Tinguian (Itneg) Tribe of the Philippines: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People |Ethnic Group]

“Tinguian,” "Tinggian", “Tinggianes,” “Tingues,” and “Tingians” all mean “mountain dwellers” and refer to the people who, to avoid the advancing Christian Ilocano, withdrew into the Abra valley and the nearby highlands. “Tinguian” is used synonymously with the word “Itneg,” derived from iti uneg, which literally means “the interior,” or from the combination of the prefix i-, which indicates a place of origin, and Tineg, the name of a major river and geographical area (Schmitz 1971, 20). The Tinguian have always thought of themselves and the other highland dwellers of the Cordillera as Itneg, people of the interior uplands. Non-Itneg, however, tend to refer to the inhabitants of Abra’s isolated hinterlands as Itneg and to the province’s more acculturated population as Tinguian, especially since the latter are supposedly hardly distinguishable from the lowland Ilocano.

Today, there are two identifiable Tinguian groups, namely, the valley Tinguian and the mountain Tinguian. The first occupy the village communities where there are also Ilocano settlers, particularly the municipalities of San Quintin, Langiden, Danglas, Lagayan, San Juan, Lagangilang, Peñarrubia, Villaviciosa, and Manabo. The second are distributed in sparsely populated areas in the highland country of northern and eastern Abra. The ancestral domain of the Tinguian covers a mountainous region, which has four valleys and four river systems joining up with Abra River, which empties into the West Philippine Sea. Tinguian territory is bounded on the north by Ilocos Norte, on the west by Ilocos Sur, on the south by Bangued, and on the east by Kalinga and Apayao. The Tinguian are found mainly in the towns of Tubo, San Quintin, Luba, and Boliney in Abra.

Tinguian or Itneg also refers to the language spoken within the province of Abra and to a lesser extent, in nearby Kalinga and Apayao. There are nine varieties of this language, spoken in 25 out of the 27 municipalities of Abra: Inlaud, 9,000 speakers, spoken in Bucay, Danglas, Dolores, Lagayan, Lapaz, Langiden, Lagangilang, Peñarrubia, Pilar, San Isidro, San Juan, San Quintin, Tayum, Villaviciosa, and Luba; Adasen or Adasseng, 5,720, spoken in Lagayan, Lagangilang, and Tineg; Maeng, 18,000, spoken in Tubo, Villaviciosa, and Lacub; Masadiit, 7,500, spoken in Boliney, Bucloc, and Sallapadan; Banao, 3,500, spoken in Malibcong and Daguioman; Mabaka, undetermined number of speakers, spoken in Lacub and Malibcong; Binongan, 7,500, spoken in Licuan-Baay, also known as Baay-Licuan; Gobang or Gubbang, undetermined number of speakers, spoken in Malibcong; and Moyadan or Uyyadan, 12,000, spoken in Malabo. The Tinguian elders themselves would add Aplay and Balato or Balatok to the list to make 11 in all. Inlaud, being the language in 15 of the 22 municipalities, is the most widely dispersed. The total number of speakers of the seven out of 11 languages surveyed is 67,620.

In 1904, the American census reported a combined population of 27,648 Tinguian in the provinces of Ilocos Sur and Abra. In 1988, they numbered around 57,000. As of 2000, the Tinguian population in these same two provinces is 51,089, broken down as follows: in Abra, 45,739 or 22% of the province’s total population of 209,146, which is predominantly Ilocano; in Ilocos Sur, 5,350 or 0.9% of the province’s total population of 594,206.

Video: NUEVA ERA Ilocos Norte - Live the TINGGUIAN way! Culture and Natural Beauty [TRAVEL Philippines]

History of the Tinguian (Itneg) Tribe

One theory has it that the Tinguian originally inhabited the coastal areas and are the predecessors of the precolonial Ilocano. These people would later move into what is now the province of Abra, where they intermarried with the older population. The descendants of this union are the present-day Tinguian. Others, however, went further upland toward the east, northeast, south, and southeast, following the many branches of the Abra River. The group that trekked to the northeast along the river called Tineg encountered Aeta who inhabited the region called Apayao. Those who intermarried with these Aeta came to be called Isneg, an ethnolinguistic group that now populates the western and northern parts of the present Kalinga-Apayao. The pure Aeta group may be found in the Apayao region.

|

| Tinguian woman (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Older and more recent studies have shown that a close affinity exists between the Itneg and the Ilocano, and whatever difference exists as a result of acculturation, mainly through Christianization, has remained superficial. Both groups share commonalities of language, cultural traits, and physical characteristics. There seem to be only very slight differences between the lowland Tinguian, the mountain Tinguian, the Ilocano, and the Apayao.

|

| Tinguian man (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Spanish colonization of the Ilocano started in Vigan in 1572, but it was not till 1598 that the Spaniards initiated contact with the Tinguian when they invaded Abra and used the village of Bangued as their garrison. This drove the Tinguian farther up the river, where they founded the Lagangilang settlement. Hence, attempts to convert the Tinguian were largely unsuccessful. In Abra, the Augustinian missionaries forayed from Bangued into the mountains to resettle them in the lowlands under the colonization process called reduccion but could only report failure by 1738. In Ilocos Sur, where conversion of the Ilocano had gone more swiftly, only 156 Tinguian were resettled between 1702 and 1704. In the mid-18th to 19th century, 1750s to 1850s, resettlement of the Tinguian progressed slowly, compared to the Ilocano population. In 1760, the villages of Santiago, Magsingal, and Batac in Ilocos Sur were established for 454 Tinguian. In Abra, at least 1,000 Tinguian were resettled near Bangued, Abra, in 1753 and, by the 1850s, there were five more Tinguian settlements.

Voluntary assimilation, rewarded by tax exemption and other benefits, failed to attract the Tinguian. Forced to live in pueblos, they were burdened with taxes and forced labor. There is some evidence that Gabriela de Estrada, wife of Diego Silang who led the Ilocos revolt of December 1763, was a Tinguian mestiza born in Barangay Endaya, Vigan City. Gabriela’s brother, Benito Estrada, was among Silang’s followers who practiced anito worship and head taking. They celebrated their victory over the Spanish troops with ceremonial wine drinking over the enemies’ heads. When Spanish reinforcements arrived in Vigan in August of the same year, the widowed Gabriela Estrada escaped to the mountains of Abra with the other rebels. The Spaniards lost 35 soldiers in a battle at Sitio Banaoang, where presumably Gabriela had Tinguian support. However, on 20 September, the rebels were defeated by Spanish reenforcements that came by sea from Cagayan. Gabriela and 90 others were hanged from the gallows that were built on the site of battle.

In 1868, Capt Esteban de Peñarrubia, newly appointed military governor of Abra province, banished the nonconverts from their homes and confiscated their property. Their own traditional garments were banned in the towns. Christianization increased through intimidation because the practice of old customs was made punishable by law. Mounting hostility and the exploitation of the Tinguian alienated them further from Christian Filipinos. Nevertheless, trade relations continued and with the support of the Spaniards and later the Americans, the Ilocano influence grew.

Tinguian warriors armed with traditional weapons joined the Philippine Revolution of 1898 against the Spaniards and then the resistance war against the Americans. Under American rule, head taking practically disappeared after it was outlawed and head takers were arrested and imprisoned. A gold mine was established by the Americans just before World War II in Baay but was shut down permanently when the war broke out.

In 1973, shortly after President Ferdinand Marcos declared martial law, a pulp-and-paper company, the Cellophil Resources Corporation (CRC), owned by Marcos crony Herminio Disini, was granted a Timber and Pulpwood License Agreement (TPLA) to cut down 198,795 hectares of centuries-old pine tree forests spread over Kalinga-Apayao and Abra (Supreme Court 2010). This would either destroy or despoil the Tinguian’s rice fields, irrigation systems, river and forest resources, water, fertile soil, and their homes. Legitimate attempts by the local leaders and the people to lodge their protests were met with intense militarization, which, during the martial law years, was synonymous with human rights atrocities. Four Catholic parish priests in Abra—Conrado Balweg, Nilo Valerio, and the two brothers Bruno and Cirilo Ortega—vainly attempted to mediate between the two parties. Finally, village chiefs and leaders of Abra came together in Mayabo, Abra for a bodong (peace pact) with other Cordilleran groups, who collectively signed a pagta (agreement) to persist in their struggle to stop the CRC.

