The kundiman is a song written in triple time and usually begins in the minor key. It sings about a love that is faithful and true but carries a sad tone, highlighting the sacrifices the lover does for his or her beloved. There are three theories regarding the origin of the term kundiman. First, it was believed to be a contraction of the phrase kung hindi man (would it not be so). The second was that it might have been derived from the verse “Hele hele nang kandungan / Hele hele ng kundiman” (Hush, hush, the cradle / Hush, hush, the kundiman). Third, Norberto Romualdez and Consejo Cauayani (1954) opined that kundiman could refer to the red cloth worn by male dancers or men in the countryside. This theory is supported by the folk song popular in General Trias, Cavite, in 1873, “Mula nang Mauso, Damit na Kundiman” (Ever since the Cloth Kundiman Became a Fad):

Composer and music historian Antonio J. Molina said that the kundiman is closely related to its predecessors: the kumintang and awit (metrical romance). The accent is similar to that of the second beat of the second bar of the kumintang and the second beat of the sixth bar of the awit. Musically and textually, though, the kundiman represents some of the more significant facts of the Filipino psyche brought about by history and culture—sentimentality, sense of submissiveness, self-pity, yearning for freedom from want and deprivation, and the aspiration for a better future.

The evolution of the kundiman as a literary musical form and as an art song could be traced to three or four stages of development. The first was its purely functional phase—an expression of love through extemporized text with the insertion of certain phrase formulae, such as “kung hindi man.” The music was taken from preexisting tunes identified as awit and/or kumintang. The next stage was the semi-stylization of the musical formulae in which metric pulses of Western dances (valse, danza, fandango, etc.) were integrated into the singing style. Another stage would be the elevation of the previously extemporized text to a literary-poetic verse format by schooled writers, such as Patricio Mariano, Deogracias A. Rosario, Manuel Bernabe, and Jesus Balmori. While no longer relying on stock phrases, they nevertheless incorporated the principal thematic element in their texts—that is, the expression of unrequited and undying love, together with resignation to one’s final fate.

The final stage was the composition of the music to suit the structural and aesthetic demands of the poetic text. As developed by formally trained composers, such as Bonifacio Abdon, Francisco Santiago, and Nicanor S. Abelardo, the classical kundiman assumed the standard three-part form where the first two sections were in minor and related tonal areas and the final part was in the parallel major. The melodies were characterized by certain motivic formulae, such as the opening phrase starting on the upbeat, accenting on the second beat. Harmonically, the kundiman’s expression of uncertainty was portrayed through the various incomplete resolutions employed by composers such as Abelardo in the application of the chromatic harmony.

The era of the kundiman has been generally placed between 1800 to 1930. The year 1800 was alluded to in the folk song “Kundiman de 1800” (Kundiman of 1800) composed by Francisco Santiago, now popular among schoolchildren. The song’s serious mood was allegedly countered by its jocose lyrics when the printer of Emilia S. Reysio-Cruz’s collection of folk songs, which Santiago harmonized, pressured him to rush this particular piece. The three quatrains of this kundiman run as follows:

However, Molina stated that what could have been the true lyrics of this kundiman “as recalled by some older persons” were the following:

Contemporary composer and critic Felipe de Leon Jr. speculated that the pathos in the kundiman could be due to the Spanish practice of disallowing Filipinos from speaking about their love for country, and so they used the kundiman as a subtler medium for their nationalistic expressions. Hence the kundiman not only expresses the lofty sentiment of love but also of heroism. The kundiman “Jocelynang Baliwag” (Jocelyna of Baliwag), for example, originally dedicated to Jocelyna (Pepita) Tiongson of Baliuag, Bulacan, really addressed a bigger muse—Mother Country. It inspired many a Katipunero (Filipino revolutionary) to fight for freedom from Spain, and was called the “Kundiman ng Himagsikan” (Kundiman of the Revolution). The lyrics of this kundiman run as follows:

In the early decades of the 20th century, Francisco Santiago stylized the kundiman, elevating it to a higher creative plane as he fashioned a simple folk song into an appealing art song. He developed the kundiman song into national classics whose melody, text, and harmony were intertwined.

Santiago is credited with giving the kundiman a ternary or three-part form, taking it beyond its simple unitary song form. His first kundiman was “Kundiman,” also known as “Anak-Dalita” (Child of Woe), 1917, with Tagalog lyrics by Deogracias A. Rosario and Spanish text by Jesus Balmori. Other important kundiman of Santiago were “Pakiusap” (Plea) and “Madaling-Araw” (Dawn).

The kundiman that were later written by Nicanor S. Abelardo were believed to have been inspired by Santiago’s. Abelardo created some of the most famous artistic kundiman—among them, “Mutya ng Pasig” (Muse of Pasig), “Nasaan Ka Irog?” (Where Are You My Love?), and “Kundiman ng Luha” (Kundiman of Tears). In 1920, Bonifacio Abdon composed “Kundiman,” also known as “Kundiman ni Abdon” (Abdon’s Kundiman). Abdon was then the director of the Asociacion Musical de Filipinas, which sponsored the concert of Russian cellist Boguomil Sykora, who wanted to conduct a native composition. Abdon wrote the kundiman, with text by his brother-in-law, Patricio Mariano. It was sung for the first time by a choir. Other famous kundiman were Francisco Buencamino’s “Ang Una Kong Pag-ibig” (My First Love) and Constancio de Guzman’s “Bayan Ko” (My Country) with lyrics by Jose Corazon de Jesus. “Bayan Ko,” originally a song protesting American colonization, became the anthem of the parliament of the streets during the Marcos dictatorship.

In the pre-World War II era, the kundiman was composed to honor heroes on their birth or death anniversaries, to congratulate women on their birthdays and graduations as professionals, and as theme songs for films and organizations. Actively composing kundiman during this period were composers Castro Emiliano, Pedro Santos Gatmaitan, Gerardo Enriquez, Saturnino E. Villanueva, Facundo Perez, Dominador Rivera, Cornelio Lacsamana, Francisco Perez, Ariston Avelino, Lucino Sacramento, and Liberato Esguerra. The lyrics of these songs were provided by the composers themselves or by collaborating lyricists, among whom were Jose Katindig, Pio Ramirez, Maria M. Villanueva, Deogracias Rod. Gonzales, Florentino Ballecer, Juan Hernandez, Leoncio Reyes, Filomeno Alcaraz, and Jose Dal’ Estrella.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the kundiman was used by sarsuwela composers for their love songs. Leon Ignacio created the “Kundiman ni Angelita” (Kundiman of Angelita) for Dalagang Bukid (Country Maiden). In the late 1930s and in the decades after World War II, Filipino film musicals, which were really filmed sarsuwela, either used famous kundiman as title and theme songs—for example, Pakiusap, 1940—or commissioned composers to create new kundiman for the movies. Composers for the movies include Constancio de Guzman, Santiago Suarez, and Juan Silos Jr.

In the postwar era, the term kundiman has been used to mean not only a specific musico-literary form but also a style and a particular musical sentiment. As late as the 1960s, the classical kundiman formats were still employed by such composers as Lucio D. San Pedro in his “Sa Simula Ako’y Labong” (In the Beginning I Was a Bamboo Shoot), Felipe Padilla de Leon in his “Ganyan ang Pagsimba” (That Is How to Go to Church), Rosendo Santos in his “Kundiman ng Puso” (Kundiman of the Heart) and “Pighati” (Grief), and Alfredo S. Buenaventura in his “Huling Hibik ng Pilipinas” (Last Cry of the Philippines). In the second half of the 20th century, kundiman sentiment was felt in the romantic ballads of George Canseco, Leopoldo Silos, Ernani Cuenco, and Restie Umali. Current additions to the kundiman repertoire include Angel Peña’s “Sa Batis ng Ligaya” (In the Stream of Happiness), Noel Velasco’s “Mutya ng Mayon” (Muse of Mayon), Michael Dadap’s “Walang Paalam” (No Goodbye), and Joey Ayala’s “Walang Hanggang Paalam” (Never-ending Goodbye).

