The Kankanaey People of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Indigenous People | Cordillera Ethnic Tribes]

Kankanaey, also Kankanay, Kankanai, and Kankana-i, refers to the culture and the people who primarily reside in Benguet and Mountain Province of the Cordillera Administrative Region. The terms have no definite etymological derivation.

|

| Kankanaey village by the terraces (SIL International) |

As of 2002, the total population of the Kankanaey is 321,329, concentrated in two provinces: Benguet and Mountain Province. In Benguet, there are 142,000 or 43% of the province’s total population; in Mountain Province, 72,694 or 52% of its population. The Kankanaey are also dispersed in small percentages all over the Philippine archipelago. In the Cordillera region, there are 971 of them in Apayao; 28,963 in Baguio; 970 in Ifugao; and 4,350 in Kalinga. In the Ilocos provinces, there are 1,724 in Ilocos Norte and 17,232 in Ilocos Sur. In Central Luzon, there are 4,980 Kakanaey in Nueva Ecija; 18,645 in San Fernando City in La Union; and 3,206 in Tarlac. They are in southern Luzon, too, where there are 282 in Lucena City, Quezon province. In the Bicol region, there are 2,291 Kakanaey in Aurora; 953 in Camarines Norte; and 1,429 in Sorsogon. In the Visayas region, there are 1,752 of them in Leyte; 1,264 in Aklan; 3,040 in Iloilo; 5,150 in Negros Occidental; 2,241 in Negros Oriental; 46 in Siquijor; 216 in Biliran; 836 in Bohol; and 5,384 in Cebu. The Kankanaey are also in Mindanao, 710 of them being in Lanao del Norte.

The Kankanaey have their own language called Mankayan, which is closely related to the languages of the lfugao and the Bontok, two groups with which the Kankanaey share geographical borders. Bakun-Kibungan, Guinzadan, Kapangan, and Mankayan-Buguias are classified as dialects of the Kankanaey language.

There are two Kankanaey groups: the northern Kankanaey, also called Lepanto Igorot, and the southern Kankanaey. Most of the northern Kankanaey are located in the southwestern part of Mountain Province and inhabit the municipalities of Besao, Sagada, Tadian, Bauko, and Sabangan. The southern Kankanaey are found in the municipalities of Mankayan, Bakun, Kibungan, Buguias, and the upper half of Kapangan in Benguet. The Kankanaey in Benguet may also be called Benguet Kankanaey to distinguish them from the Benguet Ibaloy, who inhabit the lower half and the most urbanized parts of the province, including the vegetable-growing valley of La Trinidad and the melting-pot city of Baguio.

The northern and southern Kankanaey are physically and culturally alike, with similar institutions, beliefs, and practices. However, the more ancient northern Kankanaey were called Lepanto Igorot by the Spanish colonizers. This refers to an administration area whose boundaries have changed through successive colonial regimes but was known as the missing center of the Cordillera. The southern Kankanaey appear to be an expansion of the northern Kankanaey group. The settlements in the south seem to belong to the historic period, as evidenced by the small acreage built for rice terrace culture.

History of the Kankanaey People

Both northern and southern Kankanaey have always been rice terrace agriculturists. The original 34 villages of the northern Kankanaey, located on high slopes of the central Cordillera range, are concentrated near the Kayan-Bauko and Sumadel-Besao areas. These communities appear to have existed long before the coming of the Spaniards to the archipelago. Proof is the extensiveness of their rice terraces, which must have taken a considerable period to build. The fact that these terraces and the names of the first communities were noted in the records of the first Spanish expedition to the Cordilleras in 1665 is a confirmation of early Kankanaey civilization. Moreover, the Benguet area had some of the largest gold and ore deposits, and the Kankanaey and Ibaloy who had settled here had been panning and digging for gold long before the Spaniards arrived on the islands.

|

| Kankanaey woman with freshly harvested rice stalks (Photo courtesy of Cesar Hernando) |

Several reasons have been advanced for the division of the Kankanaey into two. One reason is that the group that went up to the hills could not afford to have another group control the source of water after they were driven away from the coastal belt. Another reason proposed is that the salutary climate of the Cordillera highlands, with its lush green vegetation and other natural riches, may have attracted the ancestors of the present mountain dwellers to go beyond the “malaria-ridden jungle belt” that stops at the 1,000-meter line of the mountains. The northern Kankanaey occupy a region that averages 2,000 meters above sea level. They may have arrived at their present location due to the process of displacement; or they may have naturally gravitated to a terrain more to their liking or to one that is similar to southern China, which, according to a theory of migration, their ancestors have left behind. The forebears of the northern Kankanaey started building rice terraces near the villages.

Because the foothills and coastal plains of the Ilocos region lie across the boundary to the west, the Kankanaey areas are contiguous to the lowlands. This made them more susceptible than the Bontok, Ifugao, and other mountain people to external influence, though less vulnerable than the Tinguian and the Ibaloy who were even nearer and more accessible to both the Spanish colonial forces and the Filipino lowlanders and settlers. The Spaniards had occupied the adjacent lowlands as early as 1572, but it was only after a hundred years that they were able to reach the territory of the northern Kankanaey.

The Spaniards went up the Cordillera in search of the fabled gold. In May 1572, Juan de Salcedo, grandson of Governor-General Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, led an expedition, which yielded 25 kilograms of gold three months later. This, along with other reports of Cordillera chiefs and their slaves possessing gold, encouraged subsequent expeditions such as those led by Francisco de Sande in 1576, Juan Pacheco Maldonado in 1580, Luis Perez Dasmariñas in 1591, Francisco de Mendoza in 1591, and Pedro Sid in 1591. However, most of the gold gathered by the Spaniards did not come from mining but from either the collection of it as tribute or the looting of the gold and heirlooms from the Cordillera people. The people themselves stopped mining and kept the location of their gold mines a secret. A series of more expeditions were led by Pangasinan Governor Captain Garcia Aldana y Cabrera in 1620, Sergeant Major Antonio Carreño in 1623, and Governor Alonso Fajardo in 1624. The futility of their search led to the Royal Audiencia’s decision to discontinue all subsequent expeditions.

The Spanish colonizers left the area, unable to maintain their outposts, and for almost 150 years, the northern Kankanaey were left in peace; what contact there was between the people of the highlands and the lowlands was indirect. The Spaniards came back in the first part of the 19th century, and established a comandancia de Lepanto (Lepanto military district) in 1852, measuring 2,167 square kilometers, bounded by Abra and Bontoc on the north, Benguet and Nueva Viscaya on the south, Bontoc and Kiangan (Quiangan) on the east, and Tiagan and Amburayan on the west. The comandancia de Lepanto was composed of five towns and 40 villages, with Cervantes and Mankayan as principal towns. The Kankanaey, referred to by outsiders and the Benguet-Lepanto Igorot as the busao (enemies) in the area, put up some resistance.

Spanish control, wielded through the force of arms and proselytization, eventually set in. Mankayan’s copper mines were opened to exploitation by a Spanish mining company. People in some districts were compelled by the Spanish authorities to grow coffee and tobacco for the colonial government. Missions and schools were put up in certain areas.

The homeland of the northern Kankanaey saw access roads from the Ilocos coastal region built to reach it, and these new routes facilitated the influx of Spaniards, Filipino lowlanders, and Chinese traders. The opening of the western flank of the Cordillera set into motion acculturative processes that would have a great impact on succeeding historical periods. These processes would include Christianization, urbanization, political modernization, and integration of a highland agricultural society to a market economy.

The eruption of war between Spanish and American forces and the subsequent war of independence waged by Filipino revolutionaries against the new colonial forces drew the involvement of the Igorot people. While the nation was undergoing the throes of a full-blown national war, age-old conflicts over the use of resources and cultural differences between the Kankanaey and their traditional rivals were revived. A resurgence of headhunting occurred for some time until pacification set in under the new American regime in 1902.

In 1899, the US army pursued the revolutionary leader, Emilio Aguinaldo, in the Cordilleras. Some of the former American soldiers returned to the mountains in search of the gold they had heard so much about. Early reports by American officials about the abundance of gold, particularly in the Itogon area, contributed to the influx of former soldiers-turned-prospectors. Knowing little, if at all, about prospecting, they succeeded in finding the gold either by befriending the “Igorot” or by marrying into kadangyan or baknang (traditional aristocrat) families who already had control of the gold mines.

