The Ilocano People of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Ilocos Region]

The narrow northwestern coast of Luzon directly facing the West Philippine Sea is the native domain of the Ilocano. Prior to the coming of the Spaniards, the coastal inhabitants were called Iloko, which derives from the prefix i, meaning “people of,” and lokong, referring to the low-lying terrain (Alvarez 1969, 143-149). The Iloko, therefore, are “people who dwell in the lowland,” as opposed to the Igolot who are people of the gulot or mountains, specifically the Cordillera mountain range. Ilocano is the Hispanized adaptation of the original name. Iluko refers to the language of the Ilocano.

The geographic depression of the Ilocos region is largely due to the hilly feature of the landscape hemmed in by the peaks of the Malaya range that merges with the higher ridges of the Gran Cordillera Central. The topography of Ilocos projects the appearance of a series of salad bowls rimmed by rolling hills on a cramped table. Being contained in a relatively bare coast, the region is vulnerable to extreme climatic changes. During the dry spell, the land is particularly parched because the eastern ridges prevent the inflow of wind and precipitation from the eastern valleys and uplands.

This coastal region combines starkly contrasting terrains. At its southern sprawl in Pangasinan are fertile alluvial flats that extend from the coast of Lingayen Gulf to the foothills of the Cordillera and the Caraballo Sur mountains. La Union and Ilocos Sur towns alternate between hilly and flatland. Ilocos Norte landscape interweaves alluvial plains, hillocks, and deserts; but toward the northern tip, in Pagudpud, the wooded mountains tower directly over the large area situated in the hinterlands occupied by other cultural minorities who have been, to a large extent, acculturated to the Ilocano lifeways.

As of 2000, the Iluko-speaking people number 6,938,920, or almost seven million, constituting 9.07% of the total Philippine population of 76,504,077, thus making them the third biggest ethnolinguistic group, after Tagalog and Cebuano. Although the Ilocano people are widely dispersed throughout the country, if not the world, the largest concentration of their population is still to be found in their original home provinces, where they number almost two million, broken down as follows: 658,587, which is the total population of Ilocos Sur; 741,906, the total population of La Union; and 568,017 in Ilocos Norte, where they constitute 93% of a total population of 594,206, the other 7% comprising the Kankanaey, the Isneg, and the Tagalog (NSO 2010).

However, the Ilocano have become the dominant group as well in their neighboring provinces where they have emigrated: In Quirino, 72% or 106,640 of the population, are Ilocano; in Abra, 71.9% or 150,457; in Isabela, 68.71% or 883,982; in Cagayan, 68.7% or 680,256; in Nueva Vizcaya, 62.3% or 228,027; and in Apayao, 50.82% or 49,328. There are other provinces in northern Luzon where they constitute the majority, or if they appear to be the minority in proportion to a province’s total population, they are the largest group in real numbers because the rest of the province’s population is divided among other ethnic groups: In Pangasinan, they are 44.25% or 1,076,219; in Tarlac, 40.9% or 436,907; in Nueva Ecija, 19.3% or 319,858; in Zambales, 27.5% or 118,889; in Baguio City, 44.5% or 111,132; in Aurora, 31.43% or 54,557; in Benguet, 13.4% or 43,984; in Kalinga, 24% or 41,633; in Ifugao, 13.7% or 22,171; in the Mountain Province, 6,968; and in Batanes, 149 (NSO 2000; 2010).

In central and southern Luzon, including the National Capital Region (NCR), also known as Metro Manila, they make up almost half a million, dispersed as follows: Bulacan, 24,159; Bataan, 11,259; Pampanga, 9,996; Angeles City, 3,680; and Olongapo City, 2.54% or 8,842. They are dispersed in the NCR as follows: Quezon City, 5.2% or 112,258; City of Manila, 49,831; Caloocan City, 44,487; Valenzuela City, 15,092; Pasig City, 13,668; and NCR, 15,657. They are in the southern Tagalog region, also known as CALABARZON, such as in the provinces of Rizal, 37,278; Laguna, 16,692; and Quezon, 2,146. In the MIMAROPA region: Occidental Mindoro, 26,766; Oriental Mindoro, 10,728; Marinduque, 237; and Palawan, 24,902 (NSO 2000; 2010).

The government census reflects about 200,000 Ilocano in Mindanao. This significant number in that region reflects the national government’s homestead program, which began during the Spanish colonial period, and the consequent displacement of that region’s indigenous peoples, including the Muslim groups: in Sultan Kudarat, there are 88,160 Ilocano or 17.17% of the province’s population; in Cotabato, also known as North Cotabato, 65,832; in Sarangani, 19,106; in Zamboanga del Sur, 14,086; in Maguindanao, 8,106; in Lanao del Sur, 5,300; and in Lanao del Norte, 563. By mid-2016, the Ilocano people would number at least 9.27 million in the Philippines, at a ratio of 9.07% of a projected total Philippine population of 102,250,133 (NSO 2000; 2010; WPR 2013).

In 1998-2005, Ilocano emigrants to Hawaii, numbering 31,346, made up at least 50% of the 62,366 Filipino emigrants in that state. With a current Filipino population of 300,000 in this same state, one may surmise that at least 150,000 of them are of Ilocano origin. Ilocano overseas workers worldwide number at least a quarter of a million, or 253,350. From the three home provinces of the Ilocano come at least 133,850 of the country’s overseas workers: 24,444 from Ilocos Sur; 94,111 from Ilocos Norte; and 15,295 from La Union. Many more come from the neighboring provinces with a significant Ilocano population, such as Pangasinan, which has 64,106 overseas workers; Cagayan Valley, 44,630; and Nueva Vizcaya, 10,764 (Fonbuena 2014; NSO 2000; 2010).

History of the Ilocano People

At the early stage of Spanish colonization, the maritime trade posts in Ilocos were linked by sailboats and by a lingua franca called Samtoy, a contraction of sao mi’toy meaning “our language here.” The Augustinian Andres Carro noted in his 1792 manuscript that Samtoy was used so extensively that the Spanish colonizers, led by Salcedo in 1571, learned the language because it was spoken by the people from Bangui to Agoo. Eventually the natives called it the Ilocano language.

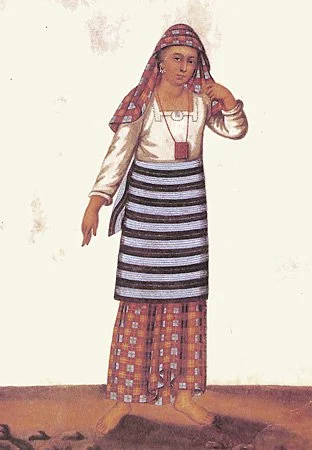

|

| Damian Domingo, Un Yndio Natural de la Provincia de Ylocos, circa 1830 (Paulino and Hetty Que Collection) |

While many people in Abra Valley trace their ancestral links to lowland communities, they are in fact dwelling in the Cordillera range. The prehistoric migration and trade routes between this valley and the coast are the rivers interlinked with upland horse trails.

|

| Damian Domingo, Una Yndia Ylocana, circa 1830 (Paulino and Hetty Que Collection) |

In the 16th century, the Ilocano who lived in the port towns of Candon, Laoag, Vigan, Lingayen, Bolinao, and Sual were already trading with the Chinese. In 1582, Spanish expeditionary forces came upon the natives of the Ilocos, whom they described as similar in appearance, attire, and manner of living to the mountain dwellers and those of the southern islands, specifically the Pintados (de Loarca 1903).

When the Spaniards, led by Juan de Salcedo, arrived in 1573, the tight-knit trade posts of the Ilocos put up a fierce resistance against the invaders; in retaliation, Salcedo and his men destroyed over 4,000 houses in just that year. The depopulation was such that authorities in Mexico were afraid that the Ilocos would not recover in six years or a lifetime. Salcedo subsequently became the first encomendero of the Ilocos. He founded near the old Vigan trade post, the Villa Fernandina, which he named after the Spanish king’s infant son. After he died in 1576, the villa was ravaged by an epidemic. It then fell under the administration of Vigan, and later was incorporated into the town.

