Tiboli (T’boli) Tribe of Mindanao: History, Culture and Arts, Customs and Traditions [Indigenous People | Philippines Ethnic Group]

The Tboli, also known as T’boli, Tiboli, and Tagabili, are an indigenous people living in the southern part of Mindanao, particularly in the municipalities of T’boli, Surallah, Lake Sebu, and Polomolok in the province of South Cotabato and in Maasim, Kiamba, and Maitum in Sarangani. They can also be found in the neighboring provinces of Sultan Kudarat, North Cotabato, and Davao del Sur. There are four major lakes which are important to the Tboli: Sebu, the largest and the most culturally significant; Siluton, also called Seluton and Seloton, the deepest; Lahit, the smallest; and Holon, a crater lake of Mount Melibengoy in the municipality of T’Boli.

The name Tboli is a combination of tau, meaning “people,” and bilil or “hill” or “slope,” thus meaning “people living in the hills.” However, not all Tboli live upland: those inhabiting the shores of the Celebes Sea, in the municipalities of Maitum, Kiamba, and Maasim, are called the Tboli Mohin; those in the municipalities of Lake Sebu and T’Boli are the Tboli Sebu; and those on the western mountains near the Manobo are the Tao B’lai.

In 1988, the Tboli population was estimated at 227,000; by 2007, it had grown to almost double: 445,125. The Tboli language, along with Tiruray or Teduray, Blaan, and Ubo, belongs to the Bilic subgroup of the Malay-Polynesian division of Philippine languages. These four languages are of a different language family from that of the Manobo group in Mindanao.

History of the T'boli Tribe

Anthropologists say that the Tboli could be of Austronesian stock. It is believed that they were already, to some degree, agricultural and used to range the coasts up to the mountains. With the arrival of later groups, however, these people were gradually pushed to the uplands.

There is reasonable speculation that the Tboli, along with the other upland groups, used to inhabit parts of the fertile Cotabato Valley until the advent of Islam in the region, starting in the 14th century. The Tboli and their Ubu (or Manobo) and Blaan neighbors resisted the aggressive proselytizing of a succession of Muslim warrior-priests, the best known being Sharif Muhammad Kabungsuan from Johore in present-day Malaysia, who established the sultanate of Maguindanao during the late 15th and early 19th centuries.

According to the tarsila (Muslim oral accounts), those who accepted the new faith remained in the Cotabato Valley, while the others retreated to the relative safety and isolation of the mountains. Conflict between the Muslims and the non-Islamized tribes continued. Frequent slaving raids were conducted by the Maguindanaon Muslims on the non-Muslims, including the Tboli. Nevertheless, a regular volume of trade emerged despite the strained relations.

The fierce resistance of the Muslims against Spanish incursions served to insulate the Tboli from contact with Christianity and Spanish colonization. Only when the Americans were able to bring the Muslims under their sway, through a combination of military prowess and civil and religious accommodations, did Christian elements penetrate Cotabato and subsequently the hinterlands. Instrumental in this development was the collaboration of Datu Piang of Maguindanao, whose family was able to exercise considerable political power over the region during the American regime.

In 1913, 13,000 hectares of the Cotabato Valley were opened up for settlement, and the first wave of Christians arrived. In 1938, the Philippine government, in an effort to alleviate land pressures and arrest the concomitant rise of peasant revolts in Luzon and the Visayas, opened up 50,000 hectares in Koronadal Valley for homesteading. The trickle of immigrants gradually increased into major streams of Christians, especially from the Ilocano, Tagalog, and Visayan regions.

From February 1939 to October 1950, except during the war years, 8,300 families were resettled by the National Land Settlement Agency. These migrations adversely affected the Tboli. With the homesteaders came commercial ranching, mining, and logging interests. Armed with land grants and timber licenses, these individuals and companies increasingly encroached upon the Tboli homelands and displaced those who had resided on the land since prehistory. The Philippine government, which recognized only its own legislated instruments of ownership, did not provide the original inhabitants of the land legal protection from the newcomers. In contrast, except for the occasional presence of American troops in their territory, the Tboli were hardly affected by the Japanese occupation during World War II.

In 1966, the national government heeded the settlers’ call for the separation of the southern part of Cotabato province, thus creating the provinces of North and South Cotabato. The local government unit that was subsequently created inclined toward representing the migrants’ interests rather than those of the indigenous peoples.

In 1971, Manuel Elizalde, the head of the defunct PANAMIN (Presidential Assistant for National Minorities), announced the purported discovery of a Stone Age group called the Tasaday living in caves in a rain forest of the Tboli area of South Cotabato province. Subsequent studies since then have revealed that they are of the Cotabato Manobo group living in the Tboli area, and thus can also speak Tboli. Nearby are the Tboli village of Kemato and the Cotabato or Blit Manobo village of Teboyung. Tboli leaders attest that “Tasaday” is the name of the mountain peak where the caves are located. They have always gone to these caves, which they call Kilib Mata Awa (Caves of Mercy), for ritual prayers and for shelter when travelling or hunting.

In 1983, the municipality of Lake Sebu was carved out of T’Boli and Surallah municipalities despite resistance from the Tboli, who feared that the creation of the new municipality would further weaken their cultural and political control in the area. By 1983, the Visayan migrant settlers, who made up a mere one-fourth of Lake Sebu’s population, had acquired and controlled three-fourths of its choice land, which had once belonged solely to the Tboli. What was left to the Tboli was undesirable land. The opening of small-scale mining in 1989, the gold rush that followed in Kemato and T’Boli, and rattan gathering and logging by local and transnational companies have further shrunk Tboli territory.

Livelihood of the T'boli People

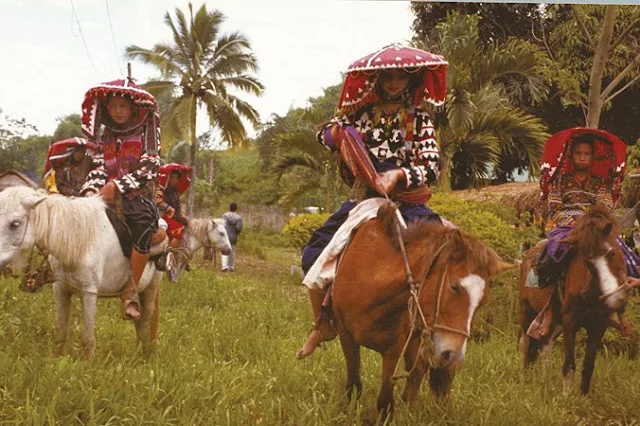

The Tboli were initially hunter-gatherers while being at the same time swidden farmers. Hunting with baho-ne-fet (bow-and-arrow) and sulit or soit (spear) used to be one of the prime sources of Tboli livelihood, supplying them with wild pigs, deer, monkeys, snakes, frogs, birds, and bats. The forests have also supplied them with rattan, bamboo, wax, honey, and other wild fruits and plants for their own use and as items for barter with neighboring groups and lowlanders. The rivers, lakes, and streams of the region supply them with fish, shrimps, and snails caught with fishing rods, spears, nets, and other traps. They raise ducks along lakeshores. They raise domestic animals, the most distinctive being horses, which enjoy a singular stature. Possession of horses is an indicator of financial and social prestige.

The Tboli society practices the kaingin or tniba (slash-and-burn) method of clearing land for farming. The whole process of tniba production, which begins with the search for an area to clear and ends with harvest, is from January to August. Fields are usually cleared with the bangkung (bolo) on hilltops where Tboli establish their homesteads. Besides mso (rice), which is their most important food, they plant sila (corn), kleb (taro), soging (banana), ubi koyu (cassava), ubi (sweet potato or yam), and various vegetables. Much of the produce is kept for the use of the household; some to barter for certain necessities like salt.

The Tboli are also skilled in textile weaving and metalwork, which enable them to produce the distinctive Tboli cloth known as tnalak and various metal artifacts ranging from swords to musical instruments and figurines.

Progressive contact with Christian lowlanders has greatly affected patterns of Tboli life. Increasingly, Tboli hunting grounds have been constricted by expanding Christian communities in the lowlands. Barter has given way to a money economy as well as the rise and expansion of “frontier capitalism” (Mora 2005). Household utensils, cosmetics, and certain fabrics are already being bought from stores in the lowlands rather than made by the Tboli households or bartered from other tribes. Lately, the sale of Tboli products has become a profitable business; the products are sold to tourists or sent to outlets around the country. However, Visayan settlers and merchants, who sell not only traditionally handwoven but also machine-made tnalak and other crafts, control the Tboli craft industry.

