The Isneg (Isnag) Tribe of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Cordillera Apayao Province Indigenous People | Ethnic Group]

The Isneg, also Isnag or Apayao, live at the northwesterly end of northern Luzon, in the upper half of the Cordillera province of Apayao. The term “Isneg” derives from a combination of is, meaning “recede,” and uneg or “interior.” Thus, it means “people who have gone into the interior.” In Spanish missionary accounts, they, together with the Kalinga and other ethnic groups between the northern end of the Cagayan Valley and the northeastern part of the Ilocos, were referred to as “los Apayaos,” an allusion to the river whose banks and nearby rugged terrain were inhabited by the people. They were also called “los Mandayas,” a reference to an Isneg word meaning “upstream.” The term “Apayao” has been used interchangeably with “Isneg,” after the name of the geographical territory that these people have inhabited for ages. The province of Apayao, however, is not exclusively peopled by the Isneg. There has been a large influx of Ilocano over the years. From Cagayan, the Itawit have entered and occupied the eastern regions. The Aeta inhabit the northern and northeastern parts of the province. And then there are the Kalinga, a major group in the province south of Apayao.

The Isneg have always built their settlements on the small hills that lie along the large rivers of the province. This whole territory used to be two sub-provinces, Kalinga and Apayao, when the whole of the Cordillera region was still a single political subdivision. The Kalinga group occupies the southern half of the consolidated province. With the former capitol located in Tabuk, Kalinga, much of the economic and political activity in the province was concentrated in this southern half. Sharing the same territory with the Isneg are the Aggay, about whom little has been written.

To the northwest of the province, occupying mostly parts of the mountainous eastern border of Ilocos Norte, live the Yapayao. The Yapayao are descended from the Apayao group that fled Spanish colonialism and settled at the source of the Bolo River, deep in the mountains of Kalinga and Apayao. This group eventually split into two: the Isneg, who moved downstream, and the Apayao, who remained by the Bolo River source. The Yapayao is a subgroup of the upstream Apayao who later moved to Ilocos Norte, specifically to the two towns of Dumalneg and Adams.

In 1988, the Isneg were estimated to number around 45,000. In 2000, their population in Apayao was at 32,451, comprising about 33% of the predominantly Ilocano province. Municipalities occupied by the Isneg include Pudtol, Kabugao, Kalanasan, and Conner. Two major river systems, the Abulog and the Apayao, run through Isneg country, which until recent times has been described as a region of dark tropical forests, endowed with other natural resources. In one early account, the Isneg were described as of slender and graceful stature, with manners that were kindly, hospitable, and generous, possessed with the spirit of self-reliance and courage, and clearly artistic in their temperament.

History of the Isneg People

The Isneg’s ancestors are believed to have been the proto-Austronesians who came from South China thousands of years ago. Later, they came in contact with groups practicing jar burial, from whom they adopted the custom. They later also came into contact with Chinese traders plying the seas south of the Asian mainland. From the Chinese they bought the porcelain pieces and glass beads, which now form part of the Isneg’s priceless heirlooms.

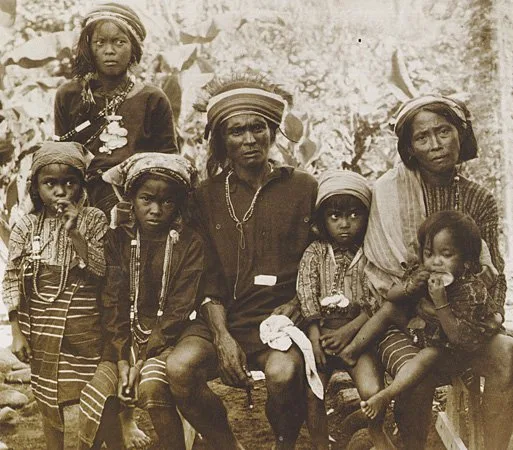

|

| An Apayao family (A Philippine Album, American Era Photographs 1900-1930 by Jonathan Best. The Bookmark, Inc., 1998.) |

The Isneg have been known to be a head-taking society since recorded history. The colonial regime of the Spaniards sought to curb this practice and to fully Christianize the mountain people. The Spaniards were able to put up three missions in 1610, but these were abandoned in 1760.

A Christian mission was established in Capinatan in 1619. In 1625, the first of a series of short-lived uprisings began. The Isneg of Capinatan and those of nearby Fotol—now Pudtol—staged a rebellion, led by their chiefs Don Miguel Lanab and Alababan. They entered the convent, where Alababan beheaded one of the two priests, Lanab severely wounded the other, and three more Isneg rebels finished him off.

In 1631, Father Geronimo de Zamora resumed mission work among the Isneg upstream among the Mandaya and rebuilt the Capinatan church the following year. A short-lived uprising arose in 1639—the commander of the Capinatan-Totol garrison had punished an Isneg woman, who was of noble rank. Already resentful of Spanish oppression, the members of her village and those of neighboring ones attacked and burned down the garrison, killing all 25 soldiers in it. They allowed the priest to evacuate, taking church objects and garments with him. They then burned down the church and convent before fleeing into the mountains.

An Isneg, Juan Manzano also known as Magsanop, partly led the Ilocos Revolt of 1660-1661. The campaign to eradicate Christianity began with the murder of the missionary friars in Bacarra and Pata. The rebels drank wine out of the skullcap of Father Jose Arias of Bacarra in an old ritual. Then they destroyed Christian religious objects, and Manzano ordered a return to the native religion. The more faithful Isneg converts aided the local authorities in suppressing the rebellion. Manzano and his co-leaders were executed, their heads severed and displayed. In 1662, the Augustinians reached the Isneg up the Bulu River from Bagni and freed them from taxes as a reward for their nonparticipation in the Manzano rebellion. Father Pedro Jimenez erected two stone churches in Pudtol and Capinatan, Apayao, prior to his Cagayan Valley assignment in 1677. He returned to Apayao in 1685 to reestablish peace pacts between feuding villages, namely, the Mandaya and the Christian converts in the colonized towns. Peace had been broken by Darisan, an Isneg from Kabugao, who killed a Spaniard and a Filipino in the guard post of the Capinatan garrison in Pudtol. Jimenez successfully restored the Capinatan-Totol mission. In 1688, the Archdiocese of Manila formally recognized his church in Nagsimbanan, Kabugao.

Governor-General Valeriano Weyler exercised no real power in the two military camps he set up in Apayao and Cabagboan. Spanish military occupation in Apayao failed despite the Spaniards’ use of treacherous tactics. In 1888, Lieutenant Medina’s expedition to the Kabugao area was welcomed by a feast given by Onsi, the local chief. The feast ended with the brutal killing of 17 unarmed Isneg, including the host himself. The Isneg retaliated by killing a party of Ilocano traders. This could also be related to the Isneg attack on Dingras and Santa Maria, Ilocos Norte, in the same year. Three years later, Father Julian Malumbres was sent to Apayao to resurrect the abandoned mission. Before this, the Apayao’s commandant, Captain Enrique Julio, captured several prominent Isneg by inviting them to a feast in Guinobatan, Pamplona. One was killed, several wounded, and the rest imprisoned. Father Malumbres failed to reconcile with the Isneg who were misinformed that he had been the traitor. His two servants were killed, and Malumbres never returned to Apayao. The Isneg defeated the Spaniards in a decisive battle in 1895.

During the American regime, Blas Villamor was appointed commander of a Philippine Constabulary post at Tawit and was charged with the responsibility of curbing the head-taking activities of the Isneg. The Isneg practice of head-taking came to an end in 1913 when the Constabulary subdued them in the Battle of Waga.

In 1908, Apayao had been made a sub-province of the newly created Mountain Province, covering what is now the Cordillera region. In 1913, the sub-provincial capital was transferred to Kabugao. A company of soldiers, including Isneg recruits, was assigned to maintain peace and order and to intercede in disputes that would have otherwise resulted in “revenge expeditions.” Soon after, basic education was introduced, with English as the medium of instruction.