All the riverside trade posts from Lingayen to Bangui were the first to be transformed into pueblos organized along the typical grid pattern radiating from the church, plaza, and town hall. From the 17th to the 19th centuries, Spanish control was established systematically through the conversion of the natives. The process of reduccion, or of keeping the people “under the bells,” forced other natives to migrate to the hinterlands and remote valleys, where they intermingled with the Igorot. For many generations, these new mixed settlements provided a refuge from Spanish raids and headhunting forays of the mountain dwellers until the latter were also converted by the missionaries.

|

| Scene from Lino Brocka’s Dung-aw, starring Armida Siguion-Reyna as Gabriela Silang, 1975 (CCP/Lino Brocka Collection) |

In reaction to the Spanish imposition of more and more onerous tributes and monopolies on the Ilocano, several revolts erupted from the 17th to the 19th centuries. In 1589, only 13 years after Salcedo’s death, the people of the northern town of Dingras rose in arms against the colonizers. In 1660, another revolt took place in San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte, led by Pedro Almazan, who had been inspired by the Malong Rebellion in Pangasinan. But the most renowned Ilocano revolt was that one led by the couple, Diego Silang and Gabriela de Estrada, from 1762 to 1763. This uprising is known today as the Ilocos Revolt because it drew participants not only from the provincial capital of Vigan but also from other towns. A simultaneous revolt, known as the Palaris Revolt and named after its leader, occurred in Pangasinan (Blair and Robertson 1906, vol. 49, 300).

The Ilocos Revolt can be divided into two independent but sequential events: The first uprising was led by Diego Silang (born 1730-died 1763), and the second uprising, by Gabriela de Estrada, also known as Gabriela Silang (born 1731-died 1763). At daybreak on 22 September 1762, on the day that the British invaded Manila, Diego Silang and 2,000 armed indios suddenly appeared at the residence of the alcalde mayor (provincial governor), whom they were intent on killing. They represented various sectors and classes, not only of Vigan but also of the neighboring towns, particularly Bantay, Santa Catalina, and San Vicente in Ilocos Sur. After the governor’s forced departure, the uprising lasted for eight months, until Silang’s assassination on 28 May 1763, and even beyond, when it was revived by his wife Gabriela and her uncle Nicolas Cariño (Palanco 2002, 521).

The revolt was motivated by the following factors, besides the people’s hatred of the alcalde mayor: their vehement objections to the tribute and forced labor; the British conquest of Manila, thus exposing the vulnerability of the Spanish colonizers; and the ban on free commerce in the provinces (Palanco 2002, 521-522).

Government officials engaged in trade were prone to abuse their position of power by extorting from the native traders and producers. Seven years before Silang’s revolt, the alcalde mayor had been put on trial conducted by Judge Santiago Orendain, who was a close friend of Silang. Among the alcalde’s accusers were three members of Vigan’s principalia: Don Julian Miranda, Don Martin Crispin, and Don Juan Salazar. Legal measures to stop government corruption were futile, however. Hence, a few years later, the government decided to profit from illegal commerce by imposing a tax on it called the alcabala. Seven years later, during Silang’s revolt and the British occupation, Orendain took Silang’s side against the Spaniards and facilitated negotiations between Silang and the British. The three accusers of the alcalde became members of Silang’s advisory council during the revolt (Palanco 2002, 516-526).

In the next months, after putting down two Spanish counteroffensives, Silang established a government, which was shaky at best as he juggled the Spanish and the British threats as well as the Ilocano elite’s growing resentment of him. He had demanded of the Spanish government that all Spaniards and mestizos from the province be expelled, and he was mainly recruiting the timawa (common people) to his movement. Silang was assassinated by his erstwhile comrades Miguel Vicos and Pedro Becbec (or Bicbic), at the instigation of the Augustinian friars and with the blessing of Bp Bernardo Ustariz (Palanco 2002, 523-530; Blair and Robertson 1906, vol. 49, 163-168, 302).

Gabriela de Estrada and the venerable elder Nicolas Cariño continued Silang’s fight. On 23 June 1763, the rebels burned down the town of Santa Catalina to flush out Pedro Becbec, who had by then been appointed chief justice as a reward for Silang’s assassination. By mid-July, however, the Augustinians had mustered about 9,000 men from the north to recapture Vigan and demolish its visitas so that all the natives would be forced to move to Vigan “within hearing of the bells.” The colonialist troops, on their way to attack Bantay, burned all the barrios and killed everything that moved, including the residents who had taken sanctuary in the church at the advice of the Spanish commanders. The troops then forced these people out and executed them on the church patios (Palanco 2000, 530-531).

Pingit Island, now Puro Pingit, became a refuge for everyone fleeing the Spanish reprisals. Gabriela de Estrada retreated to the uplands of Abra, where she had the support of Tinguian warriors armed with bamboo lances and amulets. The colonialist forces giving chase engaged the rebels in a battle at Sitio Banaoang, between Ilocos Sur and Abra, and lost 35 troops. However, on 20 September, colonialist troops from Cagayan, led by Captain Manuel de Arza, quelled the rebellion with their superior firepower and executed Gabriela de Estrada, together with 90 others, on the gallows. The burial record of Diego Silang’s widow reads: “Doña Gabriela de Estrada, viuda de Diego Silang, natural de esta ciudad, del barangay de Endaya” (Palanco 2000, 531-532). The notable clans of Vigan who had supported the Silangs left town. A monument that had been erected at Bantay, Ilocos Sur in honor of the assassin Vicos was replaced by another to honor Diego Silang.

After Governor-General Jose de Basco imposed the Tobacco Monopoly in 1781 to raise revenue for the colonial government, Ilocano farmers again mounted a series of uprisings in Bacarra and Laoag in 1788, led by Juan Manzano. This was followed by another revolt led by Lumgao, which had religious undertones and which eventually led to the split of the Ilocos province into Sur and Norte in 1822.

The first decade of the 19th century also witnessed the imposition of the Basi Monopoly. The decree banned, on pain of grave penalty and fine, the drinking of basi (sugarcane wine) not bought in government stores. Although the native wine is normally fermented at home, the Ilocano were forced to sell their produce at a low price to the stores, from which they then bought back the wine at a higher price. In 1807, a few years after the imposition of the monopoly, the Ilocano in the northern towns marched with raised bolos and bows and arrows, all the way to San Ildefonso near the capital town of Vigan. The Basi Revolt, which started in the hilly town of Piddig, was led by Pedro Mateo along with a few Spanish deserters from Vigan. The rebels secured the allegiance of the people along the towns they passed. However, the massive mobilization of the disenchanted folk became more unwieldy as the rebels approached Bantaoay River in San Ildefonso. The Vigan colonial forces were well positioned at the southern bank of the river that provided a natural barrier to the rebels. Despite this obstacle, the rebels tried to cross the river, but in this vulnerable position, they were easily routed. The revolt is also known as the Ambaristo Revolt, in honor of the bravest right-hand man of Mateo (Ramirez 1991, 68-74).

Folk accounts of the early 19th-century revolts must have been current when Father Jose Burgos was a young boy in Vigan, and it was perhaps inevitable that he would become a leader of the widespread clerical nationalism or secularization movement of the clergy at the close of the 19th century. When the revolutionary movement led by the Katipunan spread outside the Tagalog region, many Ilocano joined the armed struggle for independence, some emerging as top officials of the Revolutionary Government, such as Director of War Antonio Luna. Katipunero (Katipunan members) such as Isabelo Abaya of Candon and Eleuteria Florentino-Reyes of Vigan organized the townsfolk to continue the fight for independence during the Philippine-American War even long after the surrender of many generals close to General Emilio Aguinaldo (Scott 1986, 23-27). Aguinaldo sought sanctuary in the Ilocos hinterlands prior to his crossing the Cordillera on his way to his last stand in Palanan, precisely because the Ilocano defenders were fighting on many guerrilla fronts—from the Cordillera hinterlands like the Amburayan and Abra Valleys to the southernmost tip of Ilocos Norte.

Throughout the centuries of Spanish rule and even after, the Ilocano were noted for their tendency to migrate. Most of the old towns in the Ilocos spilled over to adjoining sites because of population growth and the limited areas for tillage and habitation. Beginning in mid-18th century, there was a steady migration from the coast to the midlands that was matched by a movement of settlers from the uplands to certain uninhabited coastal sites, particularly in the northern reaches of the Ilocos. Many folk accounts in Ilocos Norte towns trace the original settlers of these towns to Tinguian clans from the uplands who first came down to trade but subsequently founded farming and fishing villages.