There has been a proliferation of recordings of kundiman in different forms in the Philippines and abroad in the 21st century. Raul Sunico’s multivolume Classic Philippine Sentiments: A Keyboard Treasury of Love Songs and Folksongs contains many kundiman arranged for solo piano. The series is made up of several albums, which include Katakataka (Surpising), Cavatina, Lambingan (Romance), Balikbayan (Filipino Returnee), and Pahimakas (Farewell). In Alaala (Memories), Sunico also devoted a complete album to the kundiman of Nicanor Abelardo. The centennial album Mga Awit ng Himagsikan 1896-1898 (Songs of the Revolution 1896-1898), 1998, was a special recording of songs of the 1896-1998 Philippine Revolution, many of which have been considered written in the kundiman form. The songs were arranged by Raul Sunico and sung by the Philippine Madrigal Singers, with Lester D. Demetillo on guitar and Antonio R. Maigue on flute. In 2007, the Berlin-based duo made up of baritone Jonathan de la Paz Zaens and pianist Abelardo Galang II recorded and released an album titled Kundiman: Philippine Art Songs in Germany, the land where the genre flourished in the 19th century. Joey Ayala’s two modern kundiman, “Kundiman sa Ulap” (Kundiman in the Clouds) and “Walang Hanggang Paalam” (Endless Farewell) were part of his album 16 Love Songs. Basil Valdez released The Filipino Classics, 2006, a collection of classic Filipino songs from the 1920s to the 1960s arranged by Ryan Cayabyab. The album featured the San Miguel Philharmonic Orchestra, which was conducted by Cayabyab.

In 1991, in an effort to generate a broader appreciation of kundiman, Hotel Nikko Manila Garden in Makati initiated the singing competition called “Kundiman Fiesta” to revive the singing of the Filipino kundiman and popularize this singing tradition among the youth. The first five years produced the following top kundiman singers: Francisco Batomalaque, 1991; Alexis Sumicat, 1992; Nolito Gregorio, 1993; Joel Saavedra, 1994; and Cherry Batalla, 1995. Due to a change in the hotel’s ownership in 1996, the annual fiesta faced an uncertain fate. The National Commission for Culture and the Arts eventually took over, and the 1996 edition was held on 4 Dec at the Folk Arts Theater, with Marya Deeda Barreto emerging as the winner. In 1995, another kundiman singing competition was started, this time by the Makati Coliseum and Cultural Affairs Office, to celebrate “Buwan ng Wika” (National Language Month) in the city. The competition, initially called “Kampeon ng Kundiman” (Kundiman Champion) and later renamed “Kundiman sa Makati” (Kundiman in Makati), has been held annually since.

Folk Song / Folk Music or Awiting Bayan

A folk song is a song that has been handed down orally through generations, usually in a set melody; is extemporaneously composed; and expresses emotions, thoughts, or ideas shared by the community. It is called awiting bayan in Tagalog, ambahan/awit/biyao in Cebuano, susunan in Manobo and Bukidnon or the more melodious iringay in Bukidnon, badio in Ibaloy, leleng in Sama Dilaut (Badjao), and balikata in Tiruray. The copla in Capiznon or Ilonggo is the generic term for the light song, such as the lullaby, game song, work song, or nursery song. The Ivatan have the laji, which is a lyric folk song. The Dulangan Manobo have the duyuy, varieties of which include the duyuy nga traki or narrative song, the duyuy nga oy-oy or nursery song, and the duyuy nga iniwanen or dirge (Cruz-Lucero 2007, 179).

The folk song’s exact origin or authorship is, by and large, lost or forgotten over time, as it goes through the process of oral transmission. While the melody tends to remain constant, the lyrics can vary over the years. Indeed, it has no original text, being freshly created by successive singers as they make their own versions (Wells 1950, 5).

Folk songs do not always originate from the masses. Many songs that start out as art songs become folk songs, undergoing alterations in lyrics or music by singers who learn and transmit them orally. Folk songs, which are part of every phase of life of the Filipino, can be classified into the narrative and the nonnarrative. Narrative songs, also called ballads, are those that tell a story. Nonnarrative songs are more varied, because they pertain to different stages, concerns, and activities in the life of a person or community.

The Narrative

The narrative song or ballad, which tells a story, is usually sung to a repeated melody. It is orally learned from the lips of others or extemporaneously composed. It usually concentrates on a single event or episode and uses a dramatic method of narration, which results in brevity and compression. The narrator generally shows an impersonal attitude. Other conventions of the ballad are the use of refrain, incremental repetition, and stereotyped words and phrases. The ballad is called komposo in Aklanon, Capiznon, Cuyunon, and Ilonggo; ullalim in Kalinga; gassumbi in northern Kalinga; nahana in Yakan; idangdang in Manobo and Bukidnon; the uman in Subanon; saliada in Mansaka; and tenes-tenes in Sama Dilaut (Badjao). Other types of narrative songs are the Kankanaey day-eng, which tells a legend or fable; the Ifugao alim, which is chanted by the rich during a prestige ritual; the Bontok allayo, which is the history of the sponsoring family in a prestige ritual; the Blaan flalok to sawa, which is the story of people and place-names; the Blaan flalok dawada, which consists of four short legends; the Tausug liangkit, which is about love, war, nature, and so on; the Tausug lelling, which relates and comments on current events; the Yakan kata-kata, which is about people in earlier times; and the Yakan jamiluddin, which tells a love story. The Sama Dilaut kata-kata, which is about the travails of heroes, is also sung in the hopes of healing the sick (Nimmo 2001, 197-98).

Narrative songs of adventure are the Mandaya bayok, about the cycle of life and death, sacrifice, suffering, and joy (Sillada 2013); the Blaan tamfang, about the war exploits of the war hero named Tamfang; the Manobo bimbiya, about the adventures of a folk hero; the Manobo kirenteken, which are historical legends about the Kirenteken Manobo; the Manobo mandagan, which are historical tales; and the Tiruray binuaya, about great events in the distant past. Ballads tend to be leisurely in narrative style, detailed, and moralistic in tone.

|

| Maranao performing the bayok (Ramon A. Obusan Collection) |

One of the oldest ballads of the Tagalog may well be “Tamuneneng” (Beloved), in which the singer narrates the whereabouts of the woman he loves, and how he longs to see her again. A popular ballad is the Tagalog “Ang Bangkero” and the Kapampangan “Ing Bangkeru” (The Boatman), a didactic song that narrates how a proud and pedantic college student is humbled by a lowly boatman. It ends with a moral: those who have academic learning should not brag about it, because they may encounter a simple person who is more knowledgeable about the practical things in life.

Other Tagalog ballads are religious in character, pointing out the sinfulness of disrespect to parents and to religion, as in the song “Donya Marcela,” and the virtue of charity and almsgiving, as in the song “Tulang Pang-Todos los Santos” (A Poem for All Saints’ Day). A well-known Tagalog song, whose original verses from the Spanish period are lost, is “Doon Po sa Amin” (In Our Town), which tells about a place called San Roque, noted for its four interesting beggars: the blind one sees, the crippled one dances, the deaf listens, and the mute one sings. The Tagalog wedding song “Matrimonyo” (Matrimony) may be a blend of the narrative and nonnarrative, because it does not simply tell one story from beginning to end, but also gives religious instruction and advice to the bride and groom.

The komposo in the islands of Panay and Negros Occidental narrate tragic love affairs and domestic tragedies. Many are about historical or sensational events, such as executions, calamities and disasters, and wartime bombings. The violent earthquake of 1948, for instance, is the topic of one Ilonggo ballad. “Montor” is about the execution and last words of a man who ransacked a convent and then was captured by the Americans. Two other versions identify Montor either as a Moro or a captain during the early years of American rule. In both versions he is said to be a notorious bandit. This seems to be an offshoot of the American propaganda during that period that Filipinos who participated in the resistance war against the Americans were tulisanes (bandits). A komposo about a witch named Basilio may have some basis in fact because it tells of how he has eaten his infant daughter because of his extreme hunger, and his wife reproaches him by reminding him that they have weathered periods of famine before.

The outbreak of the Pacific War occasioned many komposo. These war ballads recount the hardships suffered by the people during the Japanese occupation. The people were dressed in sacks and used leaves as sleeping mats, went one ballad. The heroic exploits of Filipino pilots, as in “Deocampo kag Villamor” (Deocampo and Villamor), and the return of General Douglas MacArthur to the Philippines became the subject of songs.

