The Kalinga Tribe of the Philippines: History, Culture, Customs and Tradition [Indigenous People | Cordillera Ethnic Tribes]

“Kalinga” comes from the common noun kalinga, which means “enemy,” “fighter,” or “headhunter” in the Ibanag and Gaddang languages. The inhabitants of Cagayan and Isabela considered the Kalinga as enemies, since they conducted headhunting attacks on Ibanag and Gaddang territory. As such, the name is considered a misnomer, since it has no geographic or ethnic basis. Yet the term has become the official ethnic name accepted even by the natives themselves.

The number of culture groups in Kalinga varies according to different systems of classification. Nonetheless, authorities on Kalinga culture today agree that there are over 30 such groups. Northern Kalinga culture groups include Banao, Buaya, Dao-angan, Gubang, Mabaca, Poswoy, Salogsog, Ammacian, Ballayangon, Limos, Pinukpuk, Wagud, Allay / Kalakkad, Biga, Gamonang, Gobgob, Guilayon, Nanong, and Tobog. Located in Eastern Kalinga are the Dakalan, Gaang, Lubo, Majukayong, Mangali, and Taloktok culture groups. In southern Kalinga are the Bangad, Basao, Butbut, Sumadel, Tongrayan, Tulgao, Lubuagan, Mabungtot, Tanglag, Uma, Ablog, Balatoc, Balinciagao, Cagaluan, Colayo, Dalupa, Dangtalan, Guina-ang, and Magsilay-Bulen. Other culture groups are Aciga, Colminga, Dallak, Dugpa (Limos-Guilayon), Magaogao, Malagnat, Malbong, Minanga, Pangol / Bawac-Pangol, and the Kalakkad, also called Gaddang. Many of the Kalinga also identify themselves topographically with either “Upper Kalinga,” covering the more mountainous municipalities of Balbalan, Lubuagan, Pasil, Tanudan, and Tinglayan; or “Lower Kalinga,” composed of Pinukpuk, Rizal, and Tabuk.

The territory of the Kalinga used to be the southern half of the province of Kalinga-Apayao. On 14 February 1995, Republic Act 7878 separated Kalinga and Apayao into regular provinces. Becoming one of the six provinces of the Cordillera Administrative Region, Kalinga is bounded on the east by the Cagayan Valley, on the west by Abra, and on the south by Mountain Province. Its total land area is 311,970 hectares; its capital is Tabuk City.

The climate varies within the province, with a temperature ranging from 17 to 22 °C. The upper western half of Kalinga has a dry season from January to April and a wet season from May to September. March and April are the hot months. The eastern half of Kalinga has three months of dry season, with May and June being the hottest, and the rest of the year is rainy.

The province has a rugged and mountainous topography, cut through by the Chico River coming from Mount Data and emptying into Cagayan River. Chico River has several tributaries: Tinglayan in the south, Pasil in the middle, and Mabaka and Saltan in the north. Several small lakes can also be found in the Kalinga. There are wide plateaus and floodplains in Tabuk and Rizal.

A larger portion of the province is open grassland suitable for pasture, but the higher elevation in the west is forested by rich pine trees. Rizal and Tabuk, with their flatlands, are the biggest rice producers. The irrigated and rain-fed terraces in the other areas of the province also produce rice but on a lesser scale.

As of 2010, the total population of the province of Kalinga is 201,613, among whom 65.8% identify themselves as Kalinga, while the rest belong to other ethnic groups: Ilokano (18%), Bago (2.4%), Bontok (2.9%), Applai (2.2%), Kankanaey (2%), and Tagalog (1.1%). Several groups of Kalinga use distinct dialects or languages, namely, Lubuagan, Butbut, Mabaka, Limos, Majukayang, Tinglayan, and Tanudan. Ilokano is spoken all over the province.

History of the Kalinga Tribe

The Kalinga and other Cordillera peoples are believed to have arrived in separate migrations from southeastern or eastern Asia. The original migrants of northern Luzon might have had a common culture, but due to particular conditions of economy, water supply, population density, and ecology, cultural differences began to appear among the northern Luzon mountain peoples, resulting in the various ethnolinguistic groups: Ibaloy, Bontok, Ifugao, Kalinga, and Sagada.

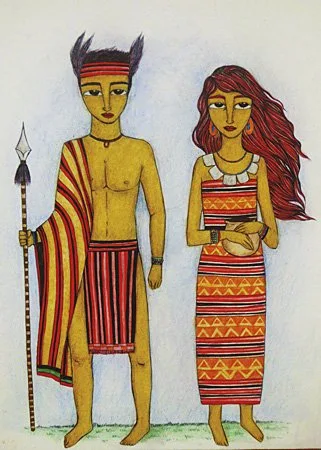

|

| Kalinga men and woman in ceremonial attire, early 20th century (Fowler Museum at UCLA) |

The original mountain peoples may have progressed from primary dependence on root crops until they developed swidden farming, then wet rice cultivation, and finally, irrigated terraced farming. But as the age of the rice terraces is hard to ascertain, it is difficult to establish exactly how long these peoples have lived in their mountain habitats.

The precious heirloom pieces of the Kalinga such as Chinese plates, jars, brass gongs, and agate beads, were handed down from generation to generation. They are good indications of fairly extensive pre-Spanish trade between Chinese traders and the Kalinga, and between lowlanders and the Kalinga. But such trading apparently stopped with the coming of the Spaniards. Spanish attempts to subjugate and control the mountain peoples had the following objectives: to exploit the rich gold deposits of northern Luzon; to extend or protect conquered territory; to convert the “pagans” to Christianity; and to discover exotic products. The Cordillera peoples fought and successfully repulsed Spanish control during the three centuries of colonial rule.

Gold was the main objective of Spanish incursions into Igorot land. Antonio de Morga, a Spanish chronicler, noted in 1607 that the Ilocano refined and distributed the gold mined by the mountain peoples. The Spanish monarchy under King Philip III was desperately in need of gold when Spain waged the Thirty Years’ War in 1618 against the Protestants and the Dutch. The king instructed Philippine Governor-General Alonzo Fajardo to befriend the Igorot to enable the Spaniards to exploit their gold mines. The Dominicans and the Jesuits rationalized military expeditions in 1620 as a mandate from God. But these and the gold explorations failed. The Spaniards were not able to occupy the Igorot gold mines for two centuries more.

|

| Kalinga couple (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The Kalinga area remained isolated and untouched by Christianity and Western European domination and became the refuge of lowlanders from Cagayan Valley, Abra, and Ilocos who resisted Spanish rule. The Dominicans who worked on the eastern side of the Cagayan Valley along the lower Chico River first attempted to Christianize the Kalinga, but there was no evidence that the Spaniards ever got closer to the mountain peoples other than through Santa Cruz and Tuga. In 1718, the Spaniards suffered a major setback when newly converted Christians of Cagayan Valley revolted. People of the missions sought refuge in the mountains. The Spaniards abandoned Tuao, Tuga, and Santa Cruz, and the entire missionary program declined after the revolt.

During the latter half of the 19th century, Spanish authorities created comandancias, political-military jurisdictions extending into the mountains of northern Luzon. Their purpose was to control tribal revolts and to protect Christianized lowland communities adjacent to hostile areas. The Kalinga were governed by the Comandancia of Saltan beginning 1859 under the newly created Isabela province. In 1889, jurisdiction over Kalinga was transferred to the Comandancia of Itaves in Cagayan province. However, the Spaniards failed to subjugate the Kalinga despite the undetermined number of military posts established within Kalinga territory.

Spanish influence was greater on the people of northern Kalinga than southern Kalinga. Geographically, the main entry into the mountainous interior had been from the north, until the American period when trails and roads from the south were constructed. Thus, trade and Spanish activities in the mid-1850s resulted in the acculturation of northern Kalinga.

Meanwhile, southern Kalinga, Bontok, and Ifugao were uninfluenced by both Spaniards and Christianized lowlanders. The culture of the southern Kalinga thus became similar to “cultures at the south of it” like the Ifugao and Bontok. Southern Kalinga apparently borrowed irrigated rice cultivation and other sociocultural traits from the Ifugao and Bontok.

Throughout Spanish rule, the local government system as headed by the appointed officials was not implemented. The most significant changes brought about by Spanish activities during the late 19th century was the improvement of trade and friendly relations among the Ilocano, Tinguian, and Kalinga. This was promoted through the existing trails that had been created to maintain military posts. Old interregional hostilities diminished, bringing about peace pacts and intermarriages among these groups.

