is a disparity between the Tiruray’s vision of a better future for themselves and that of the Moro groups. In peace negotiations with the national government, the Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) and later, the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), demand Bangsamoro autonomy and self-determination. The Tiruray, on the other hand, are asserting their right to their ancestral domain, that is, their legal ownership of the land they have lived in since their ancestors’ time. Such differences between the concerns of the Tiruray and the Bangsamoro complicate the peace negotiations, especially when there are overlapping claims over vast areas of native lands (International 2011). Causing further tension in the region is the fact that the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997, which provides for the Tiruray’s claims to their ancestral domain, does not apply to the ARMM (International 2011).

Negotiations between the national government and the MILF led to a Memorandum of Agreement on Ancestral Domain (MOA-AD) in 2008. The Supreme Court, however, blocked it, declaring it unconstitutional. It ruled that the MOA-AD erred in defining Bangsamoro to include not only the Moros but also all indigenous peoples in Mindanao. The Supreme Court also sided with petitioners who said they had not been consulted on the matter (Supreme Court 2008). The failure of this deal on ancestral domain led to further division and mistrust in the ARMM (International 2011).

During the administration of President Benigno Aquino III, the national government and the MILF renewed peace negotiations, leading to a 2012 framework agreement on the creation of the Bangsamoro, a new political entity that would replace the ARMM. A comprehensive agreement was signed on 27 March 2014, with annexes on revenue and wealth sharing, power sharing and normalization, and an addendum on Bangsamoro waters.

The Bangsamoro Transition Commission has been constituted to draft the Bangsamoro Basic Law, which will define the Bangsamoro as a political and governing entity. This body includes two Tiruray members: Froilyn Mendoza and Timuay Melanio Ulama. Mendoza, an advocate of the rights of lumad women, is from South Upi, Maguindanao, and is one of the founders of the Teduray Lambangian Women’s Organization. Ulama is a consultant of the MILF on indigenous peoples and is the head of the Organization of the Teduray and Lambangian Conference.

While rido (justice by retaliation) has been noted between Tiruray and Maguindanaon, the municipality of Upi has been recognized nationally for its novel way of keeping peace and order through a local initiative that highlights the traditional Tiruray justice system, which centers on “good fedew.” In 2001, Mayor Ramon Piang Sr. created a council that would amicably settle conflicts and consequently declog the courts. The tri-people composition of the Maguindanaon population is evenly represented in this council: two kefeduwan (leaders of the Tiruray council of elders), two imam (Muslim religious leaders), and two Christians. The council’s first case, in February 2002, was a road accident involving Muslim victims and a truck owned by a Christian. Although the situation could have escalated into violence, the council acted swiftly and efficiently to settle the matter.

Video: The Tiruray Tribe of Sitio Kyamko

Tiruray Tribe Culture, Customs and Traditions

Tiruray communities are organized in settlements of 5 to 20 families called dengonon. These are actually small, dispersed hamlets, spread out over a large area. The basic residential unit is a nuclear family composed of the parents, unmarried children, and married children who have not yet put up their own dwellings. Sometimes unmarried and dependent elders form part of the household, which also includes the many wives of the household head. The Tiruray word for family is kureng, which means “pot,” for a family is deemed to be a group of persons living together and eating from the same pot.

|

| Tiruray family, 1970 (Filipinas Heritage Library) |

The largest social unit is the inged, which usually comprises several settlements. The households belonging to the inged render mutual assistance among themselves in all swidden-related activities, as well as in all the community rituals. Ordinarily, almost all members of the inged are linked to one another either by blood or through marriage ties.

In earlier times, members of a neighborhood shared a single large house. This seems to have been the rule in a period of political instability on account of tribal wars.

Starting from the American occupation, with the territory more or less pacified through military control, Tiruray families started living in individual houses. The term setifon, which means “of one house,” is still used to refer to all members of one neighborhood. The one large house in the inged is where the kefeduwan normally stays. A strict code of responsibility for feeding and provisioning the household is followed by the head of the kureng, whether he is monogynous or polygynous. All property, money, and crops are jointly owned by the household, with the wife seeing to it that economic tasks, responsibilities, and rights are properly adhered to within the kureng. A polygamous marriage can be allowed only if the first wife gives her consent. Furthermore, the senior wife becomes the “first among equals,” acting as chief spokesperson for all the other wives with regard to their rights and duties within the household.

|

| Tiruray women, 1913 (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

In Tiruray society, marriage takes place when the man’s relatives have succeeded in accumulating the tamuk (bride-price). Consisting of animals, valuables, and other articles, the tamuk is delivered to the parents of the bride. During marriage, relatives of the groom are called upon to contribute their share of items making up the bride-price. The kefeduwan and their family are enjoined to assist in performing the marriage rites. The role of the bride’s relatives is to help in the determination and distribution of the bride-price. When a person dies, relatives are summoned to share among themselves the costs of the funeral rites.

The kinship terminology follows the generational structure and is reckoned bilaterally from the father’s and mother’s lineage. The kinship terms used are eboh, father; ideng, mother; ofo, older sibling; tuwarey, younger sibling; and eya, child. After marriage, brothers are likely to combine or join their families together into one household. The same practice holds true for sisters who get married. In the old days, child marriages were common.

Inside the kureng, the closest relationship possible is that between husband and wife. Their children will eventually grow up, have their own spouses, and set up their own kureng. So long as their marriage lasts, they will live permanently together in the same “pot.” The closeness of man and woman in marriage is partly explained by the division of labor between men’s work and women’s work in the Tiruray swidden. It becomes very necessary that “every farmer has an active wife and that each adult and active woman be wedded to a working husband” (Schlegel 1970, 19). This is why selamfa, “elopement with a married person,” is considered a grave transgression against Tiruray society: the very fabric holding it together is threatened.