A peculiar type of ballad has plants and animals as characters mimicking human activities. They hold meetings, elections, and even gambling sessions. In one Tagalog song, “Ang Pulong ng mga Isda” (The Meeting of Fishes), the king turtle presides over a gathering of fishes, where the kandule (sea catfish) is a priest, the lapu-lapu (grouper) is archbishop, and the tiny dilis (anchovy) is a police officer. The Cebuano ballad “Hantak sa Kalanggaman” (Gambling among the Birds) narrates a gambling session among the feathered creatures. Another ballad about a fiesta in Kanlinao tells how a musical band of animals plays their instruments at a dance, with eels playing the clarinets, the turtle the drums, the lizard the saxophone, and so on. One Pangasinan song enumerates various fishes and water-dwelling creatures—pantat, ayungin, alalo, siwisiwi, bulasi, patang, and bisukol—and describes their swimming habits. All these songs about plants and animals are apparently intended for children, because they are both humorous and educational, each song reading like a catalog of fishes, birds, animals, or vegetables, which facilitate a child’s familiarization with the natural world.

A narrative song is sometimes performed to communicate with a deity. In “Dugidma,” a Mandaya bayok, a woman prays to a goddess to help her dispel the rumors about her shabby physical appearance and dishonor that torment her. She asks for mercy and makes a plea that her tooth necklace be buried with her when she dies, and that those who have wronged her should be punished (Fuentes and dela Cruz 1980, 27-29).

Narrative songs can also be didactic. In “Kalangan,” a Yakan song, a diver named Ahari gathers poisonous sea roots while hunting for food; a fish leaps into his throat and spoils his search, leaving him in prayer (Eugenio 1996).

Some ballads about lovers are also composed in narrative. The Maranao’s “Mamayog Aken” is about the couple Mamayog and Ogarinan. Ogarinan asks Mamayog where he is going, and he tells her that he is going to the neighbor’s to look for a living. Ogarinan suspects that Mamayog will cross the river to meet the Datu’s daughter whom he admires. Mamayog calms Ogarinan, but she swears to use her kris should she catch him being unfaithful (Eugenio 1996).

Then there are narrative songs with unique features. The tenes-tenes, when sung by a highly skilled performer, is a sprawling narrative sung during weddings or circumcisions and other occasions; the ballad conveys heroic adventures and can hold the audience captive for one to two hours. When sung by children or adolescents to pass time, the tenes-tenes begins with the singer ascribing the song with a color, which depends on the singer’s mood or intent (Nimmo 2001, 188-91).

The Nonnarrative Song

This type of folk song may be classified into the following subtypes: life cycle songs, including those related to infancy, childhood, courtship, wedding, family life, death, and mourning; occupational and activity songs, such as drinking songs, boat or rowing songs; agricultural songs; ritual and religious songs; and miscellaneous songs, such as songs about nature, and humorous songs.

|

A mother singing a lullaby to put her baby to sleep as illustrated by Nestor Leynes’s Mag-ina sa Banig, 1960 (Paulino and Hetty Que Collection)

|

The lullaby is called oyayi by the Tagalog; ili-ili or ili by the people of Panay and Negros; duayya by the Ilocano; wiyawi or wig-usi by the Kalinga; cansiones para ammakaturug by the Ibanag; baliwaway by the Isinay and Ilongot; angngiduduc by the Gaddang; almalanga by the Blaan; sandaw by the Cuyunon; buwa, tategdil, linupapay, and abenaben by the Subanon; balikata bae by the Tiruray; yaya by the Yakan; oyog-oyog by the Mandaya; the langan bata’bata by the Tausug; binua by the Sama Dilaut (Nimmo 2001, 185-86); and adang by the Aeta. It is a song sung to hush babies as they are tenderly rocked to sleep in the mother’s or father’s arms or in the cradle. As such, they have a soporific tune, sometimes with repetitious text. The lyrics reveal something about the nature of family life and the immediate world about. One sad lullaby found across regions tells of either parent or both parents having to be away to look for food. Here is the Gaddang version.

Aru, aru, maturug y adu

Se innang y inam so battung

Innang namanuet si aralu

Ta wara na ilutu.

(Lull, lull, sleep, my boy,

For your mother has gone to the creek,

She went to catch a lot of perch

So there’ll be food to cook.)

Some lullabies can be complex portraits of life as lived by the common folk. In one Tagalog song, a mother expresses her feelings about their impoverished situation, and admonishes her child to be good:

Sanggol kong anak, anak na giliw

Matulog ka nang mahimbing

Marami akong gagawin

Huwag mo akong abalahin

Iyang duyang hinihigan

Banig mo’t lampin ay gutay

Tayo’y mahirap na tunay

Luha at hapis ang yaman

Kung lumaki’t magkaisip

Ikaw bunso’y magpabait

Mag-aaral na masakit

Ng kabanalang malinis.

(Sleep, my beloved child

Sleep soundly now

I have much work to do

So you mustn’t disturb me

Your cradle, mat, and diaper

Are all in tatters

Because we’re so poor

And are rich in grief and tears

When you grow up and mature

May you stay good, my child

Take pains that you may learn

The ways of holiness.)

It is in this tradition that contemporary lullabies, whose authors are identified, seem to have been composed. The tune has become both soporific and melancholy, and the lyrics express two kinds of feelings: sadness over the present state of things and the absence of a parent, but also hope for a better tomorrow. In Jesus Manuel Santiago’s “Meme Na, Aking Bunso” (Sleep Now, My Youngest One), probably the best-known Tagalog lullaby in recent years, there is the element of protest against the social conflicts that keep loved ones apart. “Lingon,” a Blaan nursery song, tells of a mother who sings about her regret over losing a beloved musical instrument, a symbol for coming of age and, consequently, the loss of innocence.

The oyog-oyog of the Mandaya celebrates childhood and parental love and usually speaks of a person’s resolve to become virtuous despite adversity (Fuentes and Dela Cruz 1980, 23). The typical oyog-oyog are rhyming, often heptasyllabic couplets about the affection of parents for their children. The singer takes a breath between each line, while maintaining a soft, but fluid tone. Words or phrases are repeated to establish a pattern or melody.

For the Sama Dilaut, the nursing song becomes a medium for expressing matters that would otherwise be prohibited in ordinary speech. While the mother sings the binua typically to soothe an infant, the song also enables her to air her grievances about domestic affairs or her relationship with in-laws. Neighbors overhear her singing and sympathize with her (Nimmo 2001, 185-86).

Songs of childhood and growing up take us to the happy and carefree world of the child—a world of fun and games, of jokes and laughter, with much time spent outdoors in climbing trees and picking fruits, as in the all-time favorite “Leron, Leron Sinta” (Leron, Leron Beloved). In this juvenile world, rural poverty is mitigated by another kind of wealth. In the song “Bahay Kubo” (Nipa Hut), the child describes not a squalid squatter dwelling but a neat little house of thatch and bamboo set amidst a garden planted with many kinds of nutritious vegetables.

The child’s closeness to nature is expressed in songs in which he mimics the movements of crabs, as in “Dondonay,” or “Pakitong-kitong,” and talks to birds, as in “Taringting,” the moon, or other elements in nature.

Many children’s songs are sung to accompany their play activities. Such are their counting songs, as in “Isa, Dalawa, Tatlo” (One, Two, Three); clapping songs; songs enumerating the months of the year, as in “Lubilubi”; and songs sung while the children play hide-and-seek and other games.

Children’s songs are called cansiones para abbing by the Ibanag, ida-ida wata by the Maranao, langan batabata by the Tausug, sanggubanan and sandimun by the Subanon, and lia-lia by the Sama Dilaut. Subanon children also sing the abenaben, which is typically a lullaby, to share jokes with playmates (Aleo et al. 2002, 265). During the wedding ritual (called chono), small Bontok boys sing the aygaen and older children sing the orakyo, which is about how the sacrificial carabao for the chono ritual is caught and slaughtered.

Though children’s songs mostly convey playfulness and gaiety, some function as a means for children to negotiate emotional ties with adults. Sama Dilaut children sing freely about their anger toward playmates or elders through the lia-lia, which is sometimes known as the “spite song.” Children may get punished for criticizing adults, but songs provide a socially acceptable means for them to express frustration (Nimmo 2001, 186-87).

Bontok boys sing the bagbagto as they engage in a mock battle using stones as weapons. Manobo children have a song called bakbak, which is about the frog; older children sing the binlay pa biya-aw for their younger sibling.

Maguindanaon children sing “O! Apo, O! Apo,” about a grandfather who avenges a princess bitten by a crocodile. “Taga Snolon” (From Snolon), which is sung by Tboli children, describes proper hygiene and grooming as an early preparation for married life. “Patedil” from the Tboli is a song about the beauty of a kingfisher. Maranao children sing “Pokpok Alimpako,” an accompaniment to a game in which they sit in a circle and place their fists one on top of another, mimicking a pounding motion while singing, and repeating the song once the lowermost fist is released (Eugenio 1996, 129-30).