In 1979, construction of the pulpmill was completed and so began its operation. In the same year, Balweg joined the communist New People’s Army (NPA) in unity with his people’s efforts to protect and defend their ancestral domain. So did Valerio and the two Ortega brothers. In August 1982, an NPA attack on the CRC camp in Lamunan, Abra resulted in three logging trucks and a bulldozer destroyed, and radio, chainsaws, and other logging equipment confiscated. In December 1983, in another NPA attack, 3.2 million pesos worth of logging equipment was destroyed (Bagadion 1991; Manalang 1992; UCA News 1986).

In 1984, simultaneous with the escalation of nationwide protests against the Marcos regime, the CRC pulp mill stopped its operations. It still stands abandoned today. In March 1986, a month after Corazon Aquino’s victory over Marcos in a snap election, Balweg and the Ortega brothers broke away from the NPA and formed the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army (CPLA). A year before, their fourth fellow ex-priest, Valerio, had been ambushed and killed by the Philippine Constabulary (PC), Integrated National Police (INP), and a paramilitary group, the Civilian Home Defense Forces (CHDF). On 13 September 1986, the three CPLA founders, together with Tinguian elders, met with President Aquino in Mountain Province to forge a sipat (cessation of hostilities) so that negotiations for the autonomy of the Cordillera region would proceed. The first step in the process was Aquino’s Executive Order No. 22, which created the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) in 1987. However, the Cordillera Autonomous Region had yet to come to fruition when Balweg was assassinated on 31 December 1999 in his hometown of Malibcong.

On 4 July 2011, a “closure agreement” between the government under Benigno Aquino III’s presidency and the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army (CPLA) provided for the disarmament of the CPLA and its conversion into a nongovernment organization (NGO) to implement a socioeconomic development plan that would benefit the 57 villages that had been the CPLA’s mass base. This decision, however, was protested by the Kalinga members of the CPLA, including Balweg’s own son Jordan, claiming that this move had made impossible the fulfillment of the 1986 sipat for Cordillera autonomy. However, on 29 December 2012, for compelling reasons, Jordan Balweg and 57 other CPLA members were integrated into the Philippine Army, as provided by the closure agreement.

Abra has won certain gains for itself. The yearly celebration of Cordillera Day on April 24 is also the Tinguian people’s recollection of their victorious “anti-Cellophil struggle” and their equally successful resistance of Marcos’s Binongan River dam project. The geopolitical unit that is known today as the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) used to be composed of the provinces of Benguet, Ifugao, Bontoc, and Kalinga-Apayao, leaving out Abra to become part of the Ilocos region. The inclusion of the Tinguian homeland in the Cordillera region is a late recognition of the fact that the Tinguian have a very clear cultural affinity with the Igorot groups, even though a significant part of their society has also been closely identified with Christianized Ilocano society.

Livelihood of the Tinguian People

The Tinguian practice dry and wet agriculture in the highlands and the lowlands, respectively. Rainwater is conducted to terraced fields by means of ditches. Dams are constructed to divert the flow of streams by means of ditches and flumes. In the lower and wider terraces, the carabao-drawn plow is used, this implement having been introduced during the Spanish period. The main crops are rice, corn, sweet potato, and tubers. Sugarcane is also planted, its juice used in the preparation of basi, a favored beverage in the north. Among the domestic animals are dogs, pigs, chickens, and carabao. In recent times, horses and cattle have been introduced.

|

| Bamboo split weavers in Abra (Bern Traveler) |

The rich waters of Abra River and its tributaries have made fishing an important source of sustenance and livelihood. Fishing is done with kitang (earthworms) as bait as well as more elaborate means and tools. Shrimps and mudfish are caught with the bobo (bamboo fishing tool). The asar is a flat bamboo floor enclosed by two tarik (bamboo fences) forming a “V,” which effectively catches fish during the flood season. Aguyan is communal fishing: a line of people drives schools of fish toward sack traps secured by another group of people upstream. Fish collected in the morning are shared by all during lunch, and those caught in the afternoon are equally distributed to all participants.

Aside from agriculture and fishing, the making of iron tools is an important activity. The Tinguian produce many kinds of blades and weapons, including kitchen knives, bolo, and gaman (headaxes). It appears that the Tinguian had no knowledge of mining iron ore. They secured the iron slugs from coastal areas even as far back as pre-Hispanic times when they used to buy these from the Chinese who brought iron bars. The smith’s forge consists of two upright cylinders made of wood.

Tinguian weavers produce blankets, which are known for their use of traditional and symbolic representations, as well as new designs. Men manufacture ropes, baskets, nets, and many kinds of traps. Women make mats and do pottery. The articles produced in these industries have furnished the people the things they need, but over a long period of time, the Tinguian have also engaged in trade with the outside, especially the lowland and coastal regions of the Ilocos. The selling of timber, bamboo, and rattan has provided them with cash income. Trade is made convenient by the fact that these articles can be floated down Abra River to the markets.

Abra’s industries are mainly agriculture, fishing, and logging; thus, property and land ownership is the primary source of economic and political influence. Most work in the agricultural system; the rest are wage earners in privately owned establishments and government service. Education is not a common means of social mobility, as only about a quarter of the population graduate from high school and only around 4% acquire a college degree.

Tinguian socioeconomic life retained much of its traditional character up to the 1950s and the early 1960s. However, changes in the economic mainstream started to impinge on Tinguian society since then. The liberal importation of textiles into the country increased, hence displacing locally woven cloths. Tinguian weavers were not exempted from these developments. In recent years, there has been a constant decline in the supply of indigenous woven material from which the highly touted burial blankets of the Tinguian, and their apparel, are made. In the past, the Tinguian were producing their own cotton, and they used traditional material in perpetuating old designs or creating new ones. This was primarily because every phase of their life cycle required a certain type of cloth to be worn or displayed in the many rituals, feasts, and celebrations held periodically.

The agricultural life of the Tinguian suffered with the introduction of Virginia tobacco in the 1960s. Farmers focused on cultivating this cash crop rather than maintaining self-sufficiency in rice and other staple crops. The cash crop did little to improve the economic situation of the Tinguian. Prices of tobacco were manipulated, and the Tinguian farmers were cheated by intermediaries in the purchase of tobacco leaves.

In 1992, Republic Act (RA) 7171 or “An Act to Promote the Development of the Farmers in the Virginia Tobacco-Producing Provinces” provided for a 15% share of the national government’s locally grown Virginia tobacco tax collection, also known as tobacco excise tax, for the four tobacco-producing regions in northern Luzon: Abra, Ilocos Sur, Ilocos Norte, and La Union. Out of this 15% tax collection, Abra receives five percent, which corresponds with the amount of tobacco it produces relative to the other three provinces.

RA 7171 allows funds from the tobacco excise share to be used by tobacco farmers to help toward their self-reliance through cooperatives, alternative farming systems, agro-industrial projects, and infrastructure projects, particularly farm-to-market roads. However, as of 2013, no proper accounting has been made by the province’s local government in its use of its excise tax share. In 2013, the three million that was meant for financial aid to any of the province’s 43 registered tobacco farmers’ organizations was given to various types of groups instead. Disbursements worth 17.2 million pesos have no record of beneficiaries. Purchases of construction materials worth two million pesos, besides farm equipment and materials such as water pumps, fertilizer, tractors and sprayers, have no record of the recipients nor the purpose for these. All in all, no proper accounting could be made of the use to which the province’s excise tax share was being put because no separate bank account had been opened for it, as mandated by RA 7171.

The Tinguian group has become one of the most marginalized groups in the Cordillera. Economic underdevelopment, the inaccessibility of their mountainous homeland, and attempts of the Marcos regime to exploit their vast timberlands for large-scale logging and processing of forest products for corporate profit contributed to the growth of insurgency throughout Abra. Thus, Jovencio Balweg, who joined the NPA like older brother Conrado, remained in it until his capture in 2009. The town of Lacub, which was the stronghold of the anti-Marcos and anti-Cellophil movement, continues the struggle, this time to protect its 14 mine sites, where local and small-scale miners may soon be dislodged by large mining companies encroaching into its territory.