During World War II, northern military operations against the Japanese were launched from the Kabugao headquarters of the Cagayan-Apayao Forces (CAF), a guerrilla organization headed by Captain Ralph Praeger of the former Philippine Scouts. By 1943, CAF had suffered devastating losses, but Captain Praeger was grateful for the reported thousands of Isneg who were willing to join the guerrillas, especially after President Manuel Quezon, then exiled at Lake Saranak, New York, praised their continued support.

Other Isneg also joined American and Filipino guerrillas who operated in Cagayan Valley and south Cordillera. Although the practice of head-taking had been outlawed a generation before, the war revived the practice, with the hill people, including the Isneg and Yapayao, presenting Japanese heads and ears as proof of their contribution to the Allied war effort. Their exploits, including their collection of Japanese skulls, would later become the subject matter of their chants in postwar social gatherings. After the war, most of them would become pensionados who received money from the US government for their wartime service. To the Isneg, this meant an assurance of education and a better future for their children in a province that was eager to rise from the ravages of war.

Kalinga and Apayao, consolidated as a single province in 1966, became part of the Cordillera Autonomous Region (CAR) in 1987. In 1995, the two distinct geographical locations were reverted into separate provinces with the enactment of Republic Act 7878. At present, Apayao’s municipalities include Kalanasan, Conner, Flora, Pudtol, Luna, Santa Marcela, and the provincial capital, Kabugao.

The Isneg are adversely affected by the armed conflict between the Philippine government and the Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP). In 1986, the Philippine government adopted a nationwide hamleting strategy that had been used by the American government in the Vietnam War. In December of that year, ten months after the EDSA People Power Revolt in Metro Manila, a battalion of soldiers entered the village of Kelayat, which the military claimed had been infiltrated by the New People’s Army, the military arm of the CPP. At least one Isneg woman died as a result. Similar incidents happened at Marag and Paco Valleys the following year, resulting in the mass evacuation of Isneg as well as Atta families who also resided in these areas.

In the same year, 35 Yapayao families—176 individuals in all—were forcibly evacuated from the mountain village of Saliksik in Pagudpud, Ilocos Norte, to the lowland town of Dumalneg, which was also populated by Yapayao. In 1990, the evacuees gradually resumed cultivating their kaingin farms around Saliksik, traveling the 10-kilometer distance daily, sometimes temporarily staying in makeshift shelters in their kaingin fields. By 1992, they had moved back to Saliksik. Within the same year, after a 10-year application, most of the families who had resettled in Saliksik qualified for Certificates of Stewardship from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR), giving them legal rights to farm their land for the next 25 years, renewable for another 25 years.

Isneg Tribe Way of Life

The Isneg’s main staple is rice, which they have traditionally produced in abundance. This is raised through slash-and-burn agriculture. There has always been a surplus every year, except in rare instances of drought or pest infestation. The Isneg’s main source of sustenance is dry rice culture, which is suitable for the semi-mountainous and tropical, vegetal terrain of Apayao. This is what they have in common with the Kalinga, the Gaddang, and the Bugkalot (Ilongot). Other culture groups in the Mountain Province practice terraced wet-rice culture, a combination of dry-rice and wet-rice culture, or root-crop agriculture in addition to rice cultivation. Unlike other Cordillera peoples, both the Isneg and the Kalinga almost never resort to root crops as a substitute for rice. In times of meager harvests, they would resort to trading their locally made products like hats, baskets, and pots, with people from other areas for rice.

|

| Isneg farmer, 2014 (Edwin Antonio, ilocandiatreasures.com) |

Apart from rice, other crops raised are corn, taro, sweet potato, sugarcane for making basi (sugarcane wine), bananas, yams, and fruit orchards. Tobacco and coffee have become principal crops in Apayao since the 1960s. The tanap (plains along the river) of Binuan are known to yield high-quality tobacco. Twenty percent of Cordillera’s tobacco and 25% of the whole region’s non-Arabica coffee originate from the municipalities of Calanasan, formerly Bayag, and Kabugao. Planting, weeding of the fields, harvesting and storing of rice, as well as the planting of yams and other tubers, are all preceded by appropriate rituals and ceremonies albeit now greatly simplified and minimized.

A standard ritual is simply to leave a ritual offering of mamaen or betel chew in one spot of the uma (farm). The chew is composed of betel nut, lime, and water. Before planting, the family offers a sacrificial chicken or a boiled egg, depending on what they can afford. A dead relative who appears in one’s dream must be offered a ritual meal of rice and other items of food to prevent them from disturbing the uma. Before harvest, the farmer uses a rakem (single-bladed knife) to cut eight-inch long palay stalks so that he can tie them into a two-inch thick bundle. He leaves this bundle in the granary to invoke the spirits and to ensure an ample supply of seeds for the rest of the year.

There are Isneg equivalents for the calendar months, according to the various stages of the koman (planting field) activities in Karagawan, Kabugao: In January, kihing (cool weather) is for planting tobacco and vegetables; in February, uku, when wild animals are less active, is for clearing the koman; in March, kiyang, when animals start to appear, is for burning the koman; in April, ludaw, when buds of fruit trees start to grow, is for planting rice and clearing burnt wood; in May, bakakaw is the beginning of planting; in June, kitkitti, when it is hotter and more humid and fruits have ripened; in July, banaba (showery) signals the beginning of the rainy season, and the planting and weeding of the rice field; in August, akal is for collecting wood washed ashore by swollen rivers; adaway, in September, is when crops grow fast; in October, bisbis (sprinkling water) is how fibers for bundling palay are prepared; in November, kamadoyong (sound of heavy rain) is when palay is harvested before rivers are flooded; and loyya (sad), in December, cold days are for filling the granary with rice, and for planting root crops and tobacco.

As the men cut the trees and clear the field for swidden preparation, so the women plant the rice grains in the kaingin field. With a gaddang (dibble), a sharply pointed stick of hard wood, they make a hole in the ground four inches deep, take a handful of rice grains from a belt bag, drop these into the hole, and sweep the soil over the hole to cover it. Second crops are planted next: okra and beans at the borders of the uma; patola (gourd) and ampalaya (bitter melon) at tree stumps, over which these vine plants can climb.

The hard manual labor required by the kaingin system is eased by the cultural practice of abuyog or ammuyo, a reciprocal exchange of labor and goodwill between at least two families. The host farmer serves the lunch and snacks to his guest workers. In the practice of inkaruan, a creditor agrees to let a debtor pay off his debt with an equivalent amount of work. In recent times, however, the Yapayao, because they are neighbors to lowland Ilocano farmers, prefer to hire themselves out as day laborers for the cash payment.

The Isneg have preserved an elaborate economic culture centered around the concept of land ownership. According to their traditional view, the ownership of land is absolute, governed by an unwritten law of property relations. This law is respected and recognized, enforced and defended by generations of Isneg. Life is materially associated with the land, the forests, and the rivers. The recognized owner of a piece of land has exclusive rights over its natural resources and its fruits. According to Isneg custom law, land is acquired and owned in three ways: the first-use or pioneer principle; actual possession and active occupation; and inheritance.

The first-use or pioneer principle is applied by an individual or clan on the following types of terrain: the bannuwag (swidden); the sarra or angnganupan (forest and hunting grounds); and the usat or angnigayan (water and aquatic resources). Part of the land that can also be claimed for ownership is the land space called nagbabalayan (from balay, meaning “house”), where the owner or his family and clan have resided, and which they have planted with coconut, palm, and fruit trees. Land acquired through possession and occupation includes the swidden farm, residential land, and fishing grounds. All these categories of land can also be acquired through tawid (inheritance).

However, indigenous people’s custom law is not necessarily compatible with Philippine laws on land ownership. An Isneg farmer and his family may suddenly be evicted from their ancestral land by someone with legal claims to the property. A modern solution for hill people like Isneg farmers is the acquisition of a Certificate of Stewardship from the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, which grants them the legal right to use their land for 50 years.