It is acceptable to have a duwoy, a “co-wife,” which could be more than one. There are several reasons for a polygynous relationship. The most common is the death of a relative who leaves behind a widow. The man is allowed to accept the widow into his kureng. Or, a man may desire to add on to his social prestige and increase his sexual satisfaction by taking in an additional wife, particularly a young woman. Another acceptable reason is the need to sire children if his first wife cannot bear him any. The one condition is that the tafay bawag, the senior or first wife, must give her consent. While she can always prevent her bawag (husband) from marrying another wife or any number of wives, in practice it is the woman who often suggests that her man take in a duwoy because of the perceived advantage in the arrangement: she will have another person to share the burden of so much work in the house and in the swidden. The tafay bawag exercises clear authority over the other wives. She assigns to them a share of the work in her husband’s fields. Everything that they produce is owned communally. The first wife sees to it that all of the duwoys’ pots receive an equitable share of the food.

Socialization for the children starts at an early age. They are suckled by their mother up to the age of two or three, or for as long as no new baby has arrived. But once they are able to walk, they are allowed to play around the village without any supervision from the elders. When they reach the age of six, they become little helpers in the swidden fields. Boys are assigned the tasks of gathering firewood, tending the farm animals, hunting wild birds with their little blowguns, guarding the fields from marauding monkeys, and the like. The girls, on the other hand, help in pounding the rice, weaving rattan baskets, fetching water, and washing clothes. In working, the Tiruray children learn all there is to know about surviving in their society, so that “by the time they are adolescents, they do the same work as their parents, and... have absorbed the skills they need to function as Tiruray adults” (Schlegel 1970, 21).

Many adult Tiruray have had either no formal education or only a low level of education. This has made them prone to social and economic exploitation and prevents them from having the economic benefits of education that their fellow Filipinos generally enjoy. The timuay (community leader of the Subanon), however, have been actively helping Tiruray children learn better in school. In 2013, newly elected ARMM deputy governor for Indigenous Peoples Timuay Hilario Tanzo sponsored a workshop to integrate Tiruray norms, traditions, and customs into the curriculum of their youth.

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Tiruray People

According to the Tiruray, the world was created by the female deity Minaden, who had a brother named Tulus, also called Meketefu and Sualla. Tulus is the chief of all good spirits who bestow gifts and favors upon human beings. He goes around with a retinue of messengers called telaki. Tulus is said to have rectified some errors in the first creation of the world and of human beings. In the complex cosmogony of the Tiruray, tiyawan (relationship) can exist between human beings and the spirits of the unseen world. The universe, according to the Tiruray, is the abode of various types of etew or people. There are visible ones, the keilawan (human beings), and invisible ones, the meginalew (spirits). The latter may be seen but only by those in this world possessing special powers or charisma. It is believed that the spirits live in tribes and perform tasks in the other world, much as they did on earth.

|

| Tiruray farmers performing a harvest ritual, 1993 (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

While good spirits abound in the world, there are also bad spirits who are called busaw. They live mostly in caves and feed on the remoger (soul) of any hapless human being who falls into their trap. At all times, the Tiruray, young and old, are aware that the busaw must be avoided, and this can be successfully done if one possesses charms and amulets. With the good spirits, it is always necessary and beneficial to maintain lines of communication. But the ordinary human being cannot do this, and so the Tiruray must rely on the beliyan (religious leader). The beliyan has the power to see and communicate with the spirits. If a person falls ill and the spirits need to be supplicated, the beliyan conducts a spiritual tiyawan with them. Human illness, insofar as the Tiruray is concerned, is the consequence of an “altercation,” a misunderstanding between people and the unseen spirits, and these formal negotiations are needed to restore the person’s health and harmonious relationship with the spirits. In effect, therefore, the beliyan as a mediator between spirits and human beings is a specially gifted and powerful kefeduwan.

In an account written in the late 19th century by Sigayan, the first Christianized Tiruray, christened Jose Tenorio, the beliyan was described as a person who could talk directly to Tulus and even share a meal with him. The beliyan would gather people in a tenines, a small house where the shaman stored the ritual rice, and tell them about his or her communications with Tulus. The beliyan would dance with a wooden kris in the right hand, small jingling bells hanging from the wrists, and a decorated wooden shield held in the other hand. The shaman made the men and women dance, for that was the only way the people could worship Tulus. The beliyan also prepared the ritual offerings to Tulus, and played the togo, a small drum, for the supreme being. The same account avers that the Tiruray believed in heaven, a place where they go after death. There was also a hell-like place called naraka, but this was for the Maguindanaon, “because their god is a different one” (Tenorio 1970, 372).

The ancient belief in Tulus and other cosmological beings has remained, and so has the belief in the efficacy of charms and omens. These are particularly relevant in the hunting activities of the Tiruray, whose basic charm or talisman is the ungit. This is fashioned from several kinds of “mystically powerful leaves and grasses, wrapped in cloth and bound with vine lashing” (Schlegel 1979, 235). This is handed down from father to son, and down the line. The kinds of plants that make up the charm are strictly kept between father and son, as revealing these to just anybody will cause the charm to lose its potency. The hunter carries the ungit on his body and rubs it all over his dog and horse. The ungit is believed efficacious not only in snaring or catching game but also in attracting women sexually. If so used, however, “it loses its power as a hunting charm” (Schlegel 1979, 235).

Omens rule the life of hunters, as they presage misfortune. A hunter will not proceed on a hunt if any of these occurs: he hears a person sneeze as he is about to set out; he hears the call of a small house lizard; or he has a bad dream in which he gets wounded, falls, or dies. He will give up the hunt if the animal he intends to catch is seen while he is setting up the trap.