Toward the end of the 18th century, the scarcity of land and population pressure impelled more Ilocano families to set up homesteads in the Cagayan Valley, at the opposite side of the Cordillera, as well as in melting pot areas like Tarlac, Zambales, and Pangasinan. The friars also conscripted entire Ilocano families to join the pioneer settlements in the country’s southern regions, including Mindanao and Palawan.

|

| General Manuel Tinio (Colorized by the Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines) |

Most of northern Luzon, including the Ilocos region, was already in the hands of the Filipino revolutionary army at the time of the signing of the Treaty of Paris, which turned over the country to the young imperial nation, the United States. Filipino resistance within and around Manila delayed the entry of the American forces into the Ilocos. In November 1899, the Ilocos forces, headed by the 23-year-old General Manuel Tinio of Nueva Ecija, were pitted against the American army and navy. Tinio and his generals, the Villamor brothers Blas and Juan of Abra and Estanislao Reyes of Vigan, resorted to guerrilla warfare. Military vicar general Father Gregorio Aglipay mounted a separate campaign in Ilocos Norte. The Americans starved out the guerrillas by destroying crop sources and preventing local support by hamletting and stockading towns and barrios. Ilocano resistance ended in April 1901 (Scott 1986, ix-xii).

When the plantations in Hawaii and the west coast of the United States called for contract workers in the first decade of the 20th century, most of the adventurous cane cutters and fruit pickers who responded were Ilocano peasants. Some 200 Ilocano sugar plantation workers arrived in Hawaii in 1906 and 1907. By 1929, Ilocano immigrants to Hawaii had reached 71,594. Most of the 175,000 Filipinos who went to Hawaii between 1906 and 1935 were single Ilocano men (Foronda 1976, 25; Pertierra 1994, 58).

|

| Major Isabelo Abaya, center with cane, and his Igorot recruits during the Philippine-American War, Candon, Ilocos Sur, 1899 (Photo courtesy of Arnaldo Dumindin) |

The laborers who worked in Alaskan canneries were also Ilocano migrants. The struggle of the Ilocano in the United States to fulfill their dreams was chronicled in the novel America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan, an Ilocano migrant from Pangasinan, who saw the exploitative system of that period as something more harsh and uncertain than the conditions in the Ilocos farms. Quite a few of those Ilocano migrant workers secured a college education in the United States and came back to the Philippines to teach. Some persistent ones stayed on long enough to earn a pension, which they sent to their relatives in the Ilocos or used to buy a house and some land in their Ilocos hometown. Many of the new concrete houses rising in recent times amid farms in the Ilocos, from Pangasinan to the tip of Ilocos Norte, have been built by these repatriate Ilocano adventurers or their heirs.

The hidden coves and valleys of the region became the guerrilla zone when the Japanese invaders landed on the Ilocos coast in December 1941. Following the strategy of political control set up by the American colonizers, the Japanese Imperial Army persuaded some local officials to cooperate with them while they hunted the defiant leaders in their upland guerrilla bases. The lack of unity of the Ilocano guerrillas was partly due to conflicting areas of operation and partly to the rivalries of American and Filipino commanders.

The coves in Santiago, Ilocos Sur and the remote bays in Bangui, Ilocos Norte were the secret landing sites of supplies from Allied forces. The guerrillas, however, could not operate extensively because of the cramped coastal terrain and population density. Hence, there were relatively light wartime clashes and destruction during the Japanese occupation. Besides, the Ilocos was then under the care of the Society of the Divine Word whose key missionaries were Germans. There was a concerted effort among these missionaries to impose discipline on the Japanese soldiers who respected the priests because Germany and Japan belonged to the Axis powers.

The Ilocano were divided in loyalty during the Japanese occupation, as they were under the American regime. Some leaders swayed the people into accepting Japanese control, in the same way Mena Crisologo of Vigan and Claro Caluya of Piddig had persuaded the people to show allegiance to the American flag earlier in the century. Pro-Japanese leaders went around the region campaigning in public gatherings for the Japanese-sponsored Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. At the same time, some leaders went to the hills to organize guerrilla forces, such as Floro Crisologo of Ilocos Sur and Roque Ablan of Ilocos Norte. However, the guerrilla groups were not united and this prevented them from inflicting severe damage to the invading forces. Worse, their disunity sometimes gave rise to fake guerrilla leaders or units who harassed the people more than they fought the Kempeitai forces. The Ilocano guerrillas became more active when the Japanese Imperial Army retreated to the Cordillera upon the return of the American forces. They displayed their gallantry side by side with the Americans in the capture of Bessang Pass in Cervantes, where the Japanese concentrated their forces to enable General Tomoyuki Yamashita to regroup his command staff on the other side of the Cordillera. After the battle, many Ilocano were awarded various medals and citations, a few of which later turned out to be dubious because they are not found in the records of the United States Armed Forces in the Far East (USAFFE).

|

| General Artemio Ricarte (Colorized by the Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines) |

Right after the defeat of the Japanese Imperial Army, the social and political situation in the Ilocos was not stable because of the lingering effects of the clash of loyalty and the rifts in the community caused by the war, as well as the treasonous acts of certain leaders. The postwar general amnesty program cleared the courts of numerous charges and countercharges arising from the wartime killings and reprisals.

|

| General Antonio Luna (Colorized by the Official Gazette of the Republic of the Philippines) |

The Ilocano conscripts to the USAFFE, like other Filipino soldiers throughout the country, were deprived of most of their wartime benefits because of the Rescission Act passed by the US Congress in 1946. In 1991, the US Congress approved the USAFFE veterans’ application for American citizenship, but the recent law does not provide for the restoration of financial and other benefits legally extended at the height of World War II.

The Ilocos region is the stronghold of the Marcos dynasty. Despite the ouster of the dictator Marcos Sr. in 1986, his wife Imelda and two children, Marcos Jr. and Imee Marcos, have won national and provincial electoral seats (Associated Press 2010). Thus, the Marcos dynasty exemplifies a basis for the description of the Ilocos region as the “solid north.” This epithet, however, is belied by principled Ilocano individuals who have put up a persistent resistance to Marcos’s martial law and its lingering effects at the price of either their freedom or their lives. Jose Maria Sison, born in 1939 in Cabugao, Ilocos Sur, founded the left-wing youth organization, Kabataang Makabayan (KM) in 1964, revived the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) in 1968, and organized the New People’s Army in 1969. Having gone into hiding when martial law was declared in 1972, he was captured in 1977, tortured, and kept largely in solitary confinement until his release in 1986, when the newly elected president Corazon Aquino declared amnesty for all political prisoners (Toledo 2012).

Antero Guerrero Santos, 1948-1971, of Laoag, Ilocos Norte, was a student leader in the years leading to the First Quarter Storm of 1970. By 1971, he had taken his political convictions to the remote mountain villages of Isabela, where he was learning to organize farmers and to expand the resistance movement against the Marcos dictatorship that had just begun. Santos, along with three fellow activists, disappeared in the currents of a river in Barrio Dipogo, Isabela, as they were fleeing heavily armed government soldiers. To this day they remain desaparecido (Bantayog 2015).

Poet and visual artist Alan Jazmines, born in 1944 in Ilocos Norte, was arrested in 1974 and 1982, both during martial law. In 1978, his torture in the hands of the military, as well as that of his fellow political detainees, drew major international attention to the brutality of the Marcos dictatorship. He remains in political detention since his arrest for the third time in 2011, despite the Philippine government’s guarantee of immunity for him as a consultant on the peace talks between the government and the National Democratic Front (“Alan” 2015).

Events that led to the 2000 EDSA Revolt, which ousted President Joseph Estrada and ended in his conviction for plunder in 2007, were triggered by anomalies in Ilocos Sur’s Virginia tobacco industry. In 1992 Republic Act (RA) 7171, also known as “An Act to Promote the Development of the Farmers Producing in the Virginia Tobacco-Producing Provinces,” was passed primarily through the efforts of then Ilocos Sur Rep Luis “Chavit” Singson. It provided for a “tobacco excise tax fund,” which meant that 15% of the tobacco tax collected by the national government should be returned to the four tobacco-producing regions: Abra, Ilocos Norte, Ilocos Sur, and La Union. In 1999, Singson, who had been governor of Ilocos Sur since 1992, publicly accused Estrada of receiving 130 million pesos in kickbacks out of the 200 million of Ilocos Sur’s tobacco excise tax fund (Rufo 2013; Associated Press 2000; Sandiganbayan 2007).