Pressure has been brought to bear upon the Tboli to open up their lands to contract-growing schemes for pineapple, coffee, cacao, banana, and other cash crops. It is a strategy adopted by the local government for lowland Christian farmers who have either abandoned their traditional crops or become employees of giant multinational fruit companies, canning factories, commercial ranches, logging areas, and mining pits. Many Tboli who have finished high school, technical school, or college are now dispersed not only in the country but also abroad, where they have found employment.

The Santa Cruz Mission has helped establish the cottage industry in Lake Sebu, where the Tboli produce crafts that are sold in the Mission’s various outlets around the country, including Manila. However, some tension has arisen between the Mission and its own former studentry, caused by a conflict of expectations based on cultural differences. The Mission’s concept of leadership, for instance, is based on authority whereas the Tboli’s is based on sbasa (reciprocity). Nevertheless, the Tboli have learned to use their culture to attract tourists to their area. The municipality of Lake Sebu is now a tourist destination, with students, scholar-researchers, and local and foreign visitors coming to watch the Tboli play their instruments and weave their garments. The Seven Falls zip line is an additional attraction for the more adventurous.

T'boli Traditional Village System

The concept of the village is nonexistent in the traditional Tboli political system since every house or household cluster operates rather independently, except during marriage and funeral feasts. The Tboli have the datu or chieftain to whom people go for interpretations of customs and traditions and for the settlement of intertribal disputes. Wisdom and proficiency in the knowledge of traditions are the deciding factors that make litigants consult one datu and not another. The community’s respect for the datu is based on his success, wealth, and the percieved righteousness of his life. His kimu (great wealth) includes suspended gongs, the klintang (gongs laid in a row), betel nut boxes, jewelry, and accessories. Because of his wealth, the datu can have many wives, though the libun gna (first wife) holds the greatest right and responsibility.

The position of datu is not hereditary. One datu does not enjoy primacy over the others, nor does he exercise specific jurisdictional control over specific areas or groups. Other datu might accord deferential treatment to one of their members, but this is not a sign of his superiority over them. A datu can forge an alliance with another datu through the sabila, which they must heed throughout their lives.

The highest honor for a woman is the title of boi, which is given to a wealthy female or to the favorite wife or daughter of a wealthy male or a datu. She is expected to be adept at supervising her household, which may include her husband’s other wives; forging economic and social ties with her community; and practicing Tboli arts and crafts, namely, “weaving, brass casting, embroidery, hat making, and fine beadwork” (Mora 2005, 36).

The Tboli are traditionally governed through a rich layer of custom law and tradition. There is no body of written laws, and neither does the datu rule by decree. Some Tboli communities have maintained their institutions such as the kukum, their traditional justice system. The udin are officials selected from a group of known, trustworthy, and respected people to enforce the rules that fall under kukum. The genlel and mogut kukum, for instance, settle and pass judgment or punishment in cases of crimes and disagreements. Under the mogut kukum are the hemyu, who mediate between two families seeking mutual revenge. However, these roles and power are now held by the local government police and trial courts. A clear influence of migrant settlers, for instance, is the fulis (police), who apprehend law offenders.

Custom law and tradition are usually inculcated among the Tboli in the numerous folktales and folk beliefs that are transmitted orally from childhood. Sala (transgressions of the custom law) do not have a corresponding penalty in the penological sense. Rather, offenses are penalized by tamok (fines). If unable to pay the tamok, which is usually in the form of land, horses, cattle, money, or other movable or immovable property, the offender must render service to the aggrieved party for a period of time.

Grave felonies and transgressions of custom law that would bring harm to the community can be punished by ostracism and, in extreme cases, death. The henihol, a punishment system no longer practiced today, includes death as the gravest sentence, especially for murderers and adulterers. In henihol, the offender is tied to a post in the victim’s yard and made to die a slow and painful death.The Tboli believe that violations of custom law and tradition are also punished by the gods, so the perpetrator is doubly penalized. Disputes arising from contract, quasi-contract, and the interpretation of custom law are decided by the datu after consultation with elders of the tribe who are known to be well-versed in tribal tradition.

To the present day, the datu is still respected as a cultural and social leader in certain Tboli groups. However, they no longer hold political power equal to the elected and appointive officials in local government units, which are led by a mix of indigenous people and migrant settlers.

T'boli Culture, Customs and Traditions

Video: Preserving Culture, The T'boli of Mindanao, Philippines, part 1

Rice is a core value of Tboli culture. Besides being the most important food, it is also the main object of sbasa or the reciprocal exchange of labor and goodwill. Each family has a sfu halay (spirit owner of rice), which is wrapped in sticky rice from the family’s last harvest and kept in a tukung tahu (true bowl) in the house. Their cropping calendar begins with the sfu (rice-planting season). Their term for unhusked rice, halay, also refers to the calendar year, and the terms for the different stages of rice production are the names of the months of the year.

Saif, which means (site selection), is also their word for the month of January, which is when they start the search for a field to clear. The rhythm of nature corresponds with the phases of tniba production. Saif is also the time of the year when the kloto and dof trees shed their leaves and fak-selel frogs appear in great numbers. By the time the fields have been cleared, summer has set in, and the fields are allowed to dry. This is also when the kloto and dof trees bloom and the fak-selel frogs lay their eggs.

Sbasa is the communal system by which all stages of rice production are accomplished. The call of the muhen (omen bird) signals the start of the twimba (clearing of the field). The head of the family then calls upon relatives and friends to help him and his family with this labor-intensive task. The women slash at the small trees, bushes, grass, and weeds; the men cut down the big trees. The host family provides meals and sfmak (betel chew). When the cutting is done, the family members do the remainder of the work. The father and sons burn the field; the wife and daughters plant corn and cucumber the next day. They hold a ritual called halay libut in the middle of this new clearing: around a small house or platform that they have built for their sfu halay, they plant the seeds of sticky rice.

Mehek (rice planting) begins when the Blotik Ehek star appears in the night sky sometime between March and April. Again, sbasa is organized for the planting activities. With their dibble stick, the men poke holes in a row into the ground, and the women drop the seed rice into the holes, over which they sweep a covering of soil with their foot. Mehek is also the Tboli term for “making the hole” while m’la is for “placing the seed in the hole.” Speedy and rhythmic coordination is required between the men and women as they take turns poking, dropping, and sweeping. At day’s end, the host wife prepares n’kem, literally “handful” but customarily a basketful of rice seeds, which she gives to each woman before dribbling logom (hand-sized bundles of harvested rice heads) in a crisscross fashion on top of each basket of rice. The recipient will take this basket of rice seeds home either to plant in her own family tniba or to prepare these for her family’s meals.

The sfu ends with the muta (harvest) in July or August, depending on the varieties planted. During the harvest, the women cut the stalks and the men tie the harvested rice into bundles. The rice is stored in a granary, which is either in the tniba or near the house. The host family holds a kmini pinipig (parched rice feast) to celebrate the first harvest. The women of the host family gather a few baskets of pinipig (parched rice), while their men hunt for game to serve at the feast. When all the families have harvested their rice, all with the sbasa system, the end of the whole rice-production process is celebrated with the s’gaan (reciprocal rice harvest feasts).

The Tboli are organized around the household and rarely settle in a cluster larger than three to four houses. Traditions are preserved through generations because of the tightness of the family. The older members teach the young ones their ketol (genealogy), the ways to maintain their land and other wealth, and the knowledge and skills of their culture.The Tboli value wealth highly, differentiating people according to socioeconomic status. A clear distinction is also made between the roles played by males and females. The father is the head of a household and wields power and control over its members. Tradition dictates, however, that this power should not be arbitrarily exercised and that his word is absolute only in major decisions. For example, he cannot treat his wife like a slave.

The Tboli are very solicitous with their pregnant women. For one, they are not left alone, lest they be preyed upon by the busaw (evil spirits). Thus, a pregnant woman is warned: “Bathe not in the lakes nor rivers or the busaw will kidnap your child and turn it into a fish.” A pregnant woman is spared most household and fieldwork tasks, even such routine chores as cooking, because she might “bear a child with huge eyes.”