The Americans established a local government and several regulatory agencies in order to secure its interests in the mineral-rich Cordilleras and to stop the growing number of miners from usurping higher authorities. The Mining Bureau oversaw all mining activities, and the Bureau of Public Lands facilitated mining grants and claims. Laws that were instituted paved the way for Americans to claim the lands that once were owned, operated, and developed by the local population. Almost half of the 88 sections of the Philippine Bill of 1902, or the Organic Act, pertained to mining. The construction of an important road, known later as Kennon Road, made Benguet and other gold-rich areas accessible to Manila and the lowlands. As a result, the total gold production of the country reached almost half a million pesos per year between 1907 and 1911, around half of which was from Benguet alone. By 1929, Benguet was yielding 86% of the total 6.7 million peso gold production and 92% of the 73.7 million pesos just before World War II. Much of the increase in yield was attributed to the continuously high production and the discovery of new mining sites, most notably in Itogon and Balatoc.

In 1904, the Kankanaey, particularly those from the town of Suyoc in northern Benguet, were among the indigenous peoples of the Philippines brought to the St. Louis World’s Fair, in Louisana, USA, to showcase what the United States called its “possessions.” Together with 70 Bontok and 17 Tinguian, the 25 Kankanaey composed the “Igorrote Village” at the Exposition. Among them was the Kankanaey Dang-usan, who was married to Charles Pettit, an American soldier turned gold prospector in 1900 during the Philippine-American War. Pettit’s fellow prospector was another war veteran, Truman Hunt, who became Bontoc’s lieutenant-governor and was tasked to put together the “Igorrotes” for the Fair. Persuaded by Dang-usan and Pettit, the former’s relatives and neighbors joined the other “Igorrotes” and arrived at the fairgrounds on 25 March 2004. An 18-year-old Kankanaey woman died of pneumonia a month after their arrival. Referred to in the fair as “Suyocs” and “miners,” the 25 Kankanaey—fourteen men, seven women, and four boys, with ages ranging from 6 to 50—demonstrated their skills in blacksmithing, metalworking (i.e., making tininggal or copper chains), fabric- and basket-weaving, pipe-making (making pek or pipe), beadwork, mining, and copper and ore reduction. The four boys attended a “model school” with the Bontok children. After eight months, they left the United States on 13 November with a group of Visayans and Tinguian.

In the Philippines, the Kankanaey, Bontok, Ifugao, and other Cordillera groups were integrated under the new politico-military dispensation. Protestantism, military service, and education created a new Igorot identity for the Kankanaey and the other Cordillera people, especially those who comprised the new educated elite.

Japanese forces during World War II penetrated through the Mountain Province in February 1942. In need of much needed resources, the imperial forces headed straight to the province’s copper mines, including those in Mankayan. Daily production in the Lepanto copper mine in Mankayan, which operated until the end of the war, reached 1,000 tons.

Soon after the ouster of Marcos in 1986, the new president Corazon Aquino signed a peace pact with the Cordillera People’s Liberation Army (CPLA), an armed group that aimed for regional autonomy founded on the institutionalization of the bodong or peace pact. Negotiations between the government and the CPLA led to the formation of the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) in July 1987. CAR also reunited the former mountain provinces, including Abra as a special region. But the Organic Acts enacted by Congress that would have transformed Cordillera into an autonomous region were rejected in the January 1990 and March 1998 plebiscites.

Kankanaey Way of Life

Gold mines have always been known to exist in the Cordilleras and were the primary reason why the Spanish colonizers attempted to conquer it. Gold mining, particularly in the Benguet area, determined Kankanaey life in a very basic way. The Kankanaey gold miners traded with the lowlanders for Ilocano blankets, Pangasinan salt, and livestock, as well as for prestige items like Chinese porcelain jars, beads, cattle, pigs, and other livestock to be slaughtered for their extravagant feasts. In 1630, Spanish conquistador Juan de Medina included in a list of goods acquired by the highlanders an “abnormally large and completely white swine” (as cited in Habana 2000, 461).

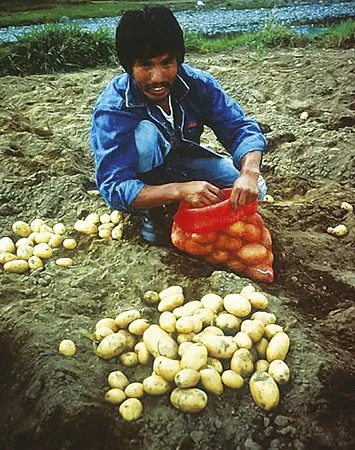

|

| Vegetable farmer with his harvest of cabbages and potatoes (SIL International) |

The Kankanaey predominantly occupied Mankayan and thus had a monopoly of its copper and gold deposits. On the other hand, the Kankanaey and Ibaloy shared the mineral deposits of Suyoc, Tabio, Acupan and Antamok. Pansejew (gold panning) was done by the women along the Agno, Bued, Suyoc, and Ammburayan Rivers, with the use of a sadjewan, a rectangular pan that strains the water to separate the gold dust. The earliest recorded reference to gold panning by the Kankanaey was in 1545, when oral history mentioned a girl named Damya who “used to wash gold at Labang” (Habana 2000, 462).

Gold buried in hard rock in Antamok, Acupan, and Balatoc, all in the Itogon area, were extracted through open pit mining called labon (tunnel mining) as far back as hundreds of years ago. With the most primitive equipment, the Kankanaey miners dug deep into the mountains, broke rocks by heating then dashing cold water onto them, and carried the ore outside where they milled it.

|

| Vegetable farmer with her harvest of cabbages and potatoes (SIL International) |

Aside from gold mining and trading, agriculture also determined the Kankanaey’s choice of their settlement sites. The Kankanaey practice three types of agriculture: swidden or slash-and-burn, terracing for wet rice production, and horticulture. Close to their dwellings, the Kankanaey maintain little orchards that supply fruit for their consumption as well as vegetable gardens and sweet potato patches. Sugarcane and tobacco used to be cultivated for domestic consumption but with the shift to cash economy, most fields are now planted with fruits and vegetables for commercial sale. More affluent Kankanaey farmers use motorized farm implements, but the carabao-drawn plow is still used by others, and manual labor is employed in building and repairing the terraces, planting, weeding, and harvesting the rice and vegetable fields.

Agriculture is a year-round activity. In Bagnen, Bauko, Mt Province, the phases of agricultural cycle are the sama or sowing of seeds, starting in August; toned or transplanting in December; kames or weeding and putting up a kilkilaw (scarecrow), starting February of the next year; lugam or cleaning of the kabiti (stone wall), starting in April; and latab or harvesting, starting in June.

Older generations of Kankanaey used to hunt deer and wild boar in forests, and catch eels and crabs in rivers. The supply of meat is supplemented with chickens and pigs. Chickens are also sold for needed cash. The Kankanaey, however, do not raise poultry on a large scale. Other domesticated animals are dogs, carabaos, goats, and cattle. The carabao, although the principal work animal, is occasionally slaughtered for extravagant family and community feasts.

The Kankanaey who live near streams or close to the water-filled rice terraces catch fish, which is not common fare in the mountains where the diet usually consists of rice, vegetables, and meat. Hand nets, poison, hook-and-line, or stream draining during the dry season are the methods used by the Kankanaey for fishing. Hunting and fishing have been severely affected because of the continuing denudation of the once vast timberlands of the Cordillera forests.

There are part-time or seasonal occupations for carpenters, who receive wages for work done. Pottery has been known for a long time, but recently, potters have been losing their livelihood or have seen it decline sharply because of the introduction of modern kitchenware from the lowlands. Other traditional crafts include blacksmithing, basketry, and weaving. Rattan, which used to grow in abundance in forests surrounding Kankanaey villages, is still available and provides the basket makers one of two primary materials—the other being bamboo—for executing intricate, creative, and meticulous designs on their baskets. Weaving, which is still done with the blackstrap loom, has produced cloth that is not only used for domestic purposes but is also well received in the market. The usual Kankanaey woven cloth is narrow, about 4.5 meters wide and 2.1 meters long. This is either sold or bartered to other neighboring groups.

With the integration of Kankanaey society into the cash economy, and with the attractiveness of earning more cash in urbanized places, a significant number, many still in their teens, have sought to find employment in Baguio City and elsewhere. Their earnings are either spent for education or sent home to support family members for the purchase of household items such as metal tools, kitchenware, cloth, hats, sugar, and salt.

Tribal Life of the Kankanaey People

In the past, when there were bigger Kankanaey settlements, the at-ato existed as a focal point of communal unity. The at-ato was a meeting place where village elders would gather. It used to be located right in the middle of a settlement. The term is related to the Bontok ato, designating the place where elders gather to discuss community matters. The Kankanaey version was on a smaller scale, but its functions were possibly similar. The loss or abandonment of the at-ato can explain in part the dispersed small settlements that are now features of the cultural landscape. The fact also that headhunting, one of the major decision-making concerns in the council of elders, has entirely disappeared from Kankanaey practice may serve to explain the disappearance of the at-ato. Above all, the institution of municipalities as political subunits of provincial governments has almost completely relegated the at-ato to history.