The Tinguian Village System

All villagers customarily recognized a lakay or elderly patriarchal figure, the wisest and most perceptive person in the community. He was assisted by other male elders of the village who were also considered wise and intelligent and could be depended upon to deliberate on matters concerning the welfare of the village. They constituted a kind of council of lallakay (the elders) under the leadership of the lakay. This council upheld kalintegan (justice) and deliberated and decided on issues regarding social behavior such as divorce, theft, and retaliation. However, the Tinguian did not accord absolute authority to the lallakay, because the patang or sapu (opinion) of the people was of equal importance in determining right and wrong. The Tinguian village did not develop a system of wards or political subunits analogous to the Bontok ili, the simplest form of town organization in northern Luzon. The lakay system, however, has served as an effective way of integrating Tinguian society.

|

| Tinguian man (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Head taking was an established practice among the Tinguian, even among fellow Tinguian, though they refrained from doing it with their immediate neighbors. Those who lived two or three villages away, of a distance of 16 to 24 kilometers, were in danger of being attacked. There were two reasons for this practice: first, the taboos of burial and mourning could not be lifted until this requisite was fulfilled, and second, it was a measure of a man’s great achievement to be a head taker. When he returned to his village after a successful headhunt, he was welcomed with a celebration of dancing, singing, and feasting, with neighboring villages participating. The warriors’ weapons were the spear, which he let fly when his prey was about three to seven meters away, and his shield and headaxe for cutting off the head of the felled prey. The upper edge of the warrior’s shield was carved in the shape of a “W”; the three prongs that this created were used to catch the warrior’s human prey by the legs and hold them fast, while the two-pronged bottom was used to secure the neck before he cut it with a downward stroke of his headaxe. The prey or enemy could also be slowed down with soga, tiny bamboo spikes planted into the ground and hidden in the grass.

With the assimilation of this cultural community into the national-local centralized political system in the Philippines, the role of the village council, where it still exists, may no longer have the full authority and influence it used to wield over the life of the community. But the wisdom of the old is still very much respected and their counsel taken to heart by a new generation of Tinguian who give value to the customs and traditions handed down to them.

Tinguian / Itneg Culture, Customs and Traditions

The basic unit of the Tinguian social village organization is the family, in which kinship ties have remained strong, although no kinship terms are used. Social status is measured by wealth, particularly the ownership of heirloom treasures such as ancient Chinese pottery, porcelain, copper gongs, as well as possession of work animals and rice fields. A family that has a substantial collection of such forms of material wealth is regarded as belonging to the baknang (affluent). Wealth is hereditary; thus, the traditionally rich and poor could be expected to pass on their social status to succeeding generations. Nevertheless, social mobility is possible through hard work and thrift. Of a higher class than the baknang is the dulimaman, whose members have supernatural powers. Additionally, as in many indigenous societies across the country, traditional Tinguian society had alimban, women who were kept isolated from the rest of the community until they were married. The dulimaman and alimban are the principal characters of the Tinguian epics.

|

| Tinguian wedding ceremony (The Tinguian: Social, Religious, and Economic Life of a Philippine Tribe by Fay-Cooper Cole. Field Museum of Natural History, 1922.) |

Elaborate religious ceremonies attend childbirth, although the act of delivering the baby itself is a very simple and swift procedure. When the time of delivery comes, the expectant mother kneels or squats on the floor while clutching a rope or bamboo pole that hangs from a house beam above her. A midwife attends to her and, when the baby is delivered, cuts the umbilical cord with a bamboo knife. Bamboo leaves, which signify healthy growth, are placed in a jar, which will contain the placenta. An elderly relative takes the jar to a spot that signifies what occupation is desired for the child: if a hunter, the jar is taken to the forest; if a fisherman, it is taken to the river. However, it is never buried, because this will make the child grow to be a fearful person. Meanwhile, the father constructs a baitken, a square, bamboo frame that he places beside the mother. In it ashes are contained and a fire is lit for the mother’s warmth and protection against evil spirits.

A naming ceremony follows after the infant has been washed. An elderly man or woman lays the infant on a winnowing tray turned back side up, lifts the winnower slightly up and down while pronouncing the infant’s name, and enjoins it to be obedient to its parents, with such injunctions as “When your mother sends you, you go” or “When your father sends you to plow, you go.” The infant is given at least two names, one each belonging to an ancestor on the parents’ side.

It is after childbirth that the mother must now obey rules for prescribed behavior and taboos. On the day of her delivery, she is helped to wash in water that has been boiled with herbs and leaves that evil spirits abhor. During the first month after her delivery, she bathes a prescribed number of times each day and follows a prescribed number of cold or hot baths. During the same period, a piece of ayabong tree bark is placed underneath the house and is kept burning to ward off evil spirits. Above the infant’s head are hung a miniature bow and arrow and a bamboo shield to which a leaf is attached.

The baby sits astride its mother’s hip or is slung on her back with a blanket. A crying baby might be soothed with a tobacco pipe that the mother transfers from her mouth to the baby’s. At the age of two, the child undergoes the olog ceremony to prevent it from crying and to keep it in good health.

For toys and games, the boys’ favorite is the wooden top. These are spun with great skill, the aim being to hit one another’s top hard enough to split it or at least leave a mark on it. The girls have miniature pestles with which they play, pounding rice grains. The wooden snake toy that moves almost realistically is made from a slender bamboo pole that is cut at uniform lengths crosswise and fastened with rattan strips or thread. A group game for boys and girls is the maysansani, which is similar to hide-and-seek. Each player lays four fingers on the palm of one player, who tries to capture the fingers after counting, “Maysansani, duan-nani, mataltal, ocop!” (One, two, three, ready!). The child whose fingers are captured becomes the “it” and must find everyone who has run away to hide.

A tradition called tani, no longer practiced today, was the betrothal of children between six and eight years old. This was done by parental arrangement. The first step in the process is the danun or kalkalimusta, when the future groom and his parents, accompanied by the village panglakayen (head elder), call on the future bride and her parents. A series of ritual negotiations takes place, with the panglakayen speaking as the intermediary for the boy’s family. The priceless manding (agate beads) and the less valuable uldot and manggila beads are offered by the boy’s family as ba-ag (tokens) of affection to the future bride. The panglakayen recounts the boy’s desirable traits and his family background to convince the girl’s family of the advantages of marrying the prospective groom. Upon the acceptance of the proposal by the girl’s family, sillot, also called beddel or batek (beads), are attached to her wrist to signify her betrothal.

The date for the pakalon, or the fixing of the sab-ong (bride-price), is set. This might consist of livestock, jars, blankets, and other valuable items. Over time, these items have been replaced by any or all of the following: money, a house and lot, a farm lot, and a carabao. These are very important considerations for the bride’s family because these guarantee a secure life for her. The pakalon having been agreed upon, a feast is held for the relatives of the couple at the girl’s house. On the day set for the pakalon, pigs are slaughtered and favorable omens read before the bride price is finally settled. Finally, the groom’s family pays the girl’s parents and relatives a fraction of the pakalon as a “downpayment.” If the girl comes from another village, the boy’s parents may need to make gift offerings for every stream that the girl and her parents must cross, in addition to the pakalon agreed upon. The close of the negotiations is celebrated all night with much drinking, the singing of either the daleng or salidummay, and the dancing of either the tadek or lab-labbaan (dance for religious occasions) on the grounds of the house. On this dancing area stand three rice mortars turned upside down and set on top of one another. A container of basi is set atop this totem pole of sorts, and beside it is placed a spear with a belt.

The actual marriage ceremony takes place years after the children’s betrothal. When the day comes, the groom, accompanied by his family and other relatives, goes at night to his betrothed’s house. He offers a part of the sab-ong to the bride’s parents. The couple sits on the floor, and the boy’s mother places a coconut half shell containing water and a wooden plate of rice between them. The boy’s mother puts two beads into the water. These two beads at the bottom of the shell represent a married couple who should never part. The couple each takes a sip of the water, which represents the need for cool heads in a marriage. They each take a fistful of rice and shape it into a very compact ball. The bride lets her ball of rice fall between the floor’s bamboo slats, and the boy tosses his up in the air. If it breaks, the ceremony is deferred. If it stays intact, the ceremony is done and everyone quietly departs to leave the couple to themselves.

The couple sleeps next to each other with a barrier between them. The next morning, they walk with the girl’s mother to the spring, where the mother washes their faces with the spring water mixed with a bit of agiwas, tobacco, and bamboo leaves. The boy cuts a sprig of dangla (Vitex negundo) and hangs it on their door to signify fertility. The doors and windows are shut, and the couple consummates the marriage. The next day, sipsipot (watching) is conducted. The boy begins his period of service to his parents-in-law by cutting the grass around their fields.