Likewise, her food intake is regulated. She cannot eat twin bananas, lest she bear twins or triplets, forcing her to choose one, regardless of sex, and bury the other(s) alive to prevent bad luck. Nor can she eat the legs of pigs, chicken, or deer; otherwise, the unborn child will be toothless or have enormous teeth. Eating chicken gizzards or leftovers is believed to lead to difficult childbirths.

Some beliefs are similar to those of other regions. For instance, a woman should be cheerful and careful in preserving her good looks so that her child will be born pretty and good. Conversely, an expectant mother shouldn’t listen to stories about the busaw for her child will be born evil.

A pregnant woman who comes across a snake in the fields will die in childbirth. Those who are fond of sitting near the hearth or the stairs will have difficult deliveries. During childbirth, the umbilical cord must not go to the baby’s head or the child will grow up to be antisocial. If this happens, it is better to kill the child. Even the man has to observe certain practices during his wife’s pregnancy. A woodcutter, for example, must arrange his logs well, lest his child be delivered feet first.

Prenatal care uses augury techniques to deliver diagnoses. To determine the cause of a pregnant woman’s premature pains, an old woman versed in the healing arts places a white chick under the house, immediately below the spot where the patient lies. Should the chick chirp, the child is deemed to be sick; otherwise, it is the mother who is sick. The old woman then prepares the necessary concoctions to relieve the ailment.

A woman may resort to abortion for various reasons: her husband has abandoned her and refuses to give support; she has more children than can be fed adequately; her honor has been stained; or she wants to be spared the difficulties of delivery. The woman goes to the tau matunga (abortionist), who gives her concoctions. Failing this, more drastic measures are taken, such as self-injury or walking around with heavy stones tied to the womb.

The moment the mother-to-be experiences labor pains, a monkey’s intestines are placed on her abdomen in the belief that this will ease childbirth, because monkeys always have easy deliveries. The husband assists the midwives during his wife’s delivery, and he places personal items, like his tok (sword) or kfilan (long knife), by her side as desu (offering to the gods in supplication for easy childbirth). Another tok is used to cut the baby’s umbilical cord. This tok has a mystic life-bond with the child and must never be lost, lest the child die.

The mother wraps the child in her luwek (tube skirt) and allows no dressing to be applied on the newly severed umbilical cord. Henceforth, she resumes her normal routine, free from the lii (taboos) that governed her pregnancy. The child is bathed for the first time on the underside of an ancestral gong because of the belief that this would give the child good health and a strong soul. The child is allowed to remain naked until it decides to emulate its elders and dresses accordingly.

Children are named according to their physical characteristics at birth, such as bukay (white or light-skinned), udi (small), or bong (big). Sometimes, they are named after important ancestors, forces of nature, or animals. If the child is a first-born, the parents are identified by the child’s name. Thus, the parents of a child named Fok come to be known as Mà Fok (Father of Fok) and Yê Fok (Mother of Fok).

Disrespect for parents or disobedience to them may result in the child being bartered, a practice known as habalo. Destitute parents may also resort to this to meet their credit obligations. Filial obligation, however, dictates that the relatives of the parents buy the child themselves, or buy back the latter should he or she be sold to a nonrelative. Once sold, the child ceases to have all relations with the original family. The Tboli custom of respecting their elders in all aspects of day-to-day activities is still strongly followed today. Disobedience to this rule is believed to bring, at the very least, a curse or misfortune upon the defiant one.

Tboli upbringing is not strict. The indoctrination of the child into the rigid rules of Tboli society is subliminally and relentlessly pursued through the numerous folktales and beliefs that are told and retold. These didactic exercises contain various lii. Among the beliefs expressed is a whole class of injunctions against eating certain types of food such as the bedak (jackfruit) growing against the branch, which will make the children rebellious; the head of a pig, which will bring about hardheadedness; frogs heads, which will cause talkativeness; burnt rice stuck to the pot bottom, which will lead to laziness and unruliness; chicken wings, which will bring about boys unable to build a house or girls unable to weave; and rats, which will turn the children into thieves.

Succession is exclusively reserved for men. When the father dies, his responsibilities and rights go to his eldest son. In a practice called lomolo, if the deceased has no son, his eldest brother inherits not only his wealth but also his wives. Daughters, however, do not inherit property.

Because Tboli society operates within the concept of sbasa, they always see themselves in relation to others. Chewing betel nut, a common practice until today, signifies the many variations of this Tboli core value. It is done to welcome guests, help them decide matters, commence meetings and gatherings, and express feelings. Chewing betel nut together means an agreement is reached between the parties present.

The moninum, which celebrates the unity and alliance of a bride and groom’s respective clans and friends, is held in the spirit of full reciprocity. Tboli kesiyahan (marriage) is a long process that may be conducted in three major stages: childhood, puberty and adolescence, and the crowning celebration, which is the monimum. Marriages are prearranged by the parents and may be contracted at any age, even immediately after the child’s birth.

Child betrothals may be the result of a child’s sickness. If a child is sick, an augury is made, using a pendulum made of a handful of soil wrapped in a piece of cloth tied with a string called the hamkowing. The question of whether or not the child is banahung (in need of a life partner) is asked. The hamkowing replies by spinning clockwise or counterclockwise. Another way of determining if a child is banahung is through the dmangao, in which a medium makes measurements with the palm. If the child’s pinky does not meet the medium’s pinky at the end of the measurements, then the child needs a spouse.

Once the child is known to be banahung, the parents seek a spouse of suitable age, family background, and economic standing. When the prospect is known, the sick child’s parents borrow a piece of the chosen child’s body adornments from the latter’s parents. This is placed first on the healthy child then brought to the sick child over whom it is suspended, then struck.

Upon the sick child’s recovery, its parents go to the prospective spouse’s parents and make arrangements for the celebration of the first of the marriage ceremonies. On the date set for the latter, the parents of the girl go to the house of the boy and discuss with his parents the sunggod (bride-price) and the kimo, composed of movables and immovables to be given by the families of the bride and groom which will comprise the paraphernal property of the bride.

This is done over a drawn-out feast called the mobulung bahong, lasting three to seven days. Once the sunggod and the kimo are agreed upon, the contract is sealed with the promise of delivery by the boy’s parents of the sunggod, which usually consists of horses, carabaos, agong (gongs), land, or other valuable properties. Afterward, the boy and the girl sleep together and are covered with a kumo (handwoven blanket).

The next phase is the mulu, a reciprocal feast hosted by the girl’s parents. Again, the betrothed sleep together. The mulu lasts exactly as long as the mobulung bahong. At the end of the mulu, the date for the wedding is set, which may well be far into the future. At this point, in the eyes of Tboli society, the child-spouses are already married.

Gatoon is the period between the conclusion of the contract and the solemnization of the marriage. During this period, the boy visits the girl’s house, performs various chores for his in-laws, and if he so desires, sleeps with his spouse. His parents, on the other hand, gradually fulfill the provisions of the kimo. Should one of the children die, the practice of lomolo is followed, that is, a close relative is made to take the place of the deceased. If the other party does not accede to this substitution, the kimo is returned. Short of death, the marriage may still be called off and the sunggod returned.

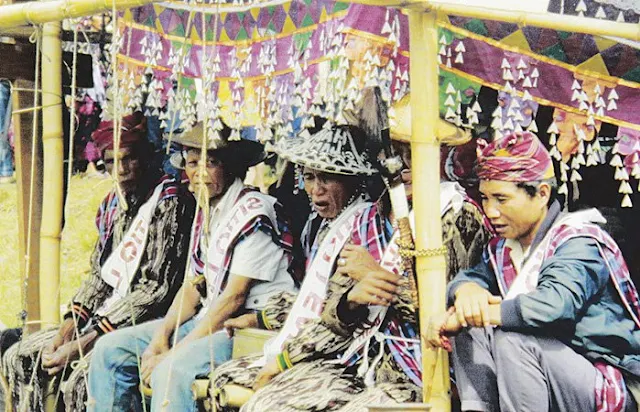

Years later, when the children shall have reached puberty, the exact date of the solemnization is set, usually on a full moon when no rain is expected, and the marriage is celebrated at night in the bride’s house. For the occasion, the house is be spruced up, with displays of swords and kumo magal (handwoven blankets) on the walls and rafters, and igam (mats) and tilam (cushions) on the floor. The boy and the girl dress up in their respective houses; then, they go separately to their respective venerable elders, who sprinkle water on their feet, hands, and face. As they return to their respective houses, they must be careful not to break a twig because this would presage bad luck. All throughout the afternoon prior to the ceremonies, and as the preparations get underway, there is continuous playing of the agong, hagalong (two-string guitar), and tnonggong (deerskin drum).