During the 1896 Revolution, the mountain peoples spontaneously retaliated against the Spanish garrisons. They initially supported the Katipunero, since both lowlanders and uplanders suffered the same abuse and maltreatment from the colonizers. Although a civil government was established in the mountainous areas, the revolutionary government neglected the highlands, since efforts were concentrated in setting up a strong and effective leadership in the lowlands. Soon, the mountain peoples discovered that the conduct of the revolutionary troops stationed in the main centers was no different from that of the Spanish forces. Also, during the revolutionary period, social and economic conditions further deteriorated. Roads and trails were neglected, thus halting trade. Headhunting was resumed, internal warfare broke out among the mountain tribes, and agricultural activities were abandoned. As the Catholic missions withdrew, Christianized natives returned to their original religious practices.

During the Philippine-American War, 1899-1902, General Emilio Aguinaldo made Lubuagan the seat of the Philippine Republic for 72 days from 6 March to 17 May 1900. He had to abandon the camp, however, when the Americans started closing in on him. Passing through Tabuk, he escaped to Cagayan then to Isabela, where he was captured a year later.

The Americans, who were subtler in their colonial subjugation, pacified the mountain peoples by allowing them to practice their tribal lifeway and government. The Americans set up a separate form of government for the northern Luzon mountain region, as embodied in US President William McKinley’s instructions to the Philippine Commission in 1900. Dean C. Worcester, Secretary of Interior for the Philippines, was in charge of all non-Christian tribes except the Muslims. In 1901, the Bureau of Non-Christian Tribes under the Philippine Commission, which became a division of the education bureau in 1905, took the task of acculturating the mountain people. The initial task of the local colonial government was to establish law and order and build roads and trails. For example, the construction of a road into Baguio in 1905 opened the land of the mountain peoples to lowlanders.

In 1912, the Philippine Commission created the old Mountain Province composed of seven sub-provinces divided along ethnic lines: Amburayan, Apayao, Benguet, Bontoc, Ifugao, Kalinga, and Lepanto. In the 1920s, Amburayan and large areas of Lepanto and Benguet became part of La Union and Ilocos Sur, and other portions were added to Bontoc. Thus, such territorial change resulted in the five sub-provinces: Benguet, Bontoc, Ifugao, Kalinga, and Apayao. The Mountain Province was administered by a governor and each sub-province by a lieutenant governor.

In Kalinga, American rule was firmly established through Lieutenant Governor Walter F. Hale, 1908-1915, remembered by the Kalinga as “Sapao.” Although his dictatorial style was disliked by many, he was credited for having “pacified” the Kalinga. Under his leadership, headhunting incidents in the area decreased, and the bodong (indigenous peace-pact system) was strengthened.

Education, health, and sanitation became the focus during the second decade of American colonization. The main objective of colonial educational policy was to teach English. Particularly for the mountain peoples, the Bureau of Education formulated another objective: to provide vocational training to meet the special needs of the people. Health measures like vaccinations and medicines were enforced. Schools took up the issue of hygiene. Hospitals were established in Kiangan (Ifugao), Bontoc, and Lubuagan (Kalinga). Efforts were made by the American schoolteachers and missionaries in their education and conversion work to eliminate the Kalinga traditional belief that illness was caused by bad spirits. Three missionary groups pioneered in the missionary work in the Mountain Province: the Roman Catholic Church, the American Episcopalian (Protestant), and the United Brethren (Protestant).

During the Japanese Occupation, the mountain tribes remained loyal to the Americans. The Kalinga served as guerrilla warriors and provided refuge for the Americans. Missionary work and education came to a standstill.

When Philippine independence was declared on 4 July 1946, there was little change in the conditions of the Mountain Province. Kalinga became increasingly neglected, as evidenced by the poor maintenance and declining construction of roads and trails.

Then in June 1966, the old Mountain Province was abolished through Republic Act 4695. The act also created the new provinces of Benguet, Ifugao, and Kalinga-Apayao.

One important turning point in Kalinga recent history was the struggle against the Chico River Basin Development Project, a project of the Marcos administration funded by the World Bank. On 13 May 1975, 150 papangat (peacemakers) from Kalinga and Bontoc forged the Bodong Federation Inc., uniting themselves against the construction of four hydroelectric dams that would inundate their villages and rice fields. For the first time, the Kalinga and Bontok forged intertribal solidarity and declared their preparedness to resort to armed resistance to defend their ancestral domain. They sent petitions and delegations to Malacañan, but President Marcos dismissed their appeal as sentimental and urged them to make sacrifices for the sake of the nation’s progress. Marcos then sent military forces to the area.

The Kalinga set up barricades to prevent the entry of construction equipment and materials. The women tore down the soldiers’ tents while the men engaged the military at the dam site. In a protest march, 300 men and women took tents, cots, kerosene lamps, shovels, and all the construction equipment they could carry as they walked from late afternoon till early the next morning to the provincial military headquarters at the town center. In one episode, the women lay on the road to block the delivery trucks; in another, they bared their breasts to stop the soldiers.

The escalation of military operations in the area became a national and international issue, especially after Butbut tribal chief Macli-ing Dulag was killed on 24 April 1980 by soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Leodegario Adalem of the 44th Infantry Battalion. Simultaneously they strafed and set fire to the house of Pedro Dungoc, Macli-ing Dulag’s neighbor and spokesperson who had also written the pagta (law) for the bodong that unified the Cordillera elders against the dam. Dungoc escaped and went on to become a member of the New People’s Army until his death in 1985.

The slaying of Macli-ing Dulag further united the northern peoples. On 13 to 14 February 1982, another bodong was held involving leaders of four provinces: Mountain Province, Kalinga-Apayao, Abra, and Ilocos Sur. Adalem was sentenced to a 14-year imprisonment in November 1983, but militarization continued. The popular resistance of the Kalinga and other Cordillera peoples succeeded when the World Bank withdrew from the project in the early 1980s.

On 15 July 1987, President Corazon C. Aquino signed Executive Order 220, forming what is now known as the Cordillera Administrative Region (CAR) with its six provinces. Prior to this, Ifugao and the sub-provinces of Kalinga and Apayao belonged to Region II, while Abra, the City of Baguio, Benguet, and Mountain Province were under Region I.

Video: Ullalim; The Story of Kalinga

Kalinga Way of Life

Kalinga has agricultural, mineral, forest, and wildlife resources. The main agricultural product is rice. Principally rice growers, the Kalinga were once famous for producing and exporting large-grained rice. Traditionally, the most valued property is the rice field, followed by house sites. Other customary wealth indicators are livestock used in sacrifice and heirlooms like Chinese jars, plates, gongs, and beads. Kalinga is now the acknowledged “Rice Granary of the Cordilleras.” With an agricultural land covering 178,371 hectares, the province produced an average of 152,857 metric tons of rice from 2008 to 2010. Kalinga is regarded as the best producer of F1 rice, and its unoy variety is consumed widely both in the country and abroad.

|

| Kalinga farmers carrying rice harvest (SIL International) |

The southern Kalinga are predominantly wet rice cultivators while the northern Kalinga are dry rice farmers. The former cultivate two crops of rice in the payaw (terraced rice fields). The first crop planted during December consists of large-grained rice called unoy, planted along with glutinous rice called daykot. By June, the second crop called oyak are planted in house gardens and transplanted in the rice fields by July.

The Kalinga in the mountainous areas of the province grow rice in the payaw and in the oma or uma (swiddens). For the oma, they select a plot according to the ideal conditions of the soil, observe good or bad omens then clear the swidden before manosok (planting). Traditionally, planting starts with the prayer of old women. In one planting method, the men dig holes with a dibble stick, and the women drop rice into the holes. In another, both men and women dig holes and plant. However, irrigated rice farming, which is a more recent development in Kalinga agriculture, has fewer rituals associated with it than with swidden farming.

Corn is increasingly being grown in the province. As of 2008, corn production on Kalinga’s 7,757 hectares of agricultural land has grown to 38,833.75 metric tons. Other products are mango, pineapple, citrus, cacao, sugar, bananas, rambutan, and vegetables.

A booming industry in Kalinga is coffee production. The 3,000 hectares reserved for coffee plantations promise to produce over two million metric tons yearly. A popular coffee product is Kalinga Blend, a mixture of Arabica, Excelsa, and Robusta coffee. Two other coffee brands are Kalinga Brew and Mananig Coffee. Along with fruit and rice wines, these coffee products are slowly finding their way to national and even international markets.

Kalinga’s poultry and livestock industries produce chicken, ducks, mallards, pigs, goats, sheep, cows, and horses. Deer is domesticated in some villages. Carabaos, pigs, and chicken are often used for rituals. Carabaos continue to be used in farms, especially in the highlands, although in the flatlands of Kalinga, hand tractors are predominantly used. A few Kalinga still use dogs to hunt deer or wild boar. Almost 45 hectares of fishponds and 2.29 hectares of tilapia fish hatcheries are found across the province.