Love songs constitute the biggest group of Philippine folk songs. They are called dawot by the Mandaya, which is sung by two lovers to each other (Sillada 2013), and Maranao; pinatalatto cu ta futu cao (literally, “pondering within my heart”) by the Ibanag; ayegka by the Bontok; mandata by the Manobo and Bukidnon; kulilal for the contemporary form and lantigi for the ancient form by the Palawan; dionli by the Subanon; and lendugan by the Tiruray. The Capiznon, Aklanon, or Ilonggo panawagon is a song about unrequited love and is more plaintive than the balitaw, also a variety of love song. The serenade is called harana by the several ethnic groups and tapat by the Ilocano. The aliri is an Aeta improvisational courting song. The Yakan’s courting songs are the kalangan, lunsey, and lembukayu. The Tagalog courting poem is called the diona.

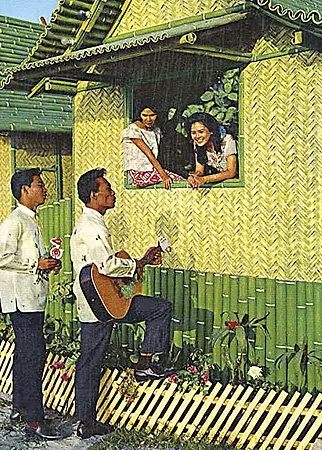

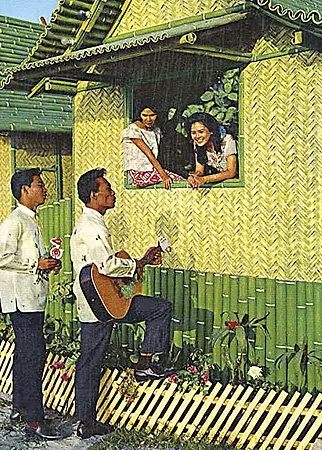

|

| Harana, a custom where men sing love songs to serenade a woman (Photo courtesy of Pascal Rossette) |

Many of these love songs are paeans to the proverbial qualities of the Filipino woman. There are songs about “Taga-Bicol” (One Coming from Bicol), “Daragang Taga-Cuyo” (Maiden of Cuyo), “Dalagang Pilipina” (Filipino Maiden), and “Lulay.” Invariably, they describe the qualities of the ideal Filipina. She is “parang tala sa umaga”

(beautiful as the morning star), “bulaklak na tanging marilag” (a flower of exceptional beauty), “batis ng ligaya at galak” (a wellspring of joy and happiness), “ligaya ng buhay” (the delight of life), “ilaw ng tahanan” (the light of the home), “bulaklak ng lahi” (the flower of the race), or “dangal nitong bayan” (the honor of the country). In Pangasinan, she is “malimgas” (beautiful and pure). One Cebuano song reveals how much rural maidens prize chastity: touch Inday and she will not stop crying until you marry her (Eugenio 1996).

The relations between man and woman are a common theme in songs of love and courtship. There are songs advising young, unmarried women to be careful in their dealings with men. Typical is a Tagalog song “Bubuyog at Bulaklak” (Bees and Flowers), which warns maidens against the deceptions of men, who are compared to bees hungry for a flower’s nectar and who fly away laughing at their victims.

In the Capiznon “Sang Dyutay Pa Ako” (When I Was a Small Girl), a woman whom a young man did not pay attention to when she was small and attracted to him, now sets the terms of the relationship. She will accept his suit only when impossible conditions are met—when stone softens and water hardens, when the mountains recede and the plains rise to the sky (Eugenio 1996, 246).

There are also songs that attest to love persisting in the face of change. The Sama “Magbangkah-bangkah” (Boating) tells of a fisherman who, no matter where the wild currents take him, carries his beloved’s name on his lips. The Tausug “Hanugun, Hahugun” counsels that love is not lost even in a time of grief (Eugenio 1996, 284).

“Muyin Paru Ñinu” (Whose Face Do I Behold?), an Ivatan laji, frames desire and death in the primal act of eating and drinking. The lover requests the beloved not to bury him under “the Cross of San Felix” when he dies but under the beloved’s own fingernails. This way, the beloved shall still partake of the lover whenever she eats or drinks (Evasco 2003, 83-84).

Courtship, as portrayed in songs, is an arduous undertaking for a young man mainly because the ideal Filipino maiden is so difficult to woo, win, and wed. Moreover, custom requires that the young man seek the permission of the girl’s parents before he starts courting the woman, as one song states. Suitors can make the most extravagant promises to their objects of desire; thus, the Kapampangan lover offers to make the girl happy by stringing stars to make her a necklace and by cutting the moon in half to make a crown for her head. A Pangasinan swain offers to cover with a handkerchief the floor his lady love steps on.

During the period of courtship, menfolk resort to serenading the women. Some of the most beautiful love songs, in the form of the danza or the kundiman, were sung in serenades, which are hardly practiced today. At the height of this courtship custom, hyperbole would be the favorite stylistic device to win the sympathy of the girl, luring her to look out of her window. In one song, the lover claims that in his sleep, he lies down on his mat of flowing tears, and rests his head on a pillow of sadness. In another song, he would swear that he is about to become a cold corpse, so he begs the beloved to open her window, which portends the bliss of heaven’s gate opening. The lover would offer to die for the sake of his love, should the woman wish it.

The longest recorded wedding song is the Tagalog “Matrimonyo” (Matrimony), which is from Bulacan. In the song, newlyweds are advised to treasure their marriage and to take as their models Joseph and Mary as well as the pious Abraham and his wife Sarah. Short wedding songs among the Tagalog and Bikol are sad in tone and give a gloomy picture of married life for the woman. She has to give up all her friends, forsake all her former pleasures, and concentrate on pleasing her husband lest she displease him and get beaten up. It is a gruesome fate forecast for the bride.

In contrast, in the “Dindinay” from Bukidnon, the parents are happy at the union of their children. The song is cheerful and optimistic about the fate of the newly wedded couple and underscores the important role that elders play in guiding the couple into prosperity and happiness (Eugenio 1996, 425).

Numerous folk songs are about the rejection of a suitor. Songs from Southern Leyte, such as “Pagmahay” (Disheartened), “Walog sa mga Luha” (Valley of Tears), “Carmeling,” “Pagkalaay” (How Boring), “Pangandoy Ko Ikaw” (You Are My Yearning), “Pagkalaut” (How Miserable), “Lantawa da Ako” (Look At Me), and “Kaniadto Ra” (Long Before), lament unrequited love, rejection, or betrayal, and are often sung by balladeers in a style that mimics the sound of weeping (Go-Saga 2010, 72-87).

“Dandansoy,” a Hiligaynon song, describes the parting of lovers. In one version, the woman returns to her home in Payao, leaving behind her beloved Dandansoy. She instructs him not to bring water should he decide to follow her; instead, she tells him to dig a well by the road. The woman reveals that Dandansoy has been unfaithful, a fact which explains the cruel terms on which they are parting (Eugenio 1996, 390). In another version of the song, the singer expresses yearning for the beloved who had to leave for a faraway place. This version is popular in Iloilo, a province known for sending the most number of maritime workers abroad, and in Antique where many men leave their families to work as laborers in sugar mills in Negros Occidental (Villareal 1997, 88-89). The Tausug “In Katulak pa Minis” also has the motif of parting lovers. This time, a man leaves a woman as he sails for Minis Island (Eugenio 1996, 394).

Songs dealing with family life express Filipino ideals about the structure of the family, the respective roles of parents and children, and the emotions that bond the family together. Songs of advice are the Isinay anino and the Bukidnon idangdang. Sung specifically as advice to newlyweds are the Ilocano dallot and the Yakan sa-il. The Tiruray meka-meka is a wife’s song of loyalty to her husband. In a Pangasinan song, the bride’s parents bid her farewell on the eve of her wedding.