Rituals to establish good relations with the spirits accompany each significant stage of the Tiruray agricultural cycle. Four times within the year, all the households belonging to the inged participate in a community ritual feast known as kanduli. Feasting on food, particularly glutinous rice and hardboiled eggs, and ritual offerings to the spirits are the two characteristics of these annual celebrations. The preparations for the feast are generally done in the major settlement within the inged, which is also the focal point of all activities. In the preparation of the food, a significant ritual act is already performed: the exchange of portions of the glutinous rice among all the families. When it is time to consume the ritual food, a family would then partake of the rice that has come from every other family in the whole neighborhood. The bonding of the community and of all individual members through the food exchange is implicit in the practice. The significance is further underscored by the fact that “in the course of the cultivation cycle, every family of the neighborhood had contributed its labor to each field on which the rice was grown, and it is the effect of these communal meals to give ritual expression to this interdependence” (Schlegel 1970, 64-65).

There are four kanduli rituals of the agricultural cycle: maras, “marking festival,” which is held on the night of the last full moon before the marking of swidden sites for the coming cycle; retus kama’s, “festival of the first fruits of the corn,” which is held on the night following the first corn harvest from a neighborhood swidden; retus farey, “festival of the first fruits of the rice,” which is celebrated on the night following the first harvest of rice from a swidden; and matun tuda, “harvest festival,” which is held on the night of the first full moon when the rice harvest from all of the settlement’s swiddens has been collected.

The inged families prepare small bamboo tubes filled with glutinous rice, and these they offer to the spirits during the ritual marking of the first swidden site. Men and women of the neighborhood congregate at a clearing, and they proceed in single file as gongs are being played to where the first swidden for the year will be marked for burning. Arriving at the site, they set up a small platform where they lay down the tubes of glutinous rice. Everyone listens attentively to the omen-call of the lemugen bird, which is believed to have the power to convey messages between human beings and the spirits. The first ritual marking is meant as a song of respect for the spirits of the forest, seeking permission to begin cutting down the trees. The owner of the field interprets the omen-call, and there are good signs and bad signs, depending on the direction of the call. There are four good directions: selat (front), fereneken (45 degrees left), lekas takes (45 degrees right), and rotor (directly overhead). Any other direction is considered bad. The ritual laying of the food and the wait for the omen-call is repeated around the four corners of the swidden until a good omen is heard.

Because Spanish colonialism had very little or no impact at all on the Tiruray, there were very few converts to Catholicism. The Americans were more successful in their mission work. An American officer of the Philippine Constabulary, Irving Edwards, built the Upi Agricultural School in 1919 and invited the Episcopal Church to do mission work among the Tiruray in 1926. Today, most Tiruray Christians are Episcopalian.

Anthropologist Stuart A. Schlegel, whose publications are primary sources of information on the Tiruray, was a missionary. In 1964, as head of the Episcopal Mission of St. Francis of Assisi in Upi, he formed the Tiruray Cooperative Association (TICOA), which provided the Tiruray with facilities to store their crops and helped Tiruray farmers obtain titles for their land, of which they had been steadily dispossessed by homesteaders.

Tiruray Houses and Community

The inged is the largest Tiruray social unit, consisting of several families living in several dengonon or settlements, which are small, dispersed hamlets with up to 20 houses each. In turn, several inged are widely scattered throughout the mountains and along the coast, about 20 kilometers from one another. Within a settlement, several Tiruray houses are usually clustered together within the clearing. In general, Tiruray settlements are located near water sources and are given names derived from the prominent features of the physical surroundings, such as rivers, creeks, or springs.

|

| Houses near the Cotabato River, 20th century (Photo courtesy of John Tewell) |

The Tiruray house in the 19th century was built by a culture group whose way of life was determined by swidden farming. Thus, their home was no more than a “field hut” (Tenorio 1970, 366), with thin posts stuck a few inches into the ground, easily brought down by the winds. The flooring of the house was made of tree bark, and only a few used bamboo. There was no wall, only hangings of bark or fronds of rattan. Such a design was necessary for defense: the occupants could see the enemy clearly when they raided, enabling the Tiruray to shoot their arrows.

Another structure put up by the Tiruray is the kayab (small guard hut), built above the swidden field once the swidden is fully planted to the first crops. From the kayab, one may have a complete commanding view of the plants. The kayab is used as sleeping quarters and also as shelter from the hot sun. The swidden hut is about 2 by 2 meters, supported by at least four low stilts or posts, and has walls and a roof made of rattan. The wood used for the kayab is gathered from the forest or set aside when the clearing was made. The bark of the menurer tree serves as flooring. Rattan vines are used to lash together the entire structure.

In recent years, the Tiruray traditional house has been more steadily built, though still small, measuring some 3 by 5 meters. Wood and bamboo are the main construction materials for the body, and grass is used for the roof. Five or six liley (main posts) made of round hardwood hold up the structure. The feher (roundwood pole studs), about a dozen or more, surround the house. To these are attached the four serinan (roundwood pole beams), which, with the main posts, define the rectangular shape of the Tiruray house. The studs are fixed on four large bamboo lengths, serving as sara feher (base). A short distance above the ground, two fadal (roundwood girders), one on each length of the house, serve to connect the posts as well as support the series of bekenal (roundwood floor joists). An interesting feature is the tenuwe (door) made of bamboo frame, which is hinged at the bottom and thus folds out to the ground when opened. On another side of the house is another opening to which a gadan (notched log ladder) leads up. The diding (walling) goes around the house and is made of cracked bamboo, which is also the material for the saag (flooring). The salagunting (roundwood pole trusses) start from the beams and end just below the luntud (ridge roll). The kesew (roundwood rafters) and the berewar atef (purlins) make up the framework of the roof. To these are attached the atef (grass roofing). Finally, along the center purlin known as titay berungan on the roof ridge, there are usually roof ornaments of a religious nature. These are called fakang, salag buwen, and kula-kula.

In certain settlements, especially the acculturated ones, the traditional ramp window-doors, which are hinged, are giving way to Western-style swing-type doors, while the notched log ladders have been replaced by the lowland-type pole step ladder. Also, the religious ornamentation has been completely eliminated from the roofs.

Today, the first structure that greets visitors of the municipality of Upi is a roundabout at the center of the town of Nuro, its capital. In the middle of this roundabout is a monument composed of three human figures who represent the tri-people of Upi: the lumad (Tiruray), Muslim (Moro), and Christian. The monument emphasizes the importance of harmony between these three groups of residents.