Manufacturing is also a growing business in the province. Forest products such as timber, rattan, and bamboo are used for furniture making and woodworking, which continue to be the dominant industry.

|

| Kalinga girl with a stack of water pots on her head (American Historical Collection) |

Other economic activities of the Kalinga are food processing, metal craft or ironworks, loom weaving, basketry, and pottery. In the past, the main material used for weaving was the bark of a variety of mulberry called sopot, manufactured into blankets and short jackets for men and women. Today, the center of the weaving industry is Lubuagan. Most of the raw materials come from outside Kalinga, and their woven products are increasingly influenced by contemporary fashion designs. The Banao people used to be the chief producers of spears, head axes, and knives, but blacksmithing in the area has declined. Some Kalinga craftsmen still engage in traditional blacksmithing on a limited scale. Metallic minerals found in the area are gold, iron, copper, molybdenum, silver, and zinc. Pottery and basketry are cottage industries. Pots continue to be used for cooking as well as for fetching water in some places. With increasing trade exchanges and exposure to urban life, the Kalinga now widely use modern cooking and kitchenware.

Many economic activities of the Kalinga are tied with cooperatives. As of 2008, there are 62 active cooperatives in the province, 22 of which are considered “millionaire cooperatives.” Tabuk Multi-Purpose Cooperative (TAMPCO) tops the list, with assets worth over 300 million pesos.

The Kalinga actively promote eco-cultural tourism, drawing local and foreign tourists each year. Each municipality has its own festival: the Manchatchatong (gathering) of Balbalan; Laga (weaving) of Lubuagan; Salip, an anagram of Pasil, the municipality’s name; Pasingan (wedding celebration) of Pinukpuk; Pinikpikan (native chicken stew) of Rizal; Matagoan (zone of life) of Tabuk; Podon (peace pact) of Tanudan; and Unoy (native rice) of Tinglayan. All these come together during the Ullalim Festival, which is a yearly agro-industrial and cultural fair in Tabuk that lasts up to five days. First held on 14 February 1996 to celebrate the founding anniversary of the province, it has become a grand yearly tourist attraction marked by street dancing, float parades, trade fairs, eco-trekking, white water rafting, and concerts. Lending grandeur to the 19th Ullalim Festival of 2014 was its “Awong Chi/De Gangsa” (Call of a Thousand Gongs).

Kalinga Tribal System

Kalinga became a separate province in 1995. Its eight municipalities have a total of 153 barangays. It is classified as a third-class province according to income. A governor, vice governor, and a provincial board administer the province. Kalinga is represented in the House of Representatives by one representative.

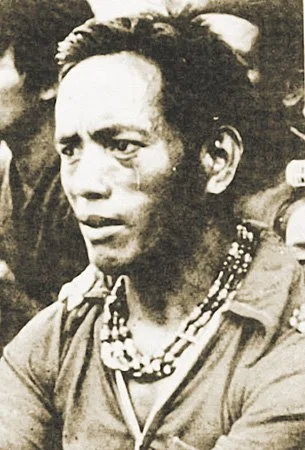

|

| Saking, a Kalinga warrior chief (National Geographic, 1912, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

Traditionally, the Kalinga acquired leadership based on formidable headhunting record, oratorical ability, and power to influence opinions. Courageous warriors were known as maalmot (brave warrior) or mingol (one who has killed many). The warriors believed that failure to avenge the killing of a tribe member by an enemy tribe was a disgrace. At present, the war record is no longer a requisite, but leadership remains in the hands of men with wide kinship connections, economic influence, oratorical ability, the capacity for the wise interpretation of custom law, and a record of having settled disputes.

In earlier times, the elders were the same people who got elected to public office at the provincial level, while some elders who were not qualified for municipal offices due to illiteracy might hold barangay positions. Now, elected public officials are a mix of old and young politicians who can afford to run a costly political campaign. Nevertheless, tribal elders who are peace-pact holders still play an important role in maintaining interregional peace.

The papangat or pangat are powerful men who act as peacemakers during periods of strife. As chief creators and interpreters of Kalinga custom law, they function as counselors and as chief negotiators in dealing with other culture groups. In the past, a pangat must first be a mingol, but this is no longer a prerequisite. The pangat are not elected into their position but merely “grow” into their social and political role as the people “just know” who has finally become one.

A village may have several papangat, but no central authority is designated. In meetings called the among de papangat, they convene to discuss intertribal problems and peace treaties. To resolve conflicts or disputes within a village, several pangat may act as negotiators or intermediaries. They try to resolve contradictions amicably, and no action or penalties are imposed that have not been agreed on. Absolute consensus, once reached, is expected to be carried out by everyone. Such is Kalinga tribal democracy.

In southern Kalinga, the pangat settle disputes involving killings over water distribution. The rice terraces are irrigated by a common stream or spring. If disputes arise due to scant water supply during the dry months, the pangat settle the problem by distributing the water equitably among the people. Thus, in southern Kalinga, the pangat are more influential than government or military officials.

The Kalinga legal system is based on Kalinga custom law, a body of regulations verbally transmitted from generation to generation. The pangat have extensive knowledge of these laws and pass judgments according to precedents. The complexity of Kalinga custom law illustrates their legal mindedness.

The bodong (pudon, vochong, and pechen in Bontok; kalon in Tinguian) forges peace among the Cordillera culture groups. It is instituted to end war among them; to establish peace and security for trade, travel, and commerce; to ensure justice when crime is committed; and to establish alliances.

Like the modern concept of the State, the bodong system has four basic elements: bugis (tribal territory), pagta (law), binodngan (people covered by the bodong), and sovereignty or recognition. The fourth element is seen by the intertribal pacts entered into by the Kalinga. It is also expressed in the principle of kulligong (to encircle). It means that the authority of the bodong extends to the binodngan and his or her property located outside the ili (village). Under this principle, certain places where the Kalinga reside, such as the cities of Tabuk and Baguio, are considered as matagoan (peace zones).

There were calls to abolish the bodong when some Kalinga used it to blackmail or bully binodngan and non-binodngan. Despite the abuses committed in the name of the bodong, however, this indigenous peace-pact system continues to be relevant to the Kalinga. Among the Cordillera groups, the Kalinga can claim a sizeable ancestral domain, mainly because of the bodong. It is also an effective tool in conflict resolution when implemented properly. In 2009, Tabuk City received the Galing Pook Award for its innovative and successful peace-and-order program through its Matagoan Bodong Consultative Council (MBCC). Created in 2003 as the Matagoan Bodong Council (MBC), the MBCC is composed of the city mayor as head, and dozens of male and female elders and leaders coming from the nine culture groups of Tabuk and representatives of the six municipalities. Binodngan and non-binodngan immigrant communities in Tabuk each have one representative in the council. The MBCC has been successful in resolving issues involving Kalinga and non-Kalinga residents in Tabuk through the bodong system.

The pagta di bodong are the laws governing the bodong that have been deliberated upon by the leaders of two conflicting tribes. They become operational once they are announced. Bodong holders used to commit the pagta to memory and pass these on orally. Today, all peace pacts are recorded in writing. The 1998 Bodong Congress in Tabuk adopted a new one or proto-pagta. This became the primary reference for specific peace pacts entered into by each Kalinga culture group. Generally, the pagta includes a preamble and about 15 articles. These articles include matters involving the bugis, the principles and policies of the bodong, nangdon si bodong (bodong holders), the binodngan and their rights, specific crimes and penalties, crimes against womanhood, and crimes against property. Several important changes have been introduced into the new pagta. One such change is the prohibition of automatic retaliation for offenses or crimes committed against a member of a Kalinga culture group. In the old pagta, the bodong holder and his relatives were expected to immediately avenge the death or injury suffered by a member of their ili.

Peace pacts in Kalinga are renewed through the dolnat or dornat, the terms used to refer to the gathering of representative of two ethnic groups with an existing peace pact. The ceremony is led by the mangdon si bodong (treaty holders). The mangdon si bodong may be a male or a female tasked to preserve the treaty by enforcing the bodong terms. The treaty holder must be able to settle disputes amicably once bodong terms are violated or when an intergroup war arises. Under the old pagta, part of their task was to kill a fellow tribe member who killed a kabodong (a member from a friendly tribe). Their responsibilities include the collection of indemnities from the kinship circle of a thief who is likewise a member of the tribe, and the delivery of indemnity in the form of money, heirloom, cattle, rice, and so forth, to the offended party. If the offended party’s demands are not met, the peace treaty is jeopardized.

Kalinga Social Organization, Culture and Customs

The household, the extended household, the kinship circle, and the territorial region are the significant units of Kalinga society. The boboloy or boboroy (Kalinga region) is the largest geographical unit, synonymous with “tribe” or “barrio.” The classes in traditional Kalinga society are the kapus (lowest class), baknang (propertied middle class), and kadangyan (upper class or aristocrats), to which the leaders of kinship groups and the pangat belong.