As expressed in a Bikol song, the ideal family can be likened to a tree. The father is the trunk, the mother is the branch, and the brothers and sisters are the fruit. Mutual love between parents and children is expressed in the song “Pinalangga Ko” (My Loved One), in which a child sings about basking in the love and care of her parents. In the song “Si Nanay, Si Tatay, Di Co Babayaan” (Mother, Father I’ll Never Neglect), the child sings of love and gratitude, and vows always to look after the parents. “Didto sa Layong Bukid” (In That Distant Mountain), a song from Southern Leyte, describes the daily routine of a poor family living on a mountain, reclaiming in the end their dignity with a declaration that poverty has not quelled their will to live (Go-Saga 2010, 88-89).

Debates in verse and music, usually pitting men and women against each other, are performed on special occasions, such as courtship, marriage negotiations, weddings, wakes, and sacrificial rituals. Kankanaey men and women engage in the daing during the performance of a solemn sacrifice, the dayyakus during sacrificial rituals performed by the headhunter, and the ayugga, which has a quicker tempo. In the Ibanag kinantaran, the man takes the name of Pepe and the woman that of Neneng. The kakanap is a question-and-answer game song between two Aeta. The Kankanaey daday occurs between the village women and a female outsider who has come to marry a village member.

The dilot and kopla from Panay and Negros are dialogue songs, used by singers to express their feelings through metaphors. A balitaw is a duet where the woman responds to the man’s serenading (Villareal 1997, 92-93). The Manobo masulanti is a song dialogue between a mother, her daughter, and the young men at a wake. The Ilocano dallot is a song-and-dance joust. The Tausug have the sindil; the Yakan have the maglebu-lebu seputangan, which is between a group of men and a group of women.

There are songs that enable communication among elder members of the community, among men and women, and among locals and visitors. Among the Subanon, the epic song inadung is a means for elders to converse during gatherings, occasions, or hosting visitors. Subanon women sing the sinalig also as a way to engage in conversation, if not to praise Asug or God. Wedding engagements are set by men performing the song to women.

The adaptable sandidi, like the belumin and the biayen, is a song of praise, but it can also be sung as a lullaby or as a means for arbiters to intervene in disputes. Other conversational Subanon songs are the sambugaway, the peniligan, the sandugan, and the libudu’ (Aleo et al. 2002, 260-63).

When a loved one dies, songs may be sung during the wake, either by members of the family or relatives and friends keeping vigil and paying their last respects to the departed. Parlor games are also usual on such occasions. A Tagalog song tells those playing games during a wake not to make too much noise, and to pray instead for the soul of the dead person.

In the Ilocos region and in the Mountain Province, the songs are addressed less to the living than to the dead, and discuss more about family matters left behind. In the West Bontok “Baya-o” (Brother-in-Law), a man sings the song for his brother-in-law as a duty of a member of the family. Dirges are the Bontok annako and pagpaguy, the Kankanaey soso, the Kalinga ibi, the Ilocano dung-aw, the Aeta ingalu, the Cebuano kanogon, the Manobo and Bukidnon minudar and mauley, and the Tausug baat caallaw. The Subanon have a dirge for their chief, called the giloy. The Kankanaey sing the dasay when someone is dying. The Aeta talinhagan expresses the last words and wishes of the dying. Sung eulogies are the southern Kalinga dandannag, lbaloy dujung, Ifugao alim, Bontok achog, and Manobo mahudlay and ay dingding.

In Southern Leyte, the kulisisi or kulasisi is performed as entertainment during wakes, particularly for the grieving family. It consists of riddles, jokes, puns, games, tongue-twisting songs, and poetic jousts. Players squat on the floor in a circle and assume roles as members of a royal court. An expert of the game serves as “King” who begins by declaring, “Kulisising Hari, Kulisising Magsabat!” The activity later grew into a full debate where controversial subjects are taken up (Go-Saga 2010, 149-91).

Work and activity songs present an interesting variety of traditional occupations and activities Filipino folk engage in—farming, sharecropping, barbering, dancing, embroidery, rowing and fishing, hunting, pottery making, salt making, dressmaking, tailoring, stevedoring, tuba gathering, woodcutting, and wooden-shoe making. Expectedly, the greatest number of occupational songs is about farming, a fact that reflects the predominantly agricultural economy and life of the country. The most popular of songs related to farming is “Magtanim Ay Di Biro” (Planting Rice Is No Joke). Fishers may still sing the rowing songs of their ancestors, later the Tagalog soliranin or the kalusan, a rowing song still alive among the Ivatan fishers of the stormy Batanes sea. The kalusan is also sung by farmers clearing their land. Ivatan woodcutters also used to accompany the sawing and hauling of wood with a rhythmic song that, as in rowing, synchronized movement and enlivened the collective spirit. Working songs are called hila/hele/hololhia in Cebuano, ayoweng/mangayuweng in Bontok, baat in Tausug, and delinday in Manobo and Bukidnon. The saloma is the Cebuano sailor song; the talindaw is the Tagalog boat song.

|

Depiction of Tagalog natives pounding rice (Les Philippines: Histoire, Geographie, Moeurs, Agriculture, Industrie et Commerce des Colonies Espagnoles dans l’Oceanie by Jean Mallat. A. Bertrand, 1846)

|

Rice-pounding songs are the mambayu in Kalinga and chay-assalkwella/kudya in Bontok. The Manobo bee-hunting song is the manganinay, and the prehunting songs are the panlalawag, tiwa, and udag-udagu. The Ibanag vendors’s song is the cansion para allaku. The Aeta fishing song is the magwitwit; their hunting song is the aget. One Cebuano working song is also a love song:

Ako ang manananggot

Sa lubi kanunay’ng nagsaka;

Giyamiran sa mga babae,

Kay pulos ako kono mansa.

Kubalon ako’g samput,

Adlaw ug gab-i sa lubi nagsaka

Apan hinlo nga walay sagbut

Kining ako, Inday, nga gugma.

(I am a tuba gatherer

Who climbs coconut trees every day.

Women frown upon me

Because I am full of stains they say.

The skin around my loins has thickened,

For day and night I climb coconut trees;

But pure and spotless

Is my love for you, Inday.)

Work and activity songs express the feelings, longings, and outlook on life of the Filipino worker. Some songs are joyful celebrations of short happy breaks from toil. Such is the case with drinking songs, sung in times of merrymaking. These are a special type of social song, and seem to come mostly from the Bicol region, where they are called tigsik, and the Visayan islands, where they are called dayhuan. Most of them are short songs, sung with cheerful abandon and the spirit of camaraderie. In the southern Tagalog region, the women and men take part in these happy occasions as they drink their native wine. Typical and popular in the Visayas is the song “Dandansoy,” which is about the drinking of sweet, inebriating tuba, fermented coconut toddy. This has different versions in Cebu, Bohol, and Leyte, and is not to be confused with the “Dandansoy” earlier discussed.

An activity song from Antique is performed during the biray, a ceremony held in first week of May to ask the Santo Niño for rain. Two groups representing Muslims and Christians ride boats in a procession on the river. The flags held by each boat are entwined at the end of the ritual, signifying unity and peace (Villareal 1997, 80-81).

The Blaan sing a song in order to remember their tasks. Here is “Lamge,” which means “to work” (Eugenio 1996, 578):

Lamge ha, lamha, wadu, wonde gende

Wukelo genha fambo ha wakelatun ha wadu

Wadene mande wagene han akeba han ha hubal

yo han ha wadene manande holonka yonha nangat

hu kong bende wukilak gengen ha wanulu han

aladju man ha ogumup gonindi undigo

han alonga fon ha hay ha!

(What we do? Oh, what can we do

This is our work, this we should do.

Oh my, how, oh, how is this to go on?

Continue, then come back when you reach the top.

’Tis not there! ’Tis not here! they said.

We’ll try till we can make it.

It’s not here, according to them, but don’t relax.

Don’t be surprised. They’re still far.

Let’s hurry!)

The Sama Dilaut of Tawi-Tawi have several occupational songs. Fishermen sing the kalangan bailu or “songs of the wind” during sailing trips, particularly at night while they patiently wait for the catch. A lonesome singer often sings the kalangan bailu in a melancholy tone; sometimes a fisherman sings to a companion in a nearby boat. The kalangan kalitan or “shark songs” are sung when Sama Dilaut fisherfolk hunt for sharks. The song often flatters the shark, enticing the animal to take the bait. When boys or grown men hunt a certain variety of crustacean for food, they sing the kalangan kamun. “Kamun” is the Sama word for the sea mantis, which is known for its flavor (Nimmo 2001, 194-96).