On the day that the bride moves to her new home, she sits on the floor with her legs outstretched; this determines the length of the string of agate beads that her husband should then give her. For the rest of the day, the groom gives her a string of beads in exchange for every move that she makes.

The Tinguian population now being predominantly Roman Catholic, they no longer follow the custom of the tani but are instead wed according to the westernized Catholic rites, followed by a modern wedding reception. However, although the pakalon signifies the betrothal, the term is also now the Tinguian word for “wedding.”

At present, the engagement and marriage ceremonies are a mixture of ancient and modern, Westernized custom. The man, who might, for instance, be a seafarer, makes the bumaag (marriage proposal) to the woman’s parents after a courtship. The engagement period, which ordinarily lasts a year, is for saving up and raising the animals that will be butchered for the wedding feast, typically consisting of 10 pigs, 2 cows, and 4 sacks of rice. The wedding festivities last for two nights and two days, starting on the eve of the wedding. The elders dance the tadek to the accompaniment of gongs, and the youths dance to modern music played by a disc jockey (DJ). Occasionally, the DJ gives the gong players a rest by playing a modernized, rock version of the dayang-dayang, a Sama Dilaut folk song, which both elders and youths can dance to at the same time.

The next morning, the couple holds their Catholic wedding in a church. They return to the bride’s house for the traditional rites, which are officiated by the village panglakayen. The families of the couple each have a spokesperson who chants the uggayam (advice and good wishes), delivered as a poetic joust between them. A family elder reads out the terms of the sab-ong, which is the Tinguian equivalent of the Westernized marriage contract. This is followed by a modern wedding reception, which includes cake eating and wine toasting but also by lowland folk customs such as the sab-it (pinning paper bills on the newlyweds’ garments) as the couple dances the tadek, and bitor (gift-giving by the two families). After the reception, the couple goes to the groom’s house for the patan-aw (scrutiny) by those who have been unable to attend the reception. Again, there is feasting, albeit on a smaller scale, and tadek dancing.

The bride-price and other such arrangements related to the wedding immediately start interfamily relations based on obligations that are mutually beneficial to both families of the betrothed couple. These include assistance in making a clearing, in planting and harvesting, and in food exchange—a basic necessity among subsistence people. Thus, the bride-price strengthens the family and kinship structure.

|

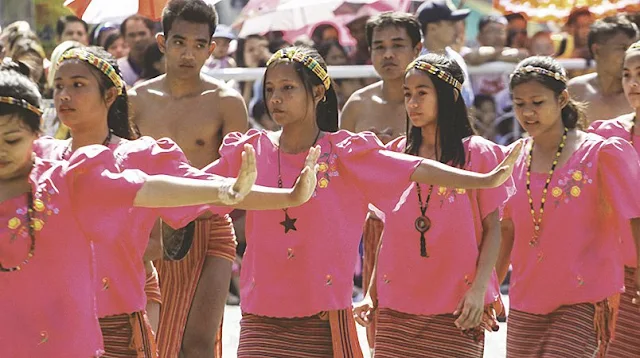

| Tinguian performing at a community gathering, 2014 (Estan Cabigas) |

The ammoyo is the custom of neighborhood cooperation to help a family build or repair their home, as well as plant and harvest crops. The family is expected to reciprocate the neighbors’ helpfulness by hosting a tagnawa feast of food and basi.

Death is the beginning of an afterlife for one who leaves this world. Several ritual practices are observed to facilitate this all-important passage from one life to the other. The corpse is washed and dressed immediately, to prepare it for its journey to the afterworld, which is called maglawa (future home). The deceased is made to sit up on the sangadel or onawa (death chair), which is made of bamboo, wearing his best clothes and beads and surrounded by his precious possessions, such as blankets, belts, and skirts or G-strings, all of which will accompany him to Maglawa. Pig and chicken offerings as well as metal weapons are used to keep away evil spirits such as Kadongayan, Ibwa, Selday, and Akop. In the yard, a container of basi on top of an upside-down rice mortar is for the benign spirit Al-lot, whose role in funeral wakes and gatherings, which involve much drinking, is to calm people down.

During the first two days of the wake, friends and relatives sing and dance in honor of the dead. Neighbors send namin (money or rice contribution) to the mourning family. The wake also involves the ritual whipping of all the guests in order to free the spirit from its mortal body, to express grief, and to share in the pain of the grieving family. Four men are appointed to lead this ritual, which is only lightly applied with a saplit (reed). The manoen chooses who shall be whipped; the agbaot performs the whipping; the agsango ensures that 400 whips are delivered, and the mangwaswas or manueldo rewards the receiver of the whipping with a cup of basi. The four men do this until all, except the old people and close relatives of the dead, receive this ritual whipping. Before the corpse is finally laid to rest, a shaman goes into a state of possession and recites the dead person’s last message to the family. The corpse is sprinkled with pig’s blood. The tadek is performed without any musical accompaniment in order to send off the kalkalading (soul) to ngato (heaven). As a final precaution, an iron plow is laid upon the grave to ward off evil spirits.

The corpse is buried under the house or within the yard, amid much lamentation in the house of the departed. This is the sang-sang-it (shedding of tears), during which the life and deeds of the deceased person are recounted in a wailing manner. In ancient times, the Tinguian practiced an elaborate ritual of river burial. The deceased was laid on a raft with provisions for the journey. Sent off with prayers, the raft was set adrift downriver, which was the direction toward the afterlife.

The morning after the burial, the widow, in the company of the other mourners, goes to the river for the golgol (cleansing). She throws in her mourning headband and then goes in herself to “wash away the sorrow” and a lakay tosses a bundle of burning arutang (rice stalks) in her direction, to “make her thoughts clear.” A more elaborate, present-day variant of the golgol is that done by the whole family. As they are bathing in the river, the bundle of arutang is distributed among them. On the riverbank, a fire is built with burnt meat and vinegar, and the bathers light their arutang with it. Each throws their burning stalk over their head as far away as possible without looking back at the rice stalks. They then go underwater and pick up a pebble each from the river bottom. They change from their old garments, which they let float downstream and take a different path home. Finally, they throw their pebbles up onto the roof of their home to keep away the spirit of the deceased.

Prescribed behavior and taboos dominate the mourning period. Relatives of the deceased suspend work and put on old clothes. The immediate family must restrict their diet to corn, they cannot touch blood, and they must walk soberly, keeping their arms at their sides. They must stay in the village and behave in a subdued manner. The widow stays in mourning for a year after the burial. Before headhunting was criminalized by the American regime, these taboos could not be lifted until the men, wearing white headbands, went headhunting and returned successfully.

The waksi (cleansing or casting away) is celebrated a year after the funeral to mark the end of mourning by festive dancing, eating, and drinking. The lay-og (final day of the waksi) is the ritual removal of the sangadel, now empty but still adorned by the personal belongings of the dead. Only then does the widow come out of her yearlong mourning period.

Relatives and friends pay tribute to the memory of the dead. The ceremony also serves to lift the sorrow of the bereaved. The celebrants partake of rice, pork, beef, carabao meat, and basi. Afterwards, an offering of rice mixed with pig’s blood is made by the shaman to the guardian stones. With the offering of diam, rice with pig’s blood, the tadek is performed. The shaman returns to the gathering with a group of men who shout to frighten away evil spirits. Near the house of the dead, a chair is laid out with offerings of food and clothing. To appease the spirits, beads, food, and clothes are laid on a shield supported by four spears. The ceremony over, the dead person’s relatives enter the house and roll up the mat used by the dead. They open doors and windows, and life goes back to normal. Along with the sang-sang-it and the golgol, the waksi survives to this day amid Christian burial and mourning rites.

Besides spirits communicating with people, various animals and their behavior or appearance can foretell good or ill fortune. The most important of these is the pig, which is used for rites of passage such as birth, childhood, marriage, and death. It is killed during religious ceremonies and its gall or liver read for omens. Warriors about to go on a headhunt examine the pig’s gall bladder, If it is bloated with bile that is bitter, they will defeat the enemy; if the opposite, they will suffer defeat. For other rituals, the pig’s liver is examined for its texture and appearance. A full and smooth liver is a good omen; a wrinkled, speckled, or lined one bodes ill. The ritual is concluded with the animal’s blood being mixed with rice and offered to the spirits.