The Kalinga kinship circle or kindred consists of a person’s siblings, cousins up to the third degree, and ascendants up to the great grandparents and descendants down to the great grandchildren, including marriage partners. The kinship circle takes responsibility for the actions of its members.

The traditional Kalinga household consists of a nuclear family, which may include an old parent, or a grandparent of one of the spouses. Rich families may also have a poyong (servant). The extended family consists of two nuclear families living in separate households sharing the same economic tasks, such as planting rice.

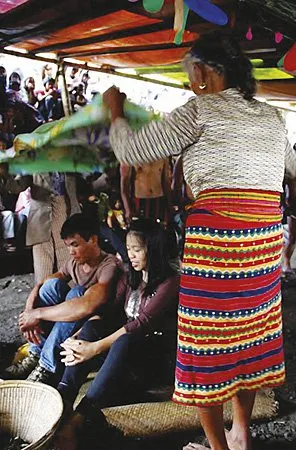

|

| Modern Kalinga wedding in Balatoc, 2012 (Milo A. Paz) |

Their life cycle has four important stages: birth, marriage, sickness, and death. Certain beliefs and ceremonies are associated with each stage. The Kalinga’s conversion to Christianity has discouraged these beliefs and practices, but they still persist among the Kalinga communities.

Pregnancy is marked by intricate rituals and observances that aim to protect the mother and the unborn child, and to facilitate easy childbirth. During pregnancy, both husband and wife must avoid places like pools and waterfalls where Ngilin, the malevolent pygmy-like water spirit, resides. Ngilin, who devours the unborn child, is said to be attracted by the smell of a pregnant woman. Objects like a piece of the sugaga tree bark and the tooth of a dog, crocodile, or ferret fox prevent Ngilin from smelling the fetus. Likewise, a pregnant woman must not eat eggs, which may cause infant blindness. She must not use a cup made of taro leaves because the child will easily be dominated by other children. To prevent breach delivery, other children must not sit by doors or windows. A father must not play the flute because this will produce a crybaby.

Delivery takes place within the house, and the extended family attends to the expectant mother. When the baby is born, it is not yet safe from Ngilin until observances are followed strictly. As soon as the baby is born, an adult member of the household places four knotted runo shoots outside every corner of the house, indicating visitation restrictions. The family observes these food taboos: beef, cow’s milk, eel, frogs, gabi (tubers), and dog meat. The father must not wander outside the perimeter of the village during the restriction period. When the baby is a month old, a medium comes to sweep the house with anahaw leaves, pronounces that the baby is already safe, and lifts the restrictions.

The Kalinga believe that babies attract malevolent spirits. Thus, the first 18 months of life are marked by a complex set of rituals known as kontad (northern Kalinga) or kontid (southern Kalinga), which protect young children from evil spirits. Having too many children is undesirable, because all children are entitled to share in the property of the parents and/or grandparents. Thus, abortion is a concern of the wife, the husband, and the kin whose share of inheritance might diminish because of too many offspring.

Grandparents play a major role in child rearing while parents work in the fields. During the first four years of childhood, there is no gender differentiation regarding the activities of boys and girls. Although boys and girls are treated equally, sons are still considered more important because in the past, men fought against the enemy tribes. Adults teach children about the kinship group’s history, its disputes with other groups, its vengeance and enmities. Also to be learned are the geography of their surroundings, names of the fields, folktales, legends, myths, chants, heirlooms owned by every household in the village, the process of crafts and arts, and the Kalinga custom law. In southern Kalinga, particularly Lubuagan, boys used to be circumcised at about age seven. The man who performed the surgery did not eat taro until the wound had healed.

Traditionally, marriages were arranged, but this is rarely practiced today except among wealthy families in southern Kalinga. The children were betrothed as soon as they were born. Through mangiyugod or mangbaga (go-betweens), the parents discussed proposals and arrangements. If omens were positive, close relations of the two families were sustained until the children matured. The families exchanged gifts and held a premarriage feast, in which the barat or ballong (southern Kalinga) or the kiling or kalon (northern Kalinga), was given by the boy’s parents to the girl’s. When the boy reached the age of 12 to 14, he was taken to the girl’s house by his relatives, who observed the omens and taboos. In the girl’s home, the boy fulfilled the custom of magngotogaw (bride service). When the boy reached the age of 17, he was formally escorted to the girl’s house by relatives other than his parents. This formal escort preceding marriage was known as tolod. A series of gift giving would take place between the two families. After two weeks, boy and girl could sleep together as husband and wife. Wedding feasts were competitive affairs, in which the kinship groups displayed their wealth. During this time, the parents of the couple also gave their share of the family inheritance, which might consist of rice fields, carabaos, Chinese jars, plates, and beads.

The Kalinga now choose their own marriage partners. Courtship begins when the boy tries to get the attention of a girl. The girl may give vague positive signs like a smile or a sudden lowering of the eyes. The emboldened boy then goes to the girl’s home in the evening to serenade her with songs like the ullalim or balagoyas. When the couple decide to marry, they simply announce it to their parents and set two dates for feasting—one hosted by the girl’s family and the other, by the boy’s. Today, most courtships resemble those in the rest of the Philippines.

Dagdagas (mistresses) used to be accepted in Kalinga society, with parental consent. The wife who was old or barren did not object if her husband took a mistress. Men with mistresses belonged to the wealthy class, whereas mistresses came from poor families. Children of mistresses were entitled to a lesser amount of inheritance. If the man had no children by his legal wife, then children from his mistress would enjoy the same privileges of inheritance as would his legitimate children. Under the new pagta, having a dagdagas is regarded as an act of adultery. Penalties in cash or in kind are imposed on the guilty individuals.

In traditional Kalinga society, the main reason for divorce is lack of children, but in rare cases, a man divorces a wife because of her rude behavior to his guests. Kalinga culture places a high value on hospitality. Today, some Kalinga couples separate for various reasons and seek annulment in the regular courts of law.

During illness, the mangalisig (“medium and healer” in the south) or mandadawak/mang-anito (in the north) appease the spirits of the dead or malevolent entities through animal sacrifices. The vigil over the dead, which was traditionally 10 days, now lasts for three days. The widow or widower sits beside the corpse. The spouse drives off flies with awasiwas (fly switch) while wailing and sobbing, asking the deceased not to send illness and to pity the living. Other relatives also sob and wail but do not sit near the corpse. The dead is buried near the house, the granary, or rice fields. Concrete tombs containing several deceased family members are common.

They observe a yearlong mourning, during which the closest relatives of the deceased are forbidden from eating certain kinds of food. Widows and widowers must not marry within this period. A feast of butchered animals, wine, music, and kolias (song) marks the end of the mourning period.

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the Kalinga People

The traditional Kalinga universe consists of five cosmic regions: luta, the cosmic name of the Earth, the central region of this universe; ngato, the skyworld where their supreme being, Kabunyan, lives; dola, the underworld, which is also inhabited by supernatural beings; daya, the upstream region that is the junction of the earth and the sky or the heavens; and lagud, the downstream region of the Kalinga cosmic universe and most inaccessible to man. The souls of the dead are said to enter the skyworld, where a special zone is reserved for them. The soul passes through the farthest region of the lagud when they leave the earth days after being buried. Once in the lagud, they ascend to their place in the skyworld.

|

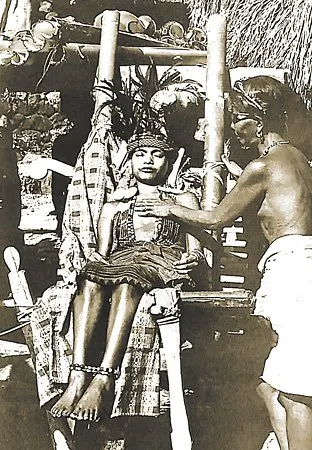

| Burial ceremony for an upper-class Kalinga girl (Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

The supreme being of the Kalinga is Kabunyan, who is said to have once lived with them. He is also believed to have taught them survival. Prayers are seldom addressed to Kabunyan because he is believed to have withdrawn his dominion over his creation. The Kalinga pray to nature deities called pinading. Nature deities protect and inhabit nature—forests, wild animals, birds, rivers, waters, and mountains. Everyone must ask these spirits for permission before taking anything from nature, and they must also thank these spirits afterward. Otherwise, the offending persons would be stricken with illness or death.

The alan are deities from other tribes which attack at night and are considered evil enemies. The Kalinga also pray to dead ancestors and relatives called kakkalading and anani, who protect them from the alan. The people also pray to mythological culture heroes who have individual names. The culture deities are those who assist the mediums or priestesses in the performance of rituals to drive away misfortune and evil spirits.