For the Yapayao of Saliksik, the national government’s intervention has brought about changes in their age-old farming methods and lifeways. Slash-and-burn cultivation on the steeper slopes are supplemented by plow farming in the flatter parts of the field, which are converted into wet rice paddies. A natural irrigation system is fed by the river nearby. In the swidden system, second crops were limited to yams, ginger, and anahaw (pandan palm). Relatively permanent fields, however, have led to a diversified farming system. This has produced a variety of crops such as coconut, betel nut, coffee, as well as fruits such as jackfruit, guyabano (soursop), avocado, banana, and citrus. Hence, the farmers’ harvests are not only for their own subsistence but also for the commercial market.

The Saliksik Yapayao’s absorption into the national cash economy has also resulted in their absorption of its worldview. Land is perceived as a permanent and inexhaustible source of wealth and security. Synthetic fertilizers and pesticides are now in standard use. After 1992, three farmers in Saliksik each owned a hand tractor, which they rented out for cash. More families own a motorbike, which transports their goods to the market, instead of the men walking to the market with their meager surplus on their shoulders or the women carrying these on their heads. A greater premium has been placed on the children’s education, the goal being to finish high school.

The Isneg Tribal Life

Isneg society did not develop a form of village leadership strong enough to be recognized as an indigenous political authority by all Isneg communities in the region. A possible reason for the absence of a centralized rule is the small size of villages or hamlets, and thus the small population of males that could be harnessed to form an army strong enough to bring other villages under its control. For ages, Isneg warriors engaged in small-scale ambuscades, not in full-blown tribal war. The taking of a few heads during a raid was in retaliation for some previous wrong or misdeed and not for the conquest of territory. Slavery was unknown, so there was no need to capture people.

|

| Isneg head axe, University of the Philippines Anthropology Museum, 1970 (Filipinas Heritage Library) |

Law and order is maintained by a panau wen (council of elders), which arbitrates and settles disputes among family or village members, and imposes penalties and sanctions on wrongdoers. In the settlement of cases, jars, beads, rice, and animals are used to pay fines or damages. The council is headed by a mengal, more recently called the sarikampo (from the Spanish maestro de campo), who is chosen for his seniority, wisdom, and eloquence. Traditionally, his leadership is measured by the number of head-taking forays he has successfully led.

The mengal may later become kamenglan, the bravest of the brave—the ultimate goal of a human being. The mengal truly enjoys enormous prestige, being a warrior of proven courage. In the past, the mengal wore a red scarf around his head. His arms and shoulders were tattooed to signify that he had taken several enemy heads in battle. He would sponsor the say-am for his people, a lavish feast during which he was expected to recount his martial exploits.

Head taking was itself an elaborate ritual. The warrior killed the enemy before cutting off his head with a special axe called an aliwa. After a day or two, he offered the severed head to the village mengal, and the community celebrated his achievement with a patong (ritual feast) of pigs and drinks, and much singing and dancing. The head-taker performed a dance while holding up the severed head; then, with much oratorical flourish, he regaled the crowd with stories of his head-taking exploits. Afterward, the head was skinned and stripped down to the skull. This was given to the village’s most respected metalsmith or bolo maker, who placed it among other skulls on a rack inside his house. This was why the bolo maker’s house was called ballawa (a place of skull preservation).

Isneg Customs and Traditions

The Isneg woman traditionally gives birth in a kneeling position, using a mushroom as a talisman to ensure a successful delivery. The umbilical cord, cut with a bamboo sliver, is mixed with the rest of the afterbirth, tied up with ginger and herbs, and buried in a coconut shell under the house.

|

| Isneg family (National Geographic, 1912, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The formation of the Isneg family begins with the rites of courtship. The girl’s parents allow this to take place in their house, in their presence. If the suitor has become acceptable to the girl’s parents and to her, he may be allowed to sleep with her. This may last for several nights, and it is likely that a sexual relationship takes place, after which the couple’s parents engage in the manadug or discussion of terms of marriage. The arrangement is called agyan ya lalaki if it is decided that the couple should live with the parents of the woman, gimanlid if with those of the man, and dinoyan if with both sets of parents alternately. Recent years have shown, though, that young Isneg couples prefer sumang nga balay (independent residence).

Also discussed in the manadug is the amount of the tadug (bride-price), which includes Chinese jars or plates, bolos, beads, animals, Ilocano cloth, and coconut trees. The tadug is substantially higher if the couple opts for the gimanlid arrangement. The man may be required to work for the family of the girl for a year or so. This usually happens when the tadug is high but the man is a “desirable acquisition.”

Among the Yapayao, the old way is child betrothal, no longer practiced now. This is arranged by the two families when the children are two or three years old. The wedding is held when they reach puberty, between 12 and 14 years of age. Negotiations for the bride-price are conducted between the two families. The girl’s parents can express their disappointment with the bride-price by ceremoniously cutting a bua (betel nut), which has been wrapped in cloth. Negotiations are hence deferred for another day. The bride-price might consist of all or any of the following: manding (a Chinese heirloom bead); aliwa (head axe); quen or ken (wraparound skirt); ules (blanket); carabao; and a plot of land. The officiant of the inapugan (wedding) is a panau wen, a council elder chosen for his eloquence. The wedding ceremony centers on a betel chew, which is composed of the apug (lime) and a bua. A child between five and eight years old holds out these two ingredients, and the couple each takes any one of these, thus signifying the inseparability of a married couple. A grand feast follows. The bride’s parents and her clan go to the groom’s house to receive the last item of the bride-price. The newlyweds spend their first night in the groom’s house and their second day and night in the bride’s house. The young couple lives with the bride’s parents until they are ready to live on their own.

Isneg society permits polygyny, but not polyandry. In the husband’s succeeding marriages, it is the first wife who acts as the pamo-noan (negotiator) for the manadug (bride-price), thus replacing her husband’s parents in this role. Either the common husband may have the wives live under the same roof or he may build separate dwellings for them. Adultery, however, merits some punishment. The culprits are marked with a sign of their misdeed with a knife cut on their arm or leg, which would leave a permanent scar. The male lover must pay the woman’s husband a mariapa (small Chinese jar) or money.

The common practice of division of labor based on physical strength and gender is evident. The man prepares the clearing for planting. He also engages in hunting, fishing, and the building of houses and boats. Where the metal plow has been introduced in recent times, plowing has been added to his schedule of activities. The woman plants, weeds, harvests rice, prepares the meals, maintains vegetable gardens, and rears children. In the old days, the man built high fences around the house yard to protect the family from enemies and head-taking groups. Since head-taking has ended, these fences are now built low.

In adherence to Isneg custom law governing ownership, husband and wife retain their rights to their own prenuptial properties, while assets acquired jointly by the couple become conjugal properties. These can also be lost or disposed of as damages or fines paid for crimes or offenses committed by any member of their family or clan.

Throughout the year, rituals play a central role in the social life of the Isneg. Their rituals are often very festive occasions. Everyone in the Isneg community prepares and looks forward to the feasts observed during the year, which are related to the most important events in the Isneg’s life: marriage, illness, death, harvest, farewells, political negotiations, or honoring family members for achievements.

An important special ritual is the say-am, which is performed before an assembly of people, for important social occasions, such as a successful headhunt in the past, the removal of mourning clothes, and other events left to the discretion of wealthy families. The outlay in terms of food preparation is enormous and can only be afforded by the rich. To these occasions, shamans and distinguished members of the hamlet such as the warriors are invited. Only one shaman may officiate in the rituals. These occasions, undertaken between long intervals of time and in various places, have been the only group celebrations among the Isneg. These give a larger meaning to their life, unite them, and impart a sense of identity.

In recent years Apayao has been recorded as having the lowest crime rate in the Cordillera region. In 2013, the Philippine Information Agency recognized it as CAR’s safest province.