There are songs that describe drunkards. One song in Bicol depicts them as drinking until they collapse on the bench. In a Waray song, a man drinks glass after glass and finds himself sprawled on the street the following morning. In olden times, drinking feasts celebrated individual, family, or community milestones: exploits in war, successful harvests or hunts, new clearings, or weddings.

Religious festival songs commemorate various feasts that are observed by the people throughout the annual cycle or to mark various stages of the life cycle. The Cebuano harito is a prayer for blessings.

The babaylan of Panay have various types of chanted prayers: the ambaamba is a thanksgiving prayer for blessings received; the pahagbay is a ritual offering to Andungon, god of infants; the batak-dungan is a prayer that a newborn be granted intelligence and a sense of respect for its elders; the unong is an entreaty to an offended nature spirit to restore the health of the offender, who is being punished with an illness; the bugyaw is an exorcism chant; the tara is a pre-housebuilding prayer chant; the riring is a harvest prayer; the dag-unan is an annual ritual invoking a good planting and harvest season.

Among the Kalinga, the tubag is a prayer to tribal spirits to grant a child prosperity and protection from disease. Bontok old men sing the ayyeng during a cañao to pray to Lumawig for strength. The Bukidnon sing the kaligaon during religious ceremonies. The Bagobo gindaya is a hymn in praise of competition during the gin-em festival. The Aeta sing the magablon to call upon the spirit Limatakdig to cure the sick. Another Aeta ritual song for the sick is the kagun. Many Subanon songs are sung as prayer, one of which is the semba, a praise song that has been infused with Christian elements (Aleo et al. 2002, 263-71). The Tiruray siasid is a prayer to god Lagey Lengkuwas and the nature spirits.

Christmas songs are the Isinay kantan si dubiral, Ilonggo daygon, Cebuano dayegon or daigon, Ibanag aguinaldo, and the Pangasinan aligando (the longest carol in the Philippines) and its shorter version, the galikin. Among the best-known carols in the lowlands is “Ang Pasko Ay Sumapit” (Christmas Is Here), whose melody originally came from a Cebuano song titled “Ka Sadya ning Taknang” (What a Happy Occasion). One of the earliest daygon is “Daygon sa Noche Buena,” which is composed of verses with specific parts sung to praise God, or to greet the residents of the house (Villareal 1997, 192-23).

|

| Cebuano elders performing dayegon or Christmas songs, 1991 (CCP Collection) |

Other songs are usually sung in May, which is the month of flowers and of the Blessed Virgin Mary. In Batangas, rituals of floral offerings to Mary are held in little bamboo chapels during this month, accompanied by the singing of “Pag-aalay kay Maria” (Offering to Mary). On the night of All Saints’s Day, “souls” go from house to house asking for alms from the living, requesting them to please hurry because the gates of heaven might be closed shut before they make it back there. The carolers sing “Kaluluwa Kaming Tambing” (We Are Ghosts) as they go along, and it used to be that niggardly people, having refused to give alms, would sometimes discover the loss of their fowl kept under the house. Songs are also sung during the feast days of patron saints, such as San Jose on 1 May and San Isidro on 15 May.

Miscellaneous songs cover a wide range of themes: friendship, welcome, farewell, humor, nature, and others. Chants for special occasions are called dawot by the Mandaya, oggayam by the Isneg, dayomti by the Ikalahan, and salidummay by the Bontok. The Kalinga ading, dango, and oggayam are songs for expressing feelings related to the occasion, such as peace-pact celebrations and weddings. The Ifugao wedding song is the chua-ay. The Ikalahan baliw is an extemporaneous chant for funerals or weddings. The Bontok fallukay is a boastful song for head-hunting victory celebrations. The kumintang is the Tagalog war or battle song, while the sambotani is the victory song.

Songs about friendship and conviviality are sung during social visits. Thus, most of these are songs of welcome and farewell. In Marinduque, visitors are welcomed in a ritual called putungan (crowning), in which they are crowned with a wreath of flowers, and songs in praise of their coming are sung. The Western Bontok song “Salidummay,” which greets visitors, can also be a farewell song, sung by the men to the young women as they bid goodbye to one another after a wedding or some other festive occasion.

The Ilocano have a special song for a birthday celebrant, which they sing while crowning the celebrant with flowers. The birthday song may well be the universal social song in the Philippines, except that the version most commonly used is American—that is, “Happy Birthday,” with the Tagalog adaptation, “Maligayang Bati.”

In the Maranao song “Dayo Dayo Kupita” (My Friend, My Friend, It Is Morning), a friend invites another to visit the river. The Koran is invoked to dispel a fear of snakes and crocodiles (Eugenio 1996, 481).

Humorous songs express a rather childlike sense of wonderment and joy at strange things and happenings. Some songs sound like typical tall tales. A flea yields nine jars of lard. A woman cooks fire in a paper pot, using water as fuel. A song tells of a crab so big it takes seven people to lift just its claw; another wants us to believe that there is a yarn bigger than the Rizal monument.

A way to address illicit subjects is through humorous songs. In Panay and Negros, one finds “Si Lusong Kag si Hal-o” (Mortar and Pestle), a jocular harvest song that uses imagery from nature to suggest the sex act (Villareal 1997, 85-86).

Subtle humor is found in songs satirizing human frailties and foibles. A man says that he will settle for a dark-skinned girl because she is not choosy about food. In another song, a man is rejected by a beautiful girl because he is cross-eyed, and so he vows to look for a spinster, who would be willing to overlook his physical impairment. Nonsensical songs can be whimsical, funny, or absurd. An old Tagalog favorite is “Lalaking Matapang” (Brave Man):

Ako’y ibigin mo

Lalaking matapang

Ang sundang ko’y pito

Ang baril ko’y siyam

Ang lalakarin ko

Parte ng dinulang

Isang pinggang pansit

Ang aking kalaban.

(Love me

I’m a brave man

Seven daggers have I

I also have nine guns

I’m taking a journey

On part of a low table

A plate of Chinese noodles

Is the enemy I’ll be fighting.)

The American period saw the transformation of folk song into what is known today as “pop” or “popular music.” Mass media, developments in technology, and the emergence of urban spaces influenced the modern iteration of folk music as well as the concept of ownership. In contrast to folk songs of the past, the folk songs now are identified with particular singers or composers; conversely, materials already “owned” by other artists can now be more easily recycled or repurposed (Fong 2011, 98).

One curious outcome is the distinctly hybrid form of Ibaloy pop songs, which are folk songs that appropriated American “country” music. The Igorot’s embrace of the cowboy persona sprung from early encounters with American colonialists. Before the Americans established Baguio City as a key settlement, they brought horses to the mountains, hired Igorot guides, and introduced country music to the locals. As it happened, the Igorot and the American cowboy were not unlikely cultural counterparts. Both valued fortitude, industry, and independence (Fong 2011, 84-87). The Americans sold the cowboy lifestyle through cinema and radio. The Igorot began to wear saddle boots and cowboy hats, and sang songs about their experiences in the manner of American country music (87). Thus, the Ibaloy pop song came to be.

These songs were first performed in sadaan or community dances, and eventually were recorded in studios. Rodolfo “Rod” Danggol is considered a pioneering artist. Other prominent figures include Eufornio Pungayan (Morr Tadeo), Acheng Kilaban, June Jaime, Randy Osting Balag-ey, Roy Tad-o Basatan, and Josefa Botangen Ognayon, the only woman with an all-Ibaloy album titled Baley Shima Shontog (Fong 2011, 125). Addressing a wide audience that included Filipino and foreign tourists, these musicians performed songs in Ibaloy, Kankanaey, Ilocano, Tagalog, and English.

Several Ibaloy and Kankanaey pop songs are either lyrical or melodic reworking of Ilocano, Tagalog, and English originals (Fong 2011, 100-131). Turbaan or debates in song were performed to the tune of “Clementine.” Kilaban composed “Ihay-anak” (New Born) using the melody of “Amazing Grace.” “Layad Nan Likatan” (The Love We Have Suffered), a Bontok song by Pedro Chinalpan, which inspired Danggol, was sung in the melody of John Hugh McNaughton’s “When There’s Love at Home” (100). This method is comparable to that of Alfredo “Fred” Panopio of Nueva Ecija. An actor and singer, Panopio acted in films but became widely known as a singer who has a signature yodeling style. His song “Ang Kawawang Cowboy” (Poor Cowboy), about a lowly “cowboy” who has a gun but no bullets, is set to the tune of Larry Weiss’s “Rhinestone Cowboy.”