Traditional Kalinga rituals include chanting and sometimes require the playing of instrumental ensembles led by the mang-anito or mandadawak. These rituals range from simple hour-long rice rituals, to elaborate ones that last for three days, participated in by several mediums who chant together or alternately. Much preparation is needed for rituals related to kayaw (headhunting) and pasingan (wedding). Grave illnesses for which the anito ritual is performed require three mang-anito and the sacrifice of a large pig. These rituals have four forms: the dawak, which is the most important, the alisag, the sis-siwa, and the sapoy. During the dawak ritual, female mediums beat on a Chinese bowl while dancing and singing incantations. Upon entering into a trance, their movements become frenzied until they collapse.

Although most Kalinga today are Christianized, many still adhere to such indigenous beliefs and practices, which foreign missionaries have erroneously branded as “pagan.” In the 2010 census, which lists at least 45 Christian denominations in Kalinga, only 27 individuals (0.01%) identified themselves as belonging to tribal religions. Catholics are the most numerous, with 134,963 members, or 67.1% of the total population. Protestants (specifically belonging to the National Council of Churches in the Philippines) come second, with 19,615 members (9.7%); and Evangelicals (from the Philippine Council of Evangelical Churches), third, with 14,588 members (7.3%). Muslims count for 146 individuals (0.1%). Leaders of dominant religions wield a great influence on Kalinga politics, especially in matters involving peace and order.

Kalinga Tribal Houses and Community

Many Kalinga, especially those living in the hinterlands, settle on leveled or terraced areas on the slopes of steep mountains situated near waterways. Because of the prevalence of tribal conflicts in the past, the ili or village were located in strategic areas surrounded by difficult terrain where villagers could easily be forewarned against invaders or intruders.

There are three kinds of settlements: one with three to four houses, a hamlet of 20 or more, and villages of 50. Cement tombs may lie in the front yard of houses. The pappatay, the sacred tree, stands as a focal point of village life, both religious and secular. It is a sacred site where rituals are performed, but it may also double as a site for economic activities, such as that in Bugnay where it is also used for sugarcane milling.

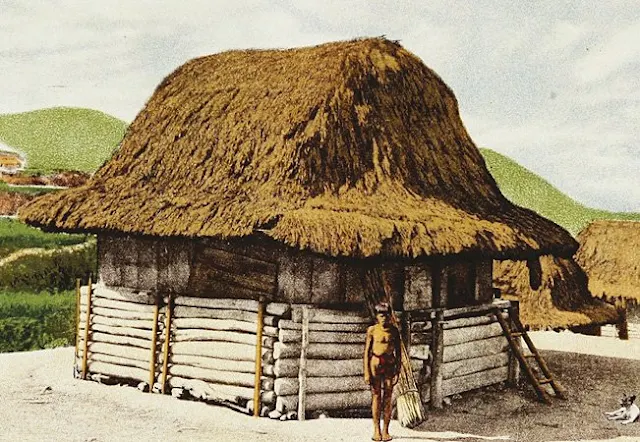

|

| A house on posts whose space underneath has been enclosed by logs, Lubuagan, Kalinga (National Geographic, 1913, Mario Feir Filipiniana Library) |

In the early decades of the 20th century, there were tree houses built 12 to 16 meters above the ground. A rope ladder, which could be pulled up at night, hung from the house and protected the occupants from enemy attacks. These houses have disappeared with the decline of headhunting and the prevalence of peace pacts.

The square-shaped Kalinga house is known as foruy in Bangad, buloy in Mabaca, fuloy in Bugnay, phoyoy in Balbalasang, and biloy in Lubuagan. It is a house elevated by posts, square or rectangular in shape, with a single room and split-bamboo flooring, which can be rolled up or detached for washing. In the past, the space underneath the house was enclosed by bamboo walling for protection against attackers.

Some houses also use pinewood for flooring, which would have three sections. The kansauwan is the middle section with two sides called sipi, which are the slightly elevated sleeping areas. At one end of the kansauwan is the cooking area consisting of a box of sand and ashes, and three large stones to hold pots. Above this cooking area is a drying and smoking rack. The only opening is opposite the cooking area—a small sliding door leading to a kalanga (small veranda). Walls are made of pinewood. Otop (roofs) are made of cogon and bamboo, or galvanized iron sheets.

The simpler kullub is described as a “square bamboo shed with an entrance at ground level and a partial floor at two slightly different floor levels on an independent set of posts” (Scott 1969, 216).

Wealthy families in the past lived in octagonally shaped houses called binayon or finaryon. Scott further describes the octagonal house of the Kalinga in Bangad:

... the three floor joists, two girders and four posts, which form the foundation of the house are called fat-ang, oling and tuod respectively, and riding on top of the joists are two beams or stringers that run from front to back called anisil or fuchis. Just beyond each of these stringers but not mortised into them, is another post set in the ground, and at equivalent distance from the center of the house; four more off to each side of the central four, giving a total of eight for the support of the wall. Across the tops of these outer (and lighter posts), and connecting them, are eight short sills (pisipis) grooved to receive the wall-boards (okong), the front and back ones being parallel, the two side ones being parallel, and the four corner ones joining them at 45° angle—producing that eight-sided plan for which the house is famous. The logs outside below the level of the floor are backed up against a sawali matting (dingding), which encloses the area beneath the house.

The reed-mat floor (tatagon) is laid down in the center section on laths (chosar), set into the top of the three joists parallel to the stringers, and in the two side sections on laths which run transversely from the outer edges of the stringers to the inner edges of the sills. Mortised into the upper faces of the stringers are four sturdy posts (paratok), two of which carry a crossbeam (fatangan), which, in turn, carries two light queenposts (ta’ray) supporting four crossbeams or purlins (ati-atig) in the form of a square. The rafters (pongo), fastened below the upper pisipis (beam of the outside wall), are bowed over these purlins and drawn together over three small ridgepoles which carry little actual weight but form the ridging (panabfongan). Despite the central square foundations and the octagonal floor plan, however, the roof with its ridgepole presents a different profile from the side ... the bowed pongo (rafters) are not duplicated on the front or back of the house; instead, straight rafters (pakantod) run up only as far as the ati-atig crossbeams. (196-97)

Upon entering the binayon, one senses the protective feel of the dome and the warmth emanating from the fireplace toward the rear, elevated slightly above floor level. Over this fireplace is a storage rack. Inside wealthy Kalinga houses are shelves or racks where heirloom pieces such as Chinese plates and jars are displayed. The display of family heirlooms is a status symbol among the Kalinga. Other Kalinga structures are the alang (granary) and the sigay (resting shed in the fields).

Today, traditional Kalinga houses are very rare. The wealthy Kalinga of today build modern, generic houses. Houses of wood, concrete, and galvanized iron with satellite television dishes are common even in the hinterlands of Kalinga.

Kalinga Arts and Crafts

The Kalinga are famous for their handwoven textiles, jewelry made of colored beads and shells, and metalwork like spears and knives. They also make household articles like wooden containers, bowls, dishes, ladles, and a variety of baskets and pots. They have grain containers made from hardwood, rice stalk harvesters made of carabao horn and iron, and digging sticks designed for planting rice.

|

| Kalinga kain or skirt (CCP Collections) |

There are two types of basketry used for daily work, which showcase the Kalinga’s fine craftsmanship and careful attention to detail. The labba is a bowl-shaped basket that exemplifies their fine wickerwork. It varies in size, from 20 to 150 centimeters in diameter. It has an evenly structured form with a square base and a round rim. The very fine, split-rattan weaves forming the weft uniformly rise on the sides. The round rim is carefully wrapped in split rattan or nito. Sometimes, this wrapping has a different color to serve as decorative contrast.

|

| Kalinga weaver using traditional loom (SIL International) |

A Kalinga burden basket, similar to the kayabang of the Benguet and the balyag of the Ifugao, is used with shoulder straps and worn as a backpack. This burden basket has a much deeper foot below the actual container of the basket—the Kalinga are taller than other mountain peoples and this structure facilitates the raising of the basket on their backs when they squat. Its square frame exhibits fine precision, the space between its splayed feet reinforced by a flat wooden brace, thus making it sturdy even under heavy load.

Up to the early 1970s, three remarkable forms of pottery were still being made in Kalinga but are now gone: the ceramic pot lid, the sugarcane wine jar, and the ceramic pig trough. The villages of Dangtalan and Dalupa in the Pasil municipality presently produce three types of earthenware or ceramic pots: the oppaya (meat or vegetable cooking pot), ittoyom (rice cooking pot), and the immosso, the globe-shaped water pot. The last has been made famous by the dance in which water pots in graduated sizes are placed on top of one after another and carried on the head by Kalinga women.

The standard-sized ittoyom has generally been replaced by the commercial kaldero (metal pot), but the large-sized ittoyom called lallangan continues to be used for communal celebrations and for basi (wine) fermentation. Potters coat their products, which they describe as “smooth, bright, shiny, and beautiful” (Stark 1993, 164), with pula (red ocher) to give these a violet hue.