Ilocanos' Way of Life

The harsh climatic intervals in the region are not conducive to the lush tropical verdure found in many parts of the country. When the southwest monsoon blows in, the northern reaches of the Ilocos experience the country’s highest average rainfall. Then from mid-November to March, the coast is visited by the Siberian winds, locally known as amian, bringing the lowest average rainfall in the archipelago. The deforestation of the range since the Spanish times has caused massive erosion and siltation of riverways.

|

| A tobacco farmer in Sulvec, Narvacan, Ilocos Sur, 2017 (Freddie G. Lazaro) |

Largely because of the extreme weather changes and the scarcity of arable land, the Ilocano have evolved an intensive system of agriculture and social values to cope with seasonal adversities: adaptability, frugality, industry, and neighborliness. To make ends meet, even marginal farm lots are tilled almost all year round to suitable crops. Rice, corn, and various vegetables are the main crops for subsistence in the region. Cotton, camote or sweet potato, tomatoes, garlic, and onions are grown either after the harvest of the staples or after the rains, both for the table and the markets. The town of Sinait, Ilocos Sur, is the garlic-trading center, which continues to thrive despite the country’s growing dependence on imported garlic. Besides providing garlic to retail markets, Sinait has the capacity to deliver a regular supply of several metric tons of peeled and powdered garlic to at least one popular fast-food chain nationwide as well as a food and cosmetic company (Guiang 2013).

In every town, certain farms are still devoted to sugarcane, although it is no longer the main cash crop since the introduction of Virginia tobacco in the 1950s. Sugarcane is processed into hard brown-sugar cakes, the favorite native wine basi, and vinegar. Coconuts are raised in shoreline sitios for the oil, which has varied uses among the Ilocano, from massage liniment to expectorant, as well as for the meat used in making bibingka (rice-flour cakes), kalamay (rice-flour-and-coconut sweets), and bocayo (candy from grated coconut). Mango orchards now enjoy a boom in Pangasinan.

Extinct farm products are cotton, indigo, and maguey. Indigo dye was a major export commodity shipped to Europe and the Americas up to the turn of the 20th century. Maguey used to be grown more extensively for making ropes, bags, and sandals. Native tobacco, brown and sun dried, has always been grown largely for home consumption and the local market.

Carabaos and cows are raised by the Ilocano for a dual purpose: first as a draft animal for the farm and for transport; and second, for meat. There are not as many goats as hogs and chickens in the Ilocano farm and yard. Deer meat is a delicacy available during the hunting season in the wilds of Abra and Ilocos Norte. Abra is the breeding place for horses used for the calesa (horse-drawn carriage) in Vigan and its environs, and the bigger karetela designed for transporting harvests from the farms around Narvacan, Ilocos Sur and Bangued, Abra.

Most craftware of the Ilocano is made primarily for use in their livelihoods: saddle and bridle from Bangued; bamboo and twine baskets from the upland towns; clayware from San Nicolas, Ilocos Norte; burnay stoneware jars from Vigan; salakot or dried gourd hat from Abra; stone mortar and pestle from San Esteban, Ilocos Sur; abel or handloom fabric from Bangar, La Union, Caoayan, Ilocos Sur, and Paoay, Ilocos Norte; shell craft from various towns of La Union; slippers and sandals from Vigan; bolo and scythes from Santa, Ilocos Sur; wooden furniture from San Vicente, Vigan and Bantay, Ilocos Sur; and bamboo baskets and furniture from various places in Pangasinan. Being utilitarian in intent, these craftware are generally made to last and are rarely ornate or decorated.

|

| Burnay makers in Vigan, Ilocos Sur, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

The exceptions to this pragmatic aspect in skilled artistry are jewelry making, now a vanishing art, in Bantay, Ilocos Sur; the carving of religious icons; and furniture making in San Vicente, also in Ilocos Sur. Vigan’s famous guitar and violin craft is almost a thing of the past while harp making in Bacarra declined after the transistor radio began to blare in farmers’ huts all over the region.

Other cottage industries that thrive because of necessity and not on account of entrepreneurial acumen are salt making, bagoong (fermented salted fish) making, seaweed gathering and processing, meat processing for longganiza and chicharon, making of delicacies and sweets for pasalubong, and preservation of fish, including the highly valued fry called ipon harvested in certain months along mouths of big rivers. Aquatic food items caught or raised in inland waters and fishponds form a sizeable portion of the Ilocano viand. But fishing is a relatively marginal activity in the Ilocos mainly because of inadequate gears and lack of entrepreneurs to pioneer offshore trawl fishing.

Large-scale mining in the region has caused ecological destruction, dislocation of local residents, and loss of people’s livelihood. Black sand, also known as magnetite iron ore, is dug out of the shores of Aparri, Buguey, and Lallo in Cagayan for export to China. As with other industries generating enormous profits, black-sand mining has been embroiled in a graft-and-corruption case amounting to 10.7 million pesos against a government head and, in another case, caused the homicide of a mayor of Cagayan (GMA Network 2013; Whymining 2014; ATM 2015; Bernal 2014; de Guzman 2014; GMA Network 2014.).

Ilocano outmigration has had a long history since the Spanish colonial period. The Ilocano have pioneered in lowland farming techniques in other regions and been employed as government bureaucrats, military personnel, and teachers. A significant amount of the provincial revenue comes from overseas workers whose remittances have almost entirely supported some barangays (Torres- Mejia 2000).

The colonial vista of Vigan, arising from the rows of brick-and-tile ancestral houses hugging the narrow streets, has made it a favorite place for location shooting among filmmakers, either from Filipino film studios or foreign outfits. In the mid-1950s, Hollywood filmed The Day of the Trumpet starring John Agar, in Vigan. Many period movies made by Fernando Poe Jr. were filmed here. These ventures have given some part-time jobs to Ilocano talents, artisans, hoteliers, and food vendors.

Ilocos Norte’s Bangui and Pagudpud wind farmsare icons of 21st century technology, being electric power generators utilizing wind as the energy source. Blending with the province’s scenic landscape, the turbines are tourist attractions, standing in a row along several kilometers of the shoreline and facing the West Philippine Sea. The Bangui Wind Farm, established in 2005, is the first in Southeast Asia. Its 21 wind turbines generate 52 megawatts (MW) of electricity, while those of Pagudpud generate 81 MW. Since 2013, the 50 turbines of Burgos Wind Farm in Ilocos Norte, being larger than those in Bangui, have been drawing even more tourists (Lazaro 2015).

That the ouster of President Joseph Estrada in 2000 was caused by anomalies in the tobacco industry of Ilocos is a stark illustration of the inextricable intertwining of politics and economics in the region. It began in 1956, when the Ilocano president Ramon Magsaysay legislated support for the industry and its farmers. During its 16-year existence—from 1956 to 1972—the Farmers’ Cooperative Marketing Association (FACOMA) earned the epithet “pakumaw,” referring to a horseback-riding, black-garbed bandit and kidnapper, but which was the farmers’ word for “letting your tobacco disappear.” This was because local political bureaucrats and landlords had taken control of the FACOMA and were cashing in on its benefits, which had been meant exclusively for the farmers (Torres-Mejia 2000, 35).

In the 1960s, the tobacco monopoly in Ilocos Sur was in the hands of the Crisologo family, the father being a congressman; the mother, the provincial governor; and their son, heading a private army called the saka-saka (barefoot). Farmers were forced to sell to this family at 1/5 the price that their tobacco leaves could have fetched in the neighboring province. The other three provinces did not fare significantly better: Out of a reported 35 million kilograms tobacco leaves harvested in this whole region, the actual export of tobacco leaves was a mere 1 million kilograms. Banana and papaya leaves were substituted for tobacco, and receipts were issued for “ghost merchandise.” The anti-heroes to these villains in the system were the unlicensed buyers called “cowboys” who bought the tobacco leaves on the field at risk of their lives. Haggling was their method of transaction, thus allowing the farmers some power over the price (Torres-Mejia 2000).

In 1970, the industry collapsed, but so did the ruling dynasty: The congressman was assassinated in the Vigan Cathedral; his wife was defeated in the elections by a cousin who would play a pivotal role in the impeachment of future president Estrada in 2000; and their son was sentenced to life imprisonment for the burning of two barangays in Bantay municipality. In 1972, the government shifted to the principle of laissez faire and opened up the tobacco industry to free trade: Transnational corporations were allowed entry, and rural banks offering tobacco loans replaced the FACOMA (Torres-Mejia 2000).

In 1999 to 2007, the total amount of the tobacco excise fund for the four tobacco-producing provinces added up to 10.057 billion pesos, intended to be used exclusively in the interests of the tobacco farmers. Ilocos Sur was to receive 50%, the largest share of the fund, and the rest was to be divided among the provinces of Ilocos Norte, La Union, and Abra. In 1999, the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) reported to the justice department that Governor Singson had taken 170 million pesos in cash advances from the fund. The anomalies continued after Estrada’s conviction in 2007. In 2009, the Commission on Audit (COA) reported that 1.3 billion pesos of the same fund had not been properly liquidated by the office of the governor. Moreover, it was used to finance expenses disallowed by RA 7171 such as the non-functioning 332-million-peso tomato paste plant in the town of Santa, the privately-owned Multi-Line Food Processing International Inc, a badminton court, a thousand T-shirts, contractual workers’ wages, and office supplies. In 2013, Ombudsman Conchita Carpio-Morales filed graft charges against Singson and his successor Deogracias Victor Savellano for having misspent at least 26 million pesos of the fund (Rufo 2013; Rappler 2013).