The labeg is a small bird that the spirits send to the people when they want a bakid or sangasang ceremony to be held in their honor. When it flies into a house, the family catches it, oils its feathers, attaches beads to its feet, and sets it free with the promise that the ceremony will be held immediately. When the labeg flies from right to left in front of a party of warriors, they will be victorious; if it flies in the opposite direction, they must desist. The site for a new house should be moved elsewhere if a snake, field lizard, deer, or a wild hog appears on it. The salaksak (kingfisher) flying toward a person going on a journey is warning that person to return to where he or she has come from. A koling bird’s cry of “awit awit” (carry carry) means that a person who has gone on a journey will be carried home. A snake crawling across a person’s path into a hole is a warning that someone leaving the house will soon be buried. If a man on his way to the house of his bride-to-be is blocked by a falling tree, the couple will die. If an object breaks or falls during the wedding, the couple will meet misfortune. One good omen, however, is the sight of a flying hawk catching its prey; if so, the hunter or trader who sees it will have a bountiful day.

Evidence of bwa (betel nut) chewing as an established custom is found only in Tinguian oral tradition, since it was replaced by pipe smoking when the Spaniards introduced tabao (tobacco) into the region. The dried leaf is rolled into a thin cigar and inserted into the pipe. Everyone, from infancy, smokes, though no one consumes a whole cigar. After a few puffs, the woman sticks the pipe into her hair; the man, into his hat. The betel nut chew, however, remains an important item in spirit offerings. It is prepared in the standard way that is widespread not only in the country but all over Southeast Asia: the areca nut, which has been cut into four parts, is wrapped in a betel leaf, on which fresh lime has been spread.

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Tinguian

In Tinguian cosmogony, supernatural beings, collectively called anito, fall under three general categories: spirits who have existed through all time, spirits of inferior rank which are neither benevolent nor evil, and spirits of ancestors and other mortals who are invisible but who may enter the bodies of shamans so that they can communicate with the living.

|

| Ritual offering of pigs (Cole 1908) |

The Supreme Being is Bagatulayan, who lives and rules the celestial realm, directing its activities. Kadaklan is a deity subordinate to Bagatulayan. He is a friendly spirit who teaches the Tinguian how to pray, harvest their crops, ward off evil spirits, and overcome bad omens and cure sicknesses. In this respect, he is also known as Kaboniyan. Kadaklan’s wife is Agemem, who is the mother of their two sons, Adam and Baliyan. His dog Kimat, is the lightning, which might bite a tree or strike a field or house as a reminder to the owner to celebrate the padiam ceremony in his honor.

Kaboniyan lives in the sky but is also known to live in a cave near Patok where gongs, moving and talking jars, and the tree bearing agate beads can be found. Kaboniyan gave the human race the gifts of sugarcane and rice. He also taught the same lessons identified with Kadaklan. He has appeared to the Tinguian as a giant with a spear the size of a tree and his headaxe the size of the end of a house.

Idayaya is the deity of the daya (east) who has ten grandchildren all wearing in their hair the igam (notched feathers attached to a stick). When these feathers grow dull, these grandchildren cause someone’s illness so that they can send a message through the shaman healer that the Pala-an ceremony must be held to restore their igam’s brightness. The names of these ten grandchildren are Pensipenondosan, Logosen, Bakoden, Bing-gasan, Bakdañgan, Giligen, Idomalo, Agkabkabayo, Ebloyan, and Agtabtabokal.

Sasailo are spirits that dwell in the natural surroundings, move among human beings, and exert influence on events and activities in human society. The sasailo possess powers and intelligence which are equal or superior to those of human beings, and they become the basis for certain sanctions and prohibitions that must be followed by people, on pain of retribution. They are to be feared and respected. Taking the form of human beings, they move about, aware of everything that is going on.

There are good and evil sasailo. One good spirit who dwells in the natural surrounding is Makaboteng, meaning “one who frightens,” also known as Sanada, the guardian of the deer and the wild pigs. Sabian is the spirit-guardian of dogs. Kaiba-an is the guardian of the rice fields and is the creator of “the ground that grows,” which is the termite mound. Bisangolan, “the place of opening or tearing,” is a giant who uses his headaxe and staff to keep the river from overflowing. Kakalonan, also known as Boboyonan, is a most congenial spirit who tells the people the cause of their problems and the solutions to these. Al-lot calms people down at gatherings. At a wake for the deceased, an offering of basi for him is placed on top of a rice mortar turned upside down in the yard. Bayon is the spirit of the fresh breeze. His wife, once mortal, is Lokadaya from the village of Layogan, Abra. Apadel or Kalagang is the guardian and dweller of the spirit-stones called pinaing. He can appear as a red rooster or a white dog. The pinaing are stones placed at the entrance to the town to protect the village from invaders and disease. The pinaing are also used as markers placed on sacred ground and under sacred trees. Agonan is a spirit who speaks many languages.

Evil spirits, on the other hand, exert a strong social control over the behavior of the people, whether collectively or individually. For some Tinguian, the kumau can change its appearance at will, taking on the appearance even of the human being it wants to waylay in the forest. For others, it is a gigantic invisible bird that abducts people and steals their things. Maganawan lives in Nagbotobotan, which means “the hole where all streams go”; he can demand the Sangasang ceremony by sending a plague of snakes and birds to a village. Inawen, who lives in the sea, has strange food cravings because she is pregnant but can be appeased with offerings at the Sangasang ceremony. Her servant is nine-headed Kideng, who is tall and fat but the bearer of the people’s gifts to his mistress.

Some of the most fearsome spirits are those that go to the wake to prey on the corpse or its mourners. Kadongayan likes to deform the faces of corpses at wakes: thus, the family in mourning must distract him from the deceased with a live chicken tied to the door of the house. Ibwa has a taste for the liquids and meat of a corpse; and Selday has a taste for its blood. Akop, which has no torso but has a head and long, slimy limbs, can cause the death of the widow or widower during the wake by hugging him or her.

There are also groups of spirits who can do good, cause mischief, or simply be neutral. The inginlaod are spirits of the west. The alan are winged, flying, half-human-half-bird beings. Their toes face backward, and their fingers, also facing backward, are directly attached to their wrists. They hang from trees like bats but also live in opulent houses. Their relationships with people can range from friendly to hostile. The sasagangen, also known as ingalit, are head takers and are the cause of headaches. The ibal cause children’s sickness. The abat, dapeg, balingen-ngen, benisalsal, and kikiba-an variously cause illness, sore feet, headaches, and bad dreams. Each of these types of spirits is appeased by ceremonies specific to them.

There is only one person who has the power and ability to communicate with the sasailo: the alopogan (shaman), usually a middle-aged woman. In rituals of communication with the spiritual world, the alopogan is possessed by the spirits who guide and inspire her words and her actions. The alopogan presides in the various rituals and ceremonies held by the Tinguian.

It is the alopogan who knows which diam (ritual utterances) to use in order to win the favors of the deities for whom the ritual is held. The sacrificial animal is either a pig or a chicken. A mixture of blood-and-rice and sugarcane or rice wine are offered to the spirits, but most of the meat and wine are served to the ritual participants. The shamans call upon the spirits to enter their bodies; when thus possessed, the shamans are transformed into the spirits themselves and they speak to the people as such, replying to queries and giving counsel.

The Tinguian also build elaborate structures and employ various paraphernalia for the rituals held to cure the sick and to honor the dead. The say-ang is the most important of their ceremonies; it is observed during the construction of the balawa, the biggest anito dwelling used for curing sickness and the performance of magical rites. At the entrance to the head takers’ village, each head was displayed on top of a sagang, an eight-foot-tall bamboo pole that was sharpened to a point at the top end, to secure the head. A more elaborate holder for the head was the saloko, also called salokang or sabut, a 10-foot tall bamboo pole, the top of which was cut into vertical strips that were pressed open and interwoven with other strips to form a basket. After three days, the village held a victory celebration, with neighboring villagers as guests. For this festival, the heads were transferred from the village entrance to the site of the festival.

With the decline of head taking, the saloko became a container of food and betel-chew offerings for the spirits. Thus, it could also be a square structure made of four bamboo poles serving as corner posts holding up a square wooden tray for the spirit offerings. If it stands beside a house, it may be a ritual cure for a headache; if in the fields, it is the dwelling of Kaiba-an, the spirit guardian of the rice fields. The function of the saloko as a receptacle for a head and its sacred function in the rice fields indicate that head taking might have been a ritual offering before the rice-planting season.