In the late 1960s, Dalupa potters started to deviate from the traditionally globular shape of the immosso water pot to the more sharply angled one, which they call Binontok. Geometric designs on the immosso began in the mid-1970s when the Philippine government, at the height of the Kalinga opposition to the Chico River dam project, established a local-industry cooperative in Lubuagan. Here, the Pasil potters encountered newly arrived Kalinga weavers who advised them to add ocher designs similar to those on Kalinga woven textile. By the late 1980s, more elaborate and incised designs, such as flowers and anthrophomorphic figures, had been added.

Ay-ayam, literally “pets” or “toys,” used to be miniature clay pots made for children, particularly the im-immosso (mini-water jars). By the late 1980s, however, there were 50 different types of ay-ayam being made as souvenir items of various shapes and sizes: flower vases, money banks, candleholders, and the gusi (imitation Chinese porcelain jar). Young women are forbidden to make gusi, because these closely resemble the amuto vessel, in which dead infants were traditionally interred. In sum, the beauty of a ceramic pot, according to Dalupa potters, has the following features: a rim that is visibly turned outward; a long, graceful neck; coloring that is evenly spread; and a symmetrical shape and design.

Kalinga Traditional Costume & Tattoo Culture

The southern Kalinga differ in traditional wear from their northern counterparts. The southern Kalinga traditional male attire consists of a G-string called baag, a long, narrow red strip of cotton cloth with yellow stripes running lengthwise at equal distance from one another. This is worn between the legs and wound high and tight around the waist. The rich wear baag with broad patches of yellow designs at both ends, which may also have fringes, tassels, or round white shells. They have no upper garments except the blanket, which is rarely worn. The blankets reach the knees and are designed with multicolored checkered or cross-barred bands, with blue as the dominant color.

Ornaments worn by the men include C-shaped ear pendants similar to those of the Ifugao and the Bontok, a broad collar necklace called kulkul made of small beads of different sizes for special occasions, big copper bracelets, armlets, and necklaces of trapezoidal shells. During special occasions, they wear ostentatious head ornaments, with large feathers projecting upward at both sides of the head.

The southern Kalinga woman wears the kain, a wraparound skirt or tapis, which reaches below the knees and is worn below the abdomen in such a way that one of the thighs is exposed as she walks. But the hemline of the tapis that is worn for work barely reaches the knees. The tapis colors are predominantly red and yellow although other colors are also used. For special occasions, the kain is adorned with rows of oval shells intermingled with short strings of small beads. Traditionally, women wore no upper garments, but today, blouses and T-shirts are used. The hair hangs loose or is gathered in a string of beads called apungot, worn around the head. They tattoo their arms up to the shoulders and collarbone. A few dots are tattooed on the throat. The women wear earrings similar to those of the men. Other earrings are made of strings of small beads, large pieces of copper wires, and large pieces of shells. For necklaces, large beads hanging loosely over the breast sometimes reach the waist. Like the men, they may also wear the kulkul. They wear bracelets made of strings of beads. Traditionally, women were inclined to painting their faces red.

|

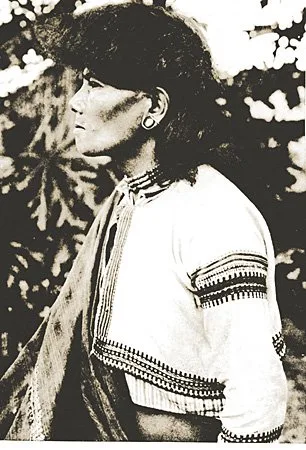

| Famous Kalinga tattoo artist Whang Od, 2014 (Fred Wissink) |

Tattooing is more popular in the south than in the north. The designs depend on a man’s bravery accomplished during tribal wars. Both men and women tattoo their arms, chest, and upper part of the back and face.

Video: The last Kalinga tattoo artist, Whang Od | DW Documentary

Recently, Kalinga was put on the global map when Whang Od of the Butbut culture group was featured as the last Kalinga tattoo artist in the television series Tattoo Hunter (Krutak 2010). Gisi, the traditional tattoo instrument, is made from buffalo horn, with gambang or steel needles on the tip. Manwhatok (tattoo practitioners) alternatively use parakuk id lubwhan (lemon thorns) to pierce the skin. Ink is made from charcoal powder or soot from pots.

Like the men of the south, the northern Kalinga men wear the baag, but with a multicolored upper garment called silup. This garment reaches about halfway between the neck and the waist and has long, narrow sleeves that reach down to the wrist. Very often, they use the blanket as upper garment. These blankets generally reach the knees and are woven with various colors and designs, with red as the dominant color. They carry a pouch of red cloth hanging from the neck. On special occasions, they wear a turban-like head cloth sometimes ornamented with feathers like those in southern Kalinga. They do not generally tattoo their bodies but those that do tattoo only a part of the forearm. For earrings, they embed the earlobes with rings made of black horn. They also wear the kulkul.

The northern Kalinga women wear the saya, an ordinary woman’s skirt covering the body from waist to feet made from a cloth of bright colors, predominantly red. They wear the same blankets worn by the men. The same kind of pouch hangs from the neck or is tucked at a strip of cloth at their waist. On special occasions, they wear a kerchief shaped like a triangle pointing to the waist, ornamented with coins and pieces of metal. They wear their hair long, usually knotted in a chignon, or tresses that may be intertwined with a narrow piece of cloth. Sometimes, a string of beads in place of the headband is used. They also tattoo their forearms and a part of their upper arms. For earrings, they wear the same types used by the southern Kalinga. They may wear necklaces over their breasts and use the kulkul on special occasions. They sometimes cover one or both forearms with strings of small beads. The women in the north paint their faces red. At present, the Kalinga wear contemporary clothing and put on traditional attire only for festivals and other such special occasions. One rarely sees a Kalinga male using the baag for daily wear, if at all.

|

| Kalinga grain container (CCP Collections) |

|

| Kalinga basket (CCP Collections) |

Among the traditional weapons and implements of the Kalinga are the sinawit sawit or gaman (head axe) and the bolo (long knife). Say-ang or tubay (spears) have various shapes. The kalasag (shield) is similar to those of the Bontok and the Tinguian: Three points project from the top and two points from the bottom of a sloping rectangular body. These shields supposedly represent the human body. The two prongs at the bottom are the legs, the middle section is the torso, and the top three prongs are the raised arms flanking the neck and head. They are lashed horizontally to their vertical plane so as to prevent splitting. Shields are painted with geometric designs similar to tattoo motifs, which may be related to death, burial, social position, or headhunting. These same designs also appear on lime containers and textiles.

Kalinga Literary Arts

Kalinga literature consists of riddles, legends, myths, and epics or ballads. The following are examples of Kalinga riddles (Eugenio 1982):

Appukedt sumacheg cha mangili, laligli. (Sagedt)

(Guess, when visitors arrive, it dances. [Broom])

Appukedt umamuy kedt anchu sumikedt kedt

chapillu. (Asu)

(Guess, tall when sitting, short when standing.

[Dog])

Appukedt ulas kun bilass leng misansancheg si

pinchong. (Tiyang)

(Guess, my sugarcane like the pine tree, leaning on

the side. [Rain])

The members of the Butbut culture group inhabit five villages of southern Kalinga: Buscalan, Lokkong, Butbut Proper, Ngibat, and Bugnay. Their riddle is the af-af-fok. In the following two examples, the images that serve as clues to the answers carry echoes of their militarized history, although the answers themselves are innocent enough (Lua 1994):

Affom:

Anna toro pulo wenno

afat a pulo a sorchacho

wa ummoy cha maarafan ad Kordilyera.

No mansubli cha ket

lamang cha mangangitit. (Sagkay)

(Guess what it is:

There were 30 to 40 soldiers

who went to fight in the Cordillera.

When they came back,

they were all black. [Comb])

Affom:

Toro chan mansafsafali

Lomnok cha kad chi kampo.

Ya lumawa cha kad,

Ossa-ancha. (Moma)

(Guess what it is:

They were three different things

When they entered the camp.

When they came out,

They were only one. [Betel chew])

Evidence of Macli-ing Dulag’s heroism is demonstrated in his statements of reproof against the manner in which the state intervened with the Kalinga way of life (translated by Yag-ao Alsiyao 2015):

Annaja papil osa lang na anana sa chugwa. Suyat gwenno pilak. Nu suyat achic ko akammo mang whasa, nu pilak maid ko ilac ya oc. Isu nga ayan ju na sobre anna ta lumagaw-aju.

Sayod suchon ju cha-ami nu ugwami na luta, ad asi aju mai-mis. Ah-gwanna titolon na luta ju? Amod whos na ingngangatu ju gwa u-gwa-onju na luta nga sija na masin u-gwa ah cha-aju. Sima ininum nga mang u-gwa sa siga na mawhigag ing-ingkana.