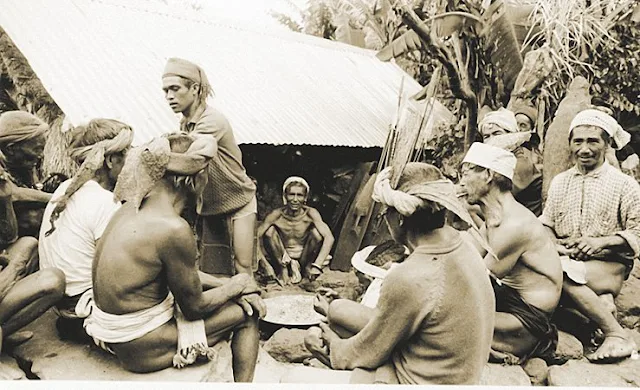

|

| An informal gathering of Kankanaey men to discuss community matters (SIL International) |

The at-ato, as it flourished in northern Kankanaey society, was a subvillage grouping that mediated between the village unit and the house unit. Dap-ay was also a name used to refer to it. The Spaniards, who exercised colonial control over local institutions, were aware of the basic function of this “village section” and therefore called it tribunal. The at-ato in the past was headed by a war leader, and it also had a priest. But the group itself was composed of the village menfolk, particularly the warriors who engaged in armed battles against other groups and took heads as trophies. These heads were deposited in the at-ato, where the ceremonial cañao or kanyaw (feast) was held after each successful engagement with the enemy.

There is no formal political leadership in Kankanaey society, except that which is acknowledged by virtue of an individual’s social class, knowledge of oral tradition, possession of healing powers, knowledge of agricultural rituals, and the venerable wisdom that comes with age. Formal political leadership is a modern-day phenomenon, and it comes in the form of bureaucratic placement in the national-local government system.

The kadangyan or baknang (the traditional aristocracy) wielded the biggest influence in their society. During the Spanish colonial period, they were recruited as district presidente or village konsehal and, upon retirement, earned the title kapitan. During the American occupation, they were the primary choice, as the local elite, for filling up high positions in the colonial bureaucracy.

The manabig (wise old men) were “keepers of the lore and traditions” and were expected to “define correct custom, interpret procedure in cañaos, remember significant matters from the past.” Since a manabig was called upon to solve personal and communal problems, he was accorded deep respect, and his services were compensated with meat, rice wine, or both.

The manpudpud (wise old women) specialized in curing illness and were gifted with the ability to talk to the spirits. They were consulted by families and individuals for the diagnosis and treatment of any kind of illness for which was prescribed the proper cure and the appropriate cañao ceremonies. In a way, leadership was exercised by the manpudpud because they directed the actions of people and mandated the proper social activities to be undertaken so that social harmony could be restored through the banishment of illness.

The mamade or mamadur (agricultural shamans) presided over the elaborate rituals in connection with the seasonal rice crop. This leader—and each village had one—was keeper of the agricultural calendar and master of ceremonies in community and at-ato observances. The mamade might decide to seek the counsel of the manabig in making certain decisions.

The manapat (wise elder),also called lakay (a word borrowed from the Ilocano), was part of a cluster of informal political leaders, collectively called lalakay, who formed the nucleus of the community councils, supervised litigation, became witness to special negotiations such as property settlements, and assisted in the affairs of the village, the at-ato, and kin groupings. The lalakay’s word carried weight in community life, although not all elderly persons in a village could be acknowledged as a respected elderly person. In a village, there could be ten such people, whose qualifications were advanced age, some amount of wealth, and past sponsorship of the bayas ceremony, which was a type of cañao.

The at-ato and the informal leadership of the above-mentioned elements of northern Kankanaey society have been transformed or muted by the assimilation of this group into a centralized national society. The transformation, nevertheless, has not completely wiped out these institutions. Thus, contemporary leaders may still invoke respect for the at-ato and the social/spiritual elite who used to provide counsel in daily life.

Kankanaey Culture, Traditions, Customs and Social Organization

Video: The Kankana-ey IP Group

The basic social unit of the Kankanaey is the family, which consists of the husband, wife, and their young children. Marriage is monogamous and generally permanent when the couple has children, and the family bears a complex set of responsibilities related to economic and ritual activities. The nuclear family may also include older but unmarried children; aged parents who are too old to look after themselves or their own separated household, or who have become widowed; and close relatives who cannot fend for themselves due to indigence or who have been left alone due to death or divorce. However, though they do partake of the family meals and engage in all the family activities such as chores and religious practices, they are free to come and go as they please, and can opt to sleep elsewhere if they wish.

|

| Kankanaey mother and child (SIL International) |

A Kankanaey individual may belong to two groups of people, the sinpangapo or sinpangabong and the sin-aag-i. The sinpangapo are blood relatives, that is, they can trace their kinship to a common ancestor. Individuals belonging to different clans may become affiliated by marriage, for instance, to become part of a sin-aag-i, literally “people with their relatives” (Allen 1978, 76).

The traditional village meeting center was the at-ato, a social institution meant for older boys and unmarried males. They also used the at-ato as their sleeping quarters. Unmarried women, both adults and young girls who had reached the age of puberty, slept in a designated dormitory. This sleeping place might be a house not being used by a regular household. Otherwise, it was a separate place built exclusively for this purpose. This house was called an ebgan. Independence from the household was the normal course of a young boy or girl who had reached a certain age. Association or bonding with other adolescents prepared them for a new phase of relationships that would eventually lead to marriage.

Two main approaches to marriage are customary: parental arrangement, which is the old tradition, and courtship, which has increasingly gained favor among the new generation. In either case, parents of both parties participate in the process. The old tradition has not been inflexible. An individual’s choice of his or her marriage partner is not subject to disapproval from the parents, who recognize the right of daughter or son to make a choice. Even under the old system of parental arrangement, the Kankanaey rarely enter into a parental agreement when the children are still below the age at which they can make their own choices. Even in cases where such an agreement comes into force, this is resorted to mainly to preserve the wealth of the two families. But this parental arrangement can be set aside anytime by the children when they come of age.

The girls who stayed at the ebgan were visited by their suitors who lived in their own dormitory. Like the young men and women of Bontok and Ifugao society, premarital relations among the Kankanaey of marrying age were consummated only with the consent of the girl. After a certain period of acquaintanceship and even of intimacy, the couple might decide to get married. The young man then informed the woman’s parents about their decision. Kankanaey custom required that he render service at the girl’s house for a week or a month. Should he merit the final approval of the girl’s parents through his conduct, and if the omens proved to be good, the wedding was set for solemnization at the girl’s house. There were intermediaries employed to make the nuptial arrangements, particularly in the wedding and ritual expenses, which entailed a number of animal offerings such as carabaos, pigs, and chickens, a huge reserve of rice, and tapuy or tapey (rice wine). Bride-price, which used to be a primary consideration in Kankanaey marriages, is no longer as important today. In the past, this consisted of animals, precious heirloom beads, blankets, woven cloth, rice, and other valuables, the quantity depending on the wealth of the boy’s family or the demands of the girl’s family. The present practice is for both sides to contribute to the food to be consumed.

The newlyweds may reside with the bride’s family while they are constructing their own house, or until such time that an unused house can be provided for them. Other couples, especially those employed in urban areas or abroad, immediately live on their own after their wedding ceremonies in their hometown. Those who remain in their hometown with their parents help out with work in the house, the yard, and the field as they prepare themselves for an independent life later. The parents may decide to allot a piece of land for them to cultivate and to enable them to live apart.

Mutual respect is observed by husband and wife, although decision making in most matters is patricentric. Traditionally, the man is expected to provide all the needs of the family, but women are increasingly contributing to the family finances through employment either in their hometowns or elsewhere. In the fields, the man takes charge of clearing the land, but weeding and harvesting require the spouses’ cooperative effort. House-building is entirely a man’s work, but he gets assistance from kin or neighbors. The wife prepares the meals while the construction is in progress.

If the pregnant wife decides to abide by the traditional manner of childbirth, the husband stays under the house, prepared for any eventuality, while his wife is being assisted upstairs. In Bagnen, a newborn is called amenga if a boy and amenaket if a girl. In child rearing, the man participates almost equally with the woman, often carrying the child in a sling on his back while at work in the yard or in the field. When one of them dies, the surviving spouse’s married offspring, with his or her own children, may join her in the household, or she joins a married offspring’s family.