The groom is informed when the bride is ready in all her wedding finery, and he proceeds to the house of the bride at the head of his entire entourage. The bride awaits her groom while seated on a cushion in her house’s lówó (central space), with another cushion placed beside her. She is covered with a kumo immediately prior to the entry of the groom. From that moment on, no one may go near her except for the old person who had sprinkled her with water earlier in the afternoon.

The groom enters the house accompanied by his sister or any other female relative, who directly goes to the bride, removes the kumo, and kisses her. The kumo becomes this person’s property, and she in turn must give the bride a gift proportionate to the value of the blanket she has just removed and acquired. The groom is made to sit on the empty tilam (cushion or soft pillow) next to his bride, taking care not to touch her. Only then are the groom’s other relatives and guests allowed into the house. They are made to sit on the groom’s side and may not talk or mix in any way with the bride’s relatives and guests until the marriage ceremonies are over. The bride’s sister or other female relative reciprocates the removal of the bride’s kumo. She removes the groom’s turban and lays it beside him in a ceremony known as hamwos olew.

The wedding feast is initiated by the elders who sprinkle water on the bride and groom. The bride’s elder feeds the groom and vice versa. The two elders initiate the first touch between the couple by making their knees meet. This becomes the act of union, which is followed by the couple eating from a single plate, an event accompanied by hearty applause and approval from the assembled guests. This then is the cue for relatives of the bride to seek out “partners” from the groom’s side to feed. The latter show their appreciation by giving a gift to the person feeding them. Throughout the meal, everyone is careful not to drop anything. Silence is kept and sneezing suppressed, as a sneeze is considered bad luck for the couple.

After the meal, the parties of the groom and bride, represented by their respective hulung telu (singers), engage in the slingon (debate in song). The topics invariably lead to a comparison of the qualities of bride and groom, becoming an occasion to finalize negotiations on the final amount of the sungod and kimo. The klakak or hlolok (the chanting and singing of the exploits of Todbulol/Tud Bulul, an epic Tboli hero) follows after the slingon. This lasts until daybreak.

The following morning, the delivery of the kimo is completed while the groom ventures to the woods and cuts a tree branch. He puts this in the hearth of the bride’s house. The young couple can stay in the bride’s house, where they are taught the ways of married life until the branch dries up. This period of their marriage is known as the siyehen. After the siyehen, the couple moves to the groom’s house, where the marriage ceremony (except for the removal of the kumo and the turban) done at the bride’s house, is repeated.

The moninum is a series of six feasts, hosted alternately by the families of the bride and the groom. Done over a two- to six-year period, the moninum is an optional celebration that only the wealthy Tboli can afford. Each feast runs for three to five days and nights.

For each occasion, a gunu moninum is built to house the guests who would be coming from all over. Along the long wall of the gunu moninum where the entrance lies, a wall consisting of kumo hung side by side is set up. These are the contributions of the bride’s relatives. Opposite the gunu moninum, a tabule (a portable house-like structure) is built where contributions by the groom’s relatives are hung or attached. These items include plates, cloths, umbrellas, agong, and horse bridles.

The first day is invariably given to accommodating the arriving guests. The festivities begin on the second day. There are koda seket (horse fights), where horses from the groom’s party are pitted against horses from the bride’s side, with each party waging bets. The matches are one-on-one affairs, but each side has about 15 to 20 horses, sometimes even more. The horses fight until one flees from the field, in which case, a new pair is brought in to do battle. Horse fighting enthralls the Tboli as much as cockfighting does other Philippine ethnic groups. There is continuous feasting, and the nights are devoted to singing the exploits of Tud Bulul.

Aside from the horse fights, dances are performed on the square. One such dance is the tao soyow, where two men, one dressed as a female and representing the groom’s side, stage a mock fight. The dance lifts the lii or taboo from the kumo. The climax of the festivities comes when the party of the groom lifts the tabule and carries it across the square, “penetrating” through the wall of kumo hung on poles lifted by relatives of the bride. This manner of entry purges the lii that the groom and his relatives were under.

Polygyny is allowed among the Tboli, a practice resorted to especially by chieftains and the wealthy. The Tboli epic hero Tud Bulul set the example, since his adventures usually ended with his gaining an additional wife. A man may take another wife with the consent of his first wife. This is seen as prestigious and advantageous, as extra wives mean extra hands in house and field work.

The grounds for divorce include incompatibility, sterility, and infidelity. In cases of adultery, an unfaithful wife caught in the act may simply be killed on the spot—as was the case with Ye’Dadang, a married woman who was hacked to pieces by her irate husband when he caught her and her lover. The event was made into a popular Tboli song. Another consequence of divorce is the return of the bride-price should fault lie with the girl.

The Tboli do not regard death as inevitable; rather, it is the result of a trick played by the busao or busaw (evil spirits), or a punishment inflicted by the gods. This is rooted in the belief that one’s spirit leaves one’s body when one is asleep, and one awakes the moment the spirit returns. Thus, should the spirit not return, death occurs. The Tboli refrain from weeping upon a relative’s death, hoping that the dead person’s spirit has just strayed and will soon return. It is for the tau mo lungon (the person who makes the coffin) to determine if the deceased is indeed dead.

When the tau mo lungon arrives, he feels the hands and feet of the deceased. Once convinced the person is really dead, the tau weeps aloud. Only then do the members of the dead person’s household start weeping. Disposal of the dead may take the following forms: burial, abandonment in the house, cremation, or suspension from a tree in the case of small children. Wakes last anywhere from a week to five months, depending on how much food and consumables the dead person’s family has, since all these must be consumed before the corpse is buried or abandoned.

Tools for making the coffin are provided for the tau mo lungon, and these subsequently become his. He measures the corpse, summoning and invoking the deceased person’s spirit. The tau mo lungon then goes into the forest and fells a tree, from whose trunk the lungon (coffin) is to be fashioned. Before cutting down the tree, the tau mo lungon asks permission from Fun Koyu, god of the forests, through a short invocation. After the tree has been felled, the tau mo lungon and his companions sit down to eat and apportion part of their meal as an offering to Fun Koyu.

After the meal, the tau mo lungon and his party start carving the lungon. As the lungon takes its final shape, it is beaten along its convex exterior with tubol (pieces of bamboo) to drive out the busaw and prevent them from inhabiting the hollowed-out cavity before the corpse is laid in.

The finished lungon is beaten anew for around an hour then brought up into the house. The deceased is laid inside the lungon with all of his or her most important personal possessions, which are believed to be necessary in the afterlife. Then the relatives and friends file past the lungon and touch the corpse as a gesture of farewell. When all of the friends and relatives have touched the corpse, the lungon is closed. Once the lid is put in place, all the grieving and lamentations stop to prevent the dead person’s spirit from returning. The lungon is tied firmly with three rattan strips and hermetically sealed with damay, a very strong glue, to seal in the smell of decay.

The lungon of a prominent and beloved datu is suspended over a fire, and the salo (grease) that seeps out through the wood is gathered into bowls. This is then served as a camote “dip” which the people partake of, in the belief that the qualities of the datu will be passed on to them.

The lungon are then decorated with symbols of the man or woman’s occupation. The tau mo lungon has to sleep three nights in the house of the deceased after decorating the coffin, lest he fall sick.

The wake lasts until all movable properties are sold off and the harvest is consumed. To conserve anything would offend the dead person and cause the person’s return. During the wake, there is singing, dancing, and the chanting of nged (riddles) to provide entertainment, so that people do not fall asleep. The Tboli fear that the busaw will steal an unattended corpse.

On the morning of the funeral, the tau mo lungon fills a kobong (bamboo container) with water and suspends this over the lungon end corresponding to where the corpse’s head is. If the level of the water falls during the course of the day, another death is forthcoming.

The Tboli bury their dead at night. Before the lungon is brought out, the coffin maker splits the kobong wide open, prompting the mourners to shout aloud. Then the coffin is carried around the house and taken out. Only the male relatives proceed to the gono lumbong (burial site), and they take turns carrying the lungon. The tau mo lungon leaves the house last, taking with him a cock in the bend of one arm and a jar full of cooked chicken. If the cock escapes, it means he has taken an evil spirit with him.