(This envelope can contain only one of two things—a letter or money. If it is a letter, I do not know how to read. And if it is money, I do not have anything to sell. So take your envelope and go.

You ask us if we own the land. And mock us, ‘Where is your title?’ Such arrogance of owning the land when you shall be owned by it. How can you own that which will outlive you?)

|

| Kabunyan hunting with his two dogs (Illustration by Luis Chua) |

One Kalinga legend explains why sacrifices must be offered to Kabunyan. Long ago, according to this legend, a handsome stranger with two dogs arrived at Dacalan. Wherever he went he emanated light, which astounded the whole village. The people discovered he was Kabunyan who had come down to earth. Kabunyan went hunting with his dogs in a mountain called Binaratan, where he caught and killed a deer with a full set of antlers. He singed its hair, gutted it, and cooked the heart and liver. Then he performed a ceremony called awad, in which he offered a share of the meal to the mountain spirits. The next morning, Kabunyan told the people of Dacalan that whenever they were to go hunting, they must perform the awad for the spirits who owned the wild game, and a share to be given to Kabunyan.

The myth of Lubting explains the peculiar shape of Mount Patokan. The uppermost slope of the mountain resembles a girl’s face when viewed from Tonglayan Village or from the road to Lubuagan.

Lubting was a beautiful maiden with a heavenly voice who started uttering ullalim-like melodies almost as soon as she was born. She rejected all her suitors except Mawangga from Tonglayan village, who became her husband. After six months of marriage, Mawangga decided to visit Tonglayan, promising Lubting that he would be back in five days. He told her to meet him on Mount Patokan, midway between Dakalan and Tonglayan. On the day of the meeting, the Tonglayan people had to fight Butbut warriors. Mawangga was beheaded by the enemy. His companions carried his headless corpse to Tonglayan and then informed Lubting, who was still waiting patiently on Mount Patokan. Lubting, in her grief, decided to die in the place where she was to meet Mawangga. She cried unceasingly, her tears causing landslides, which buried her alive. Her face, as legend goes, has not been covered by the soil to this day and is said to be the peculiar shape of Mount Patokan’s peak. Some Kalinga also associate this myth with the origin of the ullalim, the ancient ballads chanted by bards.

The Buaya and Aciga culture groups of northern Kalinga tell the story of the creator gods Kabunyan, Talanganay, and Patubog. Talanganay and Kabunyan created three people, but Talanganay could give life to only two that were finished. Talanganay made these two marry and their offspring were the first occupants of the area. He made the head of the third into a coconut, the arms into sugarcane, and the legs into banana plants for the people to have something to plant. Talanganay wanted the earth to be flat, but Patubog insisted on having mountains to prevent the people from feuding because they were multiplying too fast. To prevent people from dying, Talanganay tossed a gourd into the river, but Patubog threw a whetstone in it because he believed that too many people would run out of places to live in if they did not die.

Ballads that narrate the heroic exploits of culture heroes and emphasize the bravery and pride of the Kalinga people are sung in the musical form called the ullalim. Thus, these ballads may also have the generic name ullalim. Such ballads, taken together, may be considered an epic because these reconstruct the perils faced by the hero as he sets forth to lead a kayaw. The hero’s valor is contrasted to the rival’s cowardice. Furthermore, the hero has superhuman powers and mysterious skills aided by a magical head axe. The ullalim is also a romantic tale in which the hero fights for the maiden of his choice.

|

| Banna and Laggunawa (Illustration by Luis Chua) |

The ballads are chanted by male or female bards at night during casual gatherings or peace-pact assemblies. The most celebrated ullalim hero is a fearless warrior named Banna. The first song of the ullalim epic tells of the hero’s magical birth. The second song recounts his heroic exploits: Banna of Dulawon village sets out for the village of a wealthy maiden, Laggunawa, to make love to her, although she is betrothed to Dungdungan of Manila. She sleeps with Banna, but in the middle of the night Dungdungan arrives at Laggunawa’s house to assert his rights over Laggunawa because he has paid the bride-price. But Laggunawa, preferring Banna, tries to break the betrothal with Dungdungan by asking both warriors to go on a headhunting expedition in Bibbila, a hostile village. He who survives the expedition will win her. Banna goes to Bibbila and slaughters all its inhabitants. This becomes the first of his many exploits. Many bloody and heroic battles happen until the end when the whole village of Dulawon is burned to the ground because of Dungdungan’s wrath. The event paves the way for a peaceful settlement. Banna wins Laggunawa’s hand. Dungdungan is repaid the bride-price, and he marries Dinayaw, Banna’s sister. Peaceful relations are restored.

This excerpt describes Laggunnawa’s challenge (Billiet and Lambrecht 1970):

Nipun, kanu lummawa

si bubai’n mandiga.

Andi’n binalugnusna

duwa’n kabislan suga

Andi’n manbuwaanda,

da Bannay Dulawona

kan Dungdungan of Manila.

“Dungdunga a kapidwa,

anna manbuawaanta,

duwa’n kabisla’n suga,

ta inta mangalinga,

man-ilata midolpa

si kuliwog a pita.”

(Thereupon, kanu, came out

the lady dignified

There! she drew out

two sharpened canes

There! they get their share

Banna of Dulawon

and Dungdungan of Manila.

Banna says, “Dungdunga, my second cousin,

here is now the share for us both,

two sharpened canes.

For we are to go headhunting,

that we may see who will be dumped

into the pit of the earth.”)

Not all Kalinga culture groups have the ullalim. Oral histories trace the origins of the ullalim to the eastern Kalinga culture groups of Dakalan, Gaang, and Lubo, and later, to the Mangali, Taloktok, Tinglayan, Lubuagan, and Pasil. The northern Kalinga people call their epic the gassumbi, with a hero named Gawan. In western Kalinga, the epic is called dangdang-ay, and the hero is Magliya or Gono. The melodies and storylines vary in each region. Of the three epics, however, only the ullalim continues to be sung.

Kalinga Music

The Kalinga continue to actively preserve their musical heritage despite social changes. Traditional principles continue to underlie their music making, as seen in the technique of utilizing interlocking patterns in the various bamboo ensembles composed of leg xylophones called patatag or patteteg; stamping tubes called tongatong or dongadong; buzzers like the balimbing, also called bungkaka and ubbeng; quill-shaped tubes called patanggok, also called patang-ug and taggitag; parallel zithers called kambu-ut, also called tabbatab and tambi; and pipes in a row called sagay-op or sageypo or saysay-op. These ensembles, which generally consist of five or six instruments, have varying functions and are heard on different occasions, depending on the particular area within Kalinga.

|

| Kalinga musical instruments, from top: tungali, bungkaka, olimong, and patangug (Photos by Cesar Hernando, CCP/Lucrecia R. Kasilag Collection) |

Northern Kalinga children use the patteteg, ubeng, and saysay-op as toys. Elsewhere, the men play the pattatag to simulate the flat-gong ensemble. The taggitag are heard in big ritual celebrations played exclusively by men, whereas the tongatong are played by women in smaller rites for harvest and curing. In southern Kalinga, the bungkaka are sounded to drive evil spirits away as people travel in the mountains. The tambi ensemble is used in festive gatherings for entertainment.

|

| Kalinga men dancing with gangsa (A Philippine Album, American Era Photographs 1900-1930 by Jonathan Best. The Bookmark, Inc., 1998.) |

The ensemble instruments highly valued by the Kalinga are the gangsa (flat gongs), which are played in two styles: gangsa pattung, also known as gangsa palo-ok, and gangsa topayya or tuppayya. In the gangsa pattung style, the players each carry a gong and use a rounded stick to strike rhythmic patterns of ringing and dampened sounds. As they play their gongs, they move in circular formations with a group of female dancers. In gangsa topayya, each player uses his bare palms to play corresponding combinations of accented, dampened, and sliding strokes. A six-gong topayya ensemble consists of baba or balbal, referring to the largest and lowest-pitched gong; sobat or solbat; katlu (third); kapat (fourth); umut; and anungus, which is the highest-pitched gong. In a five-gong gangsa topayya, the fourth gong is the umut, and the fifth is the anungus. At festive gatherings, particularly peace pacts and wedding celebrations, the tadok is danced by a pair of male and female dancers to the music of the gangsa topayya. Flat-gong ensembles, as well as instruments made of bamboo, have patterns that interlock, and the varying accents produce consecutive ringing tones or resultant melodies.

|

| Kalinga men playing bamboo instruments at a wedding in Tabuk, 2016 (Cynthia Paz) |

Kalinga musical instruments that are usually played solo by men are the tungali (nose flute); beldong, also called paldong or padong (notched flute); ullimong (whistle flute); ullibaw or giwong (bamboo mouth harp); and onat (metal mouth harp). The nose and notched flutes have an average length of 60 centimeters. Both have finger holes and a thumbhole. Another solo instrument is the bamboo kullitong (zither), which has five to nine strings made by lifting up thin strips from the hard skin of the bamboo tube itself. Small, individual wooden bridges are inserted at both ends of each string. A more recent type uses metal strings and small stones as bridges.