There is social stratification in Kankanaey society. The kadangyan occupy the topmost rank as hereditary “aristocrats” by virtue of their landholdings, capacity to conduct ritual activities, and other evidence of material wealth. During the precolonial up to the early 1900s, the kadangyan status among the Benguet Kankanaey was primarily based on ownership or control of gold mines. Through gold trade, the kadangyan expanded their land, increased their wealth, and wielded influence on the lower classes. This practically extended their authority to the political, economic, social, and religious aspects of society. However, this authority was lost when many kadangyan-held lands were declared public property and large American companies staked their claim and took over the mines in the early decades of the 20th century. During this American takeover of gold mines, most of the laborers and miners in Mankayan would be transferred to Tuding and Balicno.

In 1909, Jose Fianza, on behalf of his family and kin, filed a case against John F. Reavis, who in 1901 claimed the Antamok and Ampasit mines and sold them to Benguet Consolidated. These lands had long before been mined by Jose’s father Dominguez and grandfather Toctoc. The case, which had dragged on until just before Jose died, was resolved when he received a jarful of palata (coins) as payment for the properties. The disputed land would later on become the Benguet Mining Company (Habana 2001).

At the bottom of the social scale are the kodo (the poor), who are individuals or families who do not own rice lands or other possessions of measurable value. They make do with whatever inferior food they can avail for themselves or earn their keep by working for others or, as in the case of the Benguet Kankanaey, engage in mine-related activities. The kodo are individuals who have descended from lineages which have been, for generations, impoverished and working in servitude. At the middle of these two extremes is an intermediate class of independent property holders called komidwa (second rank). Even within the kadangyan class, however, there are gradations of prestige and status, depending on the degree of relationship to the main “aristocratic lines” (Keesing 1968, 29). The members of the two higher-ranked classes may not have their fortunes intact all the time, as when they go into land mortgages or when a series of unfavorable omens may require them to host prolonged, expensive ritual sacrifices.

In hosting their extravagant festivities, the kadangyan are not only propitiating the spirits to keep them healthy and wealthy but are also giving themselves an opportunity to share their blessings with the less-advantaged Kankanaey in the community. Thus, in asking for more, they wish to be able to share more.

Since marriages have always tended to take place within socially homogenous circles, class distinctions have been stabilized over time. However, contemporary Kankanaey society, as elsewhere throughout the Cordillera region, has been undergoing processes of political, economic, social, and cultural change. These processes actually began with Spanish colonial exactions before the 20th century, as well as with the introduction of new diseases and epidemics, hence requiring frequent propitiatory ritual sacrifices, which drained the old kadangyan’s economic resources. Afterward, the American colonial administration saw the rise of a new political and economic elite, with new sources of power and prestige, even as old ones were closed. War and headhunting exploits, from which the elite drew prestige and status, ceased to be normal activities a long time ago. Furthermore, a socioeconomic class that can be described as “newly rich” has entered the picture. They include the mixed-blood descendants of Ilocano and Chinese traders who traveled to the Cordilleras, set up their businesses, usually trading and vegetable farming, and intermarried. And finally, elite recruitment into the modern political system has been possible even among nontraditional elite classes, as a result of educational attainment, experience in electoral politics, and wealth acquired through business and professional practice.

The kadangyan, nevertheless, have remained leading figures in Kankanaey society. The aristocratic lineage of the kadangyan is traced, through oral tradition, to the very figure of Lumawig, the cultural hero of many Igorot groups who they honor through the bayas, which was a type of cañao that validated the kadangyan’s stature. In the past, social homogeneity in the kadangyan class was made possible by marriages within the class and between kadangyan from different villages. There has been greater upward—as well as downward—mobility in Kankanaey society. Some of those who have managed to retain their traditional upper-class standing may still be practicing the duties of the classic kadangyan, although in altered forms. These duties include maintaining and enhancing the status of the family name by successful management of the inherited and acquired property, making the fields and the livestock productive, overseeing the work and securing the welfare of dependents, preparing to host a bayas feast by saving up their resources, and conserving these traditions for the sake of the next generation.

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Kankanaey People

The supernatural world of the Kankanaey is replete with male and female god figures, as well as spirit-beings who comprise a hierarchy of deities under one supreme entity called Kabunian, creator of all beings and living things in the world. Kabunian is mainly responsible for the welfare and general well-being of all those he created. He is also looked upon as the supreme master who taught humans everything they need to know for life, such as making fire, the cultivation of rice, and marriage rituals. Desirous of a peaceful and bountiful life, the Kankanaey utter the words “Itunin sang kabunayen” (Thank you, Kabunian) at every fortuitous turn of events (Demetrio et al. 1991, 14-15).

|

| Kankanaey begnas, Sagada, Mountain Province (Jennifer Sy Carag) |

Next to Kabunian is a descending order of lesser gods and spirits. The male gods are Lumawig, Kabigat, Suyan, Okalan, and Balitok. The female gods are Moan, Daongen, Angtan, Bangan, Gatan, and Oboy. Their names are recited and invoked by the Kankanaey in various rituals so that they may intercede for people and facilitate the granting of favors needed or desired.

Part of Kankanaey cosmology is the story of how the spirits dwelling on earth actually came from the descendants of two mortal beings, Lumawig and Bangan, the first creatures on earth. They were the survivors of a great deluge that occurred thousands of years ago which was caused by Kabunian, who commanded the waters of the seas to rise until all the existing land was inundated. The only place untouched was a mountaintop where Lumawig and Bangan had sought refuge. After the flood subsided, Kabunian ordered the two to become husband and wife so that the earth could be populated again. But Lumawig and Bangan refused because they were brother and sister. They would only do so, they said, if the Supreme Being could make them laugh, and thus the two siblings were tricked into marrying each other. Lumawig and Bangan had four children in all. One was given the task of performing the cañao. This child’s descendants became the Igorot. The second was assigned to weave abel (cloth) and became the ancestor of the Ilocano. The third was given the power of issuing commands, and his descendants became known as the Merkanos. The fourth child was destined to become a spirit who would inhabit stones and trees, and became the ancestor of the malevolent spirits who we know today as the tumungaw or mangmangkik.

The tumungaw or mangmangkik cause various illnesses and are also responsible for typhoons, epidemics, and other calamities. But there are four spirits who are feared the most: Insaking, Buduan, Kise-an, and Putitik. They inhabit the big heart-shaped stone on the mountain of Tenglawan. When displeased, these spirits cause stomach aches in human beings. Other minor gods and the ailments they bring include liblibayan, spirits who cause pains in the abdomen; an-antipakao, spirits who create reddish spots all over the body; penten, spirits who cause accidental death; and kakading, souls of the dead who cause colds, headaches, or fever. The liblibayan and an-antipakao spirits live in sitios where there are people, while the penten inhabit rivers, springs, and other water bodies. These spirits react angrily whenever people trespass on their territory. The malevolent spirits are believed to be under the sway of a still more powerful and cruel being known as Mantis Bilig—the god of death and destruction. On the other side, there are benevolent spirits called kading and pinad-ing, invisible spirits usually in human form who protect people from typhoons, misfortune, and epidemics. For the southern Kankanaey, the pinading are the mountain spirits; the bilig are the field and forest spirits; and the dagas are the house spirits.

These deities and spirit-beings are invoked by the Kankanaey in their rites and rituals related to life, livelihood, and death. Most, if not all, of the rites and rituals are performed by the mambunong or manbunong, who reads from the bile sac or liver of a sacrificial animal the sentiments or attitudes of the spirits toward the propitiating or transgressing human being. There are also female mediums called mangengey. Both manbunong and mangengey inherit their religious position from parents who were themselves spiritual leaders. Another hereditary position is that of the mamade or mamadur, who can be replaced if the rituals he performs fail to produce the good harvest prayed for by the community. Another religious position is that of the balsun, who may be called upon to perform rituals for a specific occasion or purpose, in which he is recognized to be most knowledgeable.

|

| Kankanaey ceremonial container (CCP Collections) |

The Kankanaey practice a great variety of rites and ceremonies. Several types of economic activities, such as planting, harvesting, house building, or digging irrigation ditches, call for the performance of these rites. A whole village or a family financially capable of throwing a feast takes responsibility for the holding of big and elaborate rites. For determining the cause of illness or divination of events, simpler rites are performed by an individual or by a family group.