Tiruray Traditional Attire

Early Tiruray apparel, including the weaponry that formed part of their attire, differed according to place of habitation. Thus, men who belonged to the “downstream people,” that is, those who lived near the towns and the Maguindanao population, wore long trousers and waist-length shirts. Their weapons consisted of a kris carried at the side, a spear held like a walking stick, a fegoto (wide-bladed kris) slung over the shoulder, a dagger tucked at the waist, and either a round shield called taming or an elongated one called kelung. Those who lived along the coast wore G-strings and shirts. Their weaponry consisted of benongen, a blade similar to the kris but smaller than the fegoto; a spear; and a bow and a quiver of arrows, which even children carried around. These arrows were tipped with kemendag, the poisonous sap of a certain tree. The men from the mountains wore short trousers and the same cut of shirt as the other groups, although they tended to have less body covering despite their mountain residence. Their weapons consisted of the kris, spear, and bows and arrows.

|

| Tiruray women in native dress (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Tiruray women, in general, wore a sarong called emut, made from abaca fiber. They wore shirts like the men, which were nearly of the same general cut, except that the women’s blouse was form fitting, while the men’s shirt hung more loosely. Since Tiruray women never developed the art of weaving cloth, their dress material came from outside sources. The women also wore rinti, a series of brass bracelets of different sizes, extending from the wrist and up the forearm; a brass cord and belt decorated with small jingling bells which they wore around the wrists; brass anklet rings, necklaces of glass beads and colored crystals; and the kemagi, a necklace made of gold. They also sported wire earrings from which hung small shell ornaments. The Tiruray women were never without a knife and a small basket that they carried wherever they went. Both men and women wore the sayaf, a shallow conical hat made from buri, worn as a protection against the heat of the sun.

These clothing and weaponry of the late 19th century were worn by the nonacculturated Tiruray. However, the downstream people of the same period were already dressed in the manner of the Maguindanaon, who were the nearest source of acculturating influences. In recent times, these acculturated Tiruray have adopted “modern” ways of dressing, while the Tiruray of the interior may still wear the kind of dress their forebears did, but without the panoply of weapons which used to be a normal part of their habiliments.

Tiruray Arts and Crafts

|

| Tiruray woman weaving baskets and hats, 2016 (sox.ph) |

The Tiruray have not developed the arts of traditional cloth weaving, metalcraft, and pottery, but excel in basketry. They are, in fact, one of the most accomplished basket weaving groups among the country’s cultural communities. In recent times, many traditional patterns and designs in Tiruray basketry have incorporated “contemporary” adaptations, even borrowing from other ethnic styles because of the market. Nevertheless, even in “modern” designs, the Tiruray’s skill in traditional basketry shows, as evidenced by the evenness of execution and the symmetry of shapes. Before being split for weaving, the bamboo material is first smoked black. These blackened strips of bamboo are then combined with unsmoked, uncolored strips of natural bamboo in a weave pattern that can have multiple variations.

In the 1960s, traditional carrying baskets with or without covers were “developed for sale to a tourist market” (Lane 1986, 187), and some Bontok baskets were even brought to the Tiruray basket makers by the Episcopalians. As a result, some features of Bontoc basketry were adopted by the Tiruray, such as a bamboo foot in the carrying basket and fitting covers on small boxes with splitnitobraids, which served as both stopper and finishing edge. Other types of baskets developed by the Tiruray through this process of adoption were nested boxes, open baskets with square rigid foot rims, nested sets of open basket planters, and trays. A nested set of open basket planters may have 12 pieces in all, ranging from the largest with a height of 40 centimeters, to the smallest with a height of 22 centimeters. No mold is used, and yet the proportions are remarkably exact, each basket snugly fitting into the next larger one.

Another complicated piece of basketry is the coined storage jar, which uses various shades of nito. The variation in shades results in a subtle pattern, even without a consistent design. The handle is made from a length of split rattan bound with nito strips in alternating shades of natural brown and dark brown.

Developments in Tiruray basketry have been a function of the economic situation. More and more Tiruray turned to making baskets, not for any domestic use, but for the tourist and export market. Basketry, formerly a household art, has become a source of cash income. Demand was high for the Tiruray baskets in the late 1960s and 1970s.

Tiruray beliefs and practices have been incorporated into their weaving tradition. They believe that the varying shades of nito are a result of its exposure to the moon: nito is light when it grows on a moonlit night, and dark when it grows on a moonless night. The moon, it is believed, also determines the quality and durability of the bamboo used for basket weaving. To prevent it from rotting quickly, the Tiruray harvest bamboo on moonless nights.

Monom, the Tiruray basket weaving tradition, continues to this day with the aid of local groups like the Lumad Development Center and international project funders like the IPDev, which is supported by the European Union. Traditional baskets are still of the same materials of old, like nito, pawa (a thin and light kind of bamboo), and teel (a kind of rattan) for rims. These baskets are still being used in Tiruray households. Tiruray baskets include biton, which dangles from the forehead to the back with a strap and is useful for harvesting crops like corn, rice, and vegetables. A covered biton is a senafeng, which is for storing seeds. Tefaya is the winnowing basket.

Tiruray weave designs include doh tuwol (macopa seed cut in half), sebanga igor (one animal biting the tail of another), and the belinsuwang (movement of a rocking chair). Some designs are taboo, such as the human form, which can bring bad luck. Other designs are restricted only to specific individuals in particular circumstances, such as the moto teniboh, to be woven only by a person who has killed another, and the taang-taangan,which is wovenonly by one who has run off with another’s spouse.

All iron tools used by the Tiruray have been procured through trade with the Maguindanaon. In recent years, however, a few Tiruray have been learning the art of blacksmithing from their Maguindanaon neighbors, one of whom fashioned the Tiruray’s first bellows forge, which was needed to turn out rudimentary iron blades.