Ilocos Political System

Unlike in Cebu or Manila, there were no distinguished chieftains in the region when the conquistadores raided the coastal villages. The political system was rooted in the clan or the extended family structure. This made it easier for the colonizers to establish their encomiendas and political dominance. The clan system also enabled the emergence of leaders and warlords who directed the people in the series of revolts that wracked the region.

|

| Ilocos Norte Capitol, 2014 (Alaric A. Yanos, Provincial Government of Ilocos Norte) |

As in Mexico, the Spaniards established the pueblos as the first step in colonizing the Ilocos. The church and other ecclesiastical buildings were in the center of the pueblo, as were the politico-military offices and quarters. The plaza and surrounding streets were used for religious rituals and military drills. These streets strung the houses of officials and the principalia who owned most of the landholdings. As in other pueblos, the town planning was compelled by the dual objectives of conquest and conversion.

In the Ilocos, as in other regions of Christianized Philippines, the friars enjoyed tremendous powers. Under the patronage of the Spanish king, the members of the clergy were exempt from civil governance, nor could they be transferred by the governor-general without the king’s approval. Thus, the friars combined the powers of the church and royal protection. But in the Ilocos, ever an active base for colonizing the uplands and a region far from the central government, the friars assumed extra powers and privileges over the flock and the guardia civil (constabulary). For one, they were often more up-to-date on public and private affairs than the local officials. Moreover, elections to political office and undertaking of public projects required friar approval, which effectively diminished local leadership (Scott 1986, 10-11).

The political structure was the same for all the pueblos. The principalia elected from among themselves the gobernadorcillo, the municipal mayor who was dependent on the support of the cabezas de barangay who, in turn, were responsible for collecting taxes and extracting labor services from the citizens. The provincial governor or alcalde mayor was most of the time a ceremonial figure, acting more as an overseer for projects originating in Manila. The self-perpetuating principalia carried out civil governance under the guidance of the friars. Because these native rulers were the power brokers of the clans, it was also from their ranks, ironically, that rebel leaders or warlords emerged time and again.

These leaders enjoyed ready support from among their tenants and workers, as well as their extended families composed of blood and affinal relations among other families of the landed gentry. Moreover, they enjoyed the loyalty of the people who were traditionally in awe of the maingel (brave and just), the way their highland neighbors and kin followed the minger or mingel, the brave ones. In 1818, the Spanish colonial administration divided the Ilocos province into Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur to distribute the rapidly growing population and to keep a tighter control over the people (Wallace 2006, 16).

Under the American colonial administration, most of these clan leaders in Ilocos who led the people’s fight for freedom were eventually harnessed by the new colonizers in the pacification campaign as well as in the mass-education program. The same method was used by the Japanese invaders, but a number of American-educated professionals joined the guerrilla forces in the hills.

Officially, the Ilocos region is governed by the Department of Interior and Local Government, acting in behalf of the president. The provinces are each headed by a governor and a vice governor, with a representative for each district, and board districts composed of four members each. The municipality is a conglomeration of a number of barangays and is administered by elective and appointive officials. The barangay is synonymous to a village, consisting of not less than 1,000 inhabitants and administered by a set of elective officials headed by a punong barangay. The barangay functions as a basic arm for delivering goods and services at the community level. The purok is the smallest unit, a number of which compose the barangay. The purok leader and his or her council settle neighborhood disruptions, such as noisy family squabbles, stray animals, drunken behavior, and petty theft. The gravity of the problems, ranging from social issues to hard crime, determines whether these should be elevated to the barangay, municipal, or provincial authorities (Wallace 2006, 17-18).

In 1987, the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) was created out of five provinces in the Ilocos Region and Cagayan Valley. In a 1991 referendum and then again in 1999, Abra, together with all but one of the Cordillera provinces, voted against the autonomy of the region, which would have been called the Cordillera Autonomous Region (Casambre 2006).

The political rivalries today, which become volatile during election periods, are still driven by customary leadership based on clan loyalty and on vested interest, centering on the control of the government resources and the yearly tobacco trade. The rise of the Ilocano bloc in Congress from the 1950s to the 1960s was propelled by the tobacco subsidy, which was part of the business strategy of deported American tycoon Harry Stonehill. From this corporate base, using the big earnings from the tobacco trade, Stonehill succeeded in manipulating Philippine politics and industry with the help of Ilocano politicians. When Stonehill was ousted from power in the mid-1960s after the investigations of Jose Diokno, then top state prosecutor, the profitable tobacco trade became a source of rivalry among Ilocano politicians.

The gunslaying of the powerful congressman Floro Crisologo inside the Vigan Cathedral is believed by many Ilocano to have been linked with the rivalry for the control of the tobacco industry, the major cash crop of Ilocos and the prime factor behind the rise and fall of many Ilocano politicians. Studies on the links of the tobacco industry and Ilocos politics have shown that trade in this cash crop has provided the financial resources and overzealous supporters during poll campaigns, thus making it the most emotional issue among Ilocano voters.

This livelihood in the Ilocos became the power lever of some Ilocano leaders who created the myth of the “solid north”—which led to widespread terrorism and electoral fraud. Through the “solid north” scheme, politicians from other regions desirous of the “solid” Ilocano vote were pressured to support the tobacco subsidy and the power play of the Ilocano leaders. Grateful tobacco traders were the main source of money and materials for this type of politicking.

For good or ill, the Philippines has had three Ilocano presidents: Elpidio Quirino, Ramon Magsaysay, and Ferdinand Marcos. Other prominent Ilocano leaders are Quintin Paredes, Camilo Osias, Vicente Singson Encarnacion, Benito Soliven, Ignacio Villamor, Jorge Bocobo, Josefa Llanes-Escoda, Salvador P. Lopez, Onofre D. Corpuz, Fred Ruiz Castro, and Jose Maria Sison. In 2008, Grace Pádaca, a two-term governor of Isabela from 2004 to 2010, received the Ramon Magsaysay Award for Government Service. Coming from a middle-class family with parents as educators, she had achieved the improbable feat of breaking the power of the clan dynasty that had ruled the province of Isabela since 1967. Her political base was composed largely of her listeners, to whom she was “Bombo Grace,” broadcaster and political analyst on Bombo Radyo in Cauayan, Isabela, from 1986 to 2000 (Sipress 2004, A28; RMAF 2008).

Ilocano Culture, Traditions and Customs

The precolonial social structure in most parts of the archipelago consisted of three layers within each community (de Loarca 1705 and 1903; de Plasencia 1906). In the Ilocos, the top layer was composed of the babaknang families, who later comprised the principalia; the cailianes, who owned home lots but tilled the landholdings of the babaknang clans; and, at the bottom, the adipen or slaves, who became such by birth or for indebtedness.

|

| Ilocano farmer wearing native hat, cape, and rain skirt and Ilocana vendor wearing saya, tapis, and baro (Laplace 1835) |

Among the cailianes usually emerged the artisans and specialists like the healers, salt makers, stem cutters, and wood gatherers, who supported themselves by their labor. They also provided labor to the babaknang when the season called for it, as in monsoon months when the farms required more hands, or when the well-to-do needed some house repairs and extra help during banquets and social gatherings. The cailianes normally brought some produce from the farms and orchards for the banquet and brought home a token of food served at the party. This customary practice of give-and-take has strengthened the bonds between these groups—the upper class providing the occasion and bounty to be shared, the lower class giving their labor and loyalty. Some social scientists prefer to focus on the behavioral and attitudinal aspects by calling it patron-client relationship, where the rich and the powerful serve as the constant source of social and psychological aid when the poorer families are in dire need. Generally, however, there has been a considerable degree of social mobility among the cailianes, particularly because they have special skills and therefore can migrate or form new homesteads far from the community.