Other rituals over which the alopogan presides are the sugayog, dawak, calangan, and bawbawa or calcapao, which aim to combat the influence of evil spirits, as well as attract the intercession of benign anitos.

The kadawyan or kadauyan (beliefs and practices) represent the collective wisdom of the Tinguian ancestors and as such are greatly revered. Those violating the kadawyan and traditional kanyaw (taboos) are punished by the anito and the kal-kalma or ap-appo (spirits of ancestors) in the form of balos or lebek (evil curse). These punishments come in the form misfortune, sickness, or death.

Christian conversion of the Tinguian began in 1730 through the process of forced resettlement called reduccion. Between 1823 and 1829, Augustinian Fray Bernardo Lago established the mission of Pidigan in Abra province for at least 8,000 colonized Tinguian and Igorot. However, over the next centuries, the Tinguian intermittently abandoned these villages and returned to their traditional religious practices.

Presently, the Tinguian population is almost wholly Roman Catholic. A typical example is the population of Abra’s northernmost municipality, Tineg, which consists of the Tinguian subgroups of Adasen, Banao, Binongan, and Mabaca, with some Ilocano families scattered over the area. The dominant ethnic group and language here is Adasen. The Roman Catholic population in this municipality is 99.7%.

Tinguian Houses and Community

Tinguian settlements are located in Abra. In the past, however, the Tinguian belonged to the Apayao district of Cagayan, where they built both bamboo and wooden houses. Bamboo was brought down by the Tinguian migrants over the ridge of the Cordillera range toward the Abra Valley, where they have since established their settlements.

|

| Tinguian village (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The Tinguian had two types of houses in the early 19th century: a daytime dwelling, which was a small cabin made of bamboo and straw, and a nighttimedwelling called alligang, which was smaller and perched upon great posts or atop a tree, about 18 to 24 meters above the ground. This was a precaution against surprise nocturnal attacks by the Guinanes or Guinaanes, their mortal enemies from the village of Guinaang, Kalinga. With continued pacification campaigns of the Spaniards, however, the Tinguian were subsequently drawn to the settled life in small separate villages. Gradually, the tree dwellers became town dwellers.

At present, Tinguian houses are usually built in clusters near their fields. The rice granaries and vegetable patches are located along the boundaries of these clusters. A Tinguian village generally consists of two or three such settlements situated near one another. Toward the lowlands, and especially in Christianized areas, Tinguian dwellings have a more contemporary design while retaining some features of indigenous architecture. Now, some well-off Tinguian families have houses of wood, with capiz windows and galvanized iron roofing.

In the uplands and in the interiors, however, Tinguian architecture has remained basically unchanged, relying on cogon grass for roofing; bamboo for framework, sidewalls, and flooring; and hardwood trunks for the main house posts. The general appearance closely resembles that of the nipahut in the Philippine rural area.

Like other Cordillera houses, a Tinguian dwelling would have a single room that contains the sleeping quarters and the hearth for cooking food. Some have a separate smaller structure for the kitchen, connected to the house by the bangsal (bamboo bridge). Sometimes the one-room house is surrounded by a porch of bamboo. In traditional Tinguian houses, the flooring of the house is made of bamboo slats. Through these slats the bride and groom are expected to push a small quantity of ceremonial cooked rice, as an offering to the spirits. Some Tinguian families add a patagguab or a smaller room as an extension to their home. There is one feature, however, which distinguishes the Tinguian house, even the more contemporary ones. One corner of the house, constructed of bamboo with bamboo slats for flooring, is reserved for the mother when giving birth to her child.

The Tinguian rice granary resembles its Isneg counterpart, from which it may have been derived, since the Tinguian used to occupy a territory that was part of Apayao. The Tinguian granary has walls that flare outward, a design that makes it difficult for field rats to climb in. The foundation of these granaries feature four girders mortised across one another on the same level, with their ends protruding beyond the joint. Granaries are built away from settlements to protect them from fire.

Aside from houses, the Tinguian also build chicken houses and sheds for domestic animals. They also erect the miniature spirit houses for sasailo and the spirits of their dead relatives. Mostly found at the outskirts of towns, these spirit houses contain various offerings for the sasailo, such as boiled rice, chicken liver, and other food.

There are no structures in the Tinguian village for bachelors, nor are there dormitories for girls. Instead, there are elaborate ritual structures erected for special occasions like the say-ang. Among these are the balawa, a big temporary structure built for the anito near the house of the celebrant. Its uses, however, are not merely spiritual. It also serves as a meeting place for the womenfolk and as a center for economic activity. Another structure, the kallangan, is a simpler version of the balawa, which is constructed by people of lesser means. Other structures built for the say-ang are the alalot, made of bamboo arches supporting a grass roof; the aligang, where basi and other offerings are placed; and the ansisilit, a structure placed near the pinaing or guardian stones. In all, around 18 structures are built for the say-ang and other less important rituals. There is also a mausoleum-type of small structure lined with stones for the reception of multiple burials, found beneath the Tinguian house.

Tinguian Traditional Attire

The first material used by the Tinguian for their clothing was the bark of trees, which they used to fashion headbands, loincloth, and containers. With the introduction of cloth, Tinguian weavers eventually produced the male suit called the ba-al (clout), worn together with the balibas (woven shirt). On special occasions, a bado (long-sleeved jacket) is also worn with this suit. A traditional headgear made from bamboo with a low dome-shaped top reminiscent of the lowland salakot completes the male costume. The female suit consists of a short-sleeved jacket with a narrow skirt extending from the waist down to the knees, with a girdle attached to a clout in the case of adolescent females. Other traditional attire for women include the kimona (sleeveless short blouse) and tapis (skirt), which can either be a gamit (colorful striped or checkered skirt) or a dinniwa (plain white skirts with red border stripes). The dinniwa is worn on special occasions.

|

| Upper-class Tinguian woman (A Philippine Album: American Era Photographs 1900-1930 by Jonathan Best. The Bookmark, Inc., 1998. Colorized by Alex Lim, 2017) |

Both males and females practice body tattooing. Among women, tattooing of the arms conceals the marks left when they remove the strands of beads covering their arms from elbow to wrist (see logo of this article). The older generation of Tinguian women had themselves tattooed on the arms, from the wrist to the shoulder, as well as on their faces. In 1887, the tattoo, which the Tinguian received when they were seven to nine years of age, was made by cutting the skin with four or six bundled needles and inking the wound with oil mixed with burnt and pulverized, blue cotton cloth. Designs were adapted from their natural environment, such as snakes and birds, and visible natural phenomena such as stars. These covered their bodies down to their knees. The tattooed Tinguian skin was smooth and did not have a scarred look.

Tinguian women wore several sets of beads: one around their hair paired with brass earrings, one around their necks, and another around their wrists. Often, another set of beads was slung over the shoulder and went under the armpits. A piece of jewelry that doubles as a charm to ward off evil spirits is an ornament with an ambiguously carved animal figure.

Tinguian Arts and Crafts

|

| Pattern used in Tinguian blankets, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

The Tinguian are particularly noted for their creative designs in weaving, bead making, basketry, and pottery. They weave their cloth from locally produced material using simple but effective equipment. While the old handheld loom is still used in some places, most of the local weavers now use the modern spinning wheel. The weavers produce the multicolored tapis, aside from other articles of clothing. The balwasi (female blouse) is made from abel (woven cloth). This is basically white, with polychrome stripes at the center. The bankudo or piningitan is a wraparound skirt for women, which is all white except for a red strip at the edges. Another common product of the loom are blankets, which use a wide variety of designs, like male and female figures, flowers and plants, animal motifs including horses, goats, and fish. Many of these Tinguian “death blankets,” which are considered heirloom pieces, are fast disappearing, snapped up by foreign and local treasure hunters from Tinguian houses.

|

| Pattern used in Tinguian blankets, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

|

| Pattern used in Tinguian blankets, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

Motifs, which include animal figures like snakes, lizards, and birds, and geometric and floral designs, are incised on bamboo instruments and wooden pipes. Tinguian pottery, on the other hand, is decorated with scroll-like designs. Another craft for which the Tinguian are noted is beadwork. Heirloom beads, many of them remnants of an ancient trade, are strung with other local beads to create a fascinating variety of combinations and patterns. Women traditionally wear the balsay (bead bracelets) from wrist to elbow.