Isneg Religious Beliefs and Practices

The spiritual world of the Isneg is populated by more than 300 anito (spirits), who assume various forms. There are no gods or hierarchical deities in the otherworld of the Isneg—only good or bad spirits.

|

| An anito figure, circa 1900, attributed to Apayao (Alpha Sadcopen, The Field Museum, Cat. No. 109425) |

The chief spirits are Anlabban, who looks after the general welfare of the people and is recognized as the special protector of hunters; Bago, the spirit of the forest; and Sirinan, the river spirit. They may take the form of human beings or former mortals who mix with the living who reside in bathing places. They may be animals, with the features of a carabao, for example, and live in a cave under the water. They may be giants who live somewhere in the vicinity of Abbil. They may be spirits guarding the foot and center of the ladder going up the skyworld, seeing to it that mortals do not ascend this ladder. Most of these spirits, however, are the souls of mortals and exhibiting human traits when living as mortals. Some spirits can bring hardship into the life of the Isneg. One such spirit is Landusan, who is held responsible for some cases of extreme poverty. Those believed to be suffering from the machinations of this spirit are said to be malandusan (impoverished). But the Isneg are not entirely helpless against these scheming spirits. They can arm themselves with a potent amulet bequeathed to mortals by the benevolent spirits. This amulet is a small herb called tagarut, which grows in the forest but is hard to find.

At harvest time, a wide assortment of male and female spirits attends to the activities of the Isneg, performing either good or bad works that affect the lives of people. There are spirits who come to help the reapers in gathering the harvest. They are known as Abad, Aglalannawan, Anat, Binusilan, Dawiliyan, Dekat, Dumingiw, Imbanon, Gimbanonan, Ginalinan, Sibo, and a group of sky dwellers collectively known as the llanit. On the other hand, there are spirits who prefer to cause harm rather than help with the harvest. These are Alupundan, who causes the reapers’ toes to get sore all over and swell; Arurin, who sees to it that the harvest is bad if the Isneg farmers fail to give her her share; Dagdagamiyan, a female spirit who causes sickness in children for playing in places where the harvest is being done; Darupaypay, who devours the palay stored in the hut before it is transferred to the granary; Ginuudan, who comes to measure the containers of palay and causes it to dwindle; Sildado (from soldado, meaning “soldier”), who resembles a horse and kills children who play noisily outside the house; and Inargay, who kills people during harvest time. When inapugan, a ritual plant, is offered to Inargay, the following prayer is recited by the Isneg farmer: “Iapugko iyaw inargay ta dinaami patpatay” (I offer this betel to you, Inargay, so that you may not kill us) (Vanoverbergh 1941, 337-39).

Between the living Isneg and this pantheon of spirits is the shaman whose function as intermediary is indispensable. The dorarakit or anitowan (shaman) is almost always a woman. She has to undergo a long training, starting from early childhood. She intervenes for the recovery of afflicted persons, performing suitable rites and appealing to particular spirits. In the maxanito ritual, the dorarakit becomes a mataiyan (the one who is ridden upon) or possessed by either an anito or a kaduduwa (spirit of the dead). She also performs séances or propitiatory rituals so often necessary to gain the favor or sympathy of these spirits. Her functions differ from that of the medicine man in other ethnic cultures who uses parts of plants and trees in preparing a remedy for a sick person. The daughter of a priestess may become a dorarakit, one who performs the role of shaman and magician and who is entrusted with the making of tanib (amulets), which ward off evil spells.

Many rituals are connected with the agricultural cycle, the daily life on the swidden, which includes clearing, planting, and harvesting. Nature provides signs and portents that signal the start of specific activities. There are rituals related to life in the swidden, to rice, and to the community as a whole.

Before choosing a piece of land for his kaingin, the Yapayao watches for signs that warn him off the area such as the sight of any kind of snake, whether venomous or not, or the squealing of a deer. A monitor lizard is a portent of an illness in the family or a poor harvest; a kingfisher, of an impending disaster in the kaingin. On the other hand, the Yapayao farmer has a simple ritual for testing the viability of a piece of land: He leaves a piece of ginger on a tree in the land and returns for it in two days. If it is still there, then he can start to clear the land. However, Yapayao farmers who have shifted to plow farming of wet-rice paddies claim that such omens are no longer significant to them.

Three signs indicate that clearing work on the swidden can begin: The red bakakaw herb comes out, the tablan (coral tree) is in bloom, and the leaves of the basinalan tree fall to the ground. This is around February to March. Then, the lumba tree begins to bear fruit, and it is a sign that the dry days have begun, that is, time for burning the swidden. A good harvest is portended by the rising of a little whirlwind from the burned field. This, it is said, is the spirit Alipugpug. This wind fans the fire that moves across the burning field which never goes out of control “because swidden culture has its own ecological wisdom.” Before burning, the Isneg clear the swidden very carefully, taking care not to harm certain plants, such as the amital vine, which must not be uprooted; the lapatulag tree, which is a protection against rats; and the lubo herb, which must not be killed, lest a death befall the offender’s family. The clearing burned, a few seeds of rice are cast into the wind, and a prayer is offered to the spirits. The farmer and his family gather charred wood that has not been completely burned. This will be used for fuel, to be used during the harvest. Three days before rice is planted, the agpaabay ceremony is observed. A man and a woman scatter rice grains across the field to warn rats not to eat them. The woman returns in the afternoon to make an offering to the spirits of the field. She bores a hole into the ground and drops a few seeds into it. Then she covers the hole with taxalitaw vine leaves and the sapitan herb. This is to ensure that the crops will be healthy. For the whole night and all throughout the next day, she cannot hand out anything to anyone, and no one is allowed to enter her house. On the third day, other women take up the chore of planting. They carry dibble sticks with which they bore holes in the ground. Coconut shells full of seeds are tied to their waists. It is taboo for children to make noises, because they would likely disturb the spirits: the paxananay, who watches over the planting, and the bibiritan, who kills people when roused to anger. In September, the rice is ready for harvesting. It is then cooked with the fire of the stored charred wood from the burned clearing; thus, the cooking of the rice completes the ritual cycle of the swidden.

|

| Ruins of Pudtol Church, 2014 (Joanner Fabregas, Wikimedia Commons) |

There are several rituals performed in connection with the harvest of rice. These usually begin with the killing of a pig as an object of sacrifice, accompanied by communication with the spirits, performed in the form of prayers by the dorarakit or the maganito (shaman). In the pisi, the ritual offering of food to the spirits, rice pudding is offered to Pilay, the spirit of the rice, who resides on the paga, a shelf above the Isneg hearth. The old woman who performs this utters the following prayer: “Ne uwamo ilay ta ubatbattugammo ya an-ana-a, umaammo ka mabtugda peyan” (Here, this is yours, Pilay, so that you feed my children fully, and make sure that they are always satisfied) (Vanoverbergh 1941, 340).

Another ritual is performed right in the fields where the harvest is going on. The amulets inapugan, takkag (a kind of fern), and herbs are tied to a stalk of palay, which are later placed in the granary before the other palay. Again, these are reserved for Pilay. In case a new granary is built and the contents of the old granary transferred, the spirit’s special share is also transferred to the new place. It is never consumed. An illness in the family during the time of harvest occasions a ritual called the pupug. The shaman catches a chicken and kills it inside the house of the affected family. The usual prayers to the guardian spirits of the fields are recited, after which the household members partake of the meat of the sacrificial animal.