The agkakabbalay (household) begins with a newly married couple living in their own house, not with their parents. The couple calls each other asawa. When they become parents, their anak (children) call the father tatang and the mother inang. Siblings are kabsat: The older brother is manong and the older sister manang; the younger sibling, regardless of gender, is ading. Other kabagyan (relatives) compose their own households in their own residences. The ikit are the siblings and their spouses on the father’s side; the uliteg are the siblings and their spouses on the mother’s side. Male cousins are called kasinsin; female cousins are kapiddua. One’s nephews and nieces are kaanakan. The brother-in-law is kayong, the sister-in-law, ipag; their spouses are abirat. The manugang are one’s son- or daughter-in-law. The katugangan are the parents-in-law. Members of a nuclear family that might typify the migrant tendencies of the Ilocano may be dispersed geographically thus: one son in Hawaii, two sons in Cagayan and Mindanao; the youngest son remaining behind to tend to their small landholding; one married daughter living in her husband’s residence; and one unmarried daughter staying home to look after the parents (Wallace 2006, 26-27; Griffiths 1988, 16).

The system of public education and the diverse prospects in professional life have eroded the social barriers of old. Moreover, the migration of Ilocano workers has further blurred this social levelling. Today, the traditional feasts and holidays still revive the social divide between the rich and the poor, or between the old rich and new rich, simply because the trappings of wealth in the past—like lifesized religious statuary and residence in premier blocks of the town—always come to the fore during these social and religious rituals. Hence, although retired balikbayan (returned overseas workers) may have acquired assets and a financial capacity equal to those of the old rich, they do not have the social and political connections, having been away for most of their adult lives and having risen from humble, often peasant origins (Griffiths 1988, 56-57; Torres-Mejia 2006, 32).

An occasion for either establishing or affirming one’s social prestige, besides being an occasion for community revelry, is the town fiesta. It may be held on any of the following special days: the feast day of the town’s patron saint, the anniversary of a historic event, or at the peak of the town’s trading season. The selection of the fiesta queen, which highlights the celebration, is also the climax of a month-long series of fund-raising activities. The votes for the candidates are purchased by friends, relatives, and political or institutional sponsors such as the parish church or a school. The candidate who brings in the most money is proclaimed queen. Final canvassing is done on fiesta night, interspersed with fund-raising dancing and food auctions. Men choose their dancing partners from among the candidates for a fixed amount. Traditionally, the price is “five pesos a dance.” The candidates’ supporters auction off food items, ranging from chocolate boxes to lechon (roasted pig). A government official who is also the town patron is expected not only to outbid supporters of his own candidate but also those of all the candidates. A chocolate box, for instance, has been known to cost an official 17,500 pesos. The funds collected go to fiesta expenses and a community project such as a waiting shed or an artesian well (Wallace 2006, 203-207; Griffiths 1988, 61-63).

Growing up the Ilocano way is to imbibe steadily the customary beliefs and rites, alongside the current trends in culture purveyed by mass media. The cherished beliefs and practices of previous generations can still be observed in some villages far from urban centers, or in families where wisdom and sentiments of the elders hold sway.

A family can call upon any of five folk healers when a member falls ill or needs medical assistance: The mangagas, also known as arbolaryo, is the traditional healer who has a thorough knowledge of the medicinal properties of a wide range of herbs, including the leaves, roots, bark, flowers, and seeds. They treat not only physical illnesses but also those caused by invisible beings. The partera or mangablon (unlicensed midwife or birth attendant) primarily helps the mother deliver her baby but on other occasions, may also be consulted on gynecological matters. The mammullo treats bone injuries and other related aches and pains with massage techniques and various kinds of massage oils. The mannuma treats animal and insect bites, which can range from the venomous to the tiny. The mannuma uses a small piece of glass or carabao horn to cut the affected skin, so he can suck out the poison (Wallace 2006, 34).

Some beliefs relating to prenatal care and child rearing are still observed, though they are waning. These include discouraging the woman from eating dark-skinned fruits lest the child is born dark; and discouraging her from sitting at the top of the stairs so that their labor pains will not be prolonged. Sitting on a mat or rug minimizes the pain of childbirth. Sleeping at daytime will cause her baby to have ebbal (edema), bloated face and feet. A woman who does not tie her long hair back whenever she goes out will cause her to deliver a snake with her baby. She takes some salt with her to keep evil spirits from snatching her unborn child. There are taboos as well for friends and relatives of the mother-to-be. Anyone standing on the threshold of her home will cause her a difficult delivery. When the woman is in labor, visitors must be kept away lest any one of them might be carrying a sungat, which brings bad luck. As soon as his wife’s labor starts, the husband conducts the anglem, which is a simple ritual of burning a pile of old rags in a bak-ka (clay jar) underneath the house to keep evil spirits away. He also jumps over his wife three times for good fortune (Wallace 2006, 27).

To ensure that the child will be intelligent, the placenta and a pencil are wrapped together in a newspaper and buried; additionally, a folded newspaper is placed under the infant’s head as a pillow. The umbilical cord is dried and kept by the mother among her personal jewelry to ensure that the child does not abandon its parents when it has grown. If the newborn wears used clothes, it will grow up to be frugal. However, these must be carefully chosen because the baby will become close to the owner of these clothes (Wallace 2006, 30).

During the dalagan (first 15 days after delivery), the mother continues to heed certain prescribed actions and taboos to ensure her recovery. She lies on a balitang (inclined bamboo bed) with her child to make her bleeding flow down. Every day, she takes a drink of herbal tea purchased from the Yapayao, a neighboring ethnic group, and inhales the sidor (medicinal incense and smoke from a bowl of hot coal). The day after her delivery, she bathes in water with guava and pomelo leaves. On the fifth day, in a process called sarab, she is wrapped in a mat with heated guava leaves so as to warm her womb. Sitting on banana leaves wrapped around hot wood ashes has the same effect. On the ninth day, she takes a bath in water that has been filtered through rice-straw ashes. On the 15th day or when the hilot, partera, or mangablon decides that she can resume her normal routine, the mother takes the tennab, a bath lasting long enough for her to soak in alternating hot and cold water (Wallace 2006, 29-30).

A number of taboos and prescribed behavior attend the newborn child as well. Before the infant’s first foray from the home, a sign of the cross is drawn in charcoal on the baby’s face, and garlic is pinned to its clothes to fend off malignant beings. Keeping the baby’s first gift of money will give it a lifetime’s virtue of thrift. The baby sleeping on its stomach will bring financial misfortune on the family. A haircut before the baby’s first birthday will shorten its life. An adult touches the baby’s forehead when it enters his or her house for the first time so that it will feel comfortable. If a mother takes her baby along on a visit to someone else’s house, she deliberately addresses it by name and tells it to come along before they leave so that its soul does not stay behind (Wallace 2006, 30).

The onset of a girl’s puberty is marked by her first menstruation. She must then heed taboos and prescriptions during her menstrual period. Sitting on the third to the last bottom step of the ladder or stairs leading to the house will ensure that the period will last no longer than three days. Eating sour food causes the blood to clot, which in turn causes menstrual cramps. Taking a bath or washing her hair will stop the menstrual flow. On the other hand, puberty for boys is marked by the ritual of kugit (circumcision), which is done when he turns 13 (Wallace 2006, 31).

During courtship, when the suitor is shy or the woman’s parents are tight lipped, old men are relied upon to provide the discreet motions and verbal performance designed to ensure more positive responses. The “rooster courtship” exemplifies this indirect approach. Here, a suitor provides an old man a rooster to bring to the girl’s father. The old man brings the rooster to the girl’s house and tells the girl’s father that he would like the rooster to crow in their yard. The father asks whether the rooster, meaning the suitor, is “domestic,” meaning from the same barrio, or “wild,” meaning from outside the barrio. The old man identifies the rooster and soon after, divulges the suitor’s name. If the father seems open to the suitor, the old man gives him the rooster.

Today, courtship unfolds in schools, parties, parks, and the movie houses, since most areas are markedly urbanized. Moreover, public education and mass media have also made inroads into the folk beliefs and practices in the Ilocos. However, in traditional courtship, women are told to be careful and not to give any of their personal effects to a suitor. Since it is believed that personal items bear the owner’s karma or spirit, this taboo would prevent the suitor from gaining full control over the girl’s feeling and soul. To be sure, such a custom or its variations elsewhere in the region is resorted to by suitors from tradition-bound families.

When the man and woman have agreed to marry, the man conducts the panagpudno, in which he calls on his future parents-in-law to ask for their consent. The palalian is a subsequent meeting that includes the suitor’s relatives and his panglakayen (spokesman), who negotiates with the parents on the sab-ong (bride price), the sagut (the cost of the bridal trousseau), and the parawad (the suitor’s token gift to his prospective mother-in-law). The sab-ong is in the form of cash or property, such as a piece of land or a farm animal. It is presented the day before the wedding in a grand ceremony called albasya. During their engagement period, the couple avoids traveling because their betrothed status makes them particularly vulnerable to mishaps. Agsaksi, also known as getting their marriage license at the municipal hall, is done by the engaged couple in the company of their parents. The wedding can either be a church or a civil ceremony (Wallace 2006, 25).