Baskets are used for storing food, carrying crops, bringing trade products to the lowland areas, and similar purposes. These are seldom adorned with decorative motifs. Aside from the baby’s rattan basket cradle, which is universally found in all of the Philippines, the Tinguian make galong-galong, a wooden baby’s swing, which can also alternate as a walker. This is made of a bamboo frame with a flat wooden seat, to which bamboo reeds, cut at even lengths, are vertically attached to one another with split rattan. It is hung from the house’s roof beam. The height at which it is raised from the floor can be adjusted so that it can function either as a swing or a walker.

Tinguian Calendar

The ansit is a Tinguian calendar described in poetic form among the Gobang subgroup of the Tinguan in the municipality of Bangilo (Anima 1982):

Upoc

Lumtao kad si Upoc

Mantaltalpoc lapoc.

Kiang

No adi making dolmangan

Gapus tungnina coman

Kiang ngadan dim bulan.

Ladao

No bulan kad di Ladao

Sawali kanda uma

Dida umoy miyalgao.

Kitkiti

No buminak kad din udan,

Mangkitiyan di pispisan;

Ot no ina kad naligat

Mangkitiyon di apuy si ginboat.

Panaba

Lumoaoan di panaba

Tumabaan di mula,

Nigay, dumloc kan palwa.

Adawoy

Al-algao si Adawoy

Anandon mawaoywoywoy

Napia t said umoy bumgasan

Di pulot, alig kanda iyukan.

Akal

Akal—

maowalnacan cutiil,

maac-aclan di ata bitil.

Umya maacal dam palilong.

Mamagitong

Dumatong kad si Mamagitong

Gumitong dam palilong;

Masa-ultam mangawit.

Umya siya umoy magutongan

Di tubu-tubun adduwan

Kanda lamota mila-it.

Kabukao

Dumatong kad si Kabukao,

Siya umoy mabukaoan

Di imboy di gassilan,

Mummuno, loda, kanda talgadao.

Walu

Walu—

mantimpapalu dan al-u;

nakwa langpadan canu.

Kadya—

sagana-on di tagu

balin maowallu-wallu

Kiling

Magulli-gullinganan di

cublit si amiyan;

Kadagdagu no tumbling

Madubdubana dingding.

Luya

No sumaal bulan di Luya,

Maluya upec di laya.

Kadya mandoyya-doyya

Namol di cadaoa kanda.

(January

When January appears

Dust flies to and fro.

February

If people cannot wade in the river-crossing

Because of biting cold,

The name of the month is February

March

If it is the month of March,

The supplementary rice planting and the kaingin

Occupy people the whole day.

April

If the rain pours,

It is the sound of dropping water from

the roof-eaves;

In dry weather

It is the sound of fire blazing in the forest.

May

The time when the riverbugs appear.

When plants and grasses grow verdant,

When hunted animals put on fat.

June

Days of June

are long stretched.

It is good because it is the time

When different beehives become full.

July

July—

the time when famine spreads,

when eyes become hallow with hunger.

But the palilong fish come out.

August

When August comes

The palilong fish decrease;

‘Tis vain to use hooklines.

But all sorts of mushrooms

Abound;

As also edible root-crops.

September

When September comes,

That is the time

When corn and the various reds

Start blooming

October

October—

sounding pestles vie with one another;

kaingin rice has been harvested.

And then—

people expect

many raging storms.

November

People’s skin is striped

because of the northwind;

We listen with nostalgia

To the hissing breeze upon the house walls.

December

When the month of December arrives,

The ginger is easily peeled off.

And then the eggs of the cadao frog

Are in abundance.)

Tinguian Epic and Folktales

The Tinguian epic is chanted in the rice fields during harvest time to provide respite from the monotony of work. It is also recited by the fire or hearth to entertain the weavers, the makers of rope, or the shell polishers who make cups and bowls. Kanag Kababagowan recounts the life and times of Apo-ni-Tolau, Apo-ni-Bolinayen, and their son Kanag. It is an extended narrative of events woven around the exploits and tribulations of heroes and heroines in Kadalayapan and Kaodanan. These are collectively called “the stories of the first times” and are actually made up of several stories which may be related separately, depending on the storyteller. The epic features an assortment of mythical creatures: spirit-birds; spirit-helpers (or guardian spirits); the alan, a tree-like man who waylays hunters in the mountains of Matawetawen; banaw-es, alikadkad, or dagimuano, magical betel nuts and perfumes which can revive the beheaded, like Kanag; a ten-headed giant who builds his roof from the hair of his victims; and a rooster who rides a burial raft on the river, announcing to all the identity of the dead person.

|

| Various mythical creatures in the Tinguian epic Kanag Kababagowan (Illustration by Jap Mikel) |

The Dulimaman is an epic of thirteen songs or cycles, which tell of the adventures of three generations of heroes belonging to the dulimaman class. It is sung in the Inlaud language in Nueva Era, Ilocos Norte, and Cabugao, Ilocos Sur. The first-generation parents are Atas and Dinawagan, who have nine children—five sons and four daughters. One cycle or song is about Agimlang, the youngest child of Atas and Dinawagan, thus a second-generation dulimaman. Agimlang engages the warriors of Apayao in battle and wins with the aid of his supernatural weapons. Supernatural events, such as the sudden appearance of a bamboo grove and an overflowing river, abet him. He goes home to his village, where he is given a successful head taker’s welcome, including feasting and dancing. Heads are displayed on bamboo poles, and Agimlang recounts his feats. He also brings home a dulimaman as a prospective wife for his elder brother Diwaginan. The wedding feast is held in Diwaginan’s village home and the elders recount the courtship rites, the focus of which are the negotiations for the sab-ong or dowry.

The second-generation hero is Ligi Wadagan. In “Ti Paspasyal ni Ligi Wadagan ken ti Ay-ayam na a Dumaygawan” (The Journey of Ligi Wadagan and his Love for Dumaygawan), the magic bird Dumaygawan flies the newborn Ligi Wadagan to the house of his alimban aunt during a battle between the Tinguian and the Apayao. As a young man, he is courting Babai nga Dulimaman (Dulimaman lady) when he accidentally cuts himself and dies. His corpse is placed in a tabarang or balangay, an indigenous boat, and set adrift on the river, where a female shaman, Kallupayan, finds him and restores him to life. He and the dulimaman lady are married. Woven into the storyline of this epic cycle are Tinguian cultural items and traditions such as the use of the betel chew during courting; an inangkilisan, which is a red cloth for binding a wound; funeral rites; heirloom beads; shamanic practice; the gong; the sab-ong; and wedding rites.

“Apo ni Bolinayen” highlights the Tinguian people’s pride in their weaving artistry and their expertise at farming. However, these become the envy of the Ilocano people, who persecute the principal characters, Ligi Wadagan and Ayo, thus forcing them to flee to the place that is now Nueva Era, Ilocos Norte.

“Istolya ni Gumigiteng” (The Story of Gumigiteng) continues with the story of Ligi and Ayo, who are now happily married. Ayo’s pregnancy causes her to crave the egg of the lablabugauen (wild fowl), which is owned by the man-eating giant Gumigiteng of Namsangan. Ligi goes in quest of the lablabugauen and receives a magical flying binassaan (richly brocaded cloth), from a pair of alimban. However, Ligi dies after he obtains the lablabugauen’s egg. Years later, Ligi’s son, Balballokanag, avenges his father’s death and restores his father back to life.

|

| Apo-ni-Tolau, riding a basket and leaving his wife, to be with his lover, the star maiden Gaygayoma (Illustration by Jap Mikel) |

Tinguian mythology contains a host of characters who play out the relationships between the sky dwellers and the mortals on earth. One story relates how the beautiful maiden Apo-ni-Bolinayen “was pulled up by a vine that curled mysteriously around her body and deposited her in the yard of the sun god” (Demetrio 1991, 62). Another story relates how the star maiden Gaygayoma lowered a basket from her celestial abode for the earth dweller Apo-ni-Tolau to ride up to heaven, where the two eventually married, while the man’s wife was left on earth. Other myths explain natural phenomena by the literary device of personification: Kidol is the spirit of thunder, although another myth identifies thunder as Kadaklan. The two types of lightning are Salit, which is lightning from the sky, and Kilawit, that from the ground.