If not modified versions of American country songs, Ibaloy pop songs are original compositions sung during weddings, concerts, and in taverns called “folk houses.” They are played on commercial discs, aired in local radio stations, stored in portable hard drives, and uploaded on YouTube. The Ibaloy pop artist sings about love, the hardships of life as musicians, and historical events such as World War II, Cordillera regionalization, and the earthquake of 1990, among others (172).

The 1960s and 1970s saw the revival of protest music that began in agrarian and labor movements of the 1930s (Rodell 2002, 184). Though mass media was heavily suppressed, professional musicians wrote songs containing social commentary (Cabangon and Jimeno 2008), changing the course of mainstream Filipino music. Student protesters revived Jose Corazon de Jesus’s kundiman “Bayan Ko” (My Country) to decry the abuses of Ferdinand Marcos’s militia. APO Hiking Society’s tender but patriotic “Hindi Ka Nag-iisa” (You Are Not Alone) became a popular protest song after the assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr in 1983 (Rodell 2002, 185). At the 1986 EDSA Revolt, protesters once again sang “Bayan Ko.”

The commercial music industry found a renewed sense of dignity when protest music, which endorsed love for country, rose to popularity among listeners (Rodell 2002, 186). Songs about love in the time of social unrest, war-torn hometowns, and a crumbling society were set to percussive, guitar-laden rock and roll sound, the genre of protest music in the United States during the 1960s and the Vietnam War (Candaele 2012). Local artists had been losing out to foreign acts in album sales until Pinoy folk rock caught the sentiments and imagination of listeners. In contrast, musicians categorized as the “Manila Sound”—Hotdog, Cinderella, and VST & Company—composed cheerful, pleasant songs (Rodell 2002, 186).

The Juan de la Cruz Band’s “Ang Himig Natin” (Our Hymn) is considered the first Pinoy folk rock song (Rodell 2002, 186). “Ang Himig Natin” invites the listeners to sing “our song” in the course of finding hope at a lonely hour. Anak Bayan, Asin, Banyuhay ni Heber, Coritha, Florante, Freddie Aguilar, Gary Granada, Judas, Maria Cafra, and Sampaguita followed the lead and became prominent Filipino folk rock musicians. One of their recurring themes is the search for identity.

|

Cassette cover of songs by Gary Granada (Vicor Music Corporation and Gary Granada)

|

Florante’s “Ako’y Isang Pinoy” (I Am a Filipino), a song that quotes Jose Rizal, confronts the issue of using one’s own mother tongue. Mike Hanopol, a former member of Juan de la Cruz Band, wrote “Awiting Pilipino” (Filipino Song), which describes a search for identity and laments the loss of the “Filipino song,” appealing to listeners to return to their roots and help revive what was once a rich tradition.

“Tayo’y mga Pinoy” (We Are Filipinos) by Banyuhay ni Heber directly addresses the inferiority that Filipinos feel toward Americans, whose more prominent proboscis is perceived as both cosmetic boon and social status. Gary Granada takes a milder approach to address social issues. In “Kahit Konti” (Even a Little), Granada promotes calm dialogue among people with contrary viewpoints.

There are also songs that scrutinize the individual’s responsibility for the decline of society. “Batugan” (Idler) by Judas calls out the lazy and apathetic who do not pull their own weight. “Dukha” (Poor), also by Judas, describes a hand-to-mouth existence, an experience with which many Filipinos during the Marcos regime could identify. Hanopol’s “Laki sa Layaw” (Spoiled Brat) satirizes the upper-class man who cannot find happiness in spite of his power and wealth, until his self-destructive behavior lands him in jail.

Asin’s songs are remarkable for their haunting melodies and environmental and sociopolitical themes. “Masdan Mo ang Kapaligiran” (Look Around You) urges listeners to open their eyes to the degradation of the environment. “Pagbabalik” (The Return) is about a person longing to return to her homeland, an anthem for Filipinos who had to work overseas. “Himig ng Pag-ibig” (Song of Love) tells of a woman waiting for the return of a loved one. “Tuldok” (Dot) ruminates how the existence of human beings seems puny in the vastness of space.

|

| Album cover of songs by Asin (Vicor Music Corporation and Gary Granada) |

Particularly poignant are songs by Asin about the civil war in Mindanao. “Ang Balita” (The News) speaks of a “promised land” (lupang ipinangako) that is streaked with blood. The last lines of the song shift to Cebuano, echoing the call for others to listen to the story of the singer’s hometown. “Ang Bayan Kong Sinilangan” (My Hometown) refers to the province of South Cotabato, in which people, supposedly related by blood, are fighting because of differences in religious and political beliefs.

“Tatsulok” (Triangle) by the activist folk rock band Buklod speaks of reversing the “triangle” of inequality in a society under military rule (Remollino 2007).

Freddie Aguilar’s “Anak” (Child), an entry in the Metro Manila Popular Music Festival in 1977, is a ballad about a child who, wanting to be free, ends up taking the wrong path in life. Aguilar merges Western musical influences with the folk tradition, particularly the pasyon (Rodell 2002, 186), as noted by Felipe de Leon Jr. Aguilar’s song has since been translated in 27 languages, a testament to its universal appeal.

In the 1980s, Bukidnon-born Joey Ayala and his band Bagong Lumad composed music that featured indigenous musical instruments, such as the hegalong, the kulintang, and the kubing, along with Western instruments such as the electric guitar and drums.

Ayala’s songs often criticize the materialism of modern living, the neglect of the environment, and the loss of cultural identity. His first album, Panganay ng Umaga (Morning’s Firstborn), which was released in 1981, includes the somber “Wala Nang Tao sa Sta. Filomena” (There Is No One in Sta. Filomena), a song about a farming community whose residents are ominously missing. In “Karaniwang Tao” (Ordinary People), Ayala sings about the layman who stands defenseless in the wake of environmental destruction wrought by industries. “Ania Na” (Here It Comes) denounces illegal logging and grabbing of land from local inhabitants. “Magkaugnay” (Connected) describes national unity among many tribes. Ayala has become an influential figure to Mindanao-born folk musicians such as Bayang Barrios of Bunawan, Agusan del Sur, and Davao’s Gauss Obenza, Geejay Arriola, and Maan Chua, all of whom are members of the Mebuyan Peace Project.

In 2014, a young musician from Palo, Leyte, received acclaim for his folk-inspired acoustic music (Sallan 2014). A nod to Ayala’s influence, “Ninuno” (Ancestor) by Bullet Dumas calls on the youth to save the environment from deterioration, an act akin to honoring their predecessors.

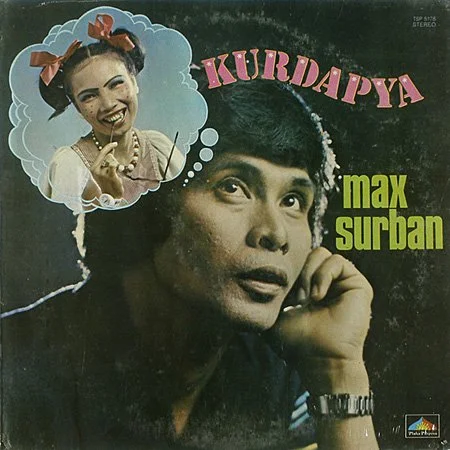

Between the 1970s and the 2000s, musicians also composed lighthearted and humorous folk-influenced songs. The Boholano singer Yoyoy Villame and the Cebuano Max Surban became household names for their original compositions and adaptations. Villame and Surban were both admired for their populist brand of humor and sensibility.

|

| Album cover of song collections with folk influences by Max Surban, 1975 (Sunshine) |

Like the Pinoy folk-rock bands, Villame first became popular in the late 1970s. Although his most memorable songs are “Mag-Exercise Tayo Tuwing Umaga” (Let’s Exercise Every Morning) and “Butsekik,” composed of amusing gibberish, it is history and nation that are Villame’s most frequent themes (Gallardo 2007, 28). “Philippine Geography” is a catchy song that enumerates the names of the towns from Luzon to Mindanao. In “My Country, Philippines,” Villame extolls the islands’s natural beauty. In “Magellan,” Villame recounts the origin of Filipino Catholicism and the battle between Ferdinand Magellan and Lapulapu. After he gets wounded, Magellan calls for his mother, “Oh mother, mother, I am sick! Call the doctor very quick!”