Weddings are the most exuberant of occasions because they either expand or intensify the clan links. It is in nuptial feasts where traditions are most pronounced. After the wedding, the newlyweds return to the house, where an elderly woman with a gift for oratory conducts the lualo, which is a prayer for blessings on the couple. The couple then greets their ninang (wedding sponsors) by touching the back of each ninang’s hand to their forehead. With plate in hand, the newlyweds collect gifts of cash from their guests (Wallace 2006, 26).

After the meal, the bitor is held. Here family relations and pride come to the fore, and rich kinsfolk outdo one another in giving topak gifts (cash or farm lots) to the newlyweds. After a relative has given a gift, he or she drinks a glass of basi, which has been placed on a stand at the center of the dancing area. To induce their relatives into giving more, the couple dances continuously, waltzing close to each relative who is then cajoled by the rest to give a gift. Since this contest of gift-giving aims to help the newlyweds make a good start in life, tradition impels the relatives to give whatever they can.

In a similar vein, family reunions during wakes and burials are occasions for tears, laughter, and feasting. Feasting is mostly on meat, a reflection of the underlying cultural belief in sharing meat and blood to reinforce kinship. The festive atmosphere of reunions may be interspersed with sudden tears upon the arrival of relatives.

Another custom shared with the Cordillera inhabitants is the long wake to enable distant kin to bid their last goodbye to the departed. Those coming from distant places might reveal that a black butterfly had suddenly flown into their living room, a sign that the dead indeed conveyed his/her departure. After the burial, the bereaved family goes into the river or seashore to wash away their grief and the languor from the sleepless nights, when playing cards and mahjong tiles competed with the wailers who expressed the agonies of the clan and the goodness of the departed through the chanting of the dung-aw (dirge).

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Ilocano People

The Ilocano share much of the indigenous belief system prevailing throughout the archipelago that underlies what has been called folk Catholicism, a blend of precolonial and colonial precepts.

The Ilocano believe in the beneficial and harmful influences of creatures of the netherworld. To the Ilocano, Namarsua is the supreme spirit who created both the world of nature and the spirit realm. Mount Mawakwakar is the abode of all the spirits. A favored person may be flown to this mountaintop in a sailboat and taught how to heal people with the medicinal plants growing here (Griffiths 1988, 78).

The al-alia is the spirit of the dead, which appears as a hazy pale figure. The pugot is the denizen of groves and giant trees that may be harmful if provoked; when friendly, it can be the source of a taguilinged charm, which gives the possessor the power to make oneself invisible. Mangyaoaoan is the spirit hovering in woodlands and streams that play pranks on trespassers. The manggagamud (witch) is the scourge in the Ilocano’s daily life because it could be a neighbor, a relative, or a coworker.

To counteract the spell of a mannamay (witch), one keeps a bottled potion of roots and oil on the wall of their home or paints blood-red crosses on their doors. An anib (amulet) of special roots, salt, and garlic, or a piece of ginger and a knife keep spirits away. A shield against lightning is an anib of roots purchased from the neighboring Yapayao ethnic group and blessed by a priest on Palm Sunday (Wallace 2006).

The supernatural power to punish an offender is believed to belong mainly to women. And it is also the women who are usually consulted about omens and dreams, and the best time to plant, hunt, go to war, and marry.

Ilocano cosmology links the here and now with the afterworld, hence the belief in hovering ghosts during wakes or in naluganan (possessed), whereby the spirit of the dead enters the body of a living person to communicate with certain relatives. Shady towering trees are regarded with awe, since these may be inhabited by the supernaturals generically called kibbaan or ansisit. If one must cut such a tree, one shouts “Dayo, dayo,” or “cayo cayo,” a contraction of umadayo kayo, meaning “go away.” Anthills and similar mounds along the road should not be touched lest the kibbaan are provoked to cause harm. Passing a lush corner of a yard or close to a large tree is preceded by an invocation: “Bari bari,” meaning “please let me pass.” Nausea or a general weakness may be a state of an-annong caused by having nakadalapos (bumped or disturbed) the kibbaan lurking around the bushes.

To relieve the person of this malaise, an older relative plucks a twig from a tree such as malunggay and gently brushes it on the victim’s head and body while muttering to the unseen kibbaan to let go. If the victim’s condition persists, the relatives offer atang, a ritual food offering to appease the supernaturals. The mangangatang or manglolualo (prayer leader) places the atang on a winnowing tray and takes it to the dwelling of the offended kibbaan who is implored to accept the offering and to restore the person’s health. The atang consists of a mixture of grated coconut and oil, surrounded by bits of crushed coconut husks and shells (Picache 2012; Gagelonia 1967, 470-471).

|

| Women in Paoay, Ilocos Norte honoring the dead with atang, 2013 (Grazielle Mae A. Sales, Provincial Government of Ilocos Norte) |

The complexity of the composition and performance of the rites of propitiation increases for as long as the patient remains sick. A more elaborate rite centered on blood offering is a white pig: One-half of it is left at the site where the afflicted had a brush with unseen spirits; the other half is taken home to the sick person. The third type of atang is more difficult because the mangangatang must ask the community members for the ritual items without explanation and without anyone else touching these items. However, if this rite proves just as ineffectual, the most elaborate atang must now be addressed to the most powerful kibbaan. A chicken is sacrificed on a small makeshift altar in the patient’s yard. Its meat is the centerpiece of the atang, which “includes rice cakes, a glass of water, three pieces of dinubla (rolled tobacco leaves), oil from a coconut with reddish-brown husk, betel-nut chew, and fruit” (Gagelonia 1967, 470-471; Picache 2012).

Since the Ilocano traditional universe links the natural and the supernatural realms, rites of appeasement and thanksgiving are done periodically for the spirits dwelling in the loam, river, and woodland. This traditional worldview, which has persisted in a modified and more casual manner, may incorporate traces of ecclesiastical rites. Religious syncretism, which merges indigenous and Christian rites, was observed during the Diego Silang revolt in 1762. As the rebels entered each town, they were welcomed with “anito sacrifices,” which are indigenous rituals and offerings, much to the friars’ dismay. After a victorious battle, Silang’s brother-in-law, Benito Estrada (Gabriela’s brother), reenacted the Eucharistic sacrifice by drinking wine over the decapitated heads of the Spanish colonialist troops. The rebels wore both a white cross and an anting-anting (talisman) composed of the following items: “some [strands of] hair, threeroots, a fruit called ‘cat’s eye,’ a piece of ginger, some wax stuck to a piece of paper, some leaves, and a dry areca leaf” (Palanco 2002, 528-529).

The merging of indigenous and Christian tenets continues today. For instance, upon opening a bottle of liquor, the host usually first sprinkles a few drops of liquor on the ground, like a priest sprinkling holy water. The intent is to offer the kadkadua (unseen partners) their share of the repast and merriment. The religious feasts such as town fiestas honoring the patron saints and other Christian holidays are occasions for communal piety or revelry. An elaborate blending of the customary and contemporary beliefs and rituals may be seen in the defunctorum, in which the priest leaves the church premises and goes to the orchards, farms, and springs to pray to the in-dwelling spirits to keep on helping the tillers produce food from their domain. After the invocation, the farmer offers the priest a token of the harvest.A fusion of olden and current rituals is the setting up of the abong-abong (shed for a temporary altar) along the route of the procession during the Holy Week. The bamboo-and-thatch shelter is decorated with a variety of native fruits and flowers. This abong-abong rite has an affinity to certain rituals of chanting and harvest offering among the upland dwellers. The lectio (chanting of the pasyon) echoes the traditional dung-aw dirge normally heard during wakes and burials. To the devout, Semana Santa is a very intense period of prayers and processions; to the less pious, it means a series of gawking sessions on the roadside as the procession passes by and sharing liquor and food with friends and relatives.

Indigenous religious beliefs and practices are predominant in rituals for wakes and funerals. These are presided over by an elderly widow whose status has earned her the right to communicate with the spirit world. Several kinds of atang for the spirit of the deceased as well as other spirits lurking nearby are prepared for the umras, rituals marking various stages of mourning. These are held on the afternoon after the burial, on the 30th day after the burial, and a few days before the first death anniversary (Picache 2012).