Isneg House and Community

Isneg architecture differs markedly from that of the other groups in the Cordillera. The difference lies mainly in the boatlike design of the Isneg house. Apayao in the northernmost part of Luzon is the only region in the Cordillera with a navigable river, and among the mountain people of the north, only the Isneg are natural boatpeople and boat builders. A typical Isneg house resembles the traditional Isneg boat in some ways. The boat called barana’y or bank’l is made up of three planks: a bottom plank that tapers at both ends and two planks on both sides, carved and shaped in such a way as to fit alongside the bottom plank. The roof of the Isneg house suggests an inverted hull, and the floor joists when seen from the outside appear to have the shape of a boat.

|

| Isneg octagonal house built circa 1915, photographed in 1983, Butbut, Apayao (Trix Rosen) |

The Isneg house is called binuron. It is regarded as the largest and among the most substantially constructed houses in the Cordilleras. The binuron is a multifamily, one-room, rectangular dwelling supported by 15 wooden piles, with a clearance from the ground of about 1.2 meters. It measures about 8 meters long, 4 meters wide, and 5.5 meters from the ground to the roof ridge. The walls slant and taper downward. Its atap (roof) is gabled, in contrast to most Cordillera dwellings, which have pyramidal or conical roofs. A tarakip, an annexlike structure, is built at one end. It is as wide as the house itself, with a slightly higher floor but a lower roof. Some houses feature a tarakip at both ends. The Isneg use wood for the sinit (posts), anadixiyan (girders), toldog (joists), and dingding (walls); and thatch or bamboo for the roof. An interesting feature of the Isneg house is the way the bamboo roof is constructed. Lengths of bamboo tubes are split in two, and these are laid in alternating face-down-face-up arrangement, their sides interlocking. Several rows are laid on top of one another like shingles. Thus, they form a continuous wavelike link and effectively keep out rainwater. Sometimes, a layer of grass thatch is laid on top of this bamboo arrangement for added protection.

The Isneg binuron is an example of the northern style of Cordillera architecture because it is gabled, elevated, and elongated. Its floor and roof are entirely supported by two completely independent sets of posts. The floor itself has slightly raised platforms along the sides. This is the opposite of the southern house, the roof of which rests on the walls of the square cage constituting the house proper and which in turn is supported by posts that reach no higher than the floor joists.

Although the Isneg house may seem small, there is ample space inside because it has no ceiling. One looks up to see the interior side of the bamboo roof. Because the walls slant outward toward the roof, the space inside also expands. Another interesting and practical feature of the binuron is its roll-up floor made from long reeds strung or woven together. These are laid on top of a floor frame made up of lateral and longitudinal supports. Once in a while, the reed floor is rolled up for washing in the nearby river. The walls of the house are but planks fitted together, all of which can be removed so that the binuron can be converted into a platform or stage with a roof, to be used for rituals, ceremonies, and meetings. For windows, a number of wall planks are removed to provide the needed openings; thus, they are not structured frames cut out of the walls but are part of the walls themselves.

As swidden farmers, the Isneg build their family house as close as possible to their uma. Thus, when the Yapayao of Saliksik were relocated to Dumalneg, they would build sigay (makeshift shelters) on their kaingin fields to avoid making the daily, 10-kilometer trek between Dumalneg and Saliksik. When the famillies started trickling back to Saliksik after five years of residence in Dumalneg, they built only makeshift homes of bamboo and grass thatch at first. Eventually, they built sturdier family homes though still made of bamboo.

Another important architectural work in Isneg society is the alang (rice granary). Building big granaries remains an important part of Isneg material culture because in the Cordillera communities, the granary shelters not only the annual harvest of grains but also the benign spirits like the balawan (female granary spirit), which is invoked to guard the treasure of food they contain. These granaries are provided adequate protection, mainly with rat guards found on the upper part of the posts that may be disc-shaped or rounded plate, knob- or pot-shaped, or cylindrical. The contemporary Yapayao’s granary is small, about four square meters, but built more solidly than their family house. The structure is elevated three feet above the ground by posts that have a rat guard attached to each. Traditional wooden rat guards have been replaced by ones made of galvanized metal sheets. The granary is enclosed by walls of dried tree bark, and its roof is thatched with cogon grass. A shed similar to the granary stands in the middle of or beside the kaingin to serve as the farmer’s resting place. A fence of sharp, pointed bamboo stakes encloses the uma so as to keep predators like boars and monkeys away.

Rituals likewise accompany the building of houses in Apayao. From the initial act of looking for suitable wood in the forest to the final completion of the binuron, the Isneg act according to traditional beliefs. Some of the customs and practices that the Isneg follow are also faithfully observed in other Cordillera communities. The labag is a tiny red or brown bird that the Isneg observe and listen for when they are about to gather timber to build a house. If it flies across or opposite one’s path, or if it emits an extended series of chirps with pauses in between, it is a bad omen and one should postpone one’s plans for the day. If the bird flies along one’s route, or if it emits a speedy and continuous chirping, it is a good omen. A chicken’s bile sac may also be examined for signs of approval before cutting a tree down. The appearance of a rainbow, a sneeze, and a death in one’s community are signs of misfortune.

Having built the house, an owner will now host the most important ritual in Isneg life: the say-am. First, a male dancer is selected for the dance performance. Then the female shaman offers betel nuts and throws rice grains to the spirits, in an act of propitiation, in case any kind of transgression has been committed at the place where the house has been built. The ceremony also serves to call the spirits to watch over the family. At a corner of the hearth inside the house, rice is planted and covered with ash. Offerings of homemade sweets to the spirits follow.

Isneg Traditional Costume

Unlike other groups, the Isneg have no traditional or indigenous knowledge of cloth weaving or pottery making. Instead, they have procured articles of clothing, pots, and other materials from the lowland Ilocano traders, in exchange for their honey, beeswax, rope, baskets, and mats.

|

| Isneg couple in their indigenous costumes, 2014 (Roel Hoang Manipon) |

Nevertheless, Isneg women have been known to favor colorful garments for their traditional costume. These consist of both small and large aken, a wraparound piece of blue cloth with narrow red or white horizontal stripes. The small version is for everyday use, while the large one is for ceremonial occasions. The aken is usually kept in place by the bahakat. Around six feet long, this strip of cloth is wrapped around the waist over the aken and also serves as a carrier for small articles. The women also wear the badio, a short-waisted, long-sleeved blouse, which is either plain or heavily embroidered, and the laddong (head scarf). The usual colors for these articles of clothing are blue and its various shades often with narrow stripes in red and white.

Menfolk, on the other hand, have a traditional dress of dark-colored, often plain blue, G-string called abag. On special occasions, this is adorned with an iput, a lavishly colored tail attached to the back end, which generally consists of a thick tuft of long fringes. They wear an upper garment called bado, which has long sleeves and reaches down to the waist. The colors are usually grayish blue, although sometimes the Isneg also wear them in red and dark blue, occasionally in black or purple.

On festive occasions, men and women wear their distinctive costumes. The men wear their abag loincloth with decorative beads and tassels, a long-sleeved jacket—usually green, the festive color of choice, or sometimes dark blue or red—and an embroidered headpiece. The women wear long-sleeved dark blue, sometimes red or orange, jackets; striped or plain navy blue aken skirt; and embroidered headpiece. Into these turbans they may tuck pompoms or flowers for accent.

|

| Isneg elders, 2016 (facebook.com/TarakiAkTarakiKaTarakiTayoAmin) |

Among the Yapayao, the men’s baag (loincloth) is traditionally woven on a back-strap loom and dyed black or dark blue. The women’s quen (wraparound skirt) is multicolored and woven on the same loom. In 1992, the older-generation Yapayao of Saliksik were observed to still don their traditional garments for their daily wear. They also had gisi (tattoos) on their arms and necks. Presently, the Yapayao ordinarily wear the conventional clothes of the lowland people. However, they put on their traditional garments during the fiesta of Dumalneg and their community rituals.

Isneg men also sport the sipatal or sipattal, a necklace/breast piece indicating one’s social status. The sipatal, worn exclusively during special occasions, has two parts: the sipatar (necklace or collar) and the bissin (pendant). The sipatar is composed of around 14 beaded strings that are bound side by side by several strips of wood or carabao horn to produce a flat necklace. The bissin consists of several cut shells, adorned with multicolored glass, agate, or ceramic beads. Men also wear the abungot (turban), which is a long blue cloth wrapped around their head. The linijot is a ceremonial turban that comes either in plain red or in half red and half blue. This headpiece is embellished with leaves from the bangog (ylang-ylang plant), dulaw (feathers), and several saaban (string of beads).