Tiruray Literary Arts

Riddles

Tiruray literature includes riddles, myths, legends, and animal stories. Examples of Tiruray riddles, gathered by the Department of Education, are the following:

Antok antok sa beem

Rowo timan roge’ng se’gule

Ile’nge’n, ge’gumah de’b laway yo. (Mata)

(Riddle riddle

Two round fruits

Turn them once, and they reach the sky. [Eyes])

Antok antok sa beem

Jor-jori kray, talufutot- I to – o? (Kasing)

(Riddle riddle

You pull the vine, it’s the tree that turns. [Trumpo or

top])

Myth

The Tiruray creation myth centers around a female deity called Minaden, who shaped the world and the first creatures living on it. She fashioned human beings from mud. Having done this, she placed the sun between the earth and the sky, and brought forth daylight. The skyworld is believed to be divided into eight layers, with the topmost layer occupied by Tulus, Minaden’s brother. Tulus was also known by other names such as Meketefu (the “unapproachable”) and Sualla. The first two human beings created by Minaden began to grow, but after some time, they had not yet begotten any offspring. Meketefu came down from the skyworld and saw that the male reproductive organ was as small as a tiny red pepper, while that of the female was as big as a snail shell. Furthermore, their noses were upside down so that whenever it rained, they caught water, making the two human beings sick. Meketefu decided to create his own clay figures of a man and a woman. Using an old bolo, he struck the female figure, wounding her where the legs joined together. As he did so, the handle of his bolo flew off and stuck to the middle part of the male clay figure. He also turned their noses right side up so they would not take in rainwater. Soon after, the two creatures were able to bring forth a child into the world. But no food was available to nourish themselves and the child, who eventually died. But the world had no soil, and the child could not be buried. And so the father begged the god Meketefu to give them soil. Much later, various types of vegetation sprouted from the plot of earth where the child was buried. One part of the plot gave forth plants and lime for chewing. The child’s umbilical came out as a rice stalk. Its intestines were transformed into sweet potatoes. The head became the taro tuber. The hands turned into bananas, the nails into areca nuts, the teeth into corn, the brains into lime, the bones into cassava, and the ears into betel leaf.

|

| Minaden, Tiruray female deity who created the earth (Illustration by Ray Sunga) |

The Tiruray have culture heroes in their mythology, such as Lagey Lengkuwos, the mightiest of them all. It is said that he could talk while still in the womb of his mother. It was he who recreated the earth, because the one originally made by Minaden was all forests and rocks, a barren world. In Sigayan’s account, women epic chanters told stories about Lagey Lengkuwos, Metiyatil Kenogon, Bidek, and Bonggo, who were described as among the first people on earth who were not gods but were followed and trusted by the earliest Tiruray in the same way that they trusted Tulus himself. These epic heroes now inhabit the realm of the spirits.

Another myth of the second creation is attached to the life of Lagey Lengkuwos. According to this myth, people during the days of Lagey Lengkuwos were undergoing hardships with their farming. They did not yet have the right knowledge of farming, which included knowing when the winds would be right for burning, when the rains would come to signal the start of planting, and how to tell good and bad omens that could spell the difference between success and failure in swidden agriculture. It is said that Lagey Lengkuwos, who was the leader of all human beings in the world, was only too aware of the people’s predicament. Near his place, there was a settlement where six farmers lived. They had a pet bird, a forest dove known as the lemugen. The time came for Lagey Lengkuwos to lead his people to the celestial abode of Tulus, since their stay in the world was finished. But Lagey Lengkuwos, who indeed wanted a second creation of human beings in the world to clear the forests, did not want the next people to have such a difficult time farming. He asked two things of the six farmers: that they leave their pet bird lemugen behind so that it could give the necessary bird omen-calls for the next generations of swidden farmers; and that they live in the sky as constellations forever or for as long as there is a world peopled by swidden farmers. Since then, the lemugen bird has given omens to the farmers to let them know what to do and what not to do, while the six constellations have appeared regularly to signify seasonal changes that guided the people in the agricultural cycle of burning, planting, harvesting, and letting the land lie fallow.

Tiruray Legend: How Rice and Corn Came to Us and other Tales

|

| “How Rice and Corn Came to Us,” Tiruray legend (Illustration by Ray Sunga) |

The legend of “How Rice and Corn Came to Us” explains that in older times the Tiruray, represented by Kenogolagey and his wife Kenogen, ate only camote and cassava. One day, an old man visited them and told them about rice and corn, much better food than what they ate, but these can only be found in the castle of a fierce giant in the middle of the sea. Upon the advice of the old man, Kenogolagey sent his two friends, the cat and his dog, to get the food. The two agreed, swam for two days in the sea, and finally discovered the rice and the corn lying in two heaps beside the giant’s legs. As the giant slept, the cat took rice grains into its mouth and the dog a pair of corn ears. Swimming back to shore, the dog dropped his corn ears into the bottom of the sea, and the cat, unable to help him because it had rice grains in its mouth, delivered the grains to the shore, and dove back for the ears of corn. The dog took the rice grains and headed for home, claiming glory for itself. The cat survived and found its way home with the ears of corn. The cat revealed the truth about the dog, and the dog jumped at the cat to tear it apart, but the cat nimbly ran away. Although the adventure brought rice and corn to the Tiruray, it also caused the permanent enmity between dogs and cats.