As soon as a person dies, the widow slits a chicken’s throat outside the house to determine if the spirit of the deceased has accepted its fate: If the chicken flies up, the spirit is willing to go on to the next world; if the chicken falls to the ground, the spirit wants to stay on. The family builds an atong (a bonfire of neatly piled firewood) in the front yard and keeps it alive until the funeral. This is to announce to passersby that there is a death in the family (Picache 2012; Wallace 2006, 32).

The first and simplest atang is cooked over this bonfire on the first night of the wake. This consists of a bunch of half-ripe saba (a type of banana) and a rooster, if the deceased is male, or a chicken, if the deceased is female. The aroma of this atang cooking over the bonfire is meant for the pleasure of the spirits (Picache 2012). During the nine-day wake, candles are kept burning constantly to keep evil spirits away. Mourners wear a barabad (white headband). Until the burial, the dead is treated as if still alive: The usual meals and beddings are prepared to avoid giving them offense (Wallace 2006, 32; Madamba 1984, 20).

The second atang is held in the early hours of the day of the funeral. The mourners wear black if the deceased is an adult, and white if a child. The internal organs and best parts of a butchered pig are strung on a stick, one end of which is stuck to a beam inside the house. The rest of the pig is either buried or served to the men who have helped prepare the pig. The officiating widow deliberately breaks a small pot and makes another chicken sacrifice. When the coffin is lifted to carry it out, it is first turned around twice clockwise and then once counterclockwise. Care is taken as the coffin is being moved so that it does not touch any part of the house, or else another death will follow shortly. All openings of the house are tightly shut to keep malignant spirits out. When the funeral procession begins, a headless rooster is left in the path of the procession for the benefit of the dead relatives so that they can prepare for the newcomer in the afterlife. The funeral rites are led by the minister to whichever religious denomination the family belongs (Picache 2012; Wallace 2006, 32).

After the burial, the bereaved family does the diram-os, the washing of their faces and arms with basi from a basin into which coins have been placed to drive away the kibbaan. Upon their return home, the family opens all the doors and windows, which are kept open for the next three days in readiness for the visit of the soul of the deceased on the third day (Wallace 2006).

The first umras is held before sunset on the afternoon after the burial, in time for the coming of the spirits, for whom the most elaborate atang is prepared. On the bed of the deceased, a kilo of rice grains is placed in the form of a solid cross, on which five eggs are placed, following the outline of the cross. Near the head of this cross is a lighted candle. Twelve platefuls of native delicacies are placed equidistantly around the cross-shaped rice grains, thus covering the surface of the bed (Picache 2012).

The food offerings consist of a variety of glutinous-rice cakes: Patupat is unsweetened, slightly salted rice cake contained in a triangular pouch of woven strips of a banana or palm leaf and boiled in sugarcane juice and coconut milk. Linapet is a cylindrical cake, with the glutinous rice, coconut milk, and molasses mixed together before it is boiled, wrapped in a pre-cut piece of banana leaf, and steamed. Busi is puffed rice mixed with molasses and shaped into a fist-sized ball. Kaskaron is boiled bel-laay (rice flour) mixed with coconut, shaped into a ball, and then coated with sugar. Baduya is made of deep-fried flat halves of saba mixed with rice flour. Binuelo is grated coconut mixed with sugar and sesame seeds. Pilais is fried ground rice. Linga is made of sesame seeds mixed with molasses and shaped into diamonds. Ninyogan is glutinous rice mixed with coconut milk and egg. Several of these pieces of glutinous-rice concoctions are carefully piled on each of the 12 plates in six layers and fenced around by pieces of linapet standing to form a pyramid. Complementing these are pieces of fried chicken, a glass of basi and of water, bits of tobacco, bua (betel nut), and gawed (betel leaf) (Picache 2012).

The following day, the bereaved family buries the ingredients of the betel chew at the riverbank and throws a sack of the ashes gathered from the atong into the river. They stand on the riverbank, facing east, as the widow performs the gulgul (ritual washing of their hair) on each one, using a mixture of river water, basi, and the ashes of rice stalks. The widow leads them into the river until their heads are completely under water, and she helps each make two turns counterclockwise, and one clockwise. As they emerge out of the water, they leap over a pile of burning rice stalks onto the riverbank. Upon their return home, another widow dabs coconut oil on their hair, forehead, and nape three times, washes their face with a basinful of water mixed with basi, and gives their forehead three gentle taps (Picache 2012).

In the next nine nights, the mourners hold a prayer vigil consisting of a lualo for the dead and the rosary. The second umras, with another atang, is held on the ninth night (Wallace 2006, 32-33; Picache 2012).

The official mourning period lasts a year, during which pamisa (feasts) are held periodically to honor the deceased: the makasiyam on the ninth day after the death; makabulan, a month after; and pitobulan, seven months after. A few days before the makatawen, or the first death anniversary, the family performs the gulgul again but this time facing west, to express their acceptance and letting go of the loved one. The waksi, or the end of the mourning period, is marked by the family shedding their black mourning clothes and holding the grandest atang and feast. Ingas or ladawan (idols) of wood, stone, ivory, or gold may be carved in memory of the dead (Wallace 2006, 32; Picache 2012; Madamba 1984, 20).

|

| Gregorio Aglipay, Obispo Maximo of the Philippine Independent Church (Foreman 1899) |

Besides Roman Catholicism, which is the predominant religion among the Ilocano, there are six other religions in the Ilocos region: Iglesia Filipina Independiente (IFI, founded by Ilocano priest Gregorio Aglipay), Iglesia ni Kristo, Saksi ni Jehova (Jehovah’s Witnesses), Seventh Day Adventists, Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and Pentecostal Protestants. In 1961, the IFI and the US Episcopalian Church became sister churches (Wallace 2006, 35).

During the Marcos regime, religious institutions of various denominations and their members in the region served their God by serving and protecting their fellow Ilocano in defiance of martial law. In 1974, Catholic schools in the whole province of Abra suspended classes for the funeral of peasant organizer, farmer, and school principal Santiago B. Arce, who had been tortured and killed in a military camp. The people formed the longest funeral procession in the province’s history despite fear of reprisal from the military. Jeremias Aquino, a priest of the IFI, also known as Aglipay Church, spoke out against martial law and the Cordillera dam project in his homilies. He was arrested in Sadanga, Mountain Province in 1979, released in 1980, and killed in a road accident in 1982. Father Zacarias Agatep of Ilocos Sur was a Catholic parish priest of Caoayan. He was an outspoken critic of the ruling class’ exploitation of tobacco farmers. Arrested in 1980, he was released in time for the visit of Pope John Paul II and was killed by the military in 1982. In 1980 he had written: “If it is a crime to love the poor and support them in their struggle against injustice, then I am ready to face the firing squad.” Filomena Asuncion, a deaconess of the United Methodist Church of Isabela province, spoke on behalf of the oppressed peasant class in her homilies and helped to organize farmers’ cooperatives. In June 1983, she was captured by government forces, tortured, and killed (Bantayog 2015).

The Ilocano Community

The major precolonial settlements in Ilocos like Sual in Pangasinan, Balaoan in La Union, Narvacan and Vigan in Ilocos Sur, and Laoag and Paoay in Ilocos Norte were situated along the coast or near the mouths of rivers, which made for easy traffic of trade goods between the coasts and the hinterlands, and foreign merchant boats as well. Thus, Balaoan was quickly renamed Puerta de Japon by the Spaniards who saw Japanese boats unloading merchandise there. Sual, which is the Arab word for port, most likely refers to the wharf for traders retailing goods from Malacca and the southern provinces of China where the Silk Road trade had its network of bazaars. This old commercial link brought beads, ceramic jars, and plates to Ilocos that were sold to the mountain dwellers.

|

| Abra Provincial Capitol, 2014 (Romel Rafor Jaime) |

The Spaniards transformed these tradeposts into pueblos and garrisons with a central plaza, using the Mexican pueblo complex as their model. They connected these settlements by means of the camino real or the royal highway where the king’s soldiers and missionaries must pass from one town to the next when delivering royal decrees or quelling dissidents. However, the sea continued to be the principal passage connecting coastal towns, islands, and nations.

Dominating every town was the iglesia or simbahan (church). The massiveness of churches and their central location beside the main plaza were due to their dual function in the life of the colonial pueblo. Apart from serving as houses of worship, they doubled as fortified shelters for the townspeople in times of Moro slave raids, invasion, and rebellion. The towering facades of churches face the sea because the highest windows and the niches served as lookouts for approaching vessels or invaders. Many bell towers were built separately and completed later when there was enough money for the big bells from Belgium or Mexico.