To accompany songs, some Kalinga youth today use the kullitong, which is played by plucking the strings. The kullitong has a repertoire of solo pieces, in addition to its popular use in imitating the sounds of the flat-gong ensemble. Lastly, a musical instrument that is found only in the northeastern region is the giwong de malong-ag, a small mouth bow with two strings.

Kalinga vocal music is usually heard in social gatherings. They identify songs according to the melodies, with the corresponding texts determined by the occasion, varying with each rendition. Wedding and peace-pact celebrations are opportunities for hearing solo renditions of the ading, dango, and oggayam, as these are the vehicles for conveying greetings, or expressing feelings and opinions related to the event.

|

| Gangsa ensemble at a wedding, 2012 (Milo A. Paz) |

Most vocal songs have seven syllables per line, such as the ullalim, the epic of the eastern and southern Kalinga. The ullalim, as a musical form, is not restricted only to the chanting of adventure stories about epic heroes. The ullalim form might be sung in ceremonial occasions, such as the giving of advice to a wedding couple or as a welcome greeting to important guests. At someone’s request, one may chant her life story in the ullalim form, or one may be goaded into singing a few lines “as punishment for stealing a drink at a celebration” (Stallsmith 2007, 76).

The suggiyaw is a rice harvest song; dandan-ag, a funeral song; goygoy, a lullaby; tugom, a rice-pounding song; iwwayat, a debating song; and the dagdag-ay, a nostalgia song. The salidummay/dewas, probably the best known Kalinga song among many Filipinos, is metrical and most often sung in two-part harmony. Its melody comes closest to that of the generic Filipino folk song and may be of recent origin, possibly begun during World War II. In the 1970s, the salidummay was used as part of the Kalinga’s militant resistance to the Chico River Dam project (Sinumlag 2014):

Pasil, Chico, Tanudan

Lumigwat tako losan ay, ay

Ay, ay Salidummay

Ay, ay Salidum-salidummay

Sayang no dik ilaban

Pita un natagoan ay, ay

Ay, ay salidummay

Ay, ay salidum-salidummay

(Pasil, Chico, Tanudan

Let’s all rise ay, ay

Ay, ay Salidummay

Ay, ay Salidum-salidummay

What a waste if I cannot fight

For the land that has given us life ay, ay

Ay, ay salidummay

Ay, ay salidum-salidummay.)

Kalinga songs for the dead are the ibi, literally “to cry,” and in southern Kalinga, the dandannag, a song in praise of the dead. The rest of the vocal repertoire includes children’s songs, lullabies called wiyawi or wig-uwi, and various rice-pounding songs called mambayu, sung singly by a group.

Other types of Kalinga songs include the regam, which is about the rite of passage from boyhood to manhood; and the koggong, aimed to awaken the child’s senses. The tubag requests tribal spirits to bring the child prosperity and protection against disease, and the dopdopitis issung at the child’s first bath outside the house.

Kalinga Folk Dances and Rituals

“Tadok” or “tacheck” is the Kalinga word for dance. The tadok is mainly performed in a marriage ceremony. Sometimes it is referred to as a courtship dance, where a line of men and a line of women dance to the beating of the gongs. The pattong salip is a festival dance in which men and women form two circles, the women staying in the inner circle. The pattong salip is also performed during wedding feasts, with all the wedding guests collectively wishing the newlyweds happiness as a ring of men encloses the inner circle of women, who simply turn in their places (Orosa-Goquingco 1980).

The among is danced during an ordinary feast, where a group of dancers, led by the gong beater, dances in semicircular formation.

The tradition of fighting is likewise evident in Kalinga dance. The Kalinga pattong is a war dance where the dancers vow revenge for the death of a warrior. During the violent death of a warrior, all the males in the community get sounding sticks called bangibang, which they beat together as they jig toward a spot where future action might be decided upon (Orosa-Goquingco 1980).

The palok or paluk is another festival dance in which each male dancer beats on the gong to make the female dance. Courting is done in a dance called salip. Both male and female flap their arms, simulating the movements of a rooster and a hen, respectively. The men flourish their blankets toward their partners. The dance ends with the offering of the blankets to the female partner. In the salidsid dance, a Kalinga maiden expresses her choice between two men. The banga, or pot dance, is a work dance of Kalinga maidens who are famous for balancing on their heads several clay pots filled with water as they come home from the river where they have bathed and cleaned their wares. The steps exhibit the skill of hopping and stepping on the stones along the stream or river as they sing “Intaku Masasakdu” (Let’s Fetch Water).

Aside from the mimetic dances, one ritual of the Buwaya region in northwestern Kalinga may be called dramatic. The kayaw, which has two acts, is a narrative that relates how Bulla-ig goes to a suicidal headhunt at the edge of their cosmos after a quarrel with his wife over a woman. After he dies, his wife and sister refuse to come near his decomposing corpse, as represented by the lower hind leg of a pig tied to a stick. The ritual depicts the lowest class of demons, said to be the cause of disharmony between the husband and wife. The dramatic action depicts how disharmony in marriage caused by these demons can lead to separation and death. In the second act, the mediums call the alupag, which are spirits that speak through mediums during séances. The spirits arrive, ask where the corpse is, and carry it off with little respect—with buttocks toward the corpse to avoid its odor. They dump the corpse as they arrive near the place where the sacrificial elements are piled (de Raedt 1989, 185-188).

The bodong, besides being a political and social institution, is the venue for the performance of the people’s traditional music and dance. A specific example of the bodong as performance art is the three-day celebration that was held in April 2005 between the Kalinga Mangali culture group and the Kalinga Sumadel. The occasion was a galigad (transfer of the peace pact from father to son).

On the eve of the three-day celebration, 50 Sumadel visitors walk toward Licoutan village, which is the site of the bodong. As they do so, they play a lighthearted tune called the damilut on their saggaypo pipes. Alternatively, a popular entrance song that might be played is the salidummay. In reponse, six Mangali tribe members in Licoutan play the gangsa as they dance the tadok. A recent innovation is the inclusion of a woman among the tadok dancers, who are traditionally male only. After a supper of pork provided by the bodong holder, the Sumadel guests and the Mangali hosts alternately dance to the playing of the tadok and the tuppayya or topayya. A modern feature is a master of ceremonies who calls guests of honor to make speeches and then organizes group games. On occasion, a tadok competition might be held among the bodong participants, with the host offering an award. Toward midnight, the host treats everyone to a grander meal of carabao beef before they retire for the night.

On the second day, eight Mangali women, each representing her village, walk up to the makeshift stage bearing a basket of dekot (sticky rice cake) on their head. To the tune of the salidummay, they sing about themselves and their village, for example (Stallsmith 2007):

Inkanin makadongal bodong de Sumadel

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

Awad kad kaso ak dakkol adi ta Matokol

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

Annaya da dekotni bane Lower Mangali

We napulwan S. (2xs)

Okyan pasige takna (2xs)

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

Ta awad kad ayanta (2xs)

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

Pasigtaku nawaya (2xs)

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

(We are coming to listen to the Sumadel peace pact

celebration

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

If there is a big case, let’s not be surprised

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

This our sticky rice, we from lower Mangali

Where S. comes from [2xs]

May it always be like this [2xs]

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

So that if we go somewhere [2xs]

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay

We are always free [2xs]

Dang-dang-ay si dangilay isinalidummay.)

One woman’s presentation of her dekot might consist of lines improvised for the occasion, though chanted in the ullalim form, for example (Stallsmith 2007):

si dekotni inandila

we inkani igawa

atta susunud nanangindawa

kadi ummoy anamma

atte bodong appiya

si boboloy Bayoya

we kingwanda ummonunna

(our dekot which is like a tongue

that we entered with

to our siblings from the south

who are coming to decorate the

bodong of peace

in the village of Licoutan

that was made by the older ones.)

The galigad, which is the reason for the festivities, is followed by the dancing of five young women, improvised to the accompaniment of the baladong (flute) and the kullitong, each played by a young man.

Another part of the celebration is the tumangad, in which two large bowls of wine are passed around for the male participants of the bodong. A palpaliwat (poetic joust) is performed by the last pair to drink from their respective bowls. They try to outdo each other in recounting their successes in life, such as their political achievements. When they are done, another round of wine drinking would start with another palpaliwat with a different pair, and so on. Originally, the palpaliwat was between two warriors boasting of their head-taking prowess and other such feats of bravery.