After the lungon has been buried, the mourners partake of a meal, a portion of which is left at the grave. After the meal, the mourners return to the dead person’s house, in single file and by a different route. Upon reaching the house, the mourners must leap over two swords stuck in the ground in the form of an X to rid themselves of evil spirits that may have accompanied them back. Then, the bereaved household and all those who went to the burial bathe themselves in a nearby river, thus rinsing off all the evil spirits that have clung stubbornly to them. Afterward, the house of the dead person is burned or abandoned completely. This effectively ends the death rituals as the Tboli do not as a rule mourn their dead, for fear that the deceased would come back to life.

Changes in the Tboli’s circumstances have greatly diminished the relevance of their traditional social practices to their present lives. Arranged marriages, which include the payment of the sunggod, are no longer practiced today, as more women receive basic and tertiary education and work afterward. The tradition that allows men to marry multiple wives as long as they can support them is no longer a norm either, mainly due to financial and religious reasons. The children no longer play or know the sudul, a game that involves the use of shields.

Video: Preserving Culture, The T'boli of Mindanao, Philippines, part 2

Religious Beliefs and Practices of the T'boli People

The Tboli’s supreme deities are a married couple, Kadaw La Sambad, the sun god, and Bulan La Mogoaw, the moon goddess. They reside in the seventh heaven. They begot seven sons and daughters who married each other. Cumucul, also Kmokul, the eldest son, was given a cohort of fire, a tok or sword, and a shield. Cumucul is married to Boi Kahil. Sfedat, the second son, is married to the second daughter, Bong Libun. This marriage produced no progeny, leading to Sfedat’s despondency. One day, he asked his wife to kill him. His corpse became land from which sprouted all kinds of plants and trees. Dwata, the third son, is married to two of his sisters, Sedek We and Hyu We. His request for one of the powers granted Cumucul was refused. Thus, he left the sky with his wives, his six children from Sedek We, and his seven children by Hyu We: Litik, the god of thunder; Blanga, the god of stones and rocks; Teme Lus, the god of wild beasts; Tdolok, the god of death; Ginton, the god of metallurgy; Lmugot Mangay, the god of life and of all growing things; and Fun Bulol, the god of the mountains. For a place to stay, he asked Bong Libun for the land that was once Sfedat’s body. Bong Libun agreed on the condition that she marry one of his sons. Dwata spread the land and planted the trees and other vegetation, the result of which was the earth.

|

| Tboli elderly leading a ritual with lighted torches in cross shape, Lake Sebu, South Cotabato, 1990 (CCP Collections) |

The first people were created after Dwata breathed life into the clay figurines made by Hyu We and Sedek We. When Dwata did not fulfill his side of the bargain with Bong Libun because his sons did not want her as wife, Bong Libun married her youngest brother Datu Bnoling. With him she had six sons, who became scourges of the earth: Fun Knkel, god of fever; Fun Daskulo, god of head diseases; Fun Lkef, god of colds; Fun Kumuga, god of eye afflictions; Fun Blekes, god of skin disease; and Fun Lalang, god of baldness. To alleviate the damage done by these scourges, the divine couple, Loos Klagan and La Fun, assume the role of healers.

One of the most influential figures in the Tboli pantheon is the muhen, also called limuhan or lemuhen, a bird considered the god of fate, whose song when heard is thought to presage misfortune. Any undertaking is immediately abandoned or postponed when one hears the muhen sing, and the Tboli stay inside their houses until the next morning. Other Tboli groups, however, see the call of the muhen as a blessing and approval of whatever they are doing. The muhen has three distinct calls: if they hear the sound of the kutel’s krrr krrr krrr behind them and they do not stop what they are doing at once, this means that a loved one will soon die; if they hear the kutel’s cry in front of them, this means they will be facing serious difficulties. If the call, however, is heard from a distance and to the person’s left or right side, they will be successful in their current endeavors. The call of the glung predicts the difficulties ahead of the person if they continue what they are doing. The call of the kukut, which sounds like kut kut kut kut, foretells danger. To counter the bad omen, one must give cooked rice and a ring or a little gift and address the muhen with a plea not to come around foretelling danger. The Tboli say that the muhen came into being when the sky-reaching kekem tree was chopped down, and the chips that flew off to the east became the muhen bird.

The Tboli believe in the busaw or malevolent spirits, which wreak havoc on the lives of human beings, causing misfortune and illness. They are also described as ghoul spirits who are known to “gnaw, chew, or eat the dead raw” (Awed et al. 2004, 167). Desu or propitiatory offerings of onuk bukay (white chicken) or sedu (pig) are made to placate or gain favors from these evil spirits. Tboli rites are normally presided over by a morally upright elder, usually the datu, who is proficient in Tboli tradition.

To the Tboli, all objects house a spirit. They continually strive to gain the good graces of these spirits by offering them little gifts. Before crossing a river, for example, they may throw a ring. If spirits or gods need to be appeased, the Tboli make desu, which may consist of cooked food, the agong, and the kfilan or sword.

The Tboli afterlife has several destinations. Murder victims and warriors slain in battle go to a place called Kayung, where everything is red. The tewol (mountain apple tree) is associated with Kayung. One who eats its fruit cannot go back to earth. Entry into Kayung is announced by the sound of agong, klintang, hagalong (two-string guitar), and dwegey (violin). Thunder and lightning during a burial signify a spirit’s entry into Kayung. Suicides go to Kumawing or Bulul Kemowing, where everything sways and swings. Victims of drowning become citizens of the sea. Those who die of an illness go to Mogol, where day is night and night is day. It is described as a dark place; thus, the Tboli have tattoos on their chest that shine in the dark. The Tboli welcome rain after a death, the belief being that the deceased has crossed the bridge to the afterlife with no intention of returning.

The Tboli believe that their ancestors reside in Lemlunay, between the sky and the earth. A ladder, which only the tau bulong des (shaman) can see, connects Lemlunay and the earth. Lemlunay is described as paradise because of its fertile soil, lush and thick hardwood trees, and abundance of fruits. It is also called Kulu El (The Main Stream), Lunay Mogul (Beautiful Mountain), Bungtud Kefung (Mountain of Dust), and Lemkulen (Inside the Tree).

Preparations for tnalak weaving are preceded by ritual prayers. The tnalak process starts with the abaca being cut down and its fibers stripped. The person who performs this task does so with this prayer: “Tenahu hu Fu Kedungon, Fu K’nalum, Fu Loko, ne Fu Dalu, yom taha ye. Ni bangkong ni belay me ebelem-em ani heyu nim tnalak ni ne efet kol be kdengen” (I call on the spirit of abaca, the spirit of Knalum, the spirit of Loko as well as Fu Dalu, the owner of all things. We offer this knife to you so you may ensure our success in the creation of tnalak, so that no illness will descend upon us until we have finished our task) (Paterno 2001, 41-42). The Tboli believe that a spirit resides in every woven tnalak and that the designs are taught by the spirit Fu Dalu to weavers through kna (dreams). These designs are passed from one generation of weavers to another.

Such beliefs and rituals have been considerably watered down since the arrival of the first Protestant missionaries at Lake Sebu in the late 1950s, together with waves of Visayan homesteaders. The Catholic missionaries came in 1961 and established the Santa Cruz Mission as well as educational facilities in the area. Since then, many Tboli have joined the Catholic, Protestant, and other Christian denominations. These changes are mainly attributed to intermarriages with Christian migrant settlers and conversions by several religious missions in their area. Interactions with neighboring Muslim groups have also resulted in Islam conversions.

These new beliefs have heavily influenced Tboli society and culture. Dress codes are imposed by certain sects, especially at worship gatherings. These new beliefs, however, have not totally supplanted the Tboli’s traditional faith. Masses and worship services, for instance, are conducted in Tboli, which is also the language of their Bible and worship songs. Their belief in Dwata has become synonymous with the Christian concept of God. The merging of traditional and new beliefs is illustrated by the Lemlunay, a harvest festival initiated by the Santa Cruz Mission. The Lemlunay festival is a fusion of Catholic rituals and symbols with the Tboli belief system and mythology. As a result, it has taken on the trappings of a mardi gras, with “a costumed procession, masque, and allegorical tableau” (Mora 2005).

T'boli Traditional House and Community

The Tboli consider the household as the basic social and economic unit; hence, they do not have villages. At most, they form clusters of three or four houses whose occupants are close relations. The gunu (houses) are built on hilltops, primarily for security. Tboli houses are not permanent because of tnibaor slash-and-burn farming, which exhausts the land after a number of years; the kimu, the transfer of property on the occasion of a marriage; and the practice of burning or abandoning houses and moving whenever a member of the household dies.