One of the ritual ceremonies already mentioned is the bayas. This cañao or feast, the most important festival in northern Kankanaey society, is hosted by the kadangyan and involves the slaughter of many animals. Only a person of means can afford the amount of food consumed. During the bayas, the kadangyan appeals to his ancestral spirits for their continued support for his prosperity. Here is one such batbat (prayer) that the manbunong addresses to their hero gods (Moss 1920, 357):

Lumawig un Kabigat, si Pati, si Soyaan, si Amdoyan, si Wigan, si Bintauan, si Bangan, si Bogan, si Obongan, si Obung, si Laongan, si Singan, si Maodi, si Kolan, si Moan, si Angtan, si Gatan, si Angban, si Mantalau, si Balitok; minyaan midakayos, yan tagoundakami. Idauwatmoi masangbo, tamo matagokami pangiyaan di ibamin dakami; tamo dakayo ay kabunian waday pangiyaan min dakayo; tamo anakmi waday matago ya waday pangiyaan min daka yo.

Mopakenmi adadoenyo, tauaday piditenmi. Mo manokmi abu, matago tauwaday panbiagmi. Mo mansamakmi, abu, mataguay; batong mataguay, din togi mataguay; ta waday panbiagmi. Mo mansamakmi, abu, si pina, ya kapi adadoi bagasna, ta waday ilaukami, ta waday iami sigalimi.

(Lumawig and Kabigat, Pati, Soyaan, Amdoyan, Wigan, Bintauan, Bangan, Bogan,Obongan, Obung, Laongan, Singan, Maodi, Kolan, Moan, Angtan, Gatan, Angban, Mantalau, Balitok; we are giving this to you that we may live long. Work for us to become rich so that while we live there will be the giving of meat to us by our companions; so that you the gods will have things given to you; so that our children will have life; so that there will be gifts for you.

What we feed increase, so that there will be celebrations of ceremonies again. Cause our chickens also to live to be for keeping us alive. Make what we plant also to live; beans to live; camotes to live; to be for keeping us alive. Make what we plant, also, pineapples and coffee, to have much fruit, so that we may have it to sell, that we may have something with which to buy blankets.)

Relatives, villagers, and visitors from other places are all invited to the bayas ritual. During times of plenty, the bayas would be celebrated at least every three or four years, but in recent years the interval has become longer.

The rites observed in connection with the agricultural cycle are deemed indispensable because the whole success of planting and harvesting, that is, survival itself, may depend entirely on such observance.

Manteneng is a ritual that begins the planting phase. Here, the owner of the rice field plants the first two or three rice seedlings and recites a prayer asking the spirits of the field to help the plant grow tall. Only after this will the other workers begin the planting of the rest of the seedlings.

Legleg is performed to improve the growth of the plants. This is done whenever the bonabon seedlings show telltale signs of withering. A chicken is killed, and is offered to the spirits of the field, trees, rocks, and other things in the surroundings believed to have been angered or displeased. Four or five long feathers of the chicken are pulled out and stuck into the site where the bonabon are planted. If the seedlings do not show any sign of improvement, the ritual is repeated, this time with more sacrificial chickens.

Harvest entails a different set of rituals. On the first day, the rice fields are declared off-limits to strangers. Along trails, crossed bamboo sticks called puwat are laid out as a warning to passersby against intruding. The owner of the field cuts a handful of rice stalks and recites a prayer asking for a bountiful crop. Then, the other reapers proceed to cut the rest of the harvest. Nobody is allowed to leave at anytime throughout the day, to prevent “loss of luck.”

The opening of a baeg (granary) by a family for rice pounding is an event with its own ritual. The head of the household declares an abayas (holiday), which lasts two days. The father opens the granary, and takes out as many bundles as required for the period of celebration.

The largest and most important of community celebrations among the Kankanaey is the pakde or begnas. This is observed for a variety of purpose. When called to ensure an abundant rice harvest, it takes place sometime during May, a month before the actual harvest. It may also be observed when a person dies to ask for the protection and favors of the benevolent deities. The village elders may decide to hold the rites after the observance of a bagat (big feast) by a family to regain luck for the community. Or the occasion might be to celebrate a strange event such as lightning striking a tree near a house or near a spot where people have assembled, which is interpreted as Kabunian himself speaking. A pakde or begnas serves to appease him. This usually takes place during the rainy season, when lightning is most frequent. The celebration is held for one day and one night with preparations of food, water, and tapuy. On the day of the feast, men with bolo and spears come out of their houses and proceed to the village borders, to put up barricades across all entrances. Others take up their spears and accompany the manbunong to a sacred spot where there is a wooden structure called pakedlan. On this a pig is butchered and offered to the guardian deities of the village. The pakedlan is usually built by the manbunong at one end of the village. It consists of a solitary wooden post about 1.3 meters in height, with large white stones laid on the ground surrounding it.

Simpler rites, mainly for the purpose of divining the causes of illness, are also observed. Disease is attributed to the workings of malevolent spirits or angered deities. The anap, literally, “to find out,” are divinatory rites performed by a man-anap (medicine man or woman). These are of various types: Baknao, in which the diviner makes use of a coconut shell filled with water. The shell is covered, and a prayer is recited over it. The diviner removes the cover and tries to read in the water the name of the spirit or deity that has caused the disease. Buyun, in which a stone, a string, and a bracelet are used by the diviner, who ties one end of the string to the bracelet and the other end to the stone. While holding up the stone, he or she calls out the names of various spirits. The spirit who causes the dangling stone to move is deemed the cause of the illness. Sip-ok, in which the diviner takes a bottle upside down, and puts budbud (yeast) on its bottom. Praying over it, he implores Kabunian to help reveal the cause of sickness and the type of sacrifice required to cure it. The diviners are called manbaknao, manbuyun, or mansip-ok, depending on the particular medium or method used during the ritual.

These divinatory rites are then followed by a sacrificial feast called an-anito or mansenga, which is similar to the legleg, except that it is performed to seek intercession for an ailing person. Animals are butchered and offered to the spirits believed to be the causes of ailments.

Traditional Kankanaey Houses and Village

Traditionally, the Kankanaey village was set on the hump of a hill whose elevation afforded a natural defensive advantage against neighboring groups. Today, Kankanaey villages are located near the headwaters of a stream or river since irrigation water is needed for the rice terraces. A typical village of the northern Kankanaey or Lepanto Igorot would have at least 700 inhabitants, occupying a cluster of some 150 houses. Slopes of hills or mountains are leveled to allow the houses to be built. Near this village is a sacred grove of trees used as a place for ritual sacrifices or performances. The village also includes the rice terraces whose walls serve as pathways; a nearby peak that serves as a “sacred mountain”; certain places on the outskirts where omen reading and other rituals may be observed; and burial places along the cliffs and slopes.

|

| Typical Kankanaey dwelling made of bamboo and nipa (SIL International) |

There are three main house types: the binangiyan, the apa or inapa, and the allao. The first type is generally for the prosperous members of the community, while the apa and the allao are for the less well-off. The binangiyan, which is similar to the Ifugao house, has a high-hipped roof, with the ridge parallel to the front. Its roof drops down to about 1.5 meters from the ground, thus covering the house cage from view. The house itself rests upon a structure consisting of three joists on two girders on four posts. Close to the ground is a wooden platform stretching out to the eaves. This is made of several broad planks laid together above the ground, instead of stone blocks set on the earth. This space is used for weaving and cooking. Stone is used as pavement around the house. The interior consists of a sleeping area, a kitchen with a hearth in one corner, and storage space for utensils. The space formed by the roof and the walls becomes useful for storage.

The floor, which is about 1.5 meters above the ground, is not enclosed, enabling members of the household to do chores such as weaving, making baskets, and splitting wood. There is an opening to one side leading to a narrow passageway that is protected by a sliding door. A pigpen may be found in one of the end corners. The living room is upstairs, which is also the sleeping and dining area. The attic space formed by the high roof is used to store rice. There are no windows, except for a small opening in the roof serving as a smoke vent. The low eaves afford protection against heavy rains. The house has only one entrance, the front door, accessed through a slender detachable ladder. Vertical flutings decorate the door panels, while horizontal wavelike flutings are a feature of the beams and joists. There are no disc-shaped rat guards under the girders of the house.

The apa and the allao, which are dwellings for the less prosperous Kankanaey, are built more simply than the binangiyan. Like the poor Ifugao’s abode, the apa has walls which are perpendicular to the ground, with the four main posts as corners. The material used for the floor is split bamboo and lengths of runo. Although the roof is conical as in the binangiyan, it is lower and closer to the ground. The allao, on the other hand, has a rectangular floor. Its gable-shaped roof slopes down beyond the floor towards the ground, and thus the simple structure has no need for walls.