Comparable to Villame in popularity, Max Surban produced around 33 albums from 1976 to 2014 (MaxSurban.net). “Gihidlaw na Intawon Ako (Mitulo Na)” (I Miss You So) is a bilingual tune that has roots in Visayan folk songs about heartbreak and longing. Surban sang local versions of foreign songs and added a humorous quality to them. Set to the tune of Dean Martin’s “Sway,” “Kinse Ra” (Just Fifteen) is about a man who has had 15 wives.

Surban also performed Visayan folk songs such as “Turagsoy” and the Cebuano version of the Tausug “Baleleng.” Other songs, like “Gahi Dako Taas” (Hard Big Long), use double entendres. Women want love that is “hard,” “big,” and “long.” “Ang Manok ni San Pedro” (San Pedro’s Chicken) encapsulates Surban’s style of setting an irreverent folktale to music. A gambler named Esteban goes to heaven and meets Saint Peter at the gate. However, Peter tells Esteban that his death was a mistake and that he must return to earth. As consolation, Saint Peter gives him a white rooster. Back on earth, Esteban wins big in the cockpit, thanks to the gift from Saint Peter.

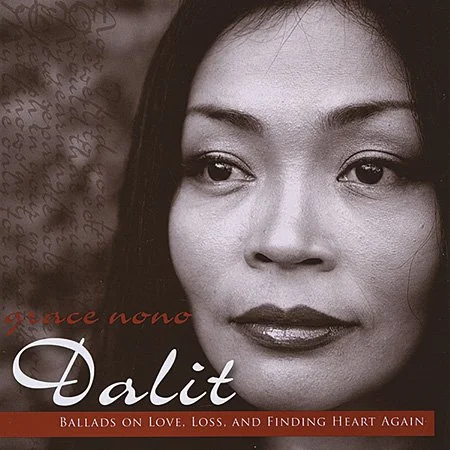

From the 1990s to the 2000s, musicians made use of academic scholarship and advancements in recording technology to revitalize traditional Filipino music. In 1993, ethnomusicologist and singer Grace Nono produced her acclaimed album Tao Music. The album’s carrier single “Salidumay” is Nono’s reworking of the Kalinga harvest song. In 1995, Opo was released, showcasing Nono’s technique of combining various folk traditions. The album included Nono’s rendition of “Dandansoy”; “Buntag Na” (It’s Morning Time), a Cebuano song with a melody adapted from Tboli music; and “Yayewan,” a song with Tagalog lyrics and a chorus adapted from an Iraya swaying song. “Yayewan” also shows Nono’s experimental approach: a verse in the song is a translated excerpt of a Duwamish chief’s message to the US president in 1852 ("Grace Nono" 2002).

In 2002, Nono produced Diwa, a compilation of praise songs adapted from Tagalog, Ilonggo, Itawit, Ibanag, and Kalinga traditions. In 2009, Nono reinterpreted Visayan folk songs in her album Dalit: Songs of Love, Loss, and Finding Heart Again. The songs “Sala Ba Diay ang Gugma?” (Is Love a Sin?), “Kamingaw sa Payag” (Loneliness in the Hut), and “Kung Imo Akong Talikdan” (If You Turn Away from Me) were among the 10 love songs in the album.

|

| Album cover of song collections with folk influences by Grace Nono, 2010 (Tao Music) |

At present, the folk song lives on through former Buklod member Noel Cabangon, Gary Granada, Bayang Barrios (Cabangon and Jimeno 2008), and through Visayan musicians such as Cebu’s Enchi, Junior Kilat, The Ambassadors, Missing Filemon, and Leyte’s Groupies Panciteria.

The legacy of Max Surban and Yoyoy Villame has been passed on to Rommel Tuico, whose song “Dili Tanan” (Not All) impishly reminds listeners through a laundry list of items that appearances may mislead, from election voters, fashion victims, to gender performance.

Popular Cebuano music, regardless of genre, has been influenced by the folk tradition. Junior Kilat’s “Original Sigbin” describes a beast from Visayan folklore. The Ambassadors’s “Ulipon sa Gugmang Giatay” (Slave of Damned Love) is a Cebuano love song embraced by a new generation of listeners. Enchi’s “Dili Lalim” (Unmaginable) speaks out against animal cruelty.

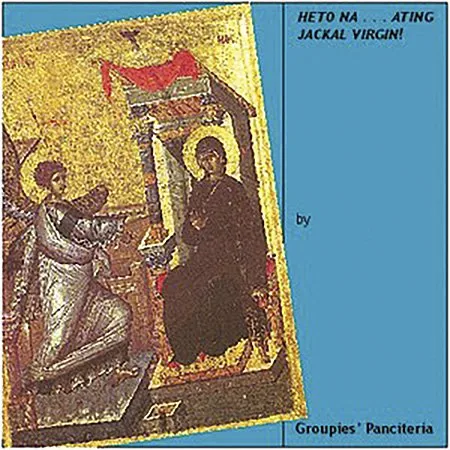

In 2009, Tacloban-based Groupies’ Panciteria released, through the audio-sharing website SoundClick, “Heto Na … Ating Jackal Virgin! (Here It Is … Our Jackal Virgin). The album contains 14 politically charged songs, in the manner of Gary Granada, Juan de la Cruz Band, and Yano, and which can be both appreciated by regular folks who frequent neighborhood eateries; hence, the use of the word panciteria (noodle place). The songs cover various genres, from ska, rock, to rap music, but contain subjects rooted in social realities, such as the call center lifestyle, national elections, and the failed promises of government officials (Groupies’ Panciteria 2009).

|

Album cover of song collections with folk influences by Groupies Panciteria, 2005 (Bananakyu Repablik)

|

“Binola, Ni-Rape, Minarder (The Apparition, sa Katolikong Bansa ng Ating Jackal Virgin)” (Fooled, Raped, Murdered [The Apparition, in the Catholic Country of Our Jackal Virgin]) is about the gruesome assault of a bar dancer whose body is later found by the river. “Cebuano Indios Attack at Dawn Magellan’s Estero” is a commentary on the Cebuano tourism industry. “This Is My Blood (Waray Waltz)” describes the drinking session of locals in an impoverished Waray town (Groupies’ Panciteria 2009).

In 2013, the Artists and Musicians Marketing Cooperative (Artist Ko) held a songwriting contest promoting Cebuano popular music (Taguchi 2013). The songs that came out of the Visayan Pop Songwriting Campaign eventually became hits in Cebuano radio stations, the video-sharing platform YouTube, and the audio-streaming companies such as Spotify and SoundCloud.

One of the most recognized VisPop (Visayan pop) songs is Jewel Villaflores’s grand prize winner “Duyog” (Accompaniment). The song’s lyricism is influenced by contemporary Cebuano poetry. Another VisPop song is the playful “Papictura Ko Nimu, Gwapo” (Let Me Have a Photo with You, Handsome) by Marie Maureen Salvaleon. The male is the object of affection by the female as she asks for a picture with him, which she plans to upload to social network sites. Lourdes May Maglinte’s “Laylay” (Lullaby) has the quality of a nursing song, but it can also be sung as a love song. Another VisPop radio hit is Marianne Dungog and Kyle Wong’s “Balay ni Mayang” (Mayang’s House). “Balay ni Mayang” features the conversation of male and female singers. The woman is inviting the man to visit her at her house. These modern pop songs sound like traditional folk songs: “Balay ni Miyang” recalls the balitaw, and “Papictura Ko Nimo, Gwapo,” the humorous courtship song.

In the age of the Internet, many traditional songs are shared on various platforms, particularly on YouTube, making them accessible not only to those who are in the communities from which songs are created, but also to listeners from different parts of the Philippines and in other countries. In turn, the Internet has widened the audience of the folk song and extended its chances of surviving.

One example is the Sama Dilaut pakiring pakiring, which is popularly known as the song “Dayang Dayang.” “Dayang Dayang” first became a hit nationwide when it was played on the radio in the late 1990s. Pariking pakiring refers to the dance movements, but “Dayang Dayang” became the title of the song in its commercialized form (Jubilado 2010, 99). Today, the song has various versions and remixes on YouTube, with most of the videos showing Tausug and Badjao dancers performing the pakiring pakiring. As of 2015, the video titled “Dayang Dayang (Original Version),” which was posted on 30 July 2007, has reached over four million views. No one knows the identity of the female voice behind the popular recorded version, but the song continues to gain listeners from all over the world.

1 comment:

Thank you for the research and beautiful examples!

Got Something to Say? Thoughts? Additional Information?