The only decorative art that the Isneg have developed from earliest times is tattooing. There are names for the various types of tattoos. There are tattoos for men and tattoos for women. Isneg males tattoo their forearms down to the wrist and the middle part of the back of their hands. This basic type is called hisi, generally black in color and of no particular design. The andori is the more ornate type, which appears on one or both arms, on the inside. It begins from the wrist and runs all the way to the biceps and the shoulders. The design is composed of mainly wedges, diamonds, and angular lines.

The andori used to symbolize the status of an Isneg male who has killed any number of enemies. The more he killed, the longer the andori on his arms. This type is largely gone now, having been associated with the practice of head-taking. Another type is the babalakay (spider), which is tattooed in front of one or both of a man’s thighs. This is either a cross-shaped figure with twiglike extensions at the ends or several lines radiating from a small imaginary circle, suggesting an arachnid but also rather sunlike in appearance.

The women decorate themselves with one of three types of tattooing. One is the andori, which the Isneg woman is allowed to have on her arms if her father has killed any number of enemies in battle. She may have the balalakat tattoo on her throat and on either or both of her thighs, sometimes also on her forearm. Or it may be the tutungrat, a series of broken lines at the back of her hands, sometimes accompanied by some dots or short, parallel, straight lines tattooed at the back of her fingers.

|

| A sample of an Isneg sipatal (Photo by Masato Yokohama, Form and Splendor: Personal Adornment of Northern Luzon Ethnic Groups, Philippines by Roberto Maramba. The Bookmark, Inc., 1998.) |

While the Isneg do not produce much basketry, they fashion some articles of useful application, such as spearheads, tattooing instruments, axes (aliwa for the men and iko for the women), and protective rain gear. Of the last item, there are two kinds. One is the killohong, a round hat made from palm leaves, strips of rattan, or bamboo, or sometimes carved out of a dried gourd, with a head-fitting structure attached inside. Another is the ananga, a kind of raincoat made of palm leaves. This gear has a woven base which closes in around the neck, while the tops of the leaves extend all around the body like an open fan, leaving only the front of the body partially exposed to the rain. Mats are woven from anahaw or pandan palm, which is grown as a second crop for this reason.

Isneg Folk Riddles and Folktales

Isneg oral tradition is rich in folk riddles. Many of these are structurally simple but elegant: two lines with a few syllables and rhymes at the end, presenting an enigma that must be guessed. Like most folk riddles, those of the Isneg encompass practically every aspect of human experience: men, women, children, the human body, ailments and defects, actions, food and drink, dress and ornament, buildings and structures, furniture and implements, animals, plants, the natural environment, and natural phenomena. Some examples of their rhyming riddles follow (Vanoverbergh 1976; 1960):

Apel Iggat

Awan na di mamilgat.

(The thigh of Iggat,

Which all scrape at. [Honey])

Bulinawan ka Gannad

Lipuliput amlad.

(Black stone at Gannad,

surrounded by little fishes. [Mortar])

Tabiyo-o dalen silay;

Dalenko makibabbay.

(A man on the mountain

A plainly visible liver. [A bottle of coconut oil])

Tolay a bantay;

Masisilag na agtay.

(There are two canoes

Only one man rides them. [A pair of shoes])

Other Isneg riddles have been recorded only in English translation (Vanoverbergh 1976):

They are many following one another, and each one carries a nest. (Aeta)

Someone is weeding all the time without any reason. (A person rowing a boat)

One singit post for the whole town. (Mayor)

A basket full of pipes, one smells bad. (Mayor)

It dances on the floor and has no sound, it dances on the rock and resounds. (A blacksmith’s hammer)

A very large bunga tree with only two branches. (Carabao)

Half a bamboo, it can be seen from afar. (Rainbow)

A small rooster going to America and coming back the same day. (Telephone or airplane)

We cannot say it except at the time of harvest. (Riddle)

The Isneg have stories and fables that explain events and phenomena, and relationships between people and their surroundings, or which are simply meant to be humorous and entertaining.

|

| “Why Birds Steal People’s Grains” (Illustration by Dominic Agsaway) |

There is a story about why birds steal people’s grains. Long ago, a man had no grains, and he went hungry. Birds came and offered to give him seeds of rice and corn from a certain rock in a faraway place. The man was supposed to plant these then share the harvest with the birds. He agreed, whereupon the birds fetched the seeds. The man planted the seeds but reneged on his promise to share the harvest. Since that perfidy, rice birds have been attacking the rice plant and crows have been damaging the corn as a punishment for the man who broke his promise.

Another tale is set in the proverbial “time of plenty” and relates why rice grains became so small people had to work hard to harvest them. Once upon a time, when people were still kind and gentle, they enjoyed an abundance of rice, which did not need to be planted nor harvested. Innumerable giant rice grains simply appeared and rolled toward them. A woman and her daughter began building a rice granary that could hold the nonstop arrival of rice onto their doorstep. As they worked, the rice grains kept rolling toward them, until the mother angrily struck one and ordered it to stop coming where it wasn’t wanted. The grain shattered into a thousand tiny pieces, which then vowed never to go to people again. From then on, people have had to labor hard to get rice.

The Isneg explain the origin of things and natural phenomena in their stories. The sal-it (lightning) is created when the man holding the world makes fire with his flint and steel so he can light up his cigar. When this zigzag of fire hits people, it eats their brains; when it strikes trees, it eats the pests on them. The addug (thunder) is the roaring sound made by boulders in the sky when these are carried along by the flow of rainwater. The yagyag (earthquake) occurs when a giant eel and giant crab beneath the earth fight each other, and the eel’s tail hits the pillar supporting the earth.

The art of tattooing began when a tattoo-covered man taught it to Halossab in a dream. Upon waking, Halossab sold his tobacco harvest to buy ink and 15 dagum (needle), which he used to tattoo himself. His neighbors envied him for the beauty of his tattoos, and they paid Halossab a chicken each to be tattooed the same way. The Isneg’s art of tattooing explains the distinctive colors of the iguana and the crow. Iguana and Crow were good friends who agreed to tattoo each other. Crow tattooed Iguana very carefully, giving him a speckled look; but Iguana, who was lazy, merely poured black paint all over Crow.

The Isneg have their version of the “star maiden” story. Enoy has a farm planted with sugarcane and bananas. For three consecutive nights, three women visit Enoy’s farm to enjoy its produce. Enoy does not catch them until the third night, when the three women remove their clothes and wings so they can bathe. Enoy sits on the youngest woman’s clothes and wings while the other two fly away. Ayo, the youngest sister, is persuaded to live with Enoy, and they have a child together. One day while Enoy is out hunting, Ayo discovers her wings tucked in a crack in the wall of Enoy’s house. Quickly she shuts the doors and windows and flies away. When Enoy arrives, their son tells him where Ayo has gone, and Enoy, carrying his son, goes after her. The houses in Ayo’s place are made of bulawan beads. When she sees them in her house, Ayo welcomes Enoy and their son with a meal.