Changes in Kankanaey architecture were brought about by contact with the outside. Apart from the binangiyan, apa, and allao, there is the inalteb, which is not indigenous but rather similar to a house in the lowlands. It has a gable-shaped roof, short eaves, and one or two windows. There is also, increasingly, the modern bungalow type of mixed materials, as well as the tinabla, a combination of the inalteb and other modern designs.

The binangiyan is the durable example of a functional, all-purpose, practical indigenous dwelling, with plenty of living and storage space, sufficient protection against the rain, and insulation against the cold. For further warmth and comfort, the Kankanaey family keeps a fire burning in an elevated hearth located on one side of the main interior.

Kankanaey Costume and Traditional Attire

The traditional garment for the Kankanaey male is the wanes (G-string). Among the northern Kankanaey, this is usually red with colored borders or sometimes dark blue with red stripes and decorated ends. The bandala, worn by the men, is a dark blue blanket with white lines.

|

| Kankanaey textile (SIL International) |

The bak-ut, also called getap and tapis, is the female’s wraparound skirt. In other areas, the Kankanaey call this garment gaboy and palingay. The Kankanaey’s skirt reaches only down to the knee and is thus shorter than that of the Benguet Ibaloy. The everyday getap is white with indigo-blue bands. A variant of the getap called kinteg is indigo black, with white-and-blue bands. The getap is kept in place with a inandolo, also called wakes and bakget, a belt 7.5 to 15 centimeters wide, made of tightly woven cotton yarn and wound twice around the waist.

The aklang is the woman’s cotton blouse: white, short sleeved, and collarless, open in front but buttoned up at the upper end. The galey or ules is a blanket worn on the upper body as a protection against the cold. The blanket incorporates red-and-blue panels of varying widths, with mortars, snakes, or some anthropomorphic figures.

Kankanaey Traditional Weaving, Ornamentation and Body Tatooing

Traditional weaving called impaot, impagod, or pinnagod, meaning “strapped,” is done by women when they are finished with farming. Each end of the threads is tied to a tree or a house post while the other end is tied to a wood bar strapped around the waist of the weaver, who becomes part of the loom by pulling the threads back and forth with her waist, thus constantly applying tension to the threads. Threads of different colors are woven into the base threads to add patterns and other colors.

Common fabric designs among the northern Kankanaey are the tiktiko, matmata, sopo, and kulibangbang. The tiktiko are either zigzag patterns representing mountains and forests, or crisscross patterns depicting rice mortars. The matmata are diamond shapes within larger diamond shapes and resemble either rice grains or eyes. Flora and fauna are represented by the sopo, which resemble flowers, and the kulibangbang, which resembles butterflies. The woven material comes in long, narrow pieces that are sewn together, the number of seams dependent on the purpose for which it would be used. The color of this material may be blue and white or red, with dark blue designs and red-and-yellow stripes.

The men’s headcloth is called the badbad or bedbed, made of either abel or kuba (bark). Feathers, leaves, and even carabao horns may be used to decorate this head cloth. The women’s necklaces are adorned with various kinds of stones and beads. Women’s accessories are collars made of brass or matted rattan; stone and seed bracelets; earrings of copper wire; and head decorations made of beads, beans, and grass. C-shaped earrings are for both male and female Kankanaey.

The other ornamentation known to the Kankanaey is body tattooing. The tattoo art of central Benguet comes in exquisite patterns of curved and straight lines, with designs executed in indigo blue. The tattoo is pricked on the breasts and arms of men and women. The Kankanaey use a small piece of wood they call gisi, to which are attached three iron points. The same method of tattooing employed by the Ibaloy is used by the Kankanaey, which means adorning the arms from above the elbow down to the knuckles with elaborate, extensive tattoos made up of crisscross, horizontal, vertical, and curvilinear patterns. Among the menfolk, tattoos have become more and more scarce. It is the women who have kept up this customary adornment, often sporting the tattoo on their forearms.

|

| Kankanaey woven product: storage basket (CCP Collections) |

|

| Kankanaey woven product: bowl with cover made of buri (CCP Collections) |

Apart from cloth weaving with the backstrap loom, the Kankanaey engage in the crafting of baskets out of rattan and bamboo whose sizes and shapes vary according to use. They also produce wooden bowls, shields, and vases with covers that are usually carved with human or lizard figures on top, on the sides, or underneath.

|

| Kankanaey woven product: pasiking (CCP Collections) |

A Kankanaey mestizo who has distinguished himself for his fine art photography is Eduardo Masferré, 1909-1995, born of a Spanish soldier and a Kankanaey named Cunyap, later christened Mercedes Pins. His life as an art photographer began in 1933, when he got hold of a Kodak camera. Masferre’s black-and-white photographs, produced in print and postcards, were taken from 1934 to 1956. They portray people in the context of their Cordilleran lives: a Gaddang man garbed in traditional garments and warrior’s paraphernalia; a very wrinkled, old potter and her grandchild; women engaged in the various phases of rice-farming: planting, harvesting, or winnowing; cigar-smoking children and pipe-smoking adults; an overview of a farmer plodding in knee-high water in a rice paddy and pulling behind him four carabaos abreast of one another; intricately detailed tattoos on men and women; and, in a postmodern metacommentary, three men of different tribes—Butbut, Tinglayan, Kalinga—taking a close look at a camera.

Masferré’s photographs were not widely noticed until 1982, when they were put on exhibit in Manila and thereafter toured around several cities in the country, later in the Cultural Center of the Philippines, and then in several countries abroad. Original prints of his photographs are in the Bontoc Museum, National Museum of the Philippines, Smithsonian Institute in the United States, and the National Gallery of Australia.

Literary Arts of the Kankanaey People: Riddles and Folktales

The Kankanaey have a rich collection of riddles that cover a wide range of topics: people, the human body, ailments, actions, food and drink, dress and adornment, buildings and structures, animals, plants, and natural phenomena. Most Kankanaey riddles consist of two parts or statements, both with assonantal rhyme. Here are three examples:

Wad-an esay lakey

Mangguyguyud si uey.

(There is an old man

Who’s dragging rattan. [A rat])

Pising ed Kamaligan adi kasabaligan.

(A taro at Kamaligan cannot be moistened by rain.

[The eye])

Tain Balteng adi kakkeng.

(Balteng’s excrement the nail cannot dent. [A stone])

The telling and retelling of the origin of human beings and spirit-beings, as well as of the natural world, form the colorful body of oral tradition handed down through generations of Kankanaey. The myth of the origin of things and the way by which the external world is perceived and treated are tightly bound with the worship of the god Kabunian.

The Kankanaey do not have long, protracted epics on the scale of the Ifugao Hudhud and the Kalinga Ullalim. What the Kankanaey do have are the sudsud, short tales which are recounted in gatherings of adults, or when they are working in the fields during harvest time, doing work at home or around the house yard, or even when just relaxing in their leisure time. There are sudsud for children, told to them by elders for their amusement. Such stories would be less serious in tone and in subject than the stories told among adults. Some stories are actually songs, such as the day-eng, which are chanted by men and women, old and young, rich and poor, alone or in groups, day or night, at work or at play, in praise of a hero or to rock a child to sleep. The chanting is a drawling, rather monotonous tune, with words which either have no meaning at all or whose meaning has been obscured by the passage of time, and yet are understood in their entirety because the themes are well known from past and continuing retelling.

The day-eng are what could be considered the equivalent of legends and fables. The themes of the day-eng would either be tragic, heroic, or comic. There are often human characters in these stories, just as there are animals given human attributes and undergoing the same gamut of experiences as their human counterparts. While the sudsud and the day-eng may be about some legendary heroes and characters in Kankanaey folklore, they do not form a part of religious rites. Instead, another story form which recounts the adventures of spirits is narrated at public and private sacrificial rituals. These stories are called kapia (prayer).