Like the pilandok (mouse deer) of other indigenous groups, the turtle in Tiruray tales is a wily and naughty character. In “The Turtle and the Monkeys,” the turtle meets up with the cock who is proud that he no longer has to hunt because he has found a pile of grains somewhere. The turtle, envious at this, tells the cock that he has red eyes, a sickness which could lead to death. Frightened, the cock follows the turtle’s prescription. He goes to fetch the sap of the tegef and puts this on his eyes. The sap hardens and the cock, in panic, runs and falls, and ends up with his head in the hole on the ground. The crab that lives in the hole eats the fragrant sap on the cock’s eyes, allowing it to go free to exact vengeance on the turtle. Meanwhile, the turtle playfully swings at the tip of a rattan leaf. He persuades the monkey to do the same, but the latter, who is heavier, falls over the cliff and dies. The turtle promptly collects the brains, ears, and heart of the monkey. Later, another monkey, Dakel-ubal, who is busy planting palay in his kaingin, asks the turtle for some betel chew. The monkey obliges, passing off the remains of the dead monkey as the betel chew ingredient. Dakel-ubal recognizes the monkey remains, calls on all the monkeys, and sentences the turtle to drowning. In the water, the turtle laughs at the monkeys’ ignorance. Angry, the monkeys ask the creature Ino-Trigo to sip all the water of the river into his belly. The creature does so, and the turtle is revealed hiding beneath some dead branches. Seeing his enemy, the cock swoops down on the turtle to peck out his eyes. The cock misses and slashes instead the stomach of Ino-Trigo. The stomach bursts, and all the water rushes back into the river, drowning the cock and all the monkeys.

A female supreme deity, Fulu-fulu, is the head of the Tiruray pantheon, as narrated in the Tiruray epic Berinareu. Directly under Fulu-fulu are three lundaan (secondary deities): Menggerayur, her sister; Menemandai, the creator of the world, humankind, and their sources of livelihood; and Fengonoien, her double. Below the lundaan are the meginaleu, supernatural beings who are either good or bad. The good beings are followers of their four superiors; the bad beings meddle with the affairs of human beings, particularly shamans, whom they seek to prevent from entering the other world.

Berinareu takes 80 hours to chant. Its theme is sefebenal, literally “the right to seek revenge,” but in practice it means the right to restore a right transgressed by their common enemy. Terasai (suffering) is what the people must undergo to attain happiness, and in this epic, it is represented by the hard labor of swidden farming.

The hero of Berinareu is the great shaman Lagey Lengkuwos, also known as Seonomon, who undertakes several journeys through various dimensions, including death, before he finally leads his people to the Region of the Great Spirit, which is also the land of happiness and where the supreme deity Fulu-fulu resides. The story begins with Seonomon’s rescue of his betrothed, Seangkaien, from her abductors. Complications arise when Seangkaien learns that Seonomon’s brother has arranged a marriage between Seonomon and Linauan Kadeg. An angry Seangkaien ends her betrothal to him. Upset, Seonomon journeys through several dimensions until he meets Fulu-fulu, from whom he asks for a golden bracelet with eight knots, which will take him from this world to the next. Fulu-fulu gives it to him, with the warning that it is only for Seangkaien, because she is destined to be his partner in leading the Tiruray people to the land of happiness. He swears he would rather die than take betel nut chew from Seangkaien ever again. Back on earth, Seonomon is smitten by Linauan Kadeg, and he gives her the golden thread for her tamuk or bride-price. Seangkaien and her allies, including Seonomon’s own sisters, wage war and defeat Seonomon’s followers. She retrieves the golden thread from Linauan Kadeg. Seangkaien and Seonomon reconcile, but when he accepts a betel nut chew from her, he dies. Seangkaien journeys through several levels to plead with the deities not to receive Seonomon; hence, she revives him. They return to Mount Lengkous, the land of the Tiruray, where they first prepare for their journey to the land of happiness by engaging in swidden farming. On the eighth day, Seonomon dances “with stamping feet and arms outstretched.” The lundaan send them a piece of land that will fly them to the other world. Seonomon tricks the malevolent gatekeeper of that world into letting them in; they wash their bodies away in the Ligoden River; and Fulu-fulu finally welcomes them into the land, where they “have no more to worry” (Wein 1989).

In a sequel to this Tiruray myth of creation, the Great Spirit creates another group to take charge of the landleft behind by Seonomon and his followers. The great shaman Lagey repeats Seonomon’s feat and, using the epic of Berinareu as guide, also leads his people to the other world . The Great Spirit creates more Tiruray, who become “the ancestors of the people alive today” (Schlegel 1999, 82).

Tiruray Music

Video: TEDURAY Traditional music and Dance

Among the many Mindanao lumad groups, the agung, a suspended bossed gong with a wide rim, is the most widely distributed brass instrument. The most developed agung ensembles are those of the Tiruray and the Bagobo. The Tiruray kelo-agung or kalatong ensemble, composed of five shallow-bossed gongs in graduated sizes, is played by five men or women. The smallest of the gongs, the segarun, leads with a steady beat, and the four others join in with their own rhythms. The kelo-agung is used in agricultural rituals, weddings, community gatherings, victory celebrations, curing rites, rituals for the dead, and the entertainment of visitors. The musical pieces played on the kelo-agung include antibay, fotmoto, liwan or kanrewan, turambes, and tunggol bandera. Similar to the gong ensemble is the wooden xylophone with eight pieces of wood on a low stand, played by three persons. A smaller version is the hanging wooden xylophone with five pieces of wood, played by one man.

|

| Tiruray woman playing a wooden xylophone, 1993 (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

There are several other musical instruments used by the Tiruray in everyday and ritualistic occasions. The kubing is a mouth harp made from a special variety of bamboo. The idiophone is known by this name in several Muslim and lumad groups in the south. Among the Tiruray, the kubing is used for courtship as well as for entertainment. The togo is a five-stringed bamboo tube zither, which may play the same pieces heard on the gong ensemble. It is a solo instrument, but several zithers are often played all at once. This chordophone is played by two women. One of them holds one end of the bamboo tube while playing a melody on three strings. The other woman holds the other end while playing a drone on the two other strings. This instrument is important because it can substitute for the kelo-agung. It shares a similar function and may be heard during the same occasions when the kelo-agung is played. In addition, the togo accompanies songs and dances. Meanwhile, the fegerong is a two-stringed lute with 5 to 11 frets. This instrument is used for courtship and entertainment. Part of the repertoire of the fegerong is the musical pieces laminggang and makigidawgidaw.