The Tinguian have their own version of the great flood, which is a universal myth. Here, it also tells of the origin of the human race. The dulimaman warrior Apo-ni-Tolau goes down one day to the lowlands until he reaches the sea. He builds a raft made of rattan and rows out to the edge of the world, where the sea and sky meet. There, he sees a towering rock, where the sea god, Tau-mari-u, resides, guarded by nine daughters of the seaweeds. Apo-ni-Tolau catches the youngest maiden, Humitau, with his magic hook. She struggles until she is weakened by the hook’s magic oil. Apo-ni-Tolau escapes with her on his raft. Tau-mari-u is enraged at her abduction and calls for the waves and the tunas to rescue Humitau. Apo-ni-Tolau’s mother, Lang-an of Kadalayapan, the goddess of the wind and rain, comes to her son’s rescue and pulls his raft ashore. Tau-mari-u calls a meeting of the gods and spirit of the seas and the oceans, and they all agree to punish all land dwellers for Apo-ni-Tolau’s treachery. Knowing that a great flood is soon to come, Lang-an bids her son escape with his household to the highest mountain in the Cordillera. The flood fills up the valleys and plains, destroying crops and killing work animals. Then the floodwater surges up the mountain where Apo-ni-Tolau and his household have sought safety. Humitau, who has lost her powers as a sea diwata (spirit) because she has tasted her husband’s mountain food, cries out to Tau-mari-u. The lord of the sea mercifully calls back the floodwaters. But he vows that thenceforth, he would sink boats and drown people in retribution for Apo-ni-Tolau’s deed. After the deluge, Apo-ni-Tolau and Humitau come down the mountain, and their children become the first people of the world.

Some Tinguian fables share common motifs with those that are widespread throughout not only the Philippines but also Southeast Asia, such as the tale of the trickster monkey and the turtle who outwits him, and the tale of the race between the shell and the carabao. Fables that seem to be of foreign or Ilocano origin are nonetheless rich in Tinguian customs and beliefs.

Tinguian Traditional Music

Tinguian music is an activity of communal life associated with the rituals of life and death. This music is “characterized by ancient elements: recurring rhythmic patterns, continual repetitions, formula opening and closing phrases, and the modest use of four or five tones repeated in sequences within the narrow span of an octave” (Samonte-Madrid 1977, 437).

|

| Tinguian men playing bamboo instruments (Cole 1922) |

The Tinguian have many types of musical instruments, as well as songs, which are shared with neighboring Cordillera groups, particularly the Kankanaey, Kalinga, and Bontok. As in any indigenous setting, there is an integral and harmonious performance of instrumental music, song, dance, and ritual of a participatory nature. Thus, the gangsa is played, the tadek or the da-eng is danced, and the salidummay is sung during the celebration of a lay-og, a bagongong (wake), or a polya (wedding feast).

The gangsa is a gong made of brass and iron. It is flat and varies in size, the smallest being 30 centimeters in diameter, and the largest measuring 40 centimeters . The rim is about 1.7 centimeters thick. Like the gongs of the other Cordillera groups, and unlike those of Mindanao, the Tinguian gangsa has no central boss or incised surface decorative motifs. Gangsa playing is basically a rhythmic ensemble performance. There are different ways of playing the flat gongs, using hands, sticks, or a combination of hands and sticks. There are at least three styles of ensemble playing, heard especially during festive celebrations. These are suklit or sinuklit, pal-luuk or pinalookan, and pinallaiyan or inilaud.

|

| Tinguian flat-gong ensemble, 1980 (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

In gangsa suklit, the ensemble consists of a set of five to six flat gongs of graduated sizes laid on the laps of male performers who use their open palms to sound the instruments. The gongs have specific names, and they have interlocking patterns of play to produce the rhythmic pattern. The first and lowest pitched gong is the balbal or barbar, followed by the kadwa, the katlo, the kapat, and the pokpok, which plays a staccato sound at regular beats; the sixth and highest-pitched gong is the balwawi, which creates varied patterns in relation to the resultant melodies produced by the lower gongs. This particular flat gong accompanies dances which all fall under the tadek type.

The second flat gong ensemble is the gangsa palluuk, in which all the gongs are struck with sticks on either the inner or outer space. The gangsa palluuk consists of five or as many gongs as are available. This is played by men who dance as they strike their gongs and who are then joined by a group of women dancers.

The third Tinguian ensemble is the pinallaiyan or inilaud, which consists of three to four flat gongs and a cylindrical double-headed drum called tambol. The name pinallaiyan is said to refer to the gong-drum ensemble in Abra’s western highland areas, while the inilaud, taken from the word lagud meaning “west,” is used in the ensemble playing of the western and lowland areas of the province. The technique of sounding the gongs in pinallaiyan combines the use of hands and sticks. The names of the four gongs with their respective playing techniques are talukatik, a gong laid on the ground and struck with two sticks; pawwek, a gong held by its string in a vertical position with the lower rim sitting on the ground and struck with one stick on the inside; bugalu, a gong held on the ground and struck with a stick in one hand; and the fourth and largest is the kib-ung which rests on the player’s arm and is beaten on its surface with an open palm. The ensemble’s tambol—from the Spanish tambor, meaning “drum”—is played with two sticks which strike only one of the two drumheads.

Tinguian flat-gong music is often simulated on a bamboo tube zither called kulitteng, also called kuriteng or kulittong, with four to six strings lifted up from the instrument’s hard bamboo skin. One particular way of playing the tube zither combines the plucking of strings with the fingers of one hand and striking one or two strings with a stick held by the other hand. Another Tinguian technique is for two performers to play the tube zither, with one player plucking the strings using both hands and the other player holding the opposite end of the bamboo tube while knocking on the tube’s body with the knuckles of one hand, in prescribed rhythmic patterns. The third style of playing the kulitteng is by simply plucking the strings with both hands, a style found as well among the neighboring Bontok and Kalinga.

The patpattong, a leg xylophone composed of five bamboo blades of graduated sizes and played solo by children using two sticks, is another instrument that simulates the flat gong. Other types of ensembles performed by the Tinguian consist of groups of bamboo instruments such as the patangguk (quill-shaped tubes), played during the forging of peace pacts; tongatong (stamping tubes), commonly used in most rituals; and the bilbil or balingbing (bamboo buzzers) which are played to assuage feelings of sadness.

The saysay-up ensemble consists of six bamboo pipes. The lowest-pitched pipe is called a balbal. The specific names of the other pipes correspond to their pitch and position in the ensemble, namely, makadwa (second pipe), makatlo (third pipe), kapat (fourth pipe), lima (fifth pipe), and anem (sixth pipe).

|

| Tinguian women singing, 1980 (Felicidad A. Prudente Photo Collection) |

Serenading and courtship are the usual occasions for bringing out the solo aerophones played by Tinguian men. These are the paldong or palpaldeng (mouth flute with notch) and the kulaleng (nose flute). On the other hand, the duwas or diwdiw-as (pan pipe) is normally played by women, usually at night, when its soft plaintive sounds travel far. This instrument consists of six to seven open bamboo tubes, of varying lengths and diameters, lashed together.

The Tinguian also have the mouth harp made of bamboo, which is called ullibaw or kolibaw. The one made of metal is called agiweng, while the other type made of brass is called kalibu. Traditionally played by hunters, the mouth harp is believed to induce the pittogo birds to excite wild pigs and deer so that they might move through the forest, thus making them easier to trap. A functionally related instrument is the tabangkaw (musical mouth bow), which is played to call upon the spirit Kabunyan to help the men stage a good hunt. The Tinguian also play a violin made of bamboo or wood. This is the labil or nabil, which has three to four metal strings, which are bowed with a goged. It is played on various occasions for entertainment and has a repertoire that includes instrumental renditions of vocal music.

Tinguian Folk Songs

Tinguian songs are generally of two kinds: declamatory songs and “known” songs. The declamatory songs include balayugos, ngayowek, and oggayam, which are all improvised songs of welcome and farewell, or songs that have something to teach. They differ only in their tonal range, melodic ornamentation, and verse form. The ngayowek is closest to free verse. In singing, the performer’s voice follows as closely as possible the inflections of regular speech. The balayugos is a declamatory song for dignitaries or those of distinguished status. Like the ngayowek, it is more condensed than ordinary speech, not repetitious but very oratorical. These songs are suited for men’s voices. On the other hand, the oggayam is the most commonly used, being the most familiar to other groups. It has a wider melodic range. The rhyme scheme is free verse, with a preponderant use of the terminals am, em, en, and an.