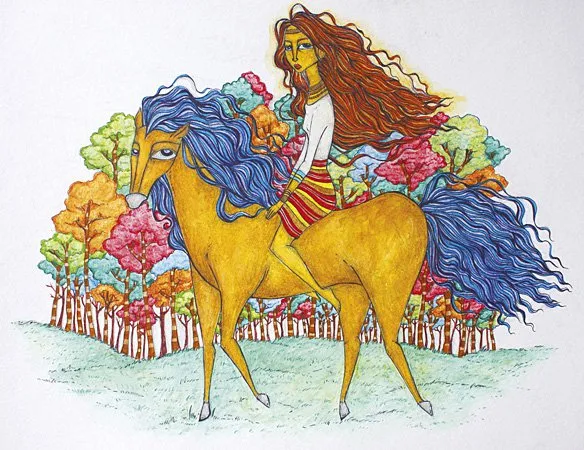

|

| Bangan, the opulent and powerful heroine of Kankanaey tales (Illustration by Luis Chua) |

In Kankanaey tales, the most recurring characters are Gatan, Bangan, Lawigan, and Bugan. Gatan is a mythological hero who is always successful in his undertakings and enjoys the protection of Kabunian. He has the magical power to work wonders, and exhibits truly suprahuman qualities common in mythic god-hero characters. It is said, for instance, that vegetation breaks into flames at Gatan’s approach. Bangan is the female counterpart of Gatan, frequently depicted as opulent and powerful, possessing objects made entirely of gold, and physically so constituted that her delicateness “melts in the sun.” She is sometimes described as riding a horse or laid out on a hammock or personifying the rainbow in the sweep of her beauty and grandeur. Lawigan is the most popular and persistent of the mythic names. Many tales give him a leading role, although sometimes he assumes a subordinate position as the son, younger brother, cousin, or neighbor of the leading hero, or his, and other alter egos. Bugan is often associated with Lawigan as his female counterpart, although she first appears in the cosmology as the sister-wife of Lumawig—probably a variant of Lawigan. From their union came the first people of the earth.

The themes of Kankanaey tales appear to be the following: marriage and family life, social customs and traditions, religious values, beliefs and practices, and tales of magic and imagination.

Here is a short tale of how the thunder and the lightning came to be: Long ago, Lumawig came down to earth and married a girl who had many sisters. Jealous, the sisters put garlic under the couple’s bed. Lumawig was displeased and decided to return to the sky, taking with him half of his offspring’s body that included the head and leaving the other half with his wife. The head complained very loudly at being without its body, so Lumawig gave it a body and a pair of legs. This head became the thunder. Lumawig then made a head for the lower half of his child’s body. This creature married the thunder, and it became the lightning.

There is also a tale that speaks of the origin of the human race: First, the gods made two people out of earth. They wanted to put life into these pair by making them laugh. So they made a chicken jump by pulling out its feathers. This made one of the two people laugh. It became a man. The other person, hearing the man’s laugh, also laughed. It became a woman.

|

| Annusan Lumawig and Bangan performing a wedding dance, as an enraged Delnagen is about to attack them (Illustration by Luis Chua) |

On 28 December 1989, a farmer and respected elder, Lakay Arsenio Ligud, was recorded as he sang “Da Delnagen Ken Annusan Lumawig,” a 446-line ballad in an Ilocano-Kankanaey language called Bago. The site of the performance was Barangay Amilongan in the municipality of Alilem, Ilocos Sur. This barangay is a mountain village near the municipality of Bakun in the province of Benguet. It is geographically nearer the Cordillera Kankanaey than the Ilocano. Until January 1990, when a road was built, one could only reach it by crossing Bakun River on foot.

The ballad’s leading characters are popular hero deities about whom numerous tales and ballads have been recited and sung. To summarize: The lovely Bangan lived in the land of the sunset. The mountain farmer Delnagen courted her, but Bangan politely rejected him. When Annusan Lumawig of the land of the sunrise came courting, she fell in love with him. To avoid hurting Delnagen, Annusan used his magic powers so Bangan would die temporarily and he could take her spirit and keep it in a bamboo tube. Then, when she was in the coffin and floating on the river, he revived her by blowing back life into her. He took her to his home in the land of the sunrise, where they planned their wedding. They invited everyone on both sides, including Delnagen. Annusan turned trees into pigs and boulders into carabaos for the wedding feast, a grand and prolonged cañao. But as Annusan was performing the wedding dance, an enraged Delnagen came and attacked him. Annusan could stop him only by splitting his magic cane into many pieces, which proceeded to beat him up. In pain and defeat, Delnagen returned home. Days later, after Annusan had finished his work on his farm, he worried about Delnagen and paid him a visit. Sure enough, Delnagen had wasted away. Annusan revived him with a sponge bath, a massage, and a prayer. Delnagen recovered and the two men were reconciled.

Kankanaey Songs

The musical instruments of the Kankanaey are identical with those used by other Cordillera groups, such as the gangsa (flat brass gongs), diwdiw-as (pan pipe), bunkaka or bilbil (bamboo buzzer), sulibaw (hollow wooden drum, used also by the Ibaloy), afiw (bamboo mouth harp), and several flute types. The gangsa is played solo or in an ensemble, particularly by men performing a dance. The other instruments are played either to accompany songs or as a means of entertaining people.

Kankanaey songs contain not only rhythm and rhyme but also poetic expressions and terms that are not used in ordinary speech. Aside from the day-eng that contain Kankanaey fables and legends, there are day-eng sung at anytime that consist of dialogues between men and women, as well as day-eng cradle songs sung by Kankanaey mothers as they put their babies to sleep.

The daing are songs that are performed during a solemn sacrifice. They consist of an exchange between a man and a woman, or between a group of men and a group of women. One side repeats the last part of its counterpart’s words to begin their reply. The other side does the same thing, and so on, creating a dialogue in the form of a cycle. The two types of daing are the dayyakus, which is used during the sacrificial rituals performed by a headhunter; and the ayugga, whose tempo is much quicker than that of the ordinary daing.

The daday are songs that are sung at the outskirts of the village. The song is a dialogue between the women of the village and a girl, an outsider, who has come to marry a boy from the village. The song ends with the triumphant entry of the girl into the village, having already been accepted by the women.

“Swinging” songs are rather short and are sung by men or women. Some swinging songs are in the form of a dialogue or verbal and vocal contests between a girl who sits upon a swing and a young man who stands nearby. If the girl loses her momentum in the dialogue, she also loses the contest and must accept the boy’s proposal. The girl usually agrees to the contest because she already likes the boy. The girls are considered better practitioners of this musical art than the boys.

There are two kinds of mourning songs: soso, which are used on the occasion of a person’s death or burial, and the dasay, sung when a person is about to breathe his last.

The bindian or bendean is a combined victory or war dance and a festive dance in thanksgiving for good fortune, such as a bountiful harvest. The hand movements are poised downward, suggesting the people’s close affinity to the earth. The basic dance step consists of the stomping of the left foot. The instrumentalists beat their gangsa as they lead the dancers in varied formations. Among the southern Benguet Igorot, this festival is called chungas. The Lepanto Igorot perform this dance primarily during the harvest season.

Foreign country music melodies have been adapted for Kankanaey lyrics that may or may not have anything to do with the original. “Batawa” (Front Yard), a well-known song by Juanito Cadangen, uses the melody of John Denver’s “Walk in the Rain” to illustrate the unrequited love caused by differences in social status. “Talaw” (Star) is the most popular song of Sendong, a Kankanaey musician from Bakun. Its lyrics are set to the melody of Brian White’s “Someone Else’s Star.”

Joel Tingbaoen, Lourdes Gomeyac-Fangki, and Brian Aliping are popular Kankanaey singers whose appeal can be attributed to their use of Ilocano and Cordillera languages and their often-local themes.

Music videos have been made available on DVDs and YouTube. Some of the producers of such music videos are Kankanaey overseas workers in Japan, whose songs speak of longing for home and the challenges of employment abroad. Most of the Kankanaey songs produced were country music songs, until recently when younger generation Kankanaey musicians began producing Kankanaey rock songs. These rock songs mix indigenous Kankanaey music traditions, such as the day-eng, and indigenous Kankanaey musical instruments, such as the gangsa, with classic rock elements and instruments. These songs are about contemporary conditions, such as the isolation of Kankanaey youth who grow up in urban centers away from their parents’ community and culture.

Kankanaey Tribal Dances and Rituals

Video: Pakan Ritual - Kankana-ey ICCs/IPs of Bagulin, La Union

Tamong is a dance meant to expedite the healing of the sick. Tayaw is another dance performed for the same purpose, accompanied by the offering of sacrificial pigs to Kabunian. Tapey is served to the dancers, who perform in big circles, shuffling, sliding, and hopping. The elders and other venerable members of the village display their priceless heirloom blankets during this occasion.

Tarektek (woodpecker) is a courtship dance that imitates the movements of the bird, with a blanket as prop. To the rhythmic beat of the gangsa, two male dancers exhibit their prowess in dancing to attract the attention of the female dancer. One male dancer uses the blanket and the other plays the gangsa, as both turn and twist around, coordinating their movements with the object of pursuit.