|

| Tiruray man playing the lute, 1993 (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

The two bamboo flutes of the Tiruray are the falendag and suling. Both have three finger holes and a thumbhole. The falendag is the lip-valley or deep-notched bamboo flute. Its construction makes possible lip control of the air flowing into the tube, allowing for a degree of tonal control and sensitivity not possible with flutes of similar dimension but with differently shaped blowing holes, such as the suling or short ring flute. The suling is a duct flute, the sound of which is produced by adjusting the ring on the mouthpiece in relation to the blowing hole. The pitch of the suling has a higher range than the falendag’s and can express specific emotions, such as the sobbing of a girl who has just been told by her parents that she is about to be married.

|

| Tiruray man playing a hanging wooden xylophone, 1993 (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

The Tiruray have a wide range of songs for various occasions. The balikata is a song with improvised text, sung to traditional melodies; it could be a melodic pattern used for debates, pleading of cases, plain conversation, or it could be a very specific song about the singer’s experience with the field researcher’s tape recorder. The balikata bae is a common lullaby, in which the mother tells the child to sleep soundly and grow up as strong as the rattan vine. The lendugan is a love song, a poetic description about the beauty of courtship, comparing it to flowers; it also refers to a type of melody or a certain mode, such as a lullaby or cradle song. Some lendugan also describe the lifeways of the Tiruray. The binuaya is a narrative song that tells stories of great events in the distant past. The siasid is a prayer-song invoking the blessings of the god Lagey Lengkuwos and the nature spirits Serong and Remoger. The foto moto is a teasing song performed during weddings. The meka meka is a song of loyalty sung by a wife to her husband. The melodies of songs like foto moto and meka meka are often rendered on the kelo-agung and other instruments.

Tiruray Folk Dances

One of the more notable Tiruray dances is the mag-asik, literally, “to sow seeds,” performed by girls in Nuro, Cotabato. The dance begins with a large piece of bright-colored cloth or material placed on the ground or on the middle of the floor. The women go around this cloth with small, heavy steps, their arms and hands moving about in graceful fashion. The dancers wear tight long-sleeved blouses of shiny material, in various colors, and a peplum along the waist. Tiruray women favor bright red, yellow, blue, orange, purple, and black. They wear a patadyong, a skirt that goes all the way down to their anklets. They may also wear a necklace made of gold, beads, or old silver coins, which goes all the way around the neck and reaches down to the waist. The rich wear metal belts about 15 centimeters wide. The sarong hangs on the left shoulders of the dancers, and only their lower lips are painted.

There are two other types of Tiruray dance: the kefesayaw teilawan, in which the dancers imitate bird movements; and the tingle, a war dance, in which two rival suitors fight for the affections of a maiden. Both dances are performed during wedding celebrations and other festivities.

In 2003, during the term of Upi Mayor Ramon Piang Sr., a festival called meguyaya, which is the Tiruray thanksgiving feast, was organized to celebrate the local cultures. The weeks-long festival included beauty contests, a trade fair, and street dancing competitions. The Meguyaya festival won second place in the 2014 Aliwan Fiesta, a national showcase of festivals from around the country and sponsored by several groups, including the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP).

Tiruray People in Media Arts

The municipality of Upi, despite its distance and isolation from urban centers, has a community radio station that advocates peace. Before 2002, only radio stations in nearby Cotabato City served Upi. That year, however, the local government, under Tiruray Mayor Ramon Piang Sr., partnered with DXMS in Cotabato City to air a weekly 30-minute radio program. With outside grants and local government funds, Upi embarked on a training program to start its own community radio, with three objectives: first, that the community radio serve to publicize and explain the local government’s programs and projects; second, that it help educate residents of Upi on peace, and promote a culture of understanding between Tiruray, Christians, and Muslims; and third, that it serve as the residents’ means of communicating their concerns to the local government.

On 8 February 2004, the community radio station DXUP FM was formally inaugurated, complete with its own building, a 300-watt transmitter, and some 35 trained volunteers to take charge of technical, broadcast, and programming operations. DXUP FM can also be heard in nearby areas of Maguindanao and in Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, Lanao del Sur, and even as far as Baganian point in Zamboanga Sibugay. It operates from 5:00 AM to 9:00 PM, with around 31 radio programs per week, consisting of “news, barangay affairs, moral values development, and livelihood programs,” some of which are hosted by the local officials of Upi themselves. In 2007, three years after it started operations, DXUP FM received a special citation from the Titus Brandsma Award-Philippines for “promoting faith and inter-peace dialogue among the Upi residents” (Cureg 2008).

Sources:

- Abinales, Patricio N. 2012. “Let Them Eat Rats! The Politics of Rodent Infestation in the Postwar Philippines.” Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints 60 (1): 69-101.

- Annual Report of the Philippine Commission. 1900.

- Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao.2013. “ARMM History.” Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao Official Website. http://armm.gov.ph/history/.

- Cabrera, Ferdinand B. 2011. “Camera-Toting Priest from Mindanao Awarded Ninoy and Cory Aquino Fellowship.” Minda News, 12 July. http://www.mindanews.com/uncategorized/2011/12/07/.

- “The Comprehensive Agreement on the Bangsamoro.” 2014. Official Gazette. Accessed 8 August. http://www.gov.ph/2014/03/ 27/document-cab/.

- “Cooperative Formed in Philippines.” 1964. Episcopal Press and News Digital Archives 1962-2006. episcopalarchives.org/cgi-bin/ENS/ENSpress_release.

- Cureg, Elyzabeth Flores. 2008. “Lesson Plan for Change: A Story of Inspirational Leadership from Upi, Maguindanao.” Center for Local and Regional Governance. http://www.academia.edu/5887248/.

- Demetrio, Francisco, Gilda Cordero-Fernando, and Fernando Zialcita. 1991. The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.

- Department of Education – ARMM. 2013. “Workshop on Learning Framework for Teduray Children Done.” DepEd. ARMM. http://deped.armm.gov.ph/2013/07/.