From afar, a Tboli gunu bong (big house) appears like one big roof on stilts. The roof eaves overhang beyond a meter over the side walls barely one meter high, hardly noticeable. The stilts are nearly two meters above the ground, making the house look like it is “hovering over” its site. In the laan gunu (space underneath) are tethered horses, a valuable Tboli resource.

The average gunu bong is about 15 meters long, 9 to 10 meters wide, and about 6 meters high, from the ground to the roof’s peak. The roof has a low slope of 30°. The Tboli roof is made of cogon or other dried grasses that are strung and sewn to the bamboo rafters with strips of raw abaca or way ng yantok (rattan strips). The stilts are of bamboo, except for the rooted tree stumps used occasionally as posts for the inner portion of the house floor. The walls of the house are usually of lasak, a very elementary type of sawali consisting of bamboo split from the inside and flattened out, or of woven bamboo strips called lahak.

The interior can be broken down into roughly seven areas: the lówó seel (central space), blaba (side areas), desyung (area of honor), dofil or dfel (sleeping quarters), dol bayul (vestibule), bakdol (entrance), and fato kohu (utility area).

The lówó seel is the main feature of the Tboli gunu bong. Measuring approximately 5 by 7 meters, its flooring is 20 centimeters lower than the floor level of the surrounding spaces. The lówó seel serves as the central space around which are done all household activities, such as eating, weaving, and resting on ordinary days; chewing betel nuts at wakes; and singing traditional songs on special occasions. At night, it serves as extra sleeping space. The floor of the lówó seel is made of the finest lasak.

The blaba lie on both the long sides of the lówó seel and are around 2 meters wide with flooring also of lasak. The blaba are for sitting, working, and conversing. The meter-high walls of the blaba have tembubong, sections made of lasak hinged onto the blaba floor, which can be released outward, looking like an extension of the blaba floor.

Opposite the entrance area, the desyung completes one end of the gunu bong, adjoining the lówó seel and the two blaba. At its center, adjacent to the lówó seel and under the klabu, is the area reserved for the head of the house—the place of honor that commands the view of the entire house’s interior. The head of the house sleeps in the desyung, where the family’s material wealth is kept; this may include a wooden chest containing accessories, clothes made of tnalak, betel nut containers, and musical instruments. The klabu is a curtained canopy adorned with a wide band of appliques and tassels. This canopy is bought from Muslim traders, and its quality is an indicator of the Tboli family’s wealth and stature. On either side of the klabu are spaces considered places of honor on which igam or mats are spread and tilamor cushions and pillows are piled as seats for important guests. The number of igam piled one on top of the other is an indication of the family’s standing. These mats are left permanently spread out. To tuck them away, the Tboli believe, would cause the death of a household member.

The dofil or dfel, where the relatives and children sleep, lies hidden at the back and either side of the desyung. Lahak beng (sawali partitions that extend up to the roof) separate the dofil from the blaba. Some houses have the dfel tau mogow, where transient visitors stay for the night. The entire desyung-dofil complex occupies one end of the house, spanning the entire width, and is about four meters deep. The floor is made of lasak laid crosswise. Lahak beng at times divide this area into cubicles for each of the wives, who sleep there with their children.

The dofil can often include or be transformed into a tbnalay, which serves as sleeping quarters for the young unmarried women in the household or for the first or favorite wife. The tbnalay is elevated almost 1 meters above that of the lówó seel’s level. This attic-like area is enclosed with lahak beng, with an opening either toward the lówó seel or the rest of the desyung-dofil area. The space underneath the tbnalay is often used as a working area, especially for households engaged in metal working.

The dol lies opposite the desyung, at the entrance end of the lówó seel. At one end of this two-meter-wide area that crosses the whole width of the house is the bakdol and, at the center of the remaining three-fourths, the kohu (hearth). Although on the same floor level with the lówó seel into which it opens to the right as one enters, the dol bayul area should be classified as a different section of the house. When the house owner allows guests into the dol bayul, this means that they are welcome. Those who are not welcome stay outside the dol bayul. It is the only portion of the house that is floored with heavy planks.

The hearth or kohu is defined from its surroundings by its four posts and a beaten-earth floor on which fire is made for cooking. These four bamboo posts, which support the roof, like all the other bamboo posts in the interior, also support the hala. This is a shoulder-high rack on which pots, baskets of different sizes, ladles made of coconut shell, and other cooking utensils are placed or suspended.

Suspended from the hala or from any of its posts is the kalo, a loosely meshed network of rattan strips shaped according to the contour of the plates and bowls kept in it. Until some decades ago, antique Chinese plates were commonplace in Tboli households. They were used for meals, and may still be seen in some houses. At present, the Tboli ordinarily use tin and plastic plates or cheap china bought from the lowlanders’ sari-sari or variety stores. These antique plates, some of which are beautiful Ming dynasty pieces, are highly valued by the people and play an important role in the establishment of the bride-price. They are heirlooms acquired by Tboli ancestors through barter with lowlanders from Kiamba.

Not far from the hala, one usually sees a lihub, a round, wooden container carved out from a block of wood. It has a lid and is used for storing rice.

Anywhere near the surrounding area of the kohu, one may also see jawbones of wild boars, weapons used for hunting, and fish implements hooked onto the posts or against the sawali walls. The jawbones are kept as trophies of the number of wild boars they have captured. The weapons are usually inserted into the crevices of the sawali walls or beneath the cogon roof itself, far from the reach of the children.

One enters the Tboli house by way of the bakdol, through a trapdoor emerging from under the house and into the interior, as from a big chest with its lid open. The tikeb dol (lid to the entrance space), also called lingkob, is left open during the day. At night, it is lowered and closed just as one would a chest. Most houses make use of the aut, common bamboo ladder with rungs called slikan. The more traditional Tboli ladder, although now less commonly used, is a single bamboo pole with spaced, notched-off sections that serve as footholds. It is removed during the night so that no wild animals, enemies, or busawcan enter the house.

The fato kohu completes this end of the Tboli house, opposite the desyung, and is about 2 meters deep. The fato kohu is about 20 centimeters higher, just like the blaba and the desyung areas adjacent to the three sides of the lówó seel. The floor is made of lasak, laid crosswise.

The Tboli house has no toilet facilities but there is a kotol (outhouse) made of bamboo. For bathing, the Tboli go to the lakes and rivers.

To house guests during the moninum or marriage festivals, the gunu moninum, a huge structure, is built. The gunu moninum can accommodate hundreds of people. It is made of bamboo and sawali. While it looks like a giant gunu bong, its floor plan only retains the lówó or central space, around which the fringes are partitioned with light bamboo screens to mark out the sleeping spaces. Furthermore, unlike the gunu bong, its entrance is not through the floor but through a door built along one of its long sides. This long side opens into a square where the moninum festivities are held. At the other side of the square, the tabule, or structure bearing the contributions to the kimu by the host party’s relatives, is erected, framed by Tboli spears and bamboo poles.

There are other structures that the Tboli build. The lowig tnak is a shed constructed in the middle of the farm as shelter from the sun and the rain; it has a roof but no flooring. The hafo is a tall, skeletal tower built in the middle of the rice fields made of bamboo and thatch where the farmer or his children stand watch when the grain is ripe. The hafo is the control center of a bamboo clapper network devised to scare the birds away when they descend on the ripe grain. The watchers pull the strings of the clappers to rattle them. To store grain, a structure with proportions markedly different from the gunu bong is built. Although elevated from the ground as much as a gunu bong, the fol is smaller; its side walls are higher and windowless.

Today, many of the gunu and gunu bong are still standing; however, these have been modified by the use of metal and cement. The interiors hold modern furniture and décor. The Tboli village includes the barangay hall, playing courts, schools, churches, and the occasional Muslim telugan, also called torogan.

T'boli Traditional Attire

Video: THIS IS MINDANAO!! Catriona Gray National Costume

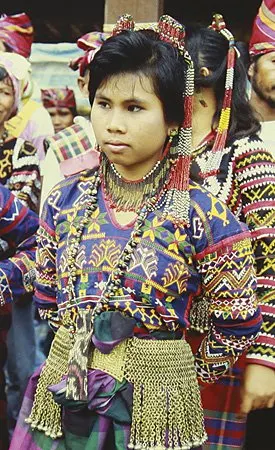

Among the many ethnic groups in the Philippines, the Tboli stand out for their marked and characteristic penchant for personal adornment. This is evident in their costumes, body ornaments, hairstyle, and cosmetic practices. According to Tboli belief, the gods created man and woman to look attractive so that they would be drawn to each other and procreate. At present, the Tboli have adapted to the lowlander’s attire, including fashion fads, but they still wear their traditional garments and accessories on special occasions.