Sillam-ang is the Isneg parallel to the Iloco legendary hero named Lam-ang. While Sillam-ang’s mother was still pregnant with him, his father was killed in a headhunting foray. As soon as he was born, Sillam-ang could talk, while a male chick that hatched at the same time crowed. One day, Sillam-ang went in search of his father, whose dried-up head he found in an Igorot town. All the residents of the town threw their spears at him, and he caught them all with his mouth. However, with a single throw, his spear ran through all his enemies because it was being guided by a young female Aran spirit. Sillam-ang took his father’s head home and placed it in the family mortar with his rooster companion, and his father’s life was restored.

|

| Isneg folktale about Gisurab’s odd-looking rooster (Illustration by Dominic Agsaway) |

Gisurab the giant is a recurring character in a series of humorous Isneg folktales. One day, Gisurab builds a fish trap on his riverbank. Meanwhile, on another side of the river, Agippagippaw takes a dainty bite from a bunanag fruit, but she loses it and it gets caught in Gisurab’s trap. Taking his rooster with him, Gisurab goes in search of the owner of the fruit. His rooster leads him toward the side of the river inhabited by people. They laugh at the one-feathered, one-winged, one-eyed, one-legged, and one-beaked rooster. It sees their large teeth and knows the owner of the bunanag fruit is not among them. It arrives at another village where the women are pounding rice. They, too, laugh at the rooster, which again notices their big teeth. Finally, it lands on the riverbank where Agippagippaw lives. She smiles at the rooster. It sees her dainty teeth and goes to tell Gisurab that it has finally found the owner of the bunanag fruit. Gisurab invites Agippagippaw to go with him and he makes a raft on which he places all her hogs, dogs, and chickens. They sail toward the crocodile den, where Gisurab takes the hogs under the water. Here, he and the crocodiles eat the hogs. They do the same with the dogs. Finally, while he is under the water with the chickens, Agippagippaw calls on her brother Dalawiggan, who is sitting atop a rock, to put down his ladder. She climbs to the top of the rock. Gisurab now wants to eat her, so he calls on his friends the crocodiles to lie one on top of the other so he can reach Agippagippaw. But as he steps on the crocodiles, they fall down, and they have to do it all over again and again. A variation to the ending of this story goes thus: When the woman realizes what Gisurab is up to, she prays and a ladder appears. She climbs the ladder and ascends to the sky, where Gisurab cannot reach Maria.

Another recurring character in the Isneg folktales is Ipngaw, the trickster. In one tale, Gisurab leaves a jar full of bananas, which Ipngaw tries to steal, but his hand gets stuck in the jar. Gisurab comes, and Ipngaw pretends to be dead, so Gisurab throws him away. Ipngaw flees, with Gisurab in pursuit. Taking a stump, Ipngaw enters Gisurab’s nose, where he smokes the stump. With Gisurab in pain, Ipngaw escapes once again. Another version of this tale has Ipngaw eating Gisurab’s basketful of bananas and replacing them with rocks. The deception gives Ipngaw ample time to escape.

Isneg Songs

Some Isneg possess skills in traditional oral arts, such as the magpayaw (shouters), the singers of the oggayam or ugayam and other songs,and the debaters who joust with anenas (oral poetry). There are others held in esteem as musicians, such as those who display prowess in playing the difficult gorabil (bamboo violin).

|

| Isneg ritual, 2015 (April Rafales) |

Music plays an important part in social intercourse. Once a young man has decided on who to court, he starts wooing with his baling (nose flute) or his orbao (mouth harp). Or he might sing to her a dissodi (courting song). On solemn occasions such as burials, feasting precedes the actual rites. The food is provided by the dead person’s relatives. During this feast, gongs are beaten, and the community participates in dancing and the drinking of basi.

|

| Isneg women performing planting dance, 2015 (April Rafales) |

Isneg songs, called buybuyas, may be classified into five types, according to their naral (tune) and the occasion in which they are performed: dewas, salen dumay, ugayam, adu-duit, and ag-axi. The dewas and the salen dumay songs are performed in chorus during the say-am. What distinguishes the salen dumay from the dewas is that the former is sung at a higher pitch, and the boys and girls alternate in the singing of the verses and the refrain.

The Isneg have different terms for the same types of songs, depending on which district of the province they come from. The ugayam or inannas are non-occasional songs and can thus be sung anytime. Mamabay, literally “to court the girls,” is a courtship or love song. The inannas, from the root word nannas, meaning “girl,” may also be a courting song. The ag-axi, from axi, meaning “speech,” is a way of talking that is set to a tune. A mamabay, or parts of it, may be sung like an ag-axi. The adu-duit, also called maxapatpatan, meaning “to talk, to chatter,” dandannay, or palpaliwa, are ballads or narrative songs with rhymed verses, and are sung for pastime by anyone of any age, the elderly and children alike.

A man named Uwil from the village of Bolo, Kalinga-Apayao, provides the following sample of a dewas (Vanoverbergh 1960):

Salsalí-dummây dummáãy

Salsalí-dumdúm dumewas

No maweyã-ka Banag

Panalá-nã-ka bakará

Panamdammanko kenká

To-tó-tuganto-tuwé tuwé tuweto-to-tó

Sallen dumay dumáay

ippayko ya paniyóo

Taximmatóñko kiyá ilalbétmo

Oxoogâyam oxogãyáman

No ináto-yo ímao

Paninna(n)mo kiyó runátko

No ibabá-yo imao

Paninná(n)mo kiyó napiyá na uräy-o

No mawêka kanná Aparri

Pangátannã-takoli

Panamdammãnko kiyá piya urây mo

Asín suká gattín lãyá

Umadãyyókãyo na burowa

Bantayka siwayanan

Pagdardarnan a lalpaan

Nalimat mariya nagbatta

Kalimutta nebutta

Sina-paw awitta

Ka ambaw waxa

Ta-banda-man ka da-nag

O bilele bilele innas ayus idummo dewas simbam

balolo genas

Maglibakayo wala

Nam uray mape nala

Oxoggayam ogayaman

Maweya pekanna balay

Sinnanko pe silalay

Oogayam ogayaman ogayam ogayaman

Magpatuliya no iddem

Ya taxematon naya bulan

Oogayam ogayaman

Oxoogayam oxogayaman

Oka bawan palali mud-udi mon-onna

No maweka kanna bolowan

Pangatanna ka bulawan

Panamdammanko kenka.

(Salsalí-dummây dummáãy

Salsalí-dumdúm dumewas

When I go to the Ibanag

Get me a bakara headband

For my remembrance of you

To-tó-tuganto-tuwé tuwé tuweto-to-tó

Sallen dumay dumáay

When I apply my handkerchief

It is my sign for your coming

Oxoogâyam oxogãyáman

If I raise my hand

It shows you my anger

If I lower my hand

It shows you my good mind

When you go to Aparri

Buy me a canoe

For my remembrance of your good mind

Salt vinegar iron ginger

Go away Buroa [a half-bird half-man being]

You are a mountain covered with taro

A heap of vegetables

Was drowned Mary crossing the water

Turning (among the waves) thrown away (with the

boat)

Caught her at Awitta

Below the Waga River

Cover me please with dry leaves

O bilele bilele innas ayus idummo dewas simbam

balolo genas

You feign your love all the time

But never mind

Oxoggayam ogayaman

I go to my house

I see silalay plants

Oogayam ogayaman ogayam ogayaman

I shall come back if you give

If you tell me in what month

Oogayam ogayaman

Oxoogayam oxogayaman

Oka garlic the last comes first

When you go to Boloan

Buy me bulawan beads

For my remembrance of you.)

Video: Talip Folk Dance [Carasi (Isnag) Indigenous Cultural Dance]

There are two general types of dance among the Isneg: the taduk and the talip .In both dances, the girls and the boys have specific roles to play. Generally, only unmarried girls take part in dancing. The same three or four girls take turns, repeatedly. On the other hand, most of the boys and men, married as well as unmarried, are expected to join the circle. Those who display skill, especially in the fast-beat talip, win the applause of the crowd.

There are other specialized dances for festive occasions. Balengente is a festival dance that starts with a brave warrior shouting and performing movements that dramatize his successful head-taking foray. The villagers follow him and join in the feasting as the warrior dances with the head of his enemy.

There are many variations of the courtship dance. In one version, a ceremonial blanket is flapped by the female like the wings of a bird in flight. The man’s movements, on the other hand, resemble those of a fighting cock springing into the air. The pingpingaw (swallow) imitates the movements of this swift bird, again with the use of colorful blankets. Turayan (flying bird) is a dance similar to the Bontoc version of the same name. In this, three dancers, two women and a man, imitate the movements of the turayan as it flies, glides, and swoops. The dancers move about with their arms outstretched, simulating birds in flight.