- Department of Education – Region XII.2013. “Kulturang Socssksargen: Teduray Scope.” Learning Resources and Research Publications. http://depedroxii.org/download/learning-resources/ research-publication/.

- Department of Public Works and Highways. 2011. Region 12-News Archive. http://www.dpwh.gov.ph/ offices/.

- Estremera, Stella A. 2014. “Monom: Teduray Weaving Tradition.” Sun Star Davao, 1 February. http://www.sunstar.com.ph/weekend-davao/2014/ 02/01/.

- Galing Pook Foundation. 2004. “Tri People’s Way of Conflict Resolution.” Best Practices in Local Governance. http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/eropa/unpan031891.pdf.

- Institute for Autonomy and Governance. 2014. “The Origin of the Tedurays.” Accessed 8 August. http://www.iag.org.ph/ index.php/ipdevnews/479.

- International Crisis Group. 2011. “The Philippines: Indigenous Rights and the MILF Peace Process.” http://www.academia.edu/1185485/.

- Jocano, F. Landa. 1975. Philippine Prehistory. Quezon City: Philippine Center for Advanced Studies, University of the Philippines.

- Kaufman, Stuart J. 2011. “Symbols, Frames, and Violence: Studying Ethnic War in the Philippines.” International Studies Quarterly 55: 937-958.

- Lane, Robert. 1986. Philippine Basketry: An Appreciation. Manila: The Bookmark, Inc.

- Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2014. Teduray. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 17th ed. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/17/.

- “Lumad Basakanon Reclaims Aliwan Fiesta Crown with Fourth Win.” 2014. Inquirer Lifestyle. Accessed 9 August. http://lifestyle.inquirer.net/159372/.

- Maceda, Jose. 1980. “Philippine Music: Indigenous and Muslim-Influenced Traditions.” In The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians 14, edited by Stanley Sadie, 636-650. London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd.

- “Moros, Lumads Reaffirm Kinship in Support to GPH-MILF Peace Talks.” 2013. Minda News, 27 December. http://www.mindanews.com/top-stories/2013/12/ 27/

- Municipality of Upi. “Upi’s Historical Background.” 2013. Upi Official Website. http://www.upians.com.ph/lgu-upi/index.php/socio-economic-profile/89.

- Notre Dame University Research Center. 2005. “The Case of the Teduray People in Eight Barangays of Upi, Maguindanao.” Notre Dame University. http://www.scribd.com/doc/129001576/URC-2005.

- Office of the Presidential Adviser on the Peace Process. 2012. “Transition Commission Members’ Profiles.” http://www.opapp.gov.ph/sites/default/ files/ 134142320.

- Patanñe, E.P. 1977 “Hunters and Trappers.” In Filipino Heritage: The Making of a Nation 1, edited by Alfredo R. Roces. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc.

- Peralta, Jesus T. 1988. “Briefs on the Major Ethnic Categories.” Workshop Paper on Philippine Ethno-Linguistic Groups. International Festival and Conference on Indigenous and Traditional Cultures, Manila, 22-27 November.

- Pfeiffer, William R. 1975. Music of the Philippines. Dumaguete City: Silliman Music Foundation Inc.

- Pronouncing Gazetteer and Geographical Dictionary of the Philippine Islands. 1902. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Regional Map of the Philippines – XII. 1988. Manila: Edmundo R. Abigan Jr.

- Reyes-Tolentino, Francisca. 1946. Philippine National Dances. New York: Silver Burdett Co.

- Schlegel, Stuart A. 1970. Tiruray Justice. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- ———. 1979. Subsistence Economy of Traditional and Peasant Tiruray of Mindanao, Philippines. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- ———. 1979. Tiruray Subsistence: From Shifting Cultivation to Plow Agriculture. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- ———. 1999. Wisdom from a Rainforest: The Spiritual Journey of an Anthropologist. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

- Silvestre, Rodolfo A. G., Jr. 2004. “The Right Stuff.” Newsbreak Magazine, 29 March. http://archives. newsbreak-knowledge.ph/2004/03/29.

- Sunburst: The International Magazine 5 (5). 1977.

- Supreme Court. 2008. “Province of North Cotabato vs. Government of the Republic of the Philippines Peace Panel.” Supreme Court Judiciary. http://sc.judiciary.gov.ph/jurisprudence/2008/october2008/183591.htm.

- Tenorio, Jose (Sigayan). 1970. “The Customs of the Tiruray People.” Translated by Stuart A. Schlegel. Philippine Studies 18 (2).

- Trecero, Fernando C. 1977. Tiruray Tales. Manila: Bookman Inc.

- Wein, Clemens. 1989. Berinareu: The Religious Epic of the Tirurais. Manila: Divine Word Publications.

- Wood, Grace L. 1957. “The Tiruray.” Philippine Sociological Review 5 (2).

- This article is from the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Digital Edition. Title: Tiruray. Author/s: Edgardo B. Maranan (1994) / Updated by Jake Soriano, with contributions from Rosario Cruz-Lucero (2018). Publication Date: November 18, 2020. Access Date: September 21, 2022. URL: https://epa.culturalcenter.gov.ph/1/2/2378/

![Tiruray (Teduray) Tribe of Mindanao: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group] Tiruray (Teduray) Tribe of Mindanao: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgThJgpWfYshUMg0esbXg6qp90aTlEz4TkC_c2Xp8B_LIwv9s64SN7fzA7wMCzEsk8EyY0H-vg6CZ0zObQN251S8VID7SNos2OYvXfvun-Ina2aAnSwLI7sHo_yypRvdeP25LJSh3I_Y-GgR4XX2K5lxTClWljGrmNfgECqda6bzl3L3tf4vw/s16000-rw/Island%20Escape.png)

1 comment:

Thank you for doing this enormous amount of research work. You've found a huge number of very cool sources, and your blog deserves to be near the top of the search results for the Teduray in English.

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?