Tboli women learn the skills of looking beautiful from an early age. It is not uncommon to see five- or six-year-old girls fully made-up, like their elder sisters and mothers. Eyebrows are plucked and painted, and a mtal hifi (beauty spot) is placed on one cheek. The face is powdered with a mix composed predominantly of lime, and the lips are enhanced in color from the fruit of a tree. Tboli women wear a traditional hairdo with the hair parted laterally along the axis of the ears. The hair along the front is allowed to fall in bangs over the woman’s brow, with some tufts allowed to hang loosely along the cheeks, and the rest pulled backward and tied into a bun at the nape. A suwat (comb) is stuck across the back of the woman’s head. Tboli women are not satisfied with one earring in each ear. The more earrings, the better. Thus, their ears are pierced not only on the lobes but also along the outer rim.

Tboli men and women regard white teeth as ugly, fit only for animals. Thus, the Tboli practice tamblang, in which they file their teeth into nihik or regular shapes, and blacken them with the sap of a wild tree bark, such as silob or olit. To indicate their wealth, prominent Tboli, such as a datu or his wife, adorn their teeth with gold, a practice adopted from the Muslims.

Tboli have themselves tattooed not just for vanity but because they believe tattoos glow after death and light the way into the next world. Men have their forearms and chests tattooed with bakong (stylized animal) and hakang (human) designs, or blata (fern) and ligo bed (zigzag) patterns. The women have their calves, forearms, and breasts tattooed in this manner. Another form of body decor is scarification, achieved by applying live coals onto the skin. The more scars a man has, the braver he is considered to be.

The Tboli woman has different attires for different occasions. While working in the fields, she wears a kgal taha soung, a plain black or navy blue long-sleeved collarless waist-length, tight-fitting blouse, with a luwek, an ankle-length tube skirt worn like a malong. For everyday wear, she has a choice of the kgal bengkas, a long-sleeved blouse open at the front, with 3-centimeter-wide red bands sewn crosswise onto the back and around the cuffs and upper sleeves; or the kgal nisif, a more elaborately decorated blouse, embroidered with cross-stitched animal or human designs, with geometric patterns rendered in red, white, and yellow, with bands of zigzag and other designs. She completes her wardrobe with a fan de, a skirt of red or black cloth, nowadays bought from the lowlanders. For formal wear, she has a kgal binsiwit, an embroidered blouse with 1 centimeter triangular shell spangles. This is matched by the tredyung, a black pinstripe linen skirt. The binsiwit is usually worn during weddings.

The Tboli use of body ornaments follows the idea that “more is better.” The woman wears several pairs of earrings at once. She has a choice of wearing the kawat, simple brass rings; the bketot, a round mirror, 1.5 centimeters in diameter, surrounded by small colored glass beads; the nomong, a chandelier-type earring consisting of 9 to 12 ten centimeter-long brass, interspersed with horsehair links with little clusters of multicolored glass beads at the end; and the bkoku, which is composed of 5-centimeter-long triangular pearly nautilus shells which dangle over the woman’s shoulders.

A characteristic ornament that stands out is the kowol or beklaw, a combination of earring and necklace. It consists of several strands of tiny, multicolored glass beads, suspended gracefully under the chin, from the left earlobe to the right. From the bottom strand of beads dangle about 7.5 centimeter-long black horsehair links with 2.5 centimeters brass links at each midsection and clusters of tiny, multicolored glass beads at the ends. These individual lengths of chain are suspended vertically, next to one another so that the jaws and chin of the woman appear to be framed by some delicate and exotic veil.

There are three types of necklaces: the hekef, a 3 centimeter-wide choker of red, white, and black beads, with occasional yellows; the lmimot, ranging in thickness from an adult’s thumb to a child’s wrist, and consisting of attached strands of red, white, and black glass beads; and the lieg, a necklace made of double- or triple-linked brass chains fringed with pea-size multicolored glass beads and hawkbells, often tasseled with more of the same. Most lieg are heirlooms passed from mother to daughter, and much valued.

The hilot (girdle) comes in several varieties. The ordinary hilot is a chain-mail belt with a width of 5 to 7 centimeters and 10 ccentimeters m lengths of chain dangling side by side along the entire lower edge of the belt. The front is adorned with two 5.7 centimeters square buckles entirely covered by characteristic Tboli designs. The hilot can weigh from 2 to 3 kilograms. To the ordinary hilot may be attached tnoyong (hawkbells) at the end of each dangling chain length. This makes the wearer swish and tinkle as she walks.

The hilot lmimot is different from the generic hilot in that it is made of solid, unremitting headwork in red, white, black, and yellow, rather than brass chain mail. Tnoyong finish off each of the 10 centimeters dangling strands of beads into a bravura of color and design.

There are two types of brass bracelets: the blonso, around 6 centimeters thick and 8 millimeters in diameter, 15 to 20 of which are loosely worn at the wrist; and the kala, thicker than the blonso and worn tightly, around five to an arm.

Like the bracelets, there are anklets that are worn tightly on the calves, like the 5 centimeters flat black bands called tugul. There are those which are worn loosely, called the singkil, of which there are three types: singkil linti, 10 centimeters in diameter and 6 to 10 millimeters thick with simple geometric ornamentation; singkil babat, a more ornately decorated version of the singkil linti, using cord and zigzag designs in high relief along the outer edge; and singkil sigulong, 15 millimeters thick but hollow and filled with tiny pebbles which make it rattle softly. Their external surface is decorated all over.

Tsing (rings) are worn in sets of five on each finger and toe, often with the brass rings alternated by carabao-horn rings. The rings can be plain or compound bands with simple triangular ornamentation.

Crowning the Tboli woman’s head are combs which come in several varieties, four of which are the suwat blakang, made of bamboo; suwat tembuku, a short comb decorated with a piece of mirror as the central decorative motif; suwat lmimot, a short comb decorated with colored glass beads; and suwat hanafak, made of brass. Aside from combs, Tboli women’s headgear include the kayab, a turban formerly made of abaca; but Tboli women have taken to wearing “Cannon” towels on their heads acquired from lowlanders’ sari-sari stores. In this item, no “traditional” colors are followed; they acquire the most wildly colorful towels.

For farmwork or traveling is worn the slaong kinibang, a round salakot (wide-brimmed hat) 50 centimeters in diameter, woven with bamboo strips and entirely covered by a geometric patchwork of red, white, and black cloth. Each hat is always unique and original. Underneath, the slaong kinibang is lined with red cloth that hangs down along the sides and back when worn to protect the wearer from the sun’s glare. Some slaong are decorated with two long bands of fancy headwork with horsehair tassels at the ends. Known as bangat slaong, these are worn on special occasions. The Tboli also weave baskets of many shapes and functions.

While the women retain much of their traditional costumes, Tboli men don their costumes only on special occasions. They ordinarily go about in shirts and trousers like any rural Filipino. Their traditional costume, which is made of abaca, consists of the kgal saro, a long-sleeved, tight-fitting collarless jacket; and the sawal taho, a knee- or ankle-length pair of pants, the waist section of which extends up to the shoulders, secured with an abaca band along the waist and made to fall, like a small skirt covering the hips and upper thighs.

The men’s headgear range from the simple olew (turban), to the slaong naf, a conical but very flat hat decorated with simple geometric designs in black and white, done on woven bamboo strips and topped by a fundu (decorative glass or brass knob). The slaong fenundo is less flat than the slaong naf, with a cross section resembling a squat tudor arch. It is made of straw-colored, even thread-thick, nito-like material sewn down in black and minute, even stitches. Part of the accoutrements of the Tboli male is the hilot from which his kfilan or sword is suspended. A datu often wears the angkul, a sash of thick cloth that is a mark of authority.

Tboli missile weapons are generally made of yantok (rattan) and bamboo, and tipped with tablos (brass) arrowheads or spearheads. While there are special applications for the different types of bows and spears, these are not usually decorated.