Aside from mimetic dances, another form of proto-drama are the rituals where the shaman assumes the role of a spirit or a god. The Kankanaey perform a ritual to effect the return of a soul which has “wandered off” on account of sickness. There are two phases in this ritual: the padpad and the paypay. Padpad is the wrenching away of a sick person’s soul from the clutches of a spirit; paypay is a search for the whereabouts of the wandering soul. In padpad, the female shaman enters into a trance, makes movements as if conversing and bargaining with a spirit, and attempts to recover it for the patient. The sickness in the body of a person is usually related to an analogous sickness of a character in a myth. A specific god is consulted about the nature and cure of the particular sickness. In paypay, the shaman clutches a chicken under her arm, and holds a winnowing basket in one hand and a stick in the other. Armed thus, she goes from place to place, even entering other people’s houses, as she tries to look for the sick person’s wayward soul. As the shaman goes about her search, she recites a prayer in Kankanaey, which translates into English thus: Paypay, let us go home to the village, it is a warm place to dwell in; confound this spirit’s house where you are dwelling, our house in the village is better, it is a warm place to dwell in.

Kankanaey in Media Arts

In Philippine cinema, commercial feature films that go as far back as the 1950s have included images of the Igorot in movies like Ifugao, 1954; Igorota (Igorot Woman), 1968; Mumbaki, 1996; Ngayong Nandito Ka Na (Now that You Are Here); 2004, and Don’t Give Up On Us, 2005. However, these mainstream films have only perpetuated stereotypes of Igorot communities, including the Kankanaey.

Since 1992, Igorot filmmakers have been representing themselves in their own language. In Benguet, the popularity of these films may be discerned in the vegetable transport vehicles that are marked with signs derived from these films. The songs included in these films have also been widely patronized. Initial productions were screened in church gatherings and other community events until demand called for distribution of VCD copies and further productions. There is now a thriving business in the sale of these films in Baguio stores, which also sell popular music by Igorot producers.

The production of these films was initiated by Sammy Dangpa, a Kankanaey video enthusiast from Buguias, Benguet, who founded the Vernacular Video Ministry (VVM), through which most of the films have been produced. At the beginning, the VVM was a one-man outfit, with Dangpa performing most of the tasks of film production. With equipment and funds donated by supporters, Dangpa produced films in partnership with local Protestant churches in Buguias, whose members served as volunteer crew members and talents. Most of the films are narratives about the clash between Igorot traditions and Christian beliefs, the influence of outsiders, the trappings and trends of modern living, and the desire for better living conditions. Many of the stories are anchored on biblical passages presented in text and voice-over, either at the beginning or end of each film. Some films include interviews with local folk. Some incorporate footages of cultural events in the Cordillera and videos of local and foreign locations.

VVM films that are in the Kankanaey language are Sabong di Kada (Flower of Kada), 1998; Adawag Ina (Mother’s Plight), 1998; Din Sungbat (The Answer), 2003; Kedaw (Ask), 2007; and Din Pantaulian (The Returning), 2008. Sabong di Kada is a film about a woman who longs for wealth, while Din Sungbat is a documentary-style film that highlights the differences between living in the mountains and life in the lowlands.

With the popularity of these films, other Kankanaey from Benguet and other ethnic groups in the Cordillera began making their own productions. A group from Mankayan, Benguet, called the Indigenous Film Productions, and Tribal Cooperation for Rural Development (Tricord) from Nueva Vizcaya released their first productions in 2007. These productions have similar themes as those produced by VVM, but other groups have ventured into generic themes that do not particularly take up matters of ethnic identity. Other groups have begun producing animation films that capitalize on the nuances of local practices for humor.

Sources:

Aguilar-Cariño, Ma. Luisa. 1994. “Eduardo Masferre and the Phillippine Cordillera.” Philippine Studies 42 (3): 336–351.

Allen, Janet. 1978. “The Limiting Glottal Infix in Kankanaey.” Studies in Philippine Linguistics 2 (1): 73-76.

Bagamaspad, Anavic, and Zenaida Hamada-Pawid, compiled. 1985. A People’s History of Benguet Province. Baguio: Baguio Printing and Publishing.

Baylas, Nathaniel IV, A., Teofina A. Rapanut, and Ma. Louise Antonette N. de las Peñas. 2012. “Weaving Symmetry of the Philippine Northern Kankana-ey.” Bridges Towson 2012 Proceedings, edited by Robert Bosch, Douglas McKenna, and Reza Sarhangi, 267-274. Maryland: Tessellations Publishing.

Bello, Moises C. 1965. “Some Notes on House Styles in a Kankanay Village.” Asian Studies 3 (1): 41-54.

———. 1972. Kankanay Social Organization and Culture Change. Quezon City: University of the Philippines.

Cabrera, Caroline K. 1977. “Tattoo Art.” In Filipino Heritage I, edited by Alfredo Roces, 141-145. Manila: Lahing Pilipino Publishing Inc.

Casal, Gabriel. 1986. Kayamanan: Ma’i-Panoramas of Philippine Primeval. Manila: Central Bank of the Philippines, Ayala Museum.

Casal, Gabriel, Regalado T. Jose Jr., Eric S. Casino, George R. Ellis, and Wilhelm G. Solheim II. 1981. The People and Art of the Philippines. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, University of California.

Demetrio, Francisco, Gilda Cordero-Fernando, and Fernando Zialcita. 1991. The Soul Book. Quezon City: GCF Books.

Dulawan, Lourdes S. 2001. Ifugao Culture and History. Manila: National Commission for Culture and the Arts.

Eugenio, Damiana L., ed. 1989. Philippine Folk Literature: The Folktales.Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Folklorists Inc.

Habana, Olivia M. 2000. “Gold Mining in Benguet to 1898.” Philippine Studies 48 (4): 455-487.

———. 2001. “Gold Mining in Benguet: 1900-1941.” Philippine Studies 49 (1): 3-41.

Hornedo, Florentino H. 1994. “The Bago Ballad of Delnagen and Annusan Lumawig.” Philippine Studies 42 (2): 217-246.

Keesing, Felix M. 1968. A Brief Characterization of Lepanto Society, Northern Philippines. Sagada Social Studies Series 13. Sagada: Igorot Study Center.

Lewis, Paul M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2014. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, 17th ed. Dallas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com/language/kne.

Llamzon, Teodoro A. 1978. Handbook of Philippine Language Groups. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Moss, Charles R. 1920. “Kankanay Ceremonies.” American Archaeology and Ethnology 15 (4): 343-384.

National Economic and Development Authority. 2014. “Historical Background of Cordillera’s Pursuit for Regional Development and Autonomy.” NEDA. Accessed 7 August. http://car.neda.gov.ph/.

National Statistics Office. 2002. “Benguet: Dependency Ratio Down by Four Persons.” NSO website, 26 April. http://www.census.gov.ph/content/.

———. 2002. “Mountain Province: Home of the Kankanais.” NSO website, 6 February. http://www.census.gov.ph/old/data/pressrelease/2002/pr0212tx.html.

Perez, Rodrigo III D., Rosario Encarnacion, Julian E. Dacanay Jr., Joseph R. Fortin, and John K. Chua. 1989. Folk Architecture. Quezon City: GCF Books.

Rapanut, Teofina A., Wilfredo V. Alangui, Henry N. Adorna, Arlano R. Aquino, Avelino P. Bucaoto, Edna M. Nazaire, Madelyn M. Ragasa, Reynaldo P. Rimando, and Reamar Eileen R. Sales. 1996. The Algebra of the Weaving Patterns, Gong Music and Kinship System of the Kankana-ey of Mountain Province. [Pasig City and Quezon City?]: Department of Education Culture and Sports and Center for Integrative and Development Studies.

Regional Map of the Philippines. 1988. Manila: Edmundo R. Abigan Jr.

Report of the Philippine Commission to the President, vol. 3. 1901. Washington: Government Printing Office.

Respicio, Norma A. 2000. “The Dynamics of Textiles Across Cultures in Northern Luzon, Philippines.” PhD dissertation, University of the Philippines – Diliman.

Santos, Soliman, Jr., and Paz Verdades Santos. 2010. Primed and Purposeful: Armed Groups and Human Security Efforts in the Philippines. Geneva: Small Arms Survey, Graduate Institute of International and Development Studies.

Scott, William Henry. 1969. On The Cordillera. Manila: MCS Enterprises.

Tindaan, Ruth M. 2010. “Imagining th Igorot in Vernacular Films Produced in the Cordillera.” The Cordillera Review 2 (2): 81-118.

Vanoverbergh, Morice. 1972. “Kankanay Religion (Northern Luzon, Philippines).” Anthropos 67: 73.

———. 1976. “Isneg and Kankanay Riddles Explained.” Asian Folklore Studies 35 (1): 37-166.