Media Arts

The film Ang Probinsyano (The Man from the Province), 1996, opens with the scenic view of the mountains and rivers of Santa Marcela, Apayao. The film is the story of Lieutenant Kardo de Leon (Fernando Poe Jr.), Santa Marcela’s chief of police and town hero, known for his courage and honor. In one scene, despite operating beyond his area of jurisdiction, he single-handedly wipes out a band of goons in order to recover a revered image of the Santo Niño that has been stolen from a barrio. He is then reassigned to Manila to help bring down a highly influential drug syndicate. Successful in his mission, the provincial cop returns to his previous job at Santa Marcela.

Sources

Alfonso, Amelia B., Leda L. Layo, and Rodolfo A. Bulatao. 1980. “Culture and Fertility: The Case of the Philippines.” Research Notes and Discussion Paper No. 20, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Beyer, H. Otley. 1918. “The Non-Christian People of the Philippines.” In Census of the Philippine Islands 2, 907-957. Manila: Bureau of Printing.

Casal, Gabriel. 1986. Kayamanan: Ma’i—Panoramas of Philippine Primeval. Manila: Central Bank of the Philippines and Ayala Museum.

Cole, Fay Cooper. 1909. “Distribution of the Non-Christian Tribes of Northwestern Luzon.” American Anthropologist 11 (3): 329-347.

Eugenio, Daminia L., ed.1989. Philippine Folk Literature: The Folktales.Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Folklorists Inc.

“False Dawn for Filipino Tribals.” 1987. Survival International News 18: 2-3.

Guardia, Mike. 2010. American Guerrilla: The Forgotten Heroics of Russell W. Volckmann. Philadelphia: Casemate Publishers.

Keesing, Felix M., and Marie Keesing. 1934. Taming Philippine Headhunters; A Study of Government and of Cultural Change in Northern Luzon. California: Stanford University Press.

———. 1962. “The Isneg: Shifting Cultivators of the Northern Philippines.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 18 (1): 1-19.

Maramba, Roberto. 1998. Form and Splendor: Personal Adornment of Northern Luzon Ethnic Groups, Philippines. Makati City: The Bookmark, Inc.

National Statistics Office. 2002. “Apayao: Three Out of Five Academic Degree Holders Were Females.” Philippine Statistics Authority. http://web0.psa.gov.ph/content/.

Norling, Bernard. 1999. The Intrepid Guerrillas of North Luzon. Kentucky: The University Press of Kentucky.

Peralta, Jesus T. 1988. “Briefs on the Major Ethnic Categories.” In Workshop Papers on Philippine Ethnolinguistic Groups. International Festival and Conference on Indigenous and Traditional Cultures, Manila, 22-27 November.

Perez , Rodrigo, III, Rosario Encarnacion, and Julian Dacanay Jr. 1989. Folk Architecture. Photographs by Joseph R. Fortin and John K. Chua. Quezon City: GCF Books.

Philippine Daily Inquirer. “Killings Tarnishing Image of Apayao as a Peaceful Province.” 2013. Inquirer.net, 26 July. http://newsinfo.inquirer.net/453329/.

Regional Map of the Philippines-II. 1988. Manila: Edmundo R. Abigan Jr.

Reid, Lawrence A. 1994. “Terms for Rice Agriculture and Terrace Building in Some Cordilleran Languages of the Philippines.” In Austronesia Terminologies: Continuity and Change, edited by Andrew Pawley and Malcolm D. Ross, 363-388. Canberra: Australian National University Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies.

Reyes, Ronwaldo, director. 1996. Ang Probinsyano. FPJ Productions. DVD, 117 minutes.

Reynolds, Hubert, and Fern Babcock Grant, eds. 1973. The Isneg of the Northern Philippines: A Study of Trends of Change and Development. Dumaguete City: Anthropology Museum, Silliman University.

Salvador-Amores, Analyn V. 2013. Tapping Ink, Tattooing Identities. Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

Scott, William Henry. 1958. “A Preliminary Report on Upland Rice in Northern Luzon.” Southwestern Journal of Anthropology 14 (1): 87-105.

———. 1962. “Cordillera Architecture of Northern Luzon.” Folklore Studies 21: 186-220.

———. 1969.On the Cordillera. Manila: MCS Enterprises.

———. 1975. History on the Cordillera: Collected Writings On Mountain Province History. Baguio City: Baguio Printing & Publishing Co., Inc.

Smart, John E. 1971. “The Conjugal Pair: A Pivotal Focus for the Description of Karagawan Isneg Social Organization.” PhD dissertation, University of Western Australia.

———. 1993. “The Flight from Agiwan: A Case Study in the Socio-Cultural Dynamics of an Isneg Marriage Negotiation.” Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society 21 (4): 330-343.

Valdez, Roseanna. 1982. “The Bontoc Fayu and the Isneg Binuron: A Cross-Cultural Comparison of Two Examples of Philippine Vernacular Architecture.” MA thesis, University of the Philippines.

Vanoverbergh, Morice. 1929. “Dress and Adornment in the Mountain Province of Luzon, Philippine Islands.” Catholic Anthropologist Conference 1 (5): 181-244.

———. 1932. “The Isneg.” Catholic Anthropologist Conference 4 (1).

———. 1936. “The Isneg Lifecycle: I. Birth, Education and Daily Routine.” Catholic Anthropological Conference Publications 3 (2): 81-186.

———. 1938. “The Isneg Lifecycle: II. Marriage, Health and Burial.” Catholic Anthropological Conference Publications 3 (3): 187-280.

———. 1941. “The Isneg Farmer.” Catholic Anthropologist Conference 3 (4): 281-386.

———. 1953. “Isneg Riddles.” Folklore Studies 12: 1-95.

———. 1955a. “Religion and Magic smong the Isneg Part 2: The Shaman.” Anthropos 48 (3-4): 557-568.

———. 1955b. “Isneg Tales.” Folklore Studies 14: 1-148.

———. 1960. “Isneg Songs.” Anthropos 55 (3-4): 463-504.

———. 1972. Isneg-English Vocabulary. Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii.

———. 1976. “Isneg and Kankanay Riddles Explained.” Asian Folklore Studies 35 (1): 37-166.

Wallace, Ben J. 2006. The Changing Village Environment in Southeast Asia: Applied Anthropology and Environmental Reclamation in the Northern Philippines. London and New York: Routledge.

———. 2015. “Advocacy in Anthropology: Certificates of Stewardship for the Yapayao of Northern Luzon.” Philippine Studies Journal. www.philippinestudies.net/files/journals/1/.../3028-3522-1-RV.doc.

Wilson, Laurence L. 1967. Apayao Life and Legends. Quezon City: Bookman.

Worcester, Dean C. 1906. “The Non-Christian Tribes of Northern Luzon.” Philippine Journal of Science 1 (8): 791-875.

———. 1912. “Head-hunters of Northern Luzon. (Covers Negritos, Ilongots, Kalingas and Ifugaos).” National Geographic Magazine 23 (9): 833-930.

This article is from the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Digital Edition.

Title: Isneg

Author/s: Edgardo B. Maranan, with additional notes from E. Arsenio Manuel (1994) / Updated by Rosario Cruz-Lucero, and Gonzalo A. Campoamor II (2018)

URL: https://epa.culturalcenter.gov.ph/1/2/2351/

Publication Date: November 18, 2020

Access Date: September 05, 2022

![Isneg The Isneg (Isnag) Tribe of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Cordillera Apayao Province Indigenous People | Ethnic Group]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEigCL3HzfumVdLV5MCTlK1QLZNTKoDbKMiuMq9zAHi04YibCgEjffkijkzg_er2z35wB6sOCfEeTKFxo5BMCXFCcN0RsApI-Ke6QcXMnn4o_CwUD5Gv1jP0JNgilVLqnwq5udvsCOXkQtb14fxUZ-P9bp2MVfBbbp20gHqDTvdIC7MBn1QgUQ/s16000-rw/Island%20Escape.png)

No comments:

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?