It is in their bladed weapons that the Tboli focus their decorative skills. The sudeng (swords) have long blades and hilts made of hardwood called bialong. The types of sudeng are the lanti, whose brass hilt is ornamented with geometric designs and 5 centimeters lengths of chain with tnoyong attached to their ends; the tedeng, which has no decoration; the kfilan, a bolo-like sword; and the tok, which, because of certain ritual associations, is the most decorated of Tboli sudeng. The tok has a 60 to 70 centimeters single-edged blade decorated with geometric designs, and a richly ornamented hilt with 5-centimeter lengths of chain attached to its edge, with hawkbells at their ends. The tok’s scabbard is made of wood held together by three to four metal bands. A geometric design is etched on the black surface, which is highlighted by the wood’s natural light color. Tboli kabaho (knives) are as richly decorated as the tok and come in a variety of shapes and sizes.

T'boli Arts and Crafts

The temwel, the Tboli metalcraft tradition, distinguishes Tboli culture and is linked to Ginton, the god of metalwork, who occupies a stellar place in the Tboli pantheon. The Tboli, however, give no indication of having ever possessed any knowledge of mining their own metals. Whatever metal there is to work on comes from scraps that the Tboli manage to get. Thus, in the case of brass or bronze, there are no standard alloy proportions. Copper was once obtained from one-centavo coins, while steel came from the springs of trucks abandoned along some highway in the lowlands.

The Tboli forge of gunu lumubon has afos lubon (bellows) made of bamboo cylinders 70 centimeters high and 15 centimeters in diameter, which have rattan pistons fitted with chicken feathers at the end of each piston head. Air comes from a 5-centimeter diameter bamboo section attached to the bottom of the afos lubon; held at the other end by the kotong lubon are stones that surround the furnace. The tau masool (smith) tempers the metal in this furnace and beats this with a solon (hammer) on a lendasan (anvil). After the initial forging, the blades are honed and polished with whetstones and further tempered over the fire. Once the basic blade is complete, it is decorated with brass or copper inlays or etched with geometric designs.

For artifacts with more intricate designs such as sword hilts, betel nut boxes, girdle buckles, anklets, and hawkbells, cire perdue or lost-wax method is used. Beeswax is applied over a clay core until the desired thickness—from 1 to 3 millimeters—is achieved. The designs of rows of uniform triangles, double spirals (s-shaped), cord bands, and other geometric figures are impressed on the wax original, while kneaded wax cords are attached in high relief onto their proper places in the overall design. Once completed, this snofut (model) is covered with fine clay, leaving only an outlet that flares out through the clay. This is left to dry and harden for five days, after which it is fired and the molten wax poured out through the outlet. Molten brass or bronze is then poured into this nifil (clay mold). The metal is then allowed to cool, after which the nifil is broken, revealing the finished artifact.

The third major area of Tboli metalwork consists of bracelets and solid anklets and the chain mail for the hilot worn by the women. This is made by drawing a superheated olo (raw bronze bar) through a gono hagalus (metal gradator) with holes of varying diameters to produce wires of different gauges, from the thick diameters of the blonso to the fine hilot chains. These wires are then wound around a bar corresponding to the diameter of the ornament desired.

A recent product of the metalwork tradition is the Tboli figurine. Still developed through cire perdue, these 7.5 to 10 centimeters statuettes portray Tboli men and women in their characteristic attires and engaged in typical chores.

T'boli Tnalak Weaving

Tboli weaving is another skill that has been raised to the level of art. Their traditional cloth, the tnalak, is made of krungon or kdungon (abaca fiber), especially the krungon libun (female abaca), extracted from the mature, fruit-bearing wild abaca. They identify four types of abaca: wogu (someone older than you); gindanao, which probably refers to “Maguindanao,” with its subtype lenewen, probably related to the lowlanders’ liniwan (fine pineapple fibers); luden (long); and genulon (banana-like). The Tboli do not mix different types of abaca fiber because the threads would break easily while they are being woven. Each fiber is carefully dried in the sun and stretched on the gono smoi, a comb-like wooden frame with teeth pointing up, to preserve the length and silkiness of each fiber.

After all of the fibers have been neatly smoothed out, they are transferred to the bed, a 50 to 400 centimeters bamboo frame, onto which they are evenly and closely spread, one just next to the other, as in a loom. These are held evenly in place by the tladai (wooden bar) laid across and directly over the fiber, which will be set in this exact position (in relation to one another) once the dyeing process has been finished, this being the warp of the cloth to be woven. It is while the fiber is evenly stretched on the bed that the traditional Tboli designs are knotted into them according to the tie-dye technique.

The areas of these fibers (warp) that must remain free from dye are covered with little individual lendek (knots), tied with separate pieces of thread treated with wax, so that when the woof is immersed in the dye, only the exposed parts are dyed. This lasts for weeks, as knot after knot is tied into place. Tboli women do not sketch or draw the design on the warp before them but merely follow a mental picture of a traditional design. Symmetry and distance are indicated and checked out in the process by the following measurements: dangaw, a hand span, from tip of thumb to tip of the little finger when extended; gulem sigu, a cubit, from middle finger to elbow; gulem imak, a yard, the distance between the armpit and the tip of the same arm’s middle finger; and difu, the span between the tips of the middle fingers of both extended arms. At the end of this stage, the fibers stretched on the bed look as if it were entirely covered by a tightly knit swarm of black ants. These are then removed from the frame for the actual dyeing.

Traditional Tboli tnalak has three colors: hulo (deep reddish brown), hitem (black), and bukay (white). A textile with only one or two colors is not a tnalak; a single-colored cloth is named by its color; a bi-colored cloth is called leggelis. All the reddish-brown and all the white sections of the design are protected within the innumerable individual knots, when the woof is boiled for the first time in earthen pots with black dye. Then, the set of knots on the sections meant to be reddish-brown (according to the pattern) are removed one by one, and the woof is dyed all over again, this time in red dye. The red dye does not alter the sections that have been previously dyed in black. The last step in the dyeing process, which might well last about three weeks, is the removal of the remaining set of knots which have all along protected the sections they covered from both the black and the red dyes. The creamy-white natural abaca color of these sections is left as is. The dyed fiber or warp is then given a final washing in the river.

The traditional vegetable dyes the Tboli use are colorfast. The material to be dyed black is simply boiled in water with the leaves and fruit of the knalum tree, and the material to be dyed red is similarly boiled in water with pieces of root or with the bark shavings of the loko tree. These dyes, the only two the Tboli know of, are permanent.

The dyed and dried fiber is now set on the gono mowol (backstrap loom) in the exact position that each fiber had occupied while stretched on the bed. The design is painstakingly dyed if it is to remain unaltered. One end of the gono mowol is hitched to a post or a wall in the house and kept taut by the weaver’s own weight as she reclines against a waist strap called a dlogong; this is slung onto the small of her back and attached to her end of the warp.

The width of the Tboli pieces of tnalak varies according to the reach of the individual wearer’s arm, as she sends the lungon (shuttle) from right to left and left to right, weaving in the wood. According to an unalterable tradition, the thread or woof fed by the lungon as it shuttles back and forth can only be black. Once the woof has been completely woven into the warp, the finished piece is rubbed with smaki (cuttlefish bone) into its final, evenly coruscating gloss.

The weaving of the tnalak piece usually takes about a couple of months or more. A longer time is necessary for putting together the kumo, the typical Tboli blankets that play an important role at the moninum or marriage festivals. These kumo consist of three pieces of finished woven material, their edges stitched together lengthwise, with the side bands framing the rich medley of Tboli designs at the center.

As is typical in all tie-dyed material, both sides of Tboli cloth can serve as the front. The designs are exactly the same, stitch for stitch, on either side. Tnalak, however, is best appreciated not in strong, harsh light but in the soft half-light so typical of Tboli house interiors, where the designs come to life and pulsate with esoteric messages.

The framework for tnalak designs is normally interlocking zigzags, triangles, rhombuses, hexagons, chevrons, and other geometric patterns. Within this framework are varying motifs: the kleng (crab), the saub, the kofi, and the gmayaw (bird-in-flight pattern); the tofi (frog); the klung (shield); the sawo (snakeskin); and the bangala (person within the home pattern).

Samples of Tboli decorative painting may be found in the lungon or coffin of dead Tboli. The paintings reveal the occupation of the deceased. If the deceased was a farmer, the lungon would be festooned with pictures of rice, camote, corn, and farm implements. If the deceased was a hulong kulo (poet), the lungon would be painted with representations of the moon and stars. If the deceased was a metalworker, one would find solon, sufit (pincers), lendasan, and